By Stefan Cornibert

The Connection Newspapers

October 1, 2004

First in an occasional series on Arlington’s history.

To many black families in Arlington, Freedman’s Village is a legend, a story handed down by great-grandparents of a place that no longer exists. Yet it was in Freedman’s Village — a camp of former slaves established by the government during the Civil War era — that much of Arlington’s modern black community began. As urban development changes neighborhoods like Nauck and Halls Hills, neighborhoods with predominately black populations, historians and preservationists are now looking closer at Freedman’s Village as a lost chapter of the African American community’s history.

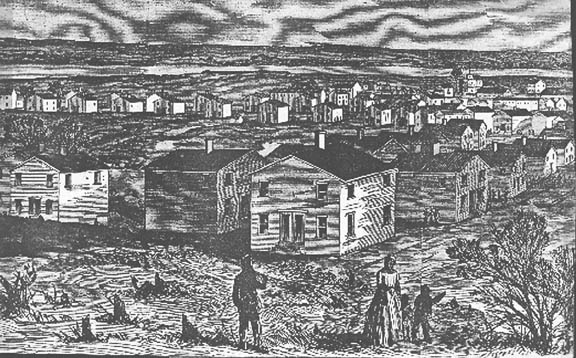

Freedman’s Village was established by the federal government in 1863 on the grounds of the Custis and Lee estates, what is today Arlington National Cemetery, the Pentagon and the Navy Annex building. The village was a collection of 50 one-and-a-half story houses. Each house was divided in half to accommodate two families. The freed men and women — often referred to as contrabands by the government — had all traveled north from parts of Virginia, the Carolinas and other regions of the south in the hopes of finding work and opportunity. Under the direction of the government and the American Missionary Association, the Freedman’s Village was intended to house these refugees, train them in skilled labor and to educate freed children. The camp’s grounds included an industrial school, several schools for children, a hospital, a home for the aged and churches. But Michael Leventhal, Arlington County’s historic preservation coordinator, said Freedman’s Village’s creation had less to do with helping blacks integrate into free society and more to do with segregation.

“Although slavery was abolished, the North was not really interested in having blacks coming into northern cities,” Leventhal said. “It isn’t as if the country had made the full leap to integration.”

The able-bodied residents of Freedman’s Village had to work, often put to difficult labor on construction projects and farming. They were paid $10 each week but half of their salary was turned over to the camp’s authorities to pay for overhead costs. According to the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy, although the village operated several farms, their produce was sold by the government to consumers in Washington D.C. As a report from the New England Society of Friends, a Quaker group, noted in 1864, residents of the village lived “entirely under military discipline”, discipline doled out by soldiers from Fort Myer, and were “obliged to live solely on military rations”. The report describes many in the village wandering nearby roads to beg for food. After a brief period of employment in the village, residents had to leave in order to seek jobs elsewhere and make room for new arrivals.

“We found that they were glad to leave,” the report said.

The village had only one source of water, a well. It was also constructed on what was then a swamp, which caused several outbreaks of smallpox. Yet despite hardships, the village was always seeing new residents and refugees.

Genealogically, many families in Arlington can trace their roots back to residents of Freedman’s Village. Names common in modern Arlington, are found on the village’s registry, names like Gray, Tippet, Parke, Pollard and Syphax.

Craig Syphax, researcher and coordinator for the soon-to-come Arlington Black Heritage Museum, said the legacy of Freedman’s Village endures as a part of the local black community’s social consciousness.

“It’s something that’s has guided the black community, something it has followed by trying to be a self-sufficient community,” he said. “It was a place where freed slaves has a chance to create their own community.”

SYPHAX’S ANCESTOR, William Syphax, a former slave on the Custis estate, left Freedman’s Village and was later elected to the Alexandria County Board. He only served for six months before winning a seat as a delegate in the Virginia General Assembly. In 1870, Syphax petitioned Congress to obtain a 17-acre plot of land near the village.

“We have a claim on this estate,” he wrote.

Other notable residents of the village include Jesse Pollard, the first black judge in Arlington’s history. Sojourner Truth, who worked to smuggle slaves out of the south on the Underground Railroad, also lived in the village for one year in 1864, serving as a teacher and helping to find jobs for villagers. According to Talmadge Williams, president of Arlington’s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), many laborers in Freedman’s Village worked on the construction of the capitol building. In 1866, the Army recruited the 107th regiment of U.S. Color Troops from the village. No one has ever undertaken an organized excavation of the Freedman’s Village site but Williams said that when construction crews were laying a foundation for the nearby Sheraton Hotel, part of the village cemetery was uncovered.

The residents of Freedman’s Village often found themselves at odds with the society outside its limits. As Washington D.C. expanded, land speculators pressured the government to close the camp. Tensions heightened after the superintendent of Arlington Cemetery, J.A. Commerford, accused village residents in 1887 of cutting down trees on cemetery property. Leventhal said the large in-flux of blacks in the area was also a problem for some racially charged whites.

“As the black population became more and more prominent, the camp started getting overcrowded,” he said. “Many spilled out into other parts of Arlington.”

Freedman’s village was closed down in 1900. At its height, it housed more than 1,100 residents yet it was only constructed to contain about 600. One unnamed reporter from the New York Herald noted days before it was shut down that the closing was mostly due to encroaching development, local plans for the expansion of Mount Vernon Avenue and the coming bridge over the Potomac.

“There is also a political element to the case,” the reporter added. “The votes cast by the colored citizens on the Arlington reservation have several times controlled elections in the county.”

After Freedman’s Village was shut down, local farmers, many of them black, others sympathetic to the plight of the freed slaves, offered land to village residents. These plots became neighborhoods like Halls Hills and Nauck.

As Arlington’s black community plans the creation of a museum devoted to its history, Leventhal said the importance of Freedman’s Village cannot be underestimated.

“The truth always falls between the cracks,” he said. “While things are changing in Arlington in terms of development, we’re starting to lose some of the history and the people that made Arlington what it is. It’s important that these folktales and myths become reality.”

An exhibit on Freedman’s Village, including a scale model, is on display at Arlington House, the former estate of Robert E. Lee in Arlington Cemetery. The Black Heritage Museum’s web site, www.arlingtonblackheritage.org, is also expected to carry an exhibit on Freedman’s Village in the coming months.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard