From a press report: 6 September 2003

War orphans find each other while searching for their fathers

Courtesy of The Rocky Mountain News

It’s highly unlikely the soldiers knew each other.

Lieutenant George Phillip Gaffney Jr. and Major Earl Robert Kindig shared a legacy of courageous service to their country, which led to the ultimate sacrifice.

Each disappeared on flights over mountainous terrain in New Guinea five weeks apart in 1944, the wreckage undiscovered for 54 years.

Finally, there’s another piece to their legacy: love.

Their only children, who met while searching for their fathers’ remains, were married in June and live in Lakewood, Colorado.

Patricia Gaffney wasn’t born when her father perished. Michael Kindig was 3. Both their mothers remarried and they were integrated into new families, but grew up with a sense of loss and longing.

“My mother did speak of my father with love and respect. I did know his family and had some pictures of him. I also had a sense of being different and isolated,” Patricia said.

“We never really knew. That leads the mind to imagine and give some possibility that they survived. I grew up thinking perhaps he was living with the native people, that he had amnesia and he was looking for me.”

Kindig was adopted by his mother’s new husband, an Army doctor.

“My father became a mythic figure with no dimensions. Not until my 21st birthday when I inherited a trunk with his dress saber, letters and journals did I get a sense of the awful loss of what I’d been deprived of,” he said. “That fueled my search.”

The War Orphans Education Act paid for their college education. Michael settled in Colorado, where, known by his adoptive name of Michael Osborn, he became editor of the Colorado Labor Advocate and an actor. Patricia lived in New Haven, Conn., and built a career in arts and education.

Ten years ago, Patricia was watching ABC’s Good Morning America and saw an interview with Janice Olsen, a shopping mall manager from California who tracked down World War II plane crashes in New Guinea in her spare time.

“I contacted her through ABC and we became fast friends,” Patricia said. “She helped me go through the documents I had and the value of them. Eighteen months later I went to New Guinea and went to the places my father had been. It was a very emotional and liberating experience.”

Eventually, Patricia met Alfred Hagen, a Philadelphia businessman who had been to New Guinea seeking the wreckage of his great-uncle’s plane. In the fall of 1997, Hagen went back to New Guinea, stopped at a village in the Finesterres Mountains and asked the locals if they knew of any wrecks. They directed him to two sites, one of which was a plane that matched the one Patricia’s father had piloted.

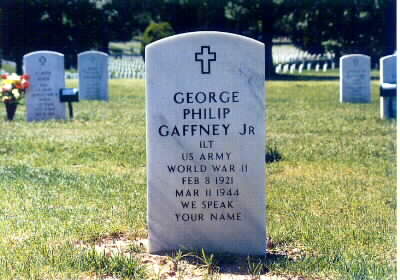

A team from the Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii (CILHI) identified the plane and found remains that led to confirmation through dental records she had obtained that they belonged to her father. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in 1999.

“My mother is still living and she said this had given her a sense of peace she hadn’t known in 55 years,” she said.

Patricia and Michael had each discovered the American WWII Orphans Network (AWON), a support, service and resource organization for World War II orphans. Patricia, who has since become AWON’s president, announced on the group’s Web site that she had found her father’s remains. Michael saw the posting, noticed it was the same area where his father vanished, and contacted her.

Going over notes from Hagen’s earlier trip, Patricia noticed a footnote that said he’d found a plane that matched the type Michael’s father had been in.

In March 2000, a CILHI team discovered remains including bones and a Zippo lighter. However, they couldn’t distinguish the remains of Michael’s father and the plane’s pilot, and his best hope seemed to be a joint internment.

“They needed mitochondrial DNA from my mother, sister or aunt. I wasn’t eligible and was losing hope but they tracked down my 92-year-old great-aunt and got a stone lock match. In October 2001, my father was laid to rest in Arlington, about a block away from George P. Gaffney Jr.,” he said.

Michael’s wife, Denver journalist Sherry Keene-Osborn, died in February 2000.

“A year or so after that, our relationship began to shift a little bit,” said Patricia, who had been divorced for more than 20 years.

They met for the first time in October 2002, at AWON’s national convention in Branson, Missouri. Both were smitten.

When Michael returned to Denver, he went straight to the Shane Co. and bought an engagement ring. Over the Thanksgiving weekend he proposed and they commenced a cross-country relationship.

“I can negotiate DIA blindfolded,” Michael joked. They were married June 28, which he recently verified “was the date Fred Hagen came upon my father’s wreck site.”

Part of their honeymoon was a stop at Arlington to pay respects to their fathers.

“We have come to the conclusion that there’s something mysterious about this, that may be the only word that describes it; that we’ve been essentially looking for each other going back to the days of World War II,” Michael said.

“We tend to credit our fathers, whose nicknames were Bub and Duke. Neither of us is particularly spiritual but this is an area we step aside from and shake our heads.”

From a contemporary press report: 10 June 1999

Patricia Gaffney-Ansel grew up with no memory of her father, with nothing more than a battered leather suitcase that sat in her attic, bearing faded newspaper clippings and letters of a life that ended three months before she was born.

The suitcase “had a presence,” she said. “It was always there.”

In March 1944, at the height of World War II, 23-year-old Second Lieutenant George Gaffney’s P-47 Thunderbolt had disappeared in a rugged mountain range in New Guinea after a bombing raid on a Japanese base. A search by his squadron turned up nothing.

“There was always this knowledge that there would never be an answer,” Gaffney-Ansel said. “I would never know him. There was no way of learning what happened.”

But yesterday, Gaffney-Ansel capped an extraordinary six-year quest by escorting her father’s horse-drawn remains as he was buried with honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

The journey to fill the void in her life took her to the very mountains and jungles where her father disappeared, and along the way, many picked up her cause. There were pilots and other World War II orphans who helped with her search; villagers in remote parts of New Guinea who knew of aircraft wrecks deep in the mountains; a Philadelphia businessman who, searching for his great-uncle’s plane, found Gaffney’s last year; and Army investigators who trekked to the site, recovered the remains and positively identified them as Gaffney’s.

As four Air Force A-10 Thunderbolts soared over Arlington in a missing-man formation to salute her father, Patricia Gaffney-Ansel looked at the sky and smiled.

George Gaffney had barely begun his life with Ruth Christensen when he went off to war. Gaffney, born and raised in Madison, Wisconsin, had met the beauty school student at a high school dance. He had already enlisted in the Army Air Corps when he proposed, and they were married in August 23, just after he finished pilot training.

“He had an Irish wit about him,” said his widow, who remarried and now goes by Ruth Kalupy. “He loved to read, and he loved to dance.”

They spent a few hectic months together before Gaffney had to leave his pregnant wife to join the 5th Air Force in the Pacific. He arrived in Port Moresby, New Guinea, on Christmas Eve 1943. The island had been the scene of some of the deadliest fighting of the war.

Gaffney joined the 41st Fighter Squadron in February 1944 at a base at Gusap. The squadron was engaged in furious bombing and strafing runs over wide areas of northeast New Guinea. Gaffney was flying the P-47, a single-seat fighter bomber that pilots loved.

From Gusap, Gaffney wrote regular letters home describing the war and asking for news of the home front. He could not contain his excitement about the baby on the way.

On March 10, he wrote his last letter home. He described the lovely, soft sound made by the breeze blowing through the tall kunai grass surrounding the airfield. “Did not fly today,” he added. “Due tomorrow, however.”

The next morning, Gaffney joined the squadron’s attack on a Japanese base, skirmishing with enemy fighters. Gaffney became separated from the squadron and landed for refueling at a small Allied field.

Gaffney “appeared rather nervous,” officers there reported. The pilot reported having shot down a Japanese plane and said his aircraft may have been hit. An inspection found no damage, and Gaffney took off for Gusap. It was only 20 minutes away, but his flight took him over the Finesterre Mountains, a formidable, jungle-covered range rising above 12,000 feet and often shrouded with clouds that made flying treacherous.

He never made it. The squadron searched for three days but found no sign of him. Squadron mates wrote kind letters to Gaffney’s family, expressing hope that because his plane went down in friendly territory, he might soon show up.

Back in Wisconsin, the telegram reporting that Gaffney was missing was met with disbelief, particularly with a baby due. “Dear God, please bring our Georgie back, don’t let this child grow up not knowing her father,” one of Gaffney’s aunts wrote nearly every day in her diary for almost five years after her nephew disappeared.

But that is how Patricia Gaffney grew up.

She married at 19, raised two children, went to college on the GI bill and got divorced. She worked as a teacher and a curriculum developer for the public schools in New Haven, Connecticut.

Going through her father’s suitcase one day in 1986, she found herself growing unexpectedly upset. “I was angry that I was never going to have my father,” she said.

Everything changed in September 1993, when Gaffney-Ansel heard a researcher on a television program describe how World War II crash sites were still being discovered in Papua New Guinea, as the country has been known since it gained independence in 1975.

“It was a life-changing moment, and I knew it,” Gaffney-Ansel said. “My heart was pounding so hard. This is a crack in the door, and I have to reach into it.”

She immediately contacted the researcher, Janice Olson, who put her in touch with people and groups, such as the American WWII Orphans Network, that could help her. She obtained war records from the military. Her mother put her in touch with men who had served in his squadron. Sheattended their reunions and listened to their tales.

In May 1995, she jumped at the chance to join Olson on an expedition to Papua New Guinea. Once there, pilot Richard Leahy flew her to Gusap, the now-abandoned airfield where her father had been based.

Gaffney-Ansel brought along a metal box, containing letters she, her children and her mother had written to George Gaffney, along with other personal treasures. Walking out into the kunai grass her father had described hearing a half-century earlier, she buried the box.

“I stood listening for that sound,” she said.

Leahy flew her on her father’s route over the Finesterre.

“I felt like I was meeting the enemy — the mountains that took my father,” she said.

Gaffney-Ansel realized more than ever how unlikely it was that she would ever find her father. “I suddenly became aware for the first time how it is that a man just goes missing,” she said.

Her quest came to the attention of Fred Hagen, a Philadelphia businessman who was conducting a search in Papua New Guinea for the wreck of the plane flown by his great-uncle. During a visit in November 1997, Hagen and Leahy found the wreck of a B-25 bomber and the remains of nine men. Villagers told them of another wreck a four-day walk away in the mountains.

Hagen returned with a team the next June and, traveling by helicopter, found a crash site at 8,000 feet, in a beautiful jungle draped with huge ferns and orchids. The plane was shattered and the wreckage covered with mud, but Hagen could tell by the propeller that it was a P-47. Lying amid the wreckage were a pocket watch, a .45-caliber handgun and human remains.

The Army sent a team of investigators who confirmed that the plane was Gaffney’s by the serial numbers on the machine guns.

Gaffney-Ansel had something the Army could use to check the identity of the human remains: her father’s dental records, which had been kept in the old suitcase. In January, the Army confirmed that the remains were Gaffney’s.

“When I got the news,” Gaffney-Ansel said, “I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry, so I actually did a little of both.”

Gaffney-Ansel flew last week to Hawaii to escort her father’s remains home to Wisconsin, where a funeral Mass was held in Madison on Saturday.

“I feel victorious, really,” said Gaffney-Ansel. “I feel I’ve been able to bring my father out of the past and into the present. I’ve been able to develop a daughter’s love for her father.”

After the ceremony at Arlington, she stood with her mother, aunt and two children in front of her father’s casket. Clutching to her heart the folded flag that had draped his remains, she kissed her hand and placed it on the casket.

“It was hard to leave him,” she said afterward. “It’s bittersweet, really. My time with him was very short.”

Gaffney, George Philip Jr, Born 8 February 1921, Died 11 March 1944, US Army, Second Lieutenant.

Section 66 Grave 5619, buried 9 June 1999.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard