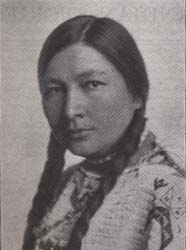

Raymond T. Bonnin and Miss Gertrude Simmons, both of Yankton Agency, were married at the home of Mr. and Mrs. E. H. Benedict in this city on Saturday afternoon, May 10, 1902.

The Tribune is pleased to make a few comments upon this marriage from the fact that the bride is a full blooded Sioux whose Indian name is ”Zitkala-Sa,“ which means Red Bird.

After receiving a common school education at Yankton Agenoy she was sent to Carlisle College, where she remained two years and where she developed great musical and literary talents to such an extent that she was sent to the Boston Conservatory of Music and was selected to accompany a musical troupe to the Paris exposition in 1900.

The rare talent show both on the violin and piano brought forth many flattering comments from the leading maga zines and newspapers, both at home and abroad. Upon her return she made a tour of the prindple cities of the East, not only as an accomplished musician but as an author of esteemed merit. One of her productions entitled “Indian Legends” has commended itself to the reading public to the extent that the publishers are having a great demand for her works. She is also a contributor to some of the leading magazines at the present time.

The groom is the grandson of the old French trader, Picotte, one of the first traders to oome up the Missouri River to Yankton Agency and points above and into who married one of the Yankton Sioux Tribe. His family were all educated at the Standing Rock Reservation, South of St. Louis and they and their children are among the foremost of the Yankton tribe in civilized at &inmenta. This is considered a marriage in high life among their people, as both of the contracting parties are proud of their aboriginal blood, and especially of their rapid acquirement of the educational skill of the Caucasian race so rapidly adopted by them. Her Indian friends may well feel proud, without being egotistical, at the marvelous advancement made of a full-blood of their race who left her native home encumbered with that legacy of native habits and who within a few short years mastered the English language to the extent that she rivals in literature some of the leading authors of America, and whose quaint productions are equal to those of Kipling.

Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, Zitkala Sha (Red Bird), was an extraordinarily talented and educated Native American woman who struggled and triumphed in a time when severe prejudice prevailed toward Native American culture and women. Her talents and contributions in the worlds of literature, music, and politics challenge long-standing beliefs in the white man’s culture as good, and Native Americans as sinful savages. Bonnin aimed at creating understanding between the dominant white and Native American cultures. As a woman of mixed white and Native American ancestry, she embodied the need for the two cultures to live cooperatively within the same body of land. Her works criticized dogma, and her life as a Native American woman was dedicated against the evils of oppression.

Bonnin was born in 1876, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Her father was a white man named Felker, about whom little is known. Her mother was Ellen Tate Iyohinwin (She Reaches for the Wind) Simmons, a full-blooded Sioux. Bonnin was Simmons’ third child. At only eight years of age, Bonnin decided to leave her mother and the reservation to attend White’s Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Indiana. This was a school funded by the Quakers. After four years she returned home, but then enrolled, against her mother’s wishes, at the Santee Normal Training School. She chose this school because it was close to her mother. In 1895, she decided to move on and accepted entrance and scholarships to Earlham College in Indiana.

Though most noted for her literary and political genius, Bonnin was an accomplished violinist and even won a scholarship to study at the Boston Conservatory of Music. In 1913, she and classical music composer William Hanson wrote an opera called Sun Dance. The creation was appreciated by a few Native Americans, but since 1937 has gone unnoticed. Neither before nor since has there been an opera written by a Native American. Music was Bonnin’s real love, yet she felt it more important to fight for the rights of her people through literature and politics.

After her studies at the Boston Conservatory, Bonnin accepted a teaching position at the Carlisle Indian School. The school was founded by Richard Henry Pratt, an army officer who saw education as a means to move “from savagery to civilization” and believed that “We must kill the savage to save the man.” Pratt abusively exploited the students for labor while at the same time receiving government funds for each student attending the school. Bonnin’s stay at Carlisle Indian School lasted two years.

As a writer, she adopted the pen name “Zitkala Sha” and in 1900 began publishing articles criticizing the Carlisle Indian School. She resented the degradation students underwent, from forced Christianity to severe punishment for speaking in native languages. She was criticized for this because many felt she showed no gratitude for the kindness and support that white people had given her in her education.

Bonnin had two marriage proposals in her life. The first was made by Carlos Montzuma, a Yavapai activist and physician. She broke this engagement off because her own plans for her life extended beyond his hopes for her to be his helper and mother of his children. The second proposal, which she accepted, was from Captain Raymond Bonnin. He was a mixed blood Nakota living on the reservation and working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Unfortunately, the marriage did indeed prove detrimental to her career as she was forced to follow her husband’s career as they moved from reservation to reservation. The Bonnins had one son named Ohiya (Winner).

On a reservation in Utah the Bonnins became part of the Society of American Indians, of which she was elected secretary in 1916. The Bonnins moved to Washington, D.C., where Gertrude continued her work with the Society and began editing the American Indian Magazine.

A strong political voice for Native Americans, Bonnin wrote Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft, Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes, Legalized Robbery. This work, published in 1924, with two white co-authors, exposed the robberies and murders in Oklahoma of Native American people and led to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, reestablishing a trust for Indian lands. Bonnin was also pivotal in gaining the rights of citizenship and the vote for Native Americans. She did this by seeking unity between all tribes in a pan-Indian political power. Thus began the National Counsel of American Indians, in 1926.

Bonnin died in 1938, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Her tombstone is marked “Zitkala-Sa of the Sioux Nation,” and is also inscribed with a picture of a tipi. Ironically, the burial honor was due not to her great contributions to the U.S., but because of her husband’s position as an Army Captain.

Of her literary works, Bonnin’s “Why I Am a Pagan” perhaps best explains her religious beliefs. It was first published in the Atlantic in December of 1902, a time society was accustomed to and expectant of Native American essays about conformations to Christianity. Coupled with a chapter – “The Big Red Apples” – from Impressions of an Indian Childhood, Bonnin’s case is made against traditional and religious Christianity. The two works are fascinating and the dynamic they form expresses the indignations suffered by the Native Americans at the hands of Christians.

Bonnin was ardently against the oppression of the Native Americans in Western culture, though she saw it as an intimate part of the language of the “pale-faces.” Bonnin cleverly alludes to the Biblical story of Adam and Eve’s fall as a metaphor for the seduction of the Native Americans by whites in “The Big Red Apples.” Eve was seduced by the snake because of her ambition for knowledge. Bonnin created a parallel to her own childhood experience of the “pale-faces” from the East coming to her reservation looking for Indian children to recruit for their school. The men from the East seductively promised “Yes, little girl, the nice red apples are for those who pick them” in the East (Lauter 928). So against her mother’s wishes, Bonnin ate from the forbidden tree and headed east.

Bonnin’s masterful use of language and her grasp on Western allusions add to the effectiveness of her writing. Like many other minority writers, she learned about the culture oppressing her and developed writing techniques so her voice could be at least heard and hopefully understood by the dominant culture. Had Bonnin used allusions to Native American stories and her native language, she would have not affected her target audience, the oppressive “pale-faces.”

Bonnin’s “The Big Red Apples” causes white readers to re-think traditional Christian conquests by suggesting that the Indian was corrupted by the dominant culture. “Why I Am a Pagan” further challenges a reverent and religious Christian to see the beauty of Indian beliefs, and their love of nature, appreciation of the wonder for the universe, and acceptance of all (even the “pale-face”) as being part of God’s creation. The image of a God-fearing, accepting, and loving being is a sharp contrast to the image of a savage warrior.

In “Why I am a Pagan,” Bonnin worshipped a God that created the beauty in the world and a religion that embraced “a kinship to any and all parts of this vast universe” (Lauter 938). Bonnin contrasted this with the Christianity to which her cousin subscribed, that “taught me (him) also the folly of our old beliefs” (Lauter 939).

God did not call the white man to destroy a beautiful Native American culture, nor steal their homelands, nor pen them up on reservations, or even to beat Indian children for speaking their mother tongue. Though she resented this mistreatment, Bonnin still aimed at bridging a gap between the vast differences of the dominant white and the Native American cultures. She did not let her self be seduced into believing that her Native American traditions were folly, or sin. As a person of mixed blood, her life could be looked upon as an example of the beauty and accomplishments that can be made when the two cultures can live cooperatively. Bonnin realized that to hate difference was to hate life; Bonnin was a lover of life. Perhaps it is time that the U.S. had a national cemetery to honor those like Bonnin who sought peace and loved life, rather than hail those adept at killing it.

Gertrude Simmons Bonnin (1875-1938)

Zitkala-sa, “Red Bird,”a Yankton Sioux reformer and writer was one of a number of White-educated Indians who fought to obtain fairer treatment for her people by the federal government. She was born on February 22, 1875, the daughter of John Haysting Simmons and Ellen Tate’Iyohiwin, “Reaches for the Wind.” Educated on the reservation until the age of 8, she was sent to White’s Institute, a Quaker school in Wabash, Indiana. At the age of 19, against her family’s wishes, she enrolled at Earlham College, in Richmond, where she won an oratorical contest, then graduated to become a teacher at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

She wanted to become a professional writer but was also interested in music. In following this latter interest, she studied at the Boston Conservatory and went to Paris in 1900 as a chaperone and leader with the Carlisle Band. She became an excellent violinist and enjoyed playing the instrument as a hobby. She also composed an Indian opera based upon the Plains Sun Dance. Harper’s published tow of her stories at the turn of the century, and three of her autobiographical essays appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. In 1901, her first book, Old Indian Legends, appeared and received a cordial reception.

By this time, Zitkala-sa was back on the reservation, where in 1902 she married a Sioux employee of the U.S. Indian Service, Raymond T. Bonnin; they had one male child. That same year the couple moved to the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in Utah, where they lived for the next 14 years, and where she worked as a teacher for the Indian Service. In 1911 she became active in the Society of American Indians, an organization of educated Native Americans dedicated to the improvement of the conditions of their people. The group was basically interested in the integration and assimilation of the Indian, favoring equal rights for all people, and strongly opposed to the continuance of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In 1916, when she was the society’s secretary, the Bonnins moved to Washington, D.C. She lobbied for her people among the vari0us officials in the Capitol, and also helped persuade the General Federation of Women’s Clubs to take an active interest in Indian welfare. Roberta Campbell Lawson, a part-Delaware woman from Oklahoma was also prominent in the club’s hierarchy at this time, and the two women worked together closely.

Under pressure from the Women’s Clubs and others, the federal government agreed to the appointment of a commission to investigate the Indian situation. In 1928, this group, of which Gertrude Bonnin was an advisor, turned in its noted Report, under the supervision of Lewis Meriam. The following year President Hoover appointed two Indian Rights Association leaders to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Administration took even more significant steps to reform United States Indian policy.

In 1926, Zitkala-sa founded the Council of American Indians, and continued to work tirelessly for the rights and welfare of Indians until her death in Washington January 25, 1938 at the age of 61. She was buried in Arlington Cemetery.

January 2005:

Dear Sir,

I am currently researching a paper on the life of the Indian writer and activist Zitkala-Sa, also known as Gertrude Bonnin. I understand that due to her husband’s military service she was buried in Arlington Cemetery. I am trying to locate either a picture of her headstone and its location (i.e. is it next to Capt. Bonnin?) or a copy of the inscription on it.

I would be so grateful if you provide some answers for me! As I am studying in England, it can be quite hard to know which channels to go through to get this kind of information. I do hope that you are able to help me.

I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Kind Regards and many thanks in advance

Emma Kuntze

BONNIN, GERTRUDE SIMMONS

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/28/1938

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 01/28/1938

- BURIED AT: SECTION E2 SITE 4703

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY - Wife of RT BONNIN, CAPTAIN, USA

BONNIN, RAYMOND T

- Captain, United States Army

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 08/14/1917 – 08/18/1919

- DATE OF DEATH: 09/24/1942

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 09/26/1942

- BURIED AT: SECTION E2 SITE 4703

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard