Congress has created a memorial fund for

the families of the two slain U.S. Capitol Police officers.

Donations may be sent to the

U.S. Capitol Police Memorial Fund,

Washington, D.C. 20510.

Click Here For Photographic Coverage

Weston’s Mental State Outlined In Court: April 1999

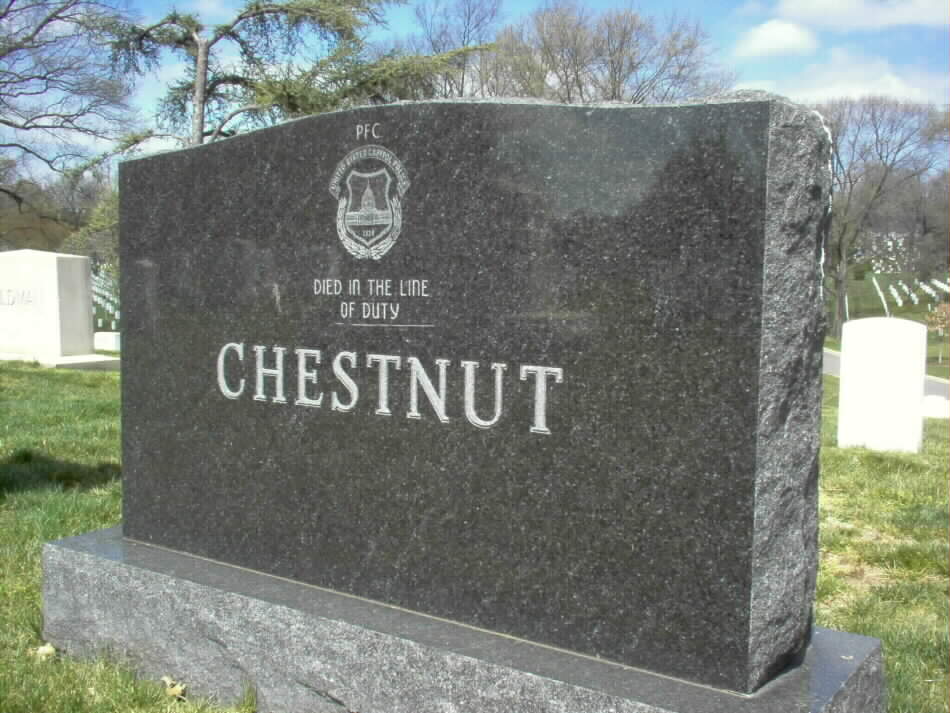

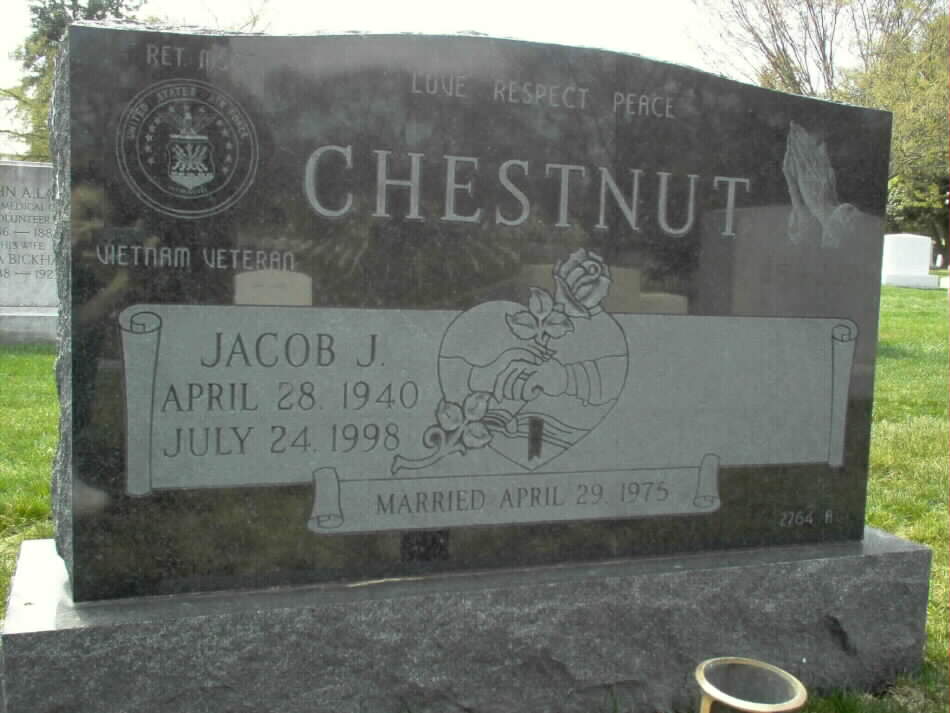

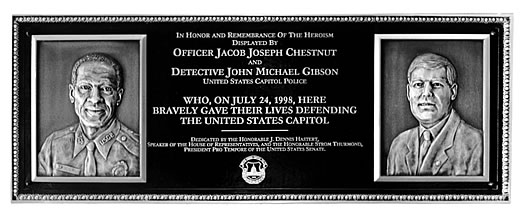

Jacob Joseph Chestnut

John Michael Gibson

United States Capitol Police Officers

Murder Charges Filed in Capitol Rampage

Sunday, July 26, 1998

Russell Eugene Weston Jr., a former mental patient from Montana, was charged yesterday with murdering two U.S. Capitol Police officers during a rampage in the Capitol building that allegedly began when Weston walked up behind an officer and shot him point-blank in the back of the head.

Law enforcement sources and court documents added chilling new details yesterday about the Friday afternoon killings of Jacob J. Chestnut, 58, and John M. Gibson, 42, both 18-year veterans of the force. They said that after bursting through a Capitol security checkpoint and shooting Chestnut, Weston chased a screaming woman down a hallway until he was confronted by Gibson, who pushed the woman out of harm’s way and exchanged deadly gunfire with the intruder.

Weston, 41, slipped into unconsciousness and was downgraded early yesterday from stable to critical condition after surgery Friday at D.C. General Hospital. Doctors said he had a “50-50” chance of survival. He was ordered held without bond yesterday during a brief hearing in D.C. Superior Court.

An FBI agent’s affidavit filed in court says Gibson and another officer — identified by law enforcement sources as Douglas B. McMillan — fired at Weston several times. Angela Dickerson, a 24-year-old employee of a Virginia furniture store, was wounded by stray gunfire. She was released yesterday from George Washington University Medical Center.

Meanwhile, official Washington paused yesterday to pay tribute to the pair of officers who died in service to their government, as the nation’s leaders vowed that the domed symbol of American democracy would remain open and accessible to the public. The Capitol did reopen yesterday, with flags at half staff and the Capitol Police force guarding the doors as usual.

“I want to emphasize that this building is the keystone of freedom, that it is open to the people because it is the people’s building,” said House Speaker Newt Gingrich. “No terrorist, no deranged person, no act of violence will block us from preserving our freedom and keeping this building open to people from all over the world.”

President Clinton yesterday praised the two men as heroes who “laid down their lives for their friends, their co-workers and their fellow citizens,” and he reminded the country that 79 other law enforcement officers have been killed this year. “Every American should be grateful to them for the freedom and the security they guard with their lives,” Clinton said.

Friday’s incident has brought new attention to the tricky security balance between ensuring public access and protecting public officials, and several members of Congress said it demonstrated the need for a long-delayed $125 million visitor’s center that could help security officers control access to the Capitol complex.

But most observers agreed there was little the Capitol Police could have done to stop a determined and apparently deranged gunman like Weston, who had complained to neighbors in Rimini, Mont., that the government was using a satellite dish to spy on him. He once accused his frail 86-year-old landlady of assault and battery, and allegedly harassed several county and state officials when they refused to press charges against her.

Weston spent the last several years in the Montana backwoods, living on disability benefits in a cabin 40 miles from the tiny shack where the reclusive Theodore Kaczynski built his bombs. In early 1996, law enforcement sources said, he was interviewed by the Secret Service about unusual comments he had made about President Clinton and delusional letters he had written about the federal government.

Weston was entered into the Secret Service’s computer files as a potential low-level threat, but the agency did not contact other law enforcement agencies about Weston and had no further contact with him, the sources said. “The volume of people that the Secret Service checks out and never comes into contact with again is just unbelievable,” one law enforcement official said.

In the fall of 1996, Montana officials said, a judge committed Weston to a state mental hospital for evaluation after he threatened a Helena resident. He was released after 52 days, when a medical team concluded that he no longer posed a danger. But on Thursday, after he reportedly shot his father’s cats, he allegedly stole his father’s old Smith & Wesson revolver and pointed his red Chevrolet pickup truck toward Washington.

In Valmeyer, Ill., the riverside town where Weston grew up, the Rev. Robin Keating read a statement from Weston’s family yesterday apologizing profusely for the deaths of the officers. “It is with great sorrow that we speak today — sorrow for the families that lost their loved ones, sorrow for the children that lost their daddies,” the statement says. “Our apologies to the nation as a whole, for the trauma our son has caused.”

An affidavit signed by FBI Special Agent Armin Showalter and filed in D.C. Superior Court yesterday recaps the horrifying moments after Weston allegedly walked into the Document Room Door on the House side of the Capitol at 3:40 p.m. Friday. Law enforcement sources said security videotapes that captured some of the incident provide vivid images of the grisly scene.

Chestnut was standing with his back toward a metal detector, writing some directions for a father and son who had just finished a tour of the Capitol, according to one law enforcement source who watched the videotape.

Weston allegedly walked through the detector, setting it off, then immediately pointed his gun at the back of Chestnut’s head and shot before the officer had a chance to take action. Chestnut collapsed in front of the tourist and his 15-year-old son, who was soaked in the fallen officer’s blood, according to the source.

“He was shot without warning,” said Sgt. Dan Nichols, a Capitol Police spokesman.

As congressional aides and tourists scrambled for cover, Officer McMillan fired back at Weston, authorities said. Dickerson, a visitor who was standing nearby, was shot in the face and shoulder by a stray bullet, but officials said they have not determined who shot her.

“I don’t really consider myself a hero,” said McMillan, who was working near Chestnut’s station Friday and said he witnessed his killing. He declined further comment.

Weston ran past them, following an unidentified female bystander who was running for cover toward a door that reads “Private Entrance” leading to the majority whip’s suite. Inside, Gibson yelled for DeLay and his staff to take cover under desks and other furniture. DeLay yesterday said he and several staff members hid in his private bathroom and locked the door.

Before Gibson was able to draw his gun, the woman, with Weston behind her, appeared in the doorway. Gibson “pushed her away to safety,” and Weston shot him once in the chest, Nichols said. Gibson then grabbed his own gun and shot Weston in the legs.

While the two men fired more shots at each other — one witness said there were at least eight or 10 rounds — the woman scrambled frantically in the hallway from closed door to closed door, pleading for someone to help her. Witnesses told police they heard her yelling, “Help! Help! Help!” but they were too afraid to open doors for her, sources said. Moments later, more Capitol Police officers arrived on the scene and arrested Weston, who had “additional ammunition” for his six-shot revolver in his pocket, according to the FBI affidavit.

“It was just a mess,” one police source said. “Chestnut was executed, and Gibson saved everybody’s lives in that office. If it wasn’t for his fast thinking, I’d hate to think of what could have happened in that office.”

A visibly moved DeLay met with reporters yesterday, recalling Chestnut as “a great man and a great patriot” and Gibson as “quite simply the finest man I’ve ever known.” He said Chestnut, a father of five and a grandfather of five, was a Vietnam veteran who greeted everyone with a smile. He said Gibson, a Massachusetts native and Boston Bruins fan who worked as his personal security detail, had become a virtual member of his family.

“He tried to teach me hockey,” DeLay said, his voice breaking. “I never did understand hockey.”

Weston, who received CPR from Sen. Bill Frist (R-Tenn.) and a D.C. paramedic shortly after the incident, has undergone surgery twice for gunshot wounds to the torso, buttocks and legs, and his surgeon, Paul Oriaifo, said he has a “50-50” chance of survival. Neither Weston nor the slain officers was wearing a bulletproof vest, law enforcement sources said.

Authorities charged Weston under a federal statute that covers cases in which federal law enforcement officers are slain during performance of their official duties. The case will be moved on Monday from the local court to federal court, which was closed yesterday. Attorney General Janet Reno has the option of seeking the death penalty, but a Justice Department spokeswoman said discussions of the question have not yet begun.

The last federal execution took place in 1963, although more than a dozen federal prisoners are on death row, including Timothy J. McVeigh, who was convicted in the April 1995 bombing of a federal office building in Oklahoma City. Prosecutors have been especially reluctant to seek the death penalty for federal offenses in the District, where voters overwhelmingly rejected a local version of the law in a 1992 referendum.

The Capitol Police force has worked almost round-the-clock on the investigation, along with officers from the FBI, D.C. police and other law enforcement agencies. The arrest warrant for Weston was signed at 2 a.m. yesterday, and federal agents executed a search warrant for Weston’s shack yesterday afternoon. Other agents have been interviewing neighbors and family members in Illinois and Montana and more than 80 witnesses in Washington.

It has been a horrible two days for the 1,295-member Capitol force, which had had only one other casualty in its 170-year history, an accidental shooting death during a 1984 training exercise. A visibly exhausted Nichols said yesterday at a news conference that officers are taking solace in the support they have received from the public, and in the fact that they succeeded in protecting the members of Congress.

“It’s been a trying couple of days for us,” Nichols said as he choked back tears. “It’s a difficult time, and the officers are going to rely on each other. . . . But the gunman didn’t get very far into the building, and that was our intention.”

Funerals for the officers have not been scheduled, but DeLay said members of Congress hope to honor them with a joint resolution tomorrow and a memorial service on Tuesday. Congress also has created a memorial fund for the families of the slain officers, and donations can be sent to the U.S. Capitol Police Memorial Fund, Washington, D.C. 20510.

Nichols also said the Capitol Police had received many requests from visitors wanting to know if they could leave flowers on the House steps in honor of the fallen officers.

They certainly could, he said. And yesterday, they did.

U.S. Leaders Honor Officers

Tuesday, July 28, 1998

In mournful tribute beneath the Capitol dome, President Clinton praised two slain police officers Tuesday as heroes whose sacrifice “consecrated this house of freedom.” Lawmakers and thousands of visitors joined in a daylong outpouring of sympathy.

Jacob J. Chestnut and John Gibson, killed last Friday by a Capitol intruder, “died in duty to the very freedom that all of us cherish,” said House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

The widows, children and other relatives of the slain men were seated for the memorial service, a few feet from the flag-draped coffins bearing the remains of their loved ones. All others in attendance stood.

Customarily, only presidents, members of Congress and military commanders are permitted to lie in the Rotunda. Congress made an exception in the case of the two fallen officers, and by early morning, hundreds of people were in line outside the Capitol waiting to pay their respects.

Some wept, some saluted, others simply stared at the caskets as the long line filed slowly up the Capitol steps and into the soaring Rotunda where the coffins rested. An honor guard, four Capitol Police officers in dress blue uniforms, stood somber watch.

Joining the mourners were delegations of law enforcement officials from across the nation.

Chestnut and Gibson were shot Friday afternoon when a gunman burst into the Capitol with a .38-caliber handgun. Chestnut was shot without warning, according to an account provided by officials, while Gibson and the gunman both fell following a furious exchange of gunfire at close range.

The suspect, Russell E. Weston Jr., 41, of Rimini, Mont., underwent surgery during the day for irrigation of his fractures. Hospital said he was in stable condition.

Weston, who has a history of mental illness, has been charged with one count of killing federal officers, and faces a possible death penalty if convicted.

A federal magistrate postponed Weston’s initial appearance in court until Thursday in the hope that he will be well enough to make the trip then.

The memorial service was unprecedented — the nation’s political leadership gathered in one of the most hallowed rooms in the land to mourn not a president or a general, but two men unknown outside their own communities.

Standing in a room graced with images of George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and other famous Americans, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott said, “Today we honor two men that should rightly be recognized in this hall of heroes. … It’s appropriate today that we honor these two men who did their job, who stood the ground and defended freedom.”

In his remarks at the brief ceremony, Clinton paid tribute to the “quiet courage and uncommon bravery” exhibited by Chestnut, Gibson and so many other police officers who are struck down in the line of duty.

The two men killed last Friday, he said: “in doing their duty they saved lives, they consecrated this house of freedom and they fulfilled our Lord’s definition of a good life. They loved justice, they did mercy, now and forever, they walk humbly with their God.”

For the second straight day, the House canceled its legislative business out of respect for the two men who died while at their posts in the Capitol.

“In our hearts and in our minds, their heroism can never be forgotten,” said Rep. Lynn Woolsey, D-Calif., one of several lawmakers to speak of the two men in the House during the day.

“Who could ever imagine a shooting in the nation’s Capitol, a shrine to liberty and justice for all,” added Rep. Constance Morella, R-Md.

Across the Capitol, Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, R-Colo., pinned a Capitol policeman’s patch to his jacket — a gift, he said, from Gibson a few weeks ago.

The Rotunda was closed to the public for a while at midday to permit members of Congress to view the caskets. Gingrich, Democratic leader Dick Gephardt and House GOP Whip Tom DeLay, his wife and daughter formed a receiving line for fellow lawmakers. Gibson had served as DeLay’s bodyguard.

The scene in the Capitol’s Rotunda was unprecedented as powerful lawmakers and tourists alike came to pay their respects to Chestnut and Gibson.

First inside were Jeffrey Barrow, 13, and his father, Don, a locksmith from Atlanta, who had been in the Capitol Friday when the shooting broke out.

“I wanted to come and pay respects,” said the boy. “I’ve been asking myself why would he want to kill them. They didn’t do anything to him.”

Many uniformed police officers also filed past, some of them wiping away tears, as the long, hot day wore on.

Chestnut, who was 58, and Gibson, 42, will be buried later in the week at Arlington National Cemetery.

Slain Officers’ Coffins to Lie in Capitol

Monday, July 27, 1998

The bodies of U.S. Capitol Police officers Jacob J. Chestnut and John M. Gibson will lie tomorrow in the majestic Rotunda of the building where they gave their lives, a farewell usually reserved for the nation’s revered leaders.

The two policemen slain Friday will lie at the Capitol Rotunda throughout the day, an unprecedented honor for the men who died defending tourists and elected representatives. The public will be admitted to pay tribute to the officers from 8 a.m. until 7 p.m., except for a brief period beginning at 3 p.m. when members of the Capitol Police, the officers’ families and Congress will attend a private ceremony. President Clinton and Vice President Gore also plan to attend.

Yesterday, the private and public families shattered by the violence struggled slowly to deal with the aftermath of Friday’s violence. Also yesterday, U.S. Capitol Police Chief Gary L. Abrecht offered his first public comments; authorities continued to search for clues to the suspect’s possible motive; and visitors to the Capitol placed still more flowers on the steps as an expression of their grief.

Meanwhile, Russell Eugene Weston Jr., 41, charged with killing the two officers when he burst into the Capitol on a languid Friday afternoon, was upgraded from critical condition to serious condition by officials at D.C. General Hospital.

Weston, a drifter with unusual suspicions, barged through a metal detector Friday and allegedly executed Chestnut, 58, without warning, and then killed Gibson, 42, in a gunfight.

Law enforcement sources said yesterday that Weston emptied his six-chamber .38-caliber Smith & Wesson pistol; in return, he was wounded in the torso, arms, buttocks and thigh.

Weston is under arrest, held without bond on two federal murder charges, as he lies under heavy guard in the locked ward of the hospital. Charges against him, filed Saturday in D.C. Superior Court, likely will be transferred today to U.S. District Court. The federal court was closed on Saturday, so prosecutors secured an order in D.C. Superior Court to keep Weston in custody.

Law enforcement sources said the prosecution team already is bracing for a possible insanity defense or claim of incompetency, as new details emerged of Weston’s behavioral history, including a 1996 visit by Weston to Central Intelligence Agency headquarters in which he claimed he was a clone and President John F. Kennedy’s son.

Congress is expected to reconvene today with a tribute to the officers. Both houses are to approve the public viewing of the officers’ caskets in the Rotunda, an honor until now afforded only 27 people in the nation’s history. Four were unknown soldiers; all the others were presidents, generals, members of Congress or other dignitaries.

Separate funerals for the men are set for Thursday and Friday, each including a motorcade past the Capitol.

“My thoughts and prayers go out to the families,” said Abrecht, who has met privately with the families. “They were in a great state of grief.”

The police chief said Gibson will be buried on Thursday in Lake Ridge. Chestnut, an Air Force veteran, will be interred the following day at Arlington National Cemetery.

Abrecht said his review of the incident convinced him “our people did exactly what they should have done. They were heroic in every way.” Abrecht, speaking later at a brief news conference outside the Capitol, called his two officers “fallen heroes” and said he could not comprehend how their families were dealing with their deaths with such grace.

Abrecht recounted how, after the shootings, his own teenage daughter “came running up to me and threw her arms around me” in a scene he thought was being repeated in police families all across the nation.

“The past few days have been an extremely trying time for the United States Capitol Police,” Abrecht said. “From the expressions of sympathy which have been pouring in to our department, it is evident that our loss and feelings of sadness are being shared by the United States Congress and the American public.”

In a separate interview, Abrecht recalled that he would often “stop and chat with Chestnut; he was a wonderful, quiet professional police officer. He was steady and unruffleable.” Abrecht said Chestnut had a “friendly but firm manner. He was excellent with the public.”

Jonathan L. Arden, chief medical examiner of the District, said yesterday that autopsies of the two officers Friday night showed that “neither one of them had any significant chance of being able to survive his wounds.”

“Unfortunately, there are some wounds that simply are not survivable,” Arden said. He said Chestnut died of a gunshot wound to the head that penetrated the brain, and Gibson died from a wound to the abdomen with penetration of his aorta.

It is unclear whether Chestnut ever confronted his killer. According to law enforcement sources who have watched a security camera videotape, Chestnut was standing with his back to the metal detector, writing directions for a father and son, when Weston strode through the metal detector and immediately shot Chestnut in the back of the head.

Tourist Angela Dickerson, 24, who was escorting relatives on a Capitol tour Friday, also suffered gunshot wounds during the incident. She was discharged from the hospital Saturday.

A note saying “No Soliciting Please!” was taped to the front door of Dickerson’s family home in Chantilly yesterday. Knocks at the door and calls to the home went unanswered.

Liz Lapham, 44, a neighbor who said she had spoken to Dickerson’s father, said that he told her his daughter was “going to be okay. She’s just really exhausted and resting,” Lapham said. Dickerson, an interior designer, has been married for a year, Lapham said.

“It’s really a tragedy that she was where she was,” Lapham said. “They’re overwhelmed by it.”

Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies continued to study Weston’s life, seeking to understand what may have driven a man considered a harmless nut by neighbors in Illinois and Montana to such bloodshed.

Several hundred law enforcement officers are now working on the case in Illinois, Montana and Washington. Sources said they have executed search warrants at his parents’ home in Valmeyer, Ill., and his shack in Rimini, Mont., an old mining community about 20 miles southwest of the state capital of Helena. They popped open the door to his mountain shack with a crowbar attached to a cable and sent in a remote-control robot to protect themselves from any possible booby traps. None was found.

They also found magazines and a stack of papers with Weston’s diaries and other writings in the red Chevrolet pickup truck the suspect drove from Valmeyer to Washington on Thursday night, the sources said.

A top-ranking law enforcement source said agents searching the home of Weston’s parents in Illinois were looking for writings in a sealed container that might show motive or premeditation.

Weston had come to official notice several times. Citing state laws protecting the confidentiality of medical records, an official at the Montana State Hospital in Warm Springs declined to discuss the specifics of Weston’s treatment at the psychiatric facility during a 53-day stay in late 1996. A court ordered what is known as an involuntary civil commitment for Weston because of repeated threats against Jefferson County law enforcement authorities stemming from a dispute he had with his elderly landlady in 1983.

Weston was discharged from the state hospital on Dec. 2, 1996, and arrangements were made to allow him to prepare his cabin in Rimini for winter and then return to the supervision of his parents in Waterloo, Ill.

In an interview yesterday at their home, Weston’s parents said their son was diagnosed a decade ago as a paranoid schizophrenic.

“I don’t know what you can do about someone like that,” a source at a federal agency said. “If the doctors thought he was okay, how can anyone else predict he’ll go off?”

Law enforcement sources also were studing the details of Weston’s visit on July 29, 1996, to the Langley headquarters of the CIA.

According to a source familiar with a memorandum on the incident, Weston drove up to the main CIA gate off Route 123 and said he had information to report. The source said Weston “rambled on for several hours” to a security officer, explaining that he was the son of Kennedy, that he had been cloned at birth, that Clinton was a clone, that everyone was a clone. He also claimed that Clinton was responsible for the Kennedy assassination because Kennedy had stolen Clinton’s girlfriend, Marilyn Monroe.

“He was clearly delusional, but he didn’t make any threats,” the source said. “If he had, we would have arrested him. But it was just, ‘I’m a clone, Clinton’s a clone, all God’s children are clones.’ He told a bunch of wild stories and drove off into the sunset.”

Weston, who has told his neighbors he believes the government is watching him through satellite dishes, also told the security officer he received “special presidential programming through interactive television and radio.”

Weston ended his visit by informing the officer that he would “report back in 10 or 15 years.” He later sent two letters to the CIA.

The first letter, which was typed, informed the agency that “as timing reverse becomes more aphonic,” he thought he should join the CIA. The second letter, which was handwritten and sent in May, complained that someone had stolen a time device that he had invented. It was signed: “Brigidier General Russell E. Weston.”

Weston’s previous actions could present difficulties for government prosecutors, who have charged him with two counts of murdering federal officers in the performance of their duties, charges that could carry the death penalty.

If Weston’s attorneys question his competency to stand trial, a judge would have to find that he understands the nature of the proceedings and can assist in his own defense before the prosecution could proceed.

If Weston goes to trial, his attorneys might employ an insanity defense – that is, argue that he was not sane at the time of the attack and therefore did not know the wrongfulness of his actions.

“I know that if I were Weston’s lawyer, I’d be thinking about an insanity defense,” one law enforcement official said. “Clearly, it looks like that’s what we’re up against. … But there’s a big difference between ‘crazy’ in the vernacular and ‘crazy’ in the legal sense.”

Weston’s past activities and his alleged involvement in the Capitol shootings also have raised anew questions about how federal agencies determine what they consider dangerous behavior, and what they can do about it.

The Secret Service had a routine interview with Weston in the spring of 1996, after learning about comments and letters he had written about Clinton and the federal government. But the agency classified him as a “low-level threat” and did not notify other agencies, although it did keep his name on file. The CIA source said his agency briefed the Secret Service again after Weston’s visit to Langley, but neither agency took any action.

“Obviously, this guy has problems, but lots of people have problems,” one federal law enforcement source said yesterday. “Everyone has a constitutional right to be crazy.”

The CIA official also said his agency’s options were limited in dealing with a delusional but non-threatening individual: “It’s not unusual to have strange people show up at our gate. We treat it seriously, but there’s only so much you can do if laws aren’t broken.”

In their investigation of Friday’s fatal gun battle, authorities have interviewed more than 80 witnesses in Washington, and believe more than 20 of them will be able to help them reconstruct the crime in court, sources said. They said authorities also plan to interview John Broder, a New York Times reporter who said he was approached by a man resembling Weston in Lafayette Square the morning of the shootings. According to the Times, the man pointed at the White House and said: “Millions of people are going to die because of the people you put in that house.”

As authorities concentrated on the official investigation of the shootings, many people seemed drawn to the scene of the crime to leave their own personal tributes.

On the marble Capitol steps, a makeshift shrine of flowers and bouquets grew through the day, even as sightseers returned to wait in line for a tour of the Capitol.

A child-drawn picture with the note “Peace on Earth” addressed a message to the officers: “Thank you for being there and protecting so many.”

Jeanne Gross, 68, came from Germantown with her friend Genevieve Dunbar, 74, to deliver flowers to the Capitol because “it’s sad that they have to give up their lives for someone so demented. They have wives, children, left alone.”

Barbara Rackle, 55, of Gaithersburg, said, “I had to come. This is our heritage,” pointing toward the American flag that whipped, in the stiff breeze, at half-staff above the Capitol. “Our liberty is so costly. Things like this do happen, but I just couldn’t believe it would happen here, in our Capitol.”

Ambigapathy Ramji, a 23-year-old tourist from Geneva, said he was overwhelmed with shock when he heard of Friday’s shooting and felt compelled to pay tribute to the slain officers by visiting the steps of the Capitol.

“It’s very troubling,” Ramji said. “No one thought something like this could happen.”

Officers to Lie in Capitol As Congress Pays Homage Weston’s Condition Improves; Insanity Defense Expected

Monday, July 27, 1998

The bodies of U.S. Capitol Police officers Jacob J. Chestnut and John M. Gibson will lie tomorrow in the majestic Rotunda of the building where they gave their lives, a farewell usually reserved for the nation’s revered leaders.

The two policemen slain Friday will lie at the Capitol Rotunda throughout the day, an unprecedented honor for the men who died defending tourists and elected representatives. The public will be admitted to pay tribute to the officers from 8 a.m. until 7 p.m., except for a brief period beginning at 3 p.m. when members of the Capitol Police, the officers’ families and Congress will attend a private ceremony. President Clinton and Vice President Gore also plan to attend.

Yesterday, the private and public families shattered by the violence struggled slowly to deal with the aftermath of Friday’s violence. Also yesterday, U.S. Capitol Police Chief Gary L. Abrecht offered his first public comments; authorities continued to search for clues to the suspect’s possible motive; and visitors to the Capitol placed still more flowers on the steps as an expression of their grief.

Meanwhile, Russell Eugene Weston Jr., 41, charged with killing the two officers when he burst into the Capitol on a languid Friday afternoon, was upgraded from critical condition to serious condition by officials at D.C. General Hospital.

Weston, a drifter with unusual suspicions, barged through a metal detector Friday and allegedly executed Chestnut, 58, without warning, and then killed Gibson, 42, in a gunfight.

Law enforcement sources said yesterday that Weston emptied his six-chamber .38-caliber Smith & Wesson pistol; in return, he was wounded in the torso, arms, buttocks and thigh.

Weston is under arrest, held without bond on two federal murder charges, as he lies under heavy guard in the locked ward of the hospital. Charges against him, filed Saturday in D.C. Superior Court, likely will be transferred today to U.S. District Court. The federal court was closed on Saturday, so prosecutors secured an order in D.C. Superior Court to keep Weston in custody.

Law enforcement sources said the prosecution team already is bracing for a possible insanity defense or claim of incompetency, as new details emerged of Weston’s behavioral history, including a 1996 visit by Weston to Central Intelligence Agency headquarters in which he claimed he was a clone and President John F. Kennedy’s son.

Congress is expected to reconvene today with a tribute to the officers. Both houses are to approve the public viewing of the officers’ caskets in the Rotunda, an honor until now afforded only 27 people in the nation’s history. Four were unknown soldiers; all the others were presidents, generals, members of Congress or other dignitaries.

Separate funerals for the men are set for Thursday and Friday, each including a motorcade past the Capitol.

“My thoughts and prayers go out to the families,” said Abrecht, who has met privately with the families. “They were in a great state of grief.”

The police chief said Gibson will be buried on Thursday in Lake Ridge. Chestnut, an Air Force veteran, will be interred the following day at Arlington National Cemetery.

Abrecht said his review of the incident convinced him “our people did exactly what they should have done. They were heroic in every way.” Abrecht, speaking later at a brief news conference outside the Capitol, called his two officers “fallen heroes” and said he could not comprehend how their families were dealing with their deaths with such grace.

Abrecht recounted how, after the shootings, his own teenage daughter “came running up to me and threw her arms around me” in a scene he thought was being repeated in police families all across the nation.

“The past few days have been an extremely trying time for the United States Capitol Police,” Abrecht said. “From the expressions of sympathy which have been pouring in to our department, it is evident that our loss and feelings of sadness are being shared by the United States Congress and the American public.”

In a separate interview, Abrecht recalled that he would often “stop and chat with Chestnut; he was a wonderful, quiet professional police officer. He was steady and unruffleable.” Abrecht said Chestnut had a “friendly but firm manner. He was excellent with the public.”

Jonathan L. Arden, chief medical examiner of the District, said yesterday that autopsies of the two officers Friday night showed that “neither one of them had any significant chance of being able to survive his wounds.”

“Unfortunately, there are some wounds that simply are not survivable,” Arden said. He said Chestnut died of a gunshot wound to the head that penetrated the brain, and Gibson died from a wound to the abdomen with penetration of his aorta.

It is unclear whether Chestnut ever confronted his killer. According to law enforcement sources who have watched a security camera videotape, Chestnut was standing with his back to the metal detector, writing directions for a father and son, when Weston strode through the metal detector and immediately shot Chestnut in the back of the head.

Tourist Angela Dickerson, 24, who was escorting relatives on a Capitol tour Friday, also suffered gunshot wounds during the incident. She was discharged from the hospital Saturday.

A note saying “No Soliciting Please!” was taped to the front door of Dickerson’s family home in Chantilly yesterday. Knocks at the door and calls to the home went unanswered.

Liz Lapham, 44, a neighbor who said she had spoken to Dickerson’s father, said that he told her his daughter was “going to be okay. She’s just really exhausted and resting,” Lapham said. Dickerson, an interior designer, has been married for a year, Lapham said.

“It’s really a tragedy that she was where she was,” Lapham said. “They’re overwhelmed by it.”

Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies continued to study Weston’s life, seeking to understand what may have driven a man considered a harmless nut by neighbors in Illinois and Montana to such bloodshed.

Several hundred law enforcement officers are now working on the case in Illinois, Montana and Washington. Sources said they have executed search warrants at his parents’ home in Valmeyer, Ill., and his shack in Rimini, Mont., an old mining community about 20 miles southwest of the state capital of Helena. They popped open the door to his mountain shack with a crowbar attached to a cable and sent in a remote-control robot to protect themselves from any possible booby traps. None was found.

They also found magazines and a stack of papers with Weston’s diaries and other writings in the red Chevrolet pickup truck the suspect drove from Valmeyer to Washington on Thursday night, the sources said.

A top-ranking law enforcement source said agents searching the home of Weston’s parents in Illinois were looking for writings in a sealed container that might show motive or premeditation.

Weston had come to official notice several times. Citing state laws protecting the confidentiality of medical records, an official at the Montana State Hospital in Warm Springs declined to discuss the specifics of Weston’s treatment at the psychiatric facility during a 53-day stay in late 1996. A court ordered what is known as an involuntary civil commitment for Weston because of repeated threats against Jefferson County law enforcement authorities stemming from a dispute he had with his elderly landlady in 1983.

Weston was discharged from the state hospital on Dec. 2, 1996, and arrangements were made to allow him to prepare his cabin in Rimini for winter and then return to the supervision of his parents in Waterloo, Ill.

In an interview yesterday at their home, Weston’s parents said their son was diagnosed a decade ago as a paranoid schizophrenic.

“I don’t know what you can do about someone like that,” a source at a federal agency said. “If the doctors thought he was okay, how can anyone else predict he’ll go off?”

Law enforcement sources also were studing the details of Weston’s visit on July 29, 1996, to the Langley headquarters of the CIA.

According to a source familiar with a memorandum on the incident, Weston drove up to the main CIA gate off Route 123 and said he had information to report. The source said Weston “rambled on for several hours” to a security officer, explaining that he was the son of Kennedy, that he had been cloned at birth, that Clinton was a clone, that everyone was a clone. He also claimed that Clinton was responsible for the Kennedy assassination because Kennedy had stolen Clinton’s girlfriend, Marilyn Monroe.

“He was clearly delusional, but he didn’t make any threats,” the source said. “If he had, we would have arrested him. But it was just, ‘I’m a clone, Clinton’s a clone, all God’s children are clones.’ He told a bunch of wild stories and drove off into the sunset.”

Weston, who has told his neighbors he believes the government is watching him through satellite dishes, also told the security officer he received “special presidential programming through interactive television and radio.”

Weston ended his visit by informing the officer that he would “report back in 10 or 15 years.” He later sent two letters to the CIA.

The first letter, which was typed, informed the agency that “as timing reverse becomes more aphonic,” he thought he should join the CIA. The second letter, which was handwritten and sent in May, complained that someone had stolen a time device that he had invented. It was signed: “Brigidier General Russell E. Weston.”

Weston’s previous actions could present difficulties for government prosecutors, who have charged him with two counts of murdering federal officers in the performance of their duties, charges that could carry the death penalty.

If Weston’s attorneys question his competency to stand trial, a judge would have to find that he understands the nature of the proceedings and can assist in his own defense before the prosecution could proceed.

If Weston goes to trial, his attorneys might employ an insanity defense — that is, argue that he was not sane at the time of the attack and therefore did not know the wrongfulness of his actions.

“I know that if I were Weston’s lawyer, I’d be thinking about an insanity defense,” one law enforcement official said. “Clearly, it looks like that’s what we’re up against. . . . But there’s a big difference between ‘crazy’ in the vernacular and ‘crazy’ in the legal sense.”

Weston’s past activities and his alleged involvement in the Capitol shootings also have raised anew questions about how federal agencies determine what they consider dangerous behavior, and what they can do about it.

The Secret Service had a routine interview with Weston in the spring of 1996, after learning about comments and letters he had written about Clinton and the federal government. But the agency classified him as a “low-level threat” and did not notify other agencies, although it did keep his name on file. The CIA source said his agency briefed the Secret Service again after Weston’s visit to Langley, but neither agency took any action.

“Obviously, this guy has problems, but lots of people have problems,” one federal law enforcement source said yesterday. “Everyone has a constitutional right to be crazy.”

The CIA official also said his agency’s options were limited in dealing with a delusional but non-threatening individual: “It’s not unusual to have strange people show up at our gate. We treat it seriously, but there’s only so much you can do if laws aren’t broken.”

In their investigation of Friday’s fatal gun battle, authorities have interviewed more than 80 witnesses in Washington, and believe more than 20 of them will be able to help them reconstruct the crime in court, sources said. They said authorities also plan to interview John Broder, a New York Times reporter who said he was approached by a man resembling Weston in Lafayette Square the morning of the shootings. According to the Times, the man pointed at the White House and said: “Millions of people are going to die because of the people you put in that house.”

As authorities concentrated on the official investigation of the shootings, many people seemed drawn to the scene of the crime to leave their own personal tributes.

On the marble Capitol steps, a makeshift shrine of flowers and bouquets grew through the day, even as sightseers returned to wait in line for a tour of the Capitol.

A child-drawn picture with the note “Peace on Earth” addressed a message to the officers: “Thank you for being there and protecting so many.”

Jeanne Gross, 68, came from Germantown with her friend Genevieve Dunbar, 74, to deliver flowers to the Capitol because “it’s sad that they have to give up their lives for someone so demented. They have wives, children, left alone.”

Barbara Rackle, 55, of Gaithersburg, said, “I had to come. This is our heritage,” pointing toward the American flag that whipped, in the stiff breeze, at half-staff above the Capitol. “Our liberty is so costly. Things like this do happen, but I just couldn’t believe it would happen here, in our Capitol.”

Ambigapathy Ramji, a 23-year-old tourist from Geneva, said he was overwhelmed with shock when he heard of Friday’s shooting and felt compelled to pay tribute to the slain officers by visiting the steps of the Capitol.

“It’s very troubling,” Ramji said. “No one thought something like this could happen.”

Staff writers Ceci Connolly, Maria Elena Fernandez, Steven Gray, Nancy Lewis, Bill Miller and Linda Wheeler in Washington, Patricia Davis in Chantilly and Tom Kenworthy in Helena contributed to this report.

Thousands Honor Slain Officers at Capitol

Tuesday, July 28, 1998

Thousands lined the outside of the U.S. Capitol today, waiting to pay tribute to slain U.S. Capitol Police officers Jacob J. Chestnut and John M. Gibson.

By late morning, the crowd to enter the public viewing in the Capitol Rotunda wound down First St. SE to Independence Avenue.

Several hundred remained in line at noon as a hazy sun baked the scene and police temporarily closed the tribute for a viewing by members of Congress. President Clinton, Vice President Gore and others will speak during a 3 p.m. private ceremony and the site should be re-opened to the public from 4 to 7 p.m.

The Capitol parking lot was crowded with mourners, media and tourists, some who were unaware of what they were watching. Some came from their offices. Others interrupted their vacations. But most of those who journeyed to the scene did so to see history and honor heroism.

”There’s just something pulling us,” said Brenda Jones, a Newburg, Charles County, resident who had never before been to the Capitol. ”We just had to go.”

Derek Hamm walked two blocks from his home. He calls the U.S. Capitol Police his neighborhood police.

“It was a little too close to home,” said Hamm, 41, of the Friday afternoon shooting.

He joined the line at 7:45 a.m. when it was more than 200 people deep and reached from the Capitol parking lot to First St., SE. An hour later he climbed the 35 steps to the East entrance, past the growing pile of bouquets and floral arrangements at the foot of the Capitol.

Inside, four officers in full dress uniform stood like statues around the flag-draped coffins. The crowd inched along the outside of the maroon ropes. Many wore solemn stares and clasped their hands. A few carried tissues.

They did not fit into any one category: an elderly woman using a walker; behind her, a couple in jeans with four young children; following them, three professionals in business suits. Many wore stickers of support distributed by the Capitol police and signed a comment book for the slain officers’ families.

One floor below the room buzzed like any summer day, with tourists eyeing exhibits of Capitol history. But there were plenty of signs that this was no typical day.

A black velvet sash draped the doorway of Majority Whip Thomas DeLay (R-Texas) where Gibson was shot. The Document Room entrance, where the shooting began, was closed.

Some staffers walked the halls with blue ribbons pinned to their lapels. Outside the Credit Union office, photos of the slain officers sat on an easel. On the Capitol lawn, bagpipes prepared for the afternoon ceremonies. Police officers gathered from departments in Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut and New Jersey.

The line to enter the building stayed steady most of the morning. The doors were to open at 8 a.m., but were delayed when police found a suspicious package on a motorized cart used by Capitol staff. The package was determined not to be dangerous, but added to the tension.

“This is a difficult day and everyone is on edge,” said U.S. Capitol Police spokesman Dan Nichols.

Bob Mills saw Gibson about once a week last year, when Mills managed DeLay’s re-election campaign. Today, Mills stood in line to see Mills one last time.

Mills remembers talking with the officer last year about the risks of his job. Gibson said he knew he was trained and qualified to handle a challenge like the one that faced him Friday.

”I can certainly say that not only did he meet that challenge, but he far exceeded that,” Mills said, ”by protecting the lives of the people in that office first, and then still having the courage, the bravery and the foresight to stop the attacker.”

Dave Adamson, a special education director from Salt Lake City, Utah, watched the events this morning from the Capitol lawn. His wife and three sons were back at the hotel sleeping before their long trip home today. Adamson didn’t know the officers, has no connection to law enforcement and has never been the victim of a serious crime.

But it was just a week ago, as he and his family arrived in D.C., that he was talking to his three sons about the extraordinary security required to guard the nation’s treasures.

And it was just six days ago that he and his family walked through the same door that suspect Russell Eugene Weston Jr. entered last Friday. Adamson came this morning to witness the tribute, the history. He did not think his sons should see it.

“I brought them to the nation’s capital to see the best of what we have to offer,” he said. “I appreciate the honor of these officers and what they did, but I would not call that [the incident] the best of what we have to offer.”

Funeral Processions Likely to Snarl Traffic

Thursday, July 30, 1998

Today’s funeral procession for slain U.S. Capitol Police Detective John M. Gibson will be at least 12 miles long as it travels a 35-mile route from Prince William County to Arlington National Cemetery, and motorists should expect traffic tie-ups for much of the day, police said.

The cortege will start at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church in Prince William’s Lake Ridge section, after Gibson’s funeral at the church at 10 a.m., then proceed up Shirley Highway to the U.S. Capitol and along the Mall, reaching the cemetery in the early afternoon. Dozens of extra police officers have been called in to deal with expected traffic snarls on adjacent roads.

About 1,000 police cruisers will take part in the procession, and there may be hundreds more cars driven by civilians, said Kim Chinn, a spokeswoman for the Prince William police. Four Metro buses will carry U.S. lawmakers and Capitol Hill police officers and staff members, according to a Metro spokeswoman.

Similar tie-ups will occur tomorrow, when Gibson’s colleague, Officer Jacob J. Chestnut, is buried at Arlington. Chestnut’s funeral procession will leave from Fort Washington, after a 10 a.m. service at Ebenezer AME Church, then move along Allentown Road, Indian Head Highway and Interstate 295 before reaching the District.

Prince George’s County police are asking drivers to stay off Allentown Road this afternoon and evening during a viewing for Chestnut at the church, at 7707 Allentown Rd. in Fort Washington, and again tomorrow morning before and after the funeral.

People “should keep all of this in mind when they make travel plans,” said Virginia State Police spokeswoman Lucy Caldwell. “They should make other arrangements if possible. . . . But due to the solemnity of the occasion, I don’t think people will be complaining, either.”

To help mourners make their way to Seton Church this morning for Gibson’s funeral, police will direct traffic at the Route 123 exits from Interstate 95, starting at 8 a.m., and also will be at every intersection along the five-mile route to the church, Chinn said.

Officials will close Shirley Highway’s 35 miles of car-pool lanes to all traffic at 10 a.m., reserving them for the funeral procession. The lanes are expected to reopen for southbound traffic about 12:30 p.m., as they normally would, officials said.

When the procession reaches the District and moves along Independence Avenue to the Capitol and then along Constitution Avenue to Arlington Memorial Bridge, traffic on cross streets will be blocked along the route, according to U.S. Park Police.

Officials estimated that the church service will end at 11 a.m. and that the burial at Arlington will take place about 12:30 p.m. But they were not sure about those times, and there also was uncertainty about how long the procession will be and its ultimate effect on area traffic.

“The big question mark is how big is the procession going to be. That’s going to drive in large part how many traffic problems there are,” said Steve Kuciemba, who runs the Smart Travel traffic information service for the region. “We’re going to tell people to avoid the area.”

Prince William police base their estimate of a 12-mile-long procession on the funeral three years ago of William H. Christian Jr., an FBI agent slain during a stakeout.

About 2,000 mourners attended his funeral, also at Seton Church, and southbound I-95 was blocked for a half-hour to allow the procession to go the 12 miles to Quantico National Cemetery. According to Chinn, the first car arrived at the cemetery as the last one was leaving the church.

“This funeral could draw three times as many people,” Chinn said. “We’ve had police units from Texas and even from England call to say they are coming. We really don’t know exactly how many people will be here.”

Officials at Arlington Cemetery said they are planning for a procession that is about four miles long. There is no parking lot in the cemetery, and mourners will have to park along the roadways.

“A lot of people will want to pay their respects,” said Dov Schwartz, a spokesman for the Military District of Washington. “Getting close to the grave will be difficult.”

Paying Respects to Slain Police Officers

Thursday, July 30, 1998

The nation’s week-long public mourning over the slayings of two U.S. Capitol Police officers turned to private sorrow yesterday in a quiet church 25 miles south of Washington, as family, friends, colleagues and neighbors of slain Detective John M. Gibson remembered him in silent prayer and hushed words of comfort.

Thirty-one police motorcycles lined the entrance to St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church in the Prince William County community of Lake Ridge as a two-hour afternoon viewing began. Dozens of officers lingered inside the vestibule of the sunlit church, where Gibson’s body, dressed in his dark-blue dress uniform, lay in an open casket beneath a large crucifix, flanked by a two-man police honor guard.

His family, led by his widow, Evelyn, and three teenage children, filled the first six pews on one side of the sanctuary. On the other side, a line of mourners 30 deep at times slowly streamed down the side aisle, people pausing to kneel and say a prayer or lightly touch the dark-wood casket before moving on to say a few words of condolence.

“Thank you, thank you,” Evelyn Gibson said quietly as one mourner after another stooped to take her hand, brush her shoulder or offer an embrace. Kristen Gibson, 17, the couple’s oldest child, stood and hugged several friends and classmates from nearby Woodbridge High School as they came through the receiving line.

The Gibson family arrived at the church about 1 p.m., an hour before the public viewing began. A few minutes later, a second motorcade pulled up to the red-brick building and the widow and children of Officer Jacob J. Chestnut got out. They were met at the church door by the Rev. Daniel Hamilton, pastor of the Lake Ridge parish, and escorted inside, where they spent about 30 minutes with the Gibsons.

The two families met for the first time earlier this week and resolved to help one another get through the shattering ordeal that now connects them, Hamilton said.

Chestnut and Gibson were killed Friday when a gunman burst past a security checkpoint on the Capitol’s first floor and opened fire with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson. In the frenzy that followed, a female bystander and the suspect, Russell Eugene Weston Jr., also were wounded by gunfire.

Gibson, 42, and Chestnut, 58, were both 18-year veterans of the U.S. Capitol Police force, but the two men’s families did not meet until Tuesday’s nationally televised memorial ceremony in the Rotunda of the Capitol that was attended by President Clinton, House Speaker Newt Gingrich and many other dignitaries.

Hamilton described the families’ initial meeting as “a very powerful moment” and said they decided then that they would “go through this together,” each attending the other officer’s wake and funeral as a way to support one another.

“That’s a tremendous statement,” the priest said, “that these two families, united in a grief-stricken moment, are helping one another.”

Chestnut’s viewing will be from 6 to 9 p.m. today at Ebenezer AME Church on Allentown Road in Fort Washington, where his funeral is due to begin at 10 a.m. tomorrow, with burial afterward at Arlington National Cemetery.

Gibson’s funeral will be at 10 this morning at Seton Church, with interment also at Arlington. Prince William County police, advised that law enforcement officers are coming from across the nation to pay tribute to the two slain officers, are bracing for one of the biggest motorcades in recent memory. Gibson’s funeral cortege will travel up Shirley Highway’s car-pool lanes, cross the 14th Street Bridge and then go up Independence Avenue before sweeping past the Capitol and down Constitution Avenue. It then will continue across Memorial Bridge to the cemetery.

Chestnut was an Air Force veteran and automatically entitled to burial at Arlington. Gibson, a native of Waltham, Mass., who did not serve in the military, will be buried in the nation’s most hallowed military cemetery under special permission from Congress. Mourners outside Seton Church yesterday said it was a fitting tribute to a man who gave his life defending others.

“He was really a great street cop. He loved being a policeman . . . and he had the proper instinct to do the right thing,” said Henry Gallagher, of Chantilly, who recently retired after 25 years with the U.S. Capitol Police. Gibson came to his retirement party, Gallagher recalled yesterday, adding, “I’ll miss him a lot.”

Gallagher was accompanied to the church by his son, Drew, 25, who joined the Capitol Police last year and stood tall yesterday in his smartly pressed uniform. “It’s in the blood,” the young man said, describing how he always wanted to follow his father into the fraternity.

Now that he’s there, he said, “it’s very upsetting” to lose a brother officer. “You never think it’s going to be your department, but it’s a fact of life . . . and, unfortunately, it’s part of the job,” he said.

Capitol Police Detective Kim Rendon, who knew both slain officers, said their loss has hit the 1,295-member department very hard, “but having the support of each other and knowing how the whole world feels has helped.”

Hamilton, the priest, said yesterday that the Gibson family is coping “as best as can be expected. When you lose a father and you lose a husband, it’s very difficult.”

Barbara Causseaux, a teacher at Lake Ridge Elementary, where Evelyn Gibson is a school crossing guard, said her heart “just broke” for the couple’s children: Kristen and her two younger brothers, Daniel 14, and Jack, 15.

“We feel like this is part of our family that has a terrible hurt,” Causseaux said, expressing the hope that when the children “do reflect on the last few days, as painful as they are, they will feel such pride . . . that their father gave his life in such an honorable way.”

One of the first to pay her respects yesterday was Andrea Coble, who lives across the street from the church, where she is a parishioner.

Although she did not know the Gibson family, Coble felt moved to dress her own two little girls – Piper, 5, and Misha, 7 – in fancy cotton dresses and big hair bows and lead them by the hand over to the church.

“I wanted to teach my children that law enforcement is something to be honored,” Coble said, “that officers need to be respected. Most of us go to work, sit at a desk, and it’s safe. But for these people, it’s not.”

Nodding toward Piper and Misha, the young mother added: “And I’m letting my girls know that this is someone’s daddy. This is not just someone you saw on TV.”

Two Heroes, Many Tears Escorted by 14-Mile Motorcade, Detective Gibson Is Laid to Rest

Friday, July 31, 1998

On Shirley Highway overpasses, they waved tiny flags as the long funeral cortege passed. On the freeway below, they pulled over and climbed out of their cars, placing their hands over their hearts. On the streets of a grieving capital, small children were hoisted onto their parents’ shoulders to watch this last journey of a hero they never knew.

And on a sultry summer afternoon yesterday, beneath the shade of a red maple tree at Arlington National Cemetery, slain Capitol Police Detective John Michael Gibson was laid to rest.

The 1,000-vehicle motorcade that traveled 35 miles from a Prince William County church to the Mall and then on to Arlington halted lunch-hour routines and, for many, became a somber reminder of American values.

Along the Mall, souvenir and refreshment sales slowed to a trickle, and families picnicking on the grass looked up to catch a glimpse of the hearse carrying the body of Gibson, 42. Office workers, tourists and police officers saluted or placed their hands over their hearts as it passed, some in tears.

The motorcade stretched for more than 14 miles and took about a half-hour to pass by. It began after Gibson’s funeral at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church in Lake Ridge, traveled up Interstates 95 and 395 and went past the U.S. Capitol, where Gibson worked for 18 years and where he was slain last Friday.

Law enforcement officers turned out in droves, from as far away as California and Canada, to lead the tribute to Gibson, whom mourners described as an ordinary man who did an extraordinary thing in sacrificing his life to save others in the shootout.

“You didn’t have to know him personally,” said Sgt. Thomas Maksym of the Nassau County (N.Y.) Police Department, holding a damp handkerchief as he stood at Gibson’s grave site. “You know the risks he faced every day. It could have been you.”

Thousands of onlookers lined the funeral route, waiting in the blistering heat for the cortege to pass. An honor guard of 260 motorcycle officers led the way.

As the procession traveled up Shirley Highway in the center car-pool lanes, vehicles in the north- and southbound lanes pulled to the shoulders, and motorists got out to watch.

About 130 people waited at the Seminary Road overpass in Alexandria, some arriving 90 minutes before the motorcade started to come by at 12:30 p.m.

Christine DeRiso, who once worked for the Montgomery County police, was moved to tears as she watched the long line of police cars and motorcycles. “That’s why they call it a brotherhood,” said DeRiso, 30, of Sterling.

Gibson and another 18-year Capitol Police veteran, Officer Jacob J. Chestnut, 58, were killed when an armed intruder rushed past a security checkpoint in the Capitol. Chestnut was shot without warning near the visitors’ entrance. Gibson, a plainclothes officer assigned to protect House Majority Whip Tom DeLay (R-Tex.), was fatally wounded in an exchange of point-blank gunfire with the assailant. DeLay and others have said that Gibson’s quick actions saved many other people’s lives.

The suspect, Russell Eugene Weston Jr., 41, is in D.C. General Hospital, continuing to recover from his gunshot wounds.

At his funeral Mass, Gibson was remembered as a loving husband and father of three teenage children; a devoted, disciplined law enforcement officer; and a transplanted Bostonian who never lost his accent or his love of baseball’s Red Sox and hockey’s Bruins.

The assembled congregation, which included DeLay and several other lawmakers and Hill aides, quickly filled the 1,500 seats for the 10 a.m. service, spilling over into the nearby parish hall and onto the sidewalks.

When the Capitol Police ceremonial unit arrived, two dozen members quietly exited the bus. While straightening their dress uniforms and buffing their leather straps, the officers kept their hats low over their eyes and shook their heads solemnly. “It’s just too difficult,” one officer muttered as he prepared to get in formation.

Among the last to arrive, walking slowly up the long driveway leading to the red-brick church, were Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) and his wife, Victoria, who held hands as they entered the building. Kennedy said earlier that he empathized with the two officers’ families because “my family, too, has suffered the sudden loss of loved ones, and I know that there is no greater tragedy, no greater sadness for a family.”

Chestnut’s family, who will bury their loved one at Arlington today, also attended Gibson’s services to offer support and comfort to his widow, Lynn, and the couple’s three children. The Gibsons will do the same at Chestnut’s funeral today in Fort Washington.

“John truly loved his work,” Gibson’s longtime friend, Capitol Police Sgt. Jack DeWolfe, said in his eulogy. But his “greatest accomplishment in life was marrying Lynn and having Kristen, Jack and Danny. You were his whole world,” DeWolfe said.

“John, my best friend, I love you. I will miss you,” DeWolfe concluded, his voice starting to crack. “You will be in my heart forever.”

John Arnold, 15, a friend of Jack Gibson’s whose father is also a police officer, said the Capitol shootings were traumatic for officers’ families.

“My best friend just lost his dad, and it could have happened to me,” he said.

Joining the mourners was Holly Balcom-Mensch, who taught both Gibson boys in fourth grade at Lake Ridge Elementary School, where Lynn Gibson is a crossing guard. Balcom-Mensch said she wrote the boys a letter in which she said that their father died a brave man and that his legacy would always be a part of them.

Outside the church, neighbors lined the streets of the quiet suburban neighborhood, awed by the turnout and the emotion evoked by the ceremony. Some offered drinks to police officers and reporters, and one woman sewed a button on an officer’s coat for him.

Shortly after noon, the motorcycles led the cortege away from the church, riding two abreast, their blue and red lights flashing. As the procession turned onto Old Bridge Road, it passed under the extended ladders of two firetrucks, a large U.S. flag suspended between them.

Spectators gathered along the grassy median and shoulders of the road leading to the interstate. They stood in front of shops, gas stations and convenience stores, some with signs, others with more flags, large and small.

In Washington, when the first motorcycles came into view over the 14th street bridge, a hush fell over the crowd, and parents standing two- and three-deep on the sidewalk lifted their children to see the procession.

“As people started watching, there was just a quietness,” said Charles Houston, 51, a truck driver who lives in the District. “When something like this tragedy happens, it awakens something in all of us, and you see a unity among people. This is going to be a part of history, remembered for a long time.”

As the motorcade slowly wound its way around the Mall, onlookers snapped photographs, while others were brought to tears. Bikers, joggers and tourists saluted or held their hands over their hearts as Gibson’s hearse passed them.

Jonathan Stephens, 45, who works for the U.S. Forest Service, said he wanted to show his respect because he once worked as an administrative aide at the Capitol.

“It just gives you the chills to see this,” he said. “The pomp and circumstance of the procession is overwhelming.”

In the crowd of 500 people gathered on the Capitol’s west side was 11-year-old Eugene Herring of Hamilton, N.J.

“This is sad, that a maniac can come to the Capitol and shoot police,” he said, adding that “all these people have come out of respect because those officers did their job as they were supposed to do.”

George Anderson, visiting Washington from his home in Clearwater, Fla., learned that the funeral procession was coming as his family waited in line at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and decided to stay and watch.

“It touched me, the way the whole nation was touched by it,” he said of the shootings in one of the nation’s most treasured buildings. “It’s just [a] horrible waste. One insignificant person made such an impact on so many people today.”

As the hundreds of police motorcycles and cars — first appearing in the summer haze as one giant, unified vehicle — rounded the Lincoln Memorial and started over Memorial Bridge, a red D.C. rescue boat in the Potomac River shot streams of water several hundred feet into the air. A line of officers on horseback met the procession at the cemetery’s front gate.

When a cadre of officers waiting at Gibson’s grave site learned that the motorcade had arrived — more than an hour after it had left the church — they fell silent and snapped to attention. Soon the haunting sounds of police bagpipers from Chicago and New York could be heard across the nation’s most hallowed military cemetery.

Although Gibson was not a military veteran, he was granted special permission to be buried at Arlington. His grave, under a shady red maple tree in Section 28, is in “a peaceful part of the cemetery,” said Arlington historian Tom Sherlock, “off the beaten track.”

As four police helicopters flew past in tribute, several officers in full dress uniforms began succumbing to the heat. Some were led away to air-conditioned buses.

Although not a military funeral, the half-hour service included a 21-gun salute and the sounding of taps. Lynn Gibson, her children seated next to her, was presented with the American flag that had draped their father’s coffin.

At the end of the ceremony, she slowly stood and, leaning forward, placed a long-stemmed red rose on her husband’s casket. Carved into the polished dark wood surface was the name “John Michael Gibson” and the emblem of the police department he so loved.

GIBSON, JOHN MICHAEL, Det., U.S. Capitol Police

Age 42, of Woodbridge, VA on Friday, July 24, 1998 at the Washington Hospital Center. He is survived by his wife, Evelyn (Lyn) Mary Gibson; parents, Charles and Eleanor Gibson; children, Kristen, John Michael (Jack) and Daniel Joseph Gibson. Also survived by one brother, Tech. Sgt. Charles Gibson, U.S.A.F., and his maternal grandmother, Margaret Landis.

The Congressional Tribute honoring Det. John Michael Gibson and Officer J.J. Chestnut will be held at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, Tuesday, July 28, from 8 a.m. until 8 p.m. This will be open to the public with the exception of the hour of 3 to 4 p.m. when the official tribute from Congress will be held.

Visitation will be held at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church in Woodbridge on Wednesday, July 29, from 2 to 4 p.m. and 6 to 8 p.m., where funeral services will be held on Thursday. Father Dan Hamilton will officiate.

If desired, contributions may be made to HEROES INC., 666 11th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20001

Realizing He’s Gone Chestnut’s Family Mourns, Prepares for Service

Friday, July 31, 1998

A week of ceremony, cameras, cards and flowers and sympathetic words from the president of the United States had passed, and the family of U.S. Capitol Police Officer Jacob J. Chestnut was left alone with its grief.

In the hour before hundreds arrived last night to pay respects to the fallen hero, before the widow, Wendy Wenling Chestnut, collected herself to shake every hand, familiar or strange, that reached out to her, the son, daughters, brothers, nieces and grandchildren of J.J. Chestnut wept over the body of a man who set out for work on Capitol Hill a week ago today and never came back.

Alone around the flag-draped open casket, “we finally saw him, and we realized it was true. He was gone,” said Betty Johnson, the officer’s sister-in-law. “The last few days, we didn’t accept it had happened.”

Chestnut, 58, and Detective John M. Gibson, 42, both 18-year veterans of the U.S. Capitol Police force, were killed a week ago when a gunman burst past a security checkpoint into the Capitol and opened fire. A female bystander and the suspected gunman, Russell Eugene Weston Jr., were wounded in the gun battle.

Gibson was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery yesterday after a funeral in Prince William County, his home. The funeral for Chestnut will be at 10 a.m today at Ebenezer AME Church on Allentown Road in Fort Washington. He, too, will be buried at Arlington.

Last night, mourners came to Ebenezer AME Church for a three-hour visitation that drew some of the same people, including fellow officers of the two men, who had spent the day alongside the Gibsons.

Hundreds waited in line to file past the open casket in the church, which Chestnut’s 21-year-old daughter, Karen, attends.

Periodically, an honor guard of three Capitol Police officers marched into the church to leave two and retrieve two officers who stood guard on either side of the baby-blue satin-lined casket.

At one point, about a dozen Capitol Police officers filed solemnly past the rest of the mourners to stand over the casket of their fallen comrade. One officer sobbed as she fell into the arms of Wendy Chestnut, who many times last night was engulfed in the arms of a mourner. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry,” the officer told the widow. “We loved him.”

As an organist played hymns, a line of mourners wound out of the sanctuary to a lobby where, in hushed voices, some talked of a man they never knew and others wept for a friend and fellow police officer.

Margaret Vanzego is a neighbor who remembered Chestnut had walked his children to the bus stop when they were younger. She remembered a husband and wife who used to stroll around the quiet, middle-class neighborhood where they made their home.

“He was a very nice person,” Vanzego said. “He was the type who was always happy. A lot of people are hurting. He was a husband, father and grandfather.”

Inside the church, which can seat 4,000 in the sanctuary and hundreds more in other rooms designed to handle overflow crowds, mourners congregated under a Bible verse that was stenciled high above them: “. . . For mine house shall be called an house of prayer for all people.”

Most who gathered were African American, fellow residents of Prince George’s County, where Chestnut, who was retired from the Air Force, had lived since 1980.

Lyndra Marshall, an administrator at the church, said Wendy Chestnut insisted that the public be able to see her husband and to pay their respects.

“She knew there were going to be a large number of political people, Capitol Police, other police, but she wanted to make sure that the church opened itself to the common people,” Marshall said. “That’s what she wanted, the common people.”

Delores Bennett, a Fort Washington resident, had a beautician whose name was Chestnut. The beautician was a niece of J.J. Chestnut, it turned out, and Bennett said she came last night because “it’s just so awful.”

Michele Washington didn’t know the family, but she works at the Pentagon and sees guards just like Chestnut every day.

“I came to let them know that we care about what they do,” said Washington, a Mitchellville resident.

Chester McKenzie, of Hillcrest, brought his wife. “It was an opportunity to pay my respects to a fallen hero,” he said. “I just think that he should be honored.”

Charlenea Banks, of Mitchellville, said she was sad “for the family and for us, the United States.”

“I think it was something I needed to do because I’m a human being and an American and they were, too,” she said.

Officer Chestnut attended a Baptist church down the road, but his family decided that the much larger Ebenezer church could hold the thousands expected to attend his funeral today.

Marshall said that the church has prepared for 10,000 mourners and that those who cannot be accommodated in the main building will be seated across the street in the old Ebenezer church.

This adopted church family sprang into action two days ago when they were summoned to open “God’s House” to a shocked and somber American people who have grieved for a week over two men who died to protect them, to protect the Capitol, sometimes called the “People’s House.”

Before the 6 p.m. visitation was scheduled to begin, female ushers in white dresses and white gloves stood at the church entrances. A minister rushed into the church office to ask if someone could make sure the flag on the coffin was in the proper place. Parishioners who never knew Chestnut directed traffic and brought in flowers.

Eric Galloway Sr., a member of Ebenezer, prepared plates of fruit and meats for the family to eat. “They needed me, so I came,” he said.

Marian L. Colter, who works with Wendy Chestnut at a computer firm that manages software for St. Elizabeths Hospital in the District, rushed into the church with a tub of turkey salad and a cake that some of her colleagues had made.

She said Wendy Chestnut would survive this most horrible of trials.

“As long as you’ve got God with you, you don’t have to worry about anything,” she said.

Staff writer Nancy Trejos contributed to this report.

Funeral, Procession For Officer Chestnut

The funeral and procession for slain U.S. Capitol Police Officer Jacob J. Chestnut has the potential to disrupt traffic for much of today. All affected roads in Prince George’s County and the District will be closed during the procession, which will begin after the 10 a.m. service. Traffic will be rerouted east of the Capitol and west of Rock Creek Parkway. Police advise commuters and tourists to take Metro.

CHESTNUT, JACOB JOSEPH

On Friday, July 24, 1998. JACOB JOSEPH CHESTNUT was born on April 28, 1940 in Myrtle Beach, SC to the late Rosa Bell and C. Berry Chestnut, Sr. He later moved to Holly Ridge, NC and graduated from Georgetown High School in 1959. He served in the U.S. Air Forcd in 1980 with the rank of Master

Sergeant in the military police field. He earned various high awards, which included the Bronze Star. He also served in the Vietnam War twice. He joined the United States Capitol Police force in January of 1980. He wasalso a very active member in the DAV (Disabled American Veterans), the Tuskegee Airmen Incorporated, a life time member of the VFW (Veterans of Foreign War) and the Air Force Sergeants Association. He

was also a very active citizen with the Tantallon Square Civic Association.

He leaves to fondly remember him, his wife, Wen-Ling and their two children, William Liao and Karen Ling and his granddaughter, JasmineBreana Culpepper, of Fort Washington, MD; son, Joseph Chestnut and grandson, Anton Rashay Spivey of Myrtle Beach, SC; twin daugters Janet and Joyce Allen and granddaughters, Ashtan Ann Netherly and Brandy Dionne Miller, and Janece Jaye Graham and granddaughter, Joyce Jaye Brevard, of Austinther, Herman White and his wife, Margie of Myrtle Beach, SC; brother, Caleb White of Jamaica, NYand youngest brother, Henry White and his wife, Ninette of Youngstown, OH; his half brothers, David Batts, Richard Jones and Daniel Kenan; two half sisters, Marie Dennis and Margaret Lisane; his mother-in-law, Kuei-Chih Chang; his father-in-law, Chien-Chung Liao; his sister-in-law, Wen-Ying Johnson and five brothers-in-law, John W. Johnson, Wen-Kuo Liao, Wu-Kuo Liao, Hsing-Kuo Liao, and Hua-Kuo Liao. Also survived