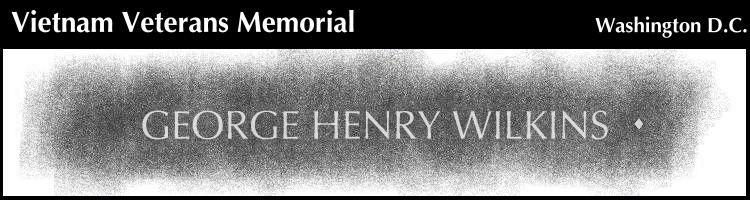

U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander George Henry Wilkins‘ name appeared on a gravestone this past weekend, one more gray granite marker in a city of monuments.

The funeral, held three days before Veterans Day, consisted of full military honors in leafy Arlington National Cemetery.

A Navy band played. A chaplain spoke. Family came, just as families did for the seven other people buried at Arlington that day.

It wasn’t the first time George Wilkins’ family had gathered in his honor. In 1974, though there was no body, the government declared him dead, a belated casualty of the Vietnam War, and the Navy held a memorial service.

Seven years ago, on one of several trips to Vietnam to retrieve bodies of soldiers lost in the war, government officials came back with some remains from the site where Wilkins’ plane had crashed. It would be several more years before scientists, using breakthroughs in the study of DNA, would be able to identify what they had.

But this time, they knew: When they laid Wilkins’ spirit to rest, they laid his body down too.

George Henry Wilkins, born in Angier, North Carolina, and raised in neighboring Johnston County, was career military, as long as his career would last.

After graduating from Benson High School with honors in 1949, he applied for a congressional appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis and was accepted as an alternate in case another candidate did not make the grade. But the other cadet did make it, so Wilkins did the next best thing. He enlisted.

After three years at a Navy base in Virginia, Wilkins was honored with a fleet appointment to the academy. He graduated in 1956 and headed for the Navy flight school at Pensacola, Florida.

“He wanted to be an admiral,” says his brother, Percy Wilkins Jr., a lawyer in Nashville. “And I’m sure he would have been, but things just didn’t work out that way.”

As a young man growing up in a small town, Percy often had been compared to his brother. George Wilkins, two years older, besides being a scholar, was a starter on the school basketball team, a member of nearly every club and owner of what one music teacher called “the best bass voice I’ve ever heard.”

“Pretty big shoes to fill,” Percy, now 63, recalls.

In 1957, George Wilkins married LaVerne Willis. About a year later, they had their first child, George Jr. or “Skip,” as his sister, Cassie, later nicknamed him.

In his early years in the Navy, Wilkins served a number of tours in the Mediterranean. His son remembers traveling overseas with his mother in those days to see him.

During the Vietnam War, the family was living in Lemore, a desert town in Southern California. Wilkins, a jet fighter pilot, served his first tour of duty in Vietnam and came safely home. A few months later he was sent over again.

“That second time, he had a feeling he wouldn’t be coming back,” Skip Wilkins says. “He and my mother talked about it and they both sort of had this feeling.

“Before he left,” he remembers, “we both went and got baptized.”

Confirmation of the fears came in a big, dark car sent by the Pentagon. Skip, 8 at the time, says he and his mother knew the news before the uniformed officers got to the door.

It had happened July 11, 1966, three days before Wilkins’ 35th birthday.

Wilkins, assigned to a destroyer, the USS Constellation, was flying an A4 Skyhawk, a lightweight little craft that was fast and maneuverable, capable of attack and good at providing ground support.

His job that night was to fly over an area about 12 miles outside the city of Vinh on the coast of North Vietnam, in search of truck convoys providing supplies to enemy troops. Using what would now be considered a crude technique, he was to drop flares, which would float to the ground on parachutes, and then make a pass underneath the flares, using their glow as searchlights.

The lower he flew, the better he could see what moved along the roads between the rice paddies, but the more likely he was to get shot.

His wingman, flying alongside in another craft, said he heard Wilkins call, “Flares away!” before a round of anti-aircraft fire hit the A4 and the jet went to the ground.

A daytime search failed to find the wreckage. But the Navy – and Wilkins’ family – were sure he did not survive the crash.

Still, says Percy Wilkins, without a body to bury, “You never completely lose hope.”

Wilkins was officially considered missing in action until 1974, when the government, lacking knowledge to the contrary, declared him dead. In the years that followed, his became one of the “unaccounted for” cases in the Pentagon’s Vietnam War files, those whose fate had never been fully established by the finding of physical remains.

Five years ago, there were still 2,226 of those cases. Each represented a thorn in the side of the U.S. government, which faced claims of everything from ignoring reports of possible live prisoners of war to the prospect of paying outright for information about missing servicemen, something it has said it would never do.

Prodded by the families of servicemen and a number of veterans’ advocacy groups, including one based in North Carolina, U.S. officials established the Defense POW/MIA Office as the lead agency in dealing with unaccounted-for cases.

Theirs is a slow, sad job undertaken in the worst of circumstances. In five years, the agency has spent millions of dollars on searches and excavations, filled a warehouse with items to be studied and used forensic tests on remains as small as a fragment of tooth or a shard of bone to make 130 positive IDs.

Wilkins’ remains were found in 1989. They were brought out of Vietnam with eight others and taken to the lab in Hawaii, where the Defense Department oversees the testing of remains.

DNA from one set of those remains was compared unsuccessfully to that of a blood sample taken from Wilkins’ brother three years ago. Finally, this year, using another set of remains, scientists found the match.

The family got the confirmation July 11, 30 years to the day after George’s plane was shot down.

They didn’t have to talk about it much, family members say; a military burial at Arlington was what Wilkins would have wanted. It is a sprawling place, but elegant and, with its roads named for great generals, fitting for a military man.

As they gathered in Room A of the Administration Building at the cemetery before the Friday afternoon service, Wilkins’ cousins, aunts and uncles, brother and two children had something of a reunion.

They are warm, friendly people with a mix of accents that indicate why some have not seen each other for 20, even 30 years. They live now in Virginia, Tennessee, Florida and Eastern North Carolina, with families of their own.

On cue, they walked into rain to their cars – it was strangely warm and stormy for November – and followed an escort into the fields of headstones. On Patton Drive, they parked, went and stood on a hill under their umbrellas to watch as Wilkins’ casket was taken off the caisson by white-gloved pallbearers and carried to the grave. As many as could then crowded under the

canopy for the brief service.

A lone sailor, standing some distance away, played taps. The band played “America the Beautiful.” And U.S. Navy chaplain Richard Butler, shouting to be heard above the storm, began: “This,” he said, “has been a long time coming.”

News Report: November 12, 1996

Name by name, funeral by funeral, tear by tear, the list grows shorter.

George H. Wilkins of Benson is the latest of North Carolina’s Vietnam casualties to come home. He was buried Friday with practiced pageantry at Arlington National Cemetery.

He joins a dozen or so other Tar Heel MIAs whose names have been solemnly stricken from the sad roll of the missing since the inglorious end of the Vietnam War.

Did Wilkins, a Navy flier, die quickly in honorable combat, only to have his remains recovered and returned to his family this year? Or was he, as so many have feared, one of the unlucky few to remain in the hands of his captors until his lonely death years after the shooting stopped?

Such nightmare scenarios keep many from being able to close the tattered book on Vietnam. Closure, painful but welcome, has come to the Wilkins family. But for as many as 2,000 other American families, the war and the unanswered questions it raised are thorns in their hearts.

Vietnam was different. More than 50,000 men remain unaccounted for from World War II. They, like Wilkins, vanished like shadows, but there was never much realistic hope they had survived. An empty heart back on the home front became their lasting memorial, but their loved ones didn’t stay up at night imagining a fate truly worse than death.

But something happened in the 1960s. A new, loud, questioning generation came of age and went off to fight its own war. And when it was over, the survivors demanded answers.

Where were our missing brothers? Unlike World War II, we could not walk the ground where they fell. We could not comb the records, open the graves, probe the old POW camps and, if necessary, move heaven and earth to find our fallen comrades. All we had to sustain us was the word of an enemy who had, for a decade, held on to French prisoners from earlier battles. Why should we believe them when they said all our men were free?

Indeed, why should we believe when men photographed in prison garb didn’t come home, when hundreds of witnesses came out of enemy lands with terrible tales of work gangs of Westerners, when KGB agents told of Americans being sent to Russia to be debriefed for their technological expertise?

Each month, at high noon on the first Saturday, a handful of veterans and friends with stout hearts and long memories gather at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Capitol Square. They stand solemnly as laminated cards bearing the names of North Carolinians who never came home from Vietnam are passed out.

In voices often choked with emotion, the aging men and women in the ranks, sometimes joined by students, read the names aloud as if saying them to the heavens will keep them, at least in their hearts, alive until next month.

There were more than 60 names on the list a decade ago when the memorials began. Now it is just more than 50.

George Wilkins won’t be on the list next month, and at Christmas, when the candles are lighted around the memorial, there will be one less lonely flame.

Some day, maybe, there won’t be any candles at all. Some day, maybe, there won’t be any names to read.

Some day. Maybe.

Until then, welcome home, George Wilkins, U.S. Navy.

You were never forgotten.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard