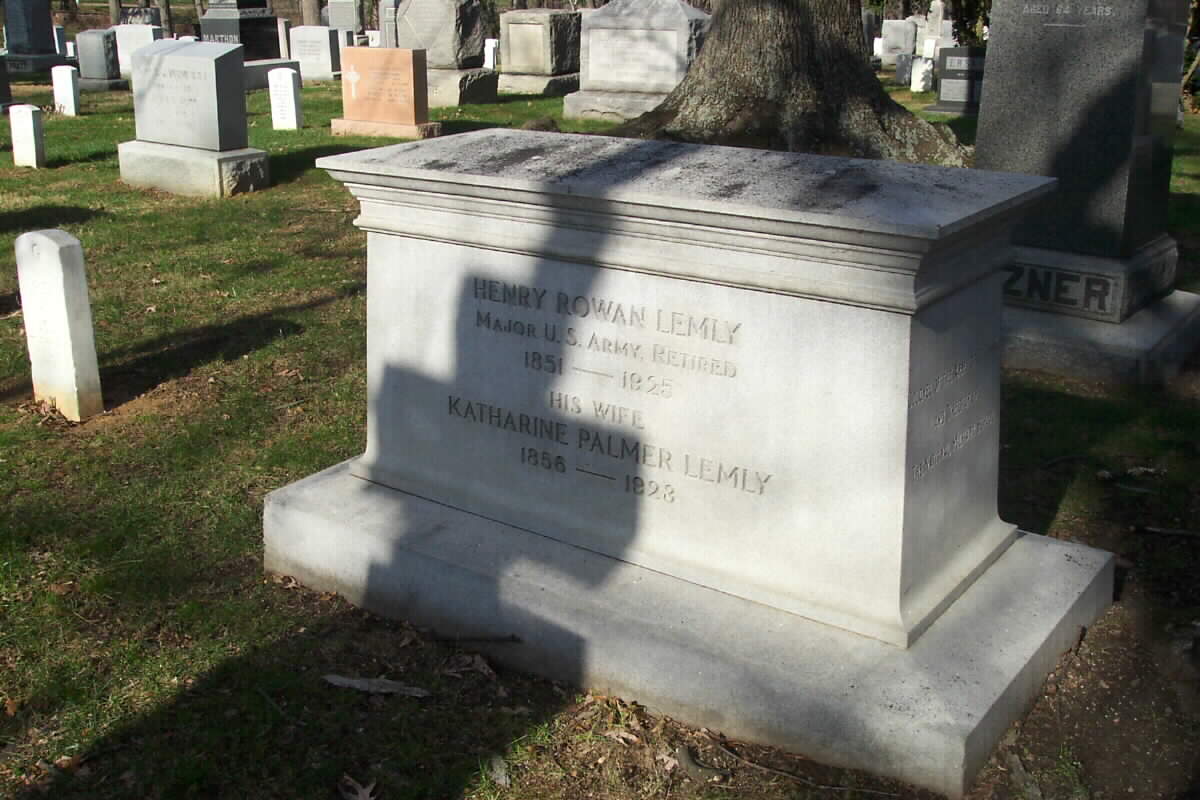

Courtesy of John D. Mackintosh

Henry Rowan Lemly was born in Bethania on January 12, 1851, the son of Henry Augustus Lemly and Amanda Conrad Lemly. The elder Lemly was a native of Rowan County who had attended the University of North Carolina in hopes of becoming a doctor. Poor eyesight spelled an end to that dream though and he went on to become a merchant in Salisbury before moving to what became Forsyth County.

In 1868, the year of North Carolina’s readmission to the Union, young Henry sought and received a coveted appointment to the United States Military Academy through the influence of his Republican uncle, I.G. Lash, who was elected to Congress in the autumn of 1868 just after his nephew had entered West Point.

Lemly’s entrance to the Academy was as part of the first class containing young men from the former Confederate states. For Lemly and his fellow Southern cadets, such as South Carolinian George D. Wallace, West Point was attractive since it offered free education at a time when the South was economically hard pressed due to the loss of the war. Four long years of the Spartan lifestyle of a cadet ensued, with Lemly graduating on June 14, 1872, finishing a very respectable eleventh in a class of fifty-seven.

Following a period of brief graduation leave in which he returned home to North Carolina, Lemly was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Third Cavalry and joined Company E of his regiment at Fort Sanders, Wyoming Territory on October 1.

Over the next three years he moved between posts in southern Wyoming and Nebraska, becoming acclimated to the sense of separation from the rest of the nation that characterized life in the frontier army. Apparently, conditions weren’t entirely agreeable with him, as he journeyed home on sick leave in December 1875 and returned in May of the following year, just days before the departure of the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition.

The Grant administration had been trying to follow a peace policy in its relations with the Sioux and Cheyenne of the Northern Plains but the increasing pressure of settlers and gold seekers trying to get into the Black Hills, combined with retaliatory raids from the Sioux against settlements, resulted in the demand that all free roaming Indians not on reservations report to one by January 31, 1876, an unrealistic deadline that had passed without full compliance. The expedition that Lemly joined thus sought out the adherents of the nomadic plains way of life, such as the bands of warriors who accompanied leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Surprisingly, considering his time away from the regiment, Lemly was appointed battalion adjutant for the Third Cavalry’s ten companies that were part of the large military force under General George Crook.

The Third Cavalry battalion left Fort D.A. Russell on May 21, heading north for a union with the rest of Crook’s command as they made their way north towards the Sioux.

June 9, 1876 witnessed the young lieutenant’s baptism of fire, as elements of Crook’s Third Cavalry had a brief, virtually bloodless skirmish with Sioux Indians who had occupied bluffs above the Tongue River in northern Wyoming. On June 17, the expedition had just entered Montana Territory, resting peacefully along the banks of Rosebud Creek in the morning sun. Just two days later, Lemly somehow found the time to write down a fresh account of what he barely lived through: “we were suddenly surprised by the sound of shots from in front and the whistling bullets falling in our midst.(7) Over a thousand Sioux and Cheyenne warriors, many under the leadership of Crazy Horse, had broken the early morning respite of the tired soldiers, very nearly overrunning their position before defensive measures were taken. Lemly ended up on the left flank of the action under Colonel William Royall. The situation worsened as “our entire line was now under fire from the Sioux, who occupied the highest ridge in our front but shot rather wildly…nothing had been accomplished by our repeated charges except to drive the Sioux from one crest to immediately reappear upon the next. Casualties occurred among them, of course, as with us, but beyond the indefinite equalization, nothing tangible seemed to be gained by prolonging the contest. When we took a crest, no especial advantage accrued by occupying it, and the Sioux ponies always outdistanced our grain-fed American horses in the race for next one.

As nothing was being gained, the battalion began to move towards the right, seeking to rejoin the main body of Crook’s command. This movement was not without its consequences though, as “the Sioux appeared to construe it as a retreat and doubtless believed that they had inflicted a severe loss upon us. From every ridge, rock and sagebrush, they poured a galling fire upon the retiring battalion…our casualties, comparatively light until now, were quickly quadrupled.

As the danger increased, Colonel Royall sent Lemly with a message to Crook to send forth infantry companies to help cover the movement. At one point, the North Carolinian had his horse shot out from under him but came away unscathed by the incident. Newspaper reporter John F. Finerty then witnessed yet another narrow escape for fortunate officer: “Lieutenant Lemly came near losing his scalp by riding close up to a party of hostile Indians whom he supposed were Crows. His escape was simply miraculous.

After some six hours of fighting, the action ended with the Sioux and Cheyenne departing the battlefield. Crook and his men soon left as well, returning towards their encampment near the Big Horn Mountains in Wyoming. Lemly alluded to the criticism General Crook was receiving from men up and down the ranks: “It is not my business to criticize. His enemies say that he was outgeneraled. That his success was incomplete, must be admitted, but his timely caution may have prevented a greater catastrophe. When he penned those words, Custer’s Last Stand was only five days away and would result in the death of America’s most celebrated Indian fighter, killed by many of the same Sioux and Cheyenne that had bested Crook. Lemly’s musings on a “great catastrophe” therefore seem prophetic.

The North Carolina lieutenant was involved in much of the remainder of the Great Sioux War, including the long and trying “mud march” of Crooks forces that finally bore fruit with the September victory of the army at Slim Buttes in what is now South Dakota. Apparently, he did not leave behind an account of that battle, possibly because he entered the engagement as it neared its end. By the Spring of 1877, the bands that had defeated Crook and Custer had either been driven into Canada under Sitting Bull or were reluctantly surrendering. To many, the May capitulation of Crazy Horse at Camp Robinson, Nebraska represented a symbolic end to a war that had reached its dramatic pinnacle at the Little Big Horn. At the time of Crazy Horse’s surrender, Lemly was stationed at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, probably the most famous post of the frontier military West.

The continuing presence of Crazy Horse’s band, camped at nearby Camp Robinson was accompanied by rising tensions, even though the Sioux leader had vowed that his warrior days were over. Various factions among the Sioux were jealous of his power and sought to raise fears among the military that he was not a peaceful man. Once again, Lemly took to the field as part of a Third Cavalry battalion, sent to the Camp Robinson area, and left a record of all that transpired: “The column of cavalry was directed to so time its arrival, after a night march, that it could surround the village of Crazy Horse at daybreak….when they arrived upon the bluffs supposed to overlook the village there were no tepees in sight. The bird had flown!

The military high command had intended on capturing Crazy Horse and sending him east for imprisonment at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. Eventually, Crazy Horse was talked into once again returning to Camp Robinson. The events that followed were carried out under the command of General Luther P. Bradley and Captain Jesse M. Lee, both of whom Lemly defended by stating “no more honorable officers ever lived….and the part they played inadvertently or by compulsion that day was no doubt revolting in the extreme. Somebody high up had blundered, but orders had to be obeyed.

Lemly was serving as officer of the guard and in command of Troop E of his regiment on the fatal day of September 5, 1877. He was thus in close proximity to all that transpired in the crowded parade ground area of Camp Robinson as plans unfolded to lock Crazy Horse in the guard-house, prior to transporting him east. Just days after the event, Lemly’s anonymous report of what happened appeared in the New York Sun of September 14, 1877:

Taking Crazy Horse by the hand, Captain [James] Kennington led him unresistingly from the adjutant’s office into the guardhouse, followed by Little Big Man, [who] now became his chief’s worst enemy. The door of the prison room was reached in safety, when, discovering his fate in the barred grating of the high windows, the liberty-loving savage suddenly planted his hands against the upright casing, and with great force thrust himself back among the guards, whose gleaming bayonets instantly turned against him. With great dexterity he drew a concealed knife from the folds of his blanket, and snatched another from the belt of Little Big Man, turning them upon Captain Kennington, who drew his sword and would have run him through but for another Indian who interposed. Crazy Horse had advanced recklessly through the presented steel, the soldiers fearing to fire, and gaining the entrance he made a leap to gain the open air. But he was grappled by Little Big Man.

A struggle between the powerful Little Big Man and Crazy Horse followed, with the knife accidentally piercing Crazy Horse “who sank in a doubled-up posture upon the ground outside the door.”

Writing of this event in 1914, Lemly revised the cause of the great warrior’s death: “Crazy Horse gained the door of the building and, with another leap, fell upon the ground outside, pierced through the groin and abdomen by the bayonet of one of the guard.

This cause of death is in conformity with the generally accepted view of most historians as to how Crazy Horse died. The earlier account differed from this since, as Lemly recalled in 1914, it was “unofficially sought to be conveyed; but while I did not actually see the stroke, the conversation by members of the guard, which I overheard, convinced me that Crazy Horse was killed by a thrust from a bayonet.” There then followed an occurrence every bit as harrowing as the Rosebud battle, when, “as if with a single click, thirty carbines were cocked and aimed at us by as many mounted Indians, who had formed a semi-circle around the entrance to the guard-house. Fortunately for all concerned, the soldiers were able to diffuse the situation, partially by assuring the Sioux that Crazy Horse was “ill” since most had not actually seen what proved to be the fatal bayonet thrust. Later, they spread the story that he had accidentally stabbed himself, a deception echoed by Lemly in his newspaper article. In the aftermath of the stabbing, Lemly was in charge of the dying prisoner and could only watch as the efforts of Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy proved futile in saving his life. The tragic occurrence ended with death of Crazy Horse in the adjutant’s office, when, “in a weak and tremulous voice, he broke into the weird and now famous Sioux death-song.

For Lemly, the demise of Crazy Horse came near the end of his participation in the frontier military. The following year, he was transferred to the artillery, a branch of service that was rarely posted in the West since it primarily staffed coastal fortifications. In 1880, he was promoted to first lieutenant just before receiving a congressionally approved leave of absence to accept a teaching position at the National Military School in Bogota, Colombia. He returned to the United States three years later and continued serving at various artillery posts before, once again, returning to Colombia in 1890. In the later part of that decade, he was promoted to captain on the eve of the war with Spain. Unlike the Sioux War, he saw no action in that conflict but instead served as an aide-de-camp to Major-General Guy V. Henry, who had been severely wounded in the Rosebud battle the two men had lived through some twenty-three years before. In 1899, he retired in Washington, D.C., just over thirty years after entering West Point. Retirement proved anything but idle as he continued to work with the Colombian military as well as represent various armament manufacturers in Europe and Asia. With the American entry into World War I in 1917, he briefly returned to duty with the Quartermaster Department, which resulted in his promotion to major prior to his full retirement in 1920.

Somewhere in the midst of this busy career, he met and married Katharine Palmer, daughter of Major General Innis Newton Palmer. Together, the couple had two children, Major Rowan P. Lemly and Mrs. Katharine Parker. He also found time to author numerous books, including various military training manuals in Spanish, as well as a biography of Simon Bolivar that was published in 1923.

He never forgot his service in the 1870s, when he both experienced danger and witnessed history. He joined the Order of the Indian Wars, an organization of Indian War veterans dedicated to preserving the memory of those who had fought and served in the West. He also worked with Indian Wars history researcher Walter M. Camp in marking the forgotten graves of those who had perished in Great Sioux War. On October 12, 1925, preceded in death by his wife, he passed away in Washington, D.C., at a time and place far removed from the vast open prairies where he had faithfully served as a young Lieutenant.

NOTE: His son, Rowan Parker Lemly, Colonel, United States Army, and his wife are also buried in this plot in Arlington National Cemetery.

LEMLY, HENRY R

- MAJOR US ARMY RET

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/12/1925

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SECTION 1 SITE 99-D

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

LEMLY, KATHERINE PALMER W/O LEMLY, HENRY R

- DATE OF DEATH: 12/31/1923

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SECTION 1 SITE 99-D

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

- WIFE OF HR LEMLY, MAJOR US ARMY RET

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard