Francis Lupo

- Private, U.S. Army

- 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division

- Entered the Service from: Ohio

- Died: July 21, 1918

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

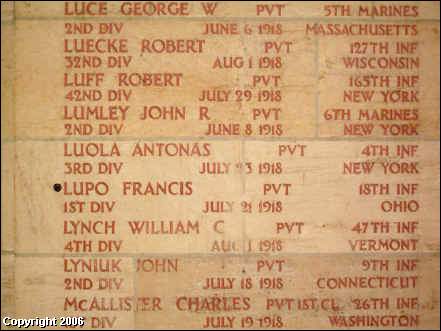

- Tablets of the Missing at Aisne-Marne American Cemetery

Belleau, France

NEWS RELEASES from the United States Department of Defense

No. 942-06 IMMEDIATE RELEASE

September 22, 2006

Public/Industry(703) 428-0711

First Identification of U.S. Soldier Missing in Action from World War I

The Department of Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) announced today that the remains of a U.S. serviceman, missing in action from World War I, have been identified and returned to his family for burial with full military honors.

This is the first time the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) has identified a soldier unaccounted for from World War I.

He is Army Private Francis Lupo of Cincinnati, Ohio. He will be buried on Tuesday, September 26, 2006, at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C.

Representatives from the Army met with Lupo’s next-of-kin to explain the recovery and identification process and to coordinate interment with military honors on behalf of the Secretary of the Army.

In 1918, Lupo participated in the combined French-American attack on the Germans near Soissons, France, in what came to be known as the Second Battle of the Marne.Despite heavy Allied losses, this battle has been regarded as a turning point in the war, halting and reversing the final German advances toward Paris.

Lupo, a member of Company E, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, was killed in action during the battle, but his remains were never recovered.

In 2003, while conducting a survey in preparation for a construction project, a French archaeological team discovered human remains and other items a short distance from Soissons.Among the items recovered were a military boot fragment and a wallet bearing Lupo’s name.The items were given by the French to U.S. officials for analysis.

Among other forensic identification tools and circumstantial evidence, scientists from JPAC and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory also used mitochondrial DNA in the identification of Lupo’s remains.

For additional information on the Defense Department’s mission to account for missing Americans, visit the DPMO Web site.

Pentagon identifies WWI remains

22 September 2006

For the first time, a Pentagon group charged with finding and identifying U.S. war dead from foreign battlefields has identified the remains of a soldier killed in World War I, officials said Friday.

Army Private Francis Lupo, of Cincinnati, Ohio, was killed on July 21, 1918, during an attack on German forces near Soissons, France. His remains were discovered by a French archaeologist in 2003 and identified by scientists from the Pentagon’s Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory.

Lupo is to be buried on Tuesday at Arlington National Cemetery.

He was 23 years old when he was killed.

Larry Greer, a Pentagon spokesman on POW-MIA issues, said it was the first time the remains of a World War I service member have been recovered and identified since the Pentagon established an office in the 1960s with the specific mission of identifying war dead from abroad. He said available government records do not indicate when or whether World War I remains had been recovered and identified prior to the 1960s.

The Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command has recovered and identified hundreds of U.S. war dead from other conflicts, including World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and Cold War-era aircraft shootdowns.

Lupo was a member of Company E, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division when his unit fought as part of a combined French-American attack on German forces near Soissons in what came to be known as the Second Battle of the Marne. Some have called that battle a turning point in the war, halting German advances toward Paris.

Of the 1st Infantry Division’s 12,228 infantry officers and enlisted soldiers who fought in the Second Battle of the Marne, all but 3,923 were killed, wounded, taken prisoner or listed as missing, according to a Pentagon historical report. Lupo was reported missing-in-action, and no witness report or statement concerning the circumstances of his loss appears in the available records, the Pentagon report said.

Lupo’s name was memorialized on the list of missing soldiers inscribed on the walls of the memorial chapel at the Aisne-Marne American Military Cemetery near the village of Belleau, not far from where he was killed.

A total of 116,516 U.S. service members died in World War I, of which 53,402 are recorded as battle deaths, according to the Pentagon. The United States entered the war in April 1917 and it ended in November 1918.

Greer said Lupo’s remains were one of two sets recovered at the same time at the same site. The other set of remains is believed to also be an American soldier but scientists have not yet positively identified them, Greer said.

Eighty-eight years after he fell in battle near the Marne River east of Paris, the remains of U.S. Army Pvt. Francis Lupo of Cincinnati have been recovered and identified by the Pentagon.

On Tuesday, Lupo’s niece and next of kin, Rachel Kleisinger of Florence, will be at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington for his burial.

Lupo had been missing in action since July 21, 1918, after an attack on German forces near Soissons, France.

His skeletal remains, plus fragments of a military boot and a wallet bearing his name were discovered at the site of a conservation project near Ploisy by a French archaeologist in July 2003.

The remains were identified by scientists from the Pentagon’s Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory.

Lupo is the first World War I casualty to be recovered and identified by the special command.

Kleisinger wasn’t born when Lupo was killed, but vividly remembers a portrait of him in his Army uniform in her grandparents’ home.

“It was quite a striking picture – a very handsome boy,” Kleisinger said.

“The look on his face showed a lot of pride to be in that uniform.”

She said the family didn’t talk about him much out of respect for her grandmother, Anna Lupo, who was Francis’ mother.

“For a long time she always thought he’d come home,” said Kleisinger. “I think deep down she knew that he wouldn’t, but she wouldn’t acknowledge it.”

Lupo was 23 when he was killed in some of the fiercest, most gruesome fighting of the war. He was a member of Company E, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division when his unit fought as part of a combined French-American attack on German forces near Soissons in what came to be known as the Second Battle of the Marne. Some have called that battle a turning point, halting German advances toward Paris.

Army historical records say Lupo’s group was advancing toward Chaudun, about 1.5 miles southeast of Ploisy, as the 1st Infantry’s four-day attack began.

Larry Greer, a Pentagon spokesman on POW-MIA issues, said this is the first time the remains of a World War I service member have been recovered and identified since the Pentagon established an office in the 1960s with the specific mission of identifying war dead from abroad.

Kleisinger said the Army contacted her last winter by phone and told her the remains had been found – but she wasn’t buying it.

“I thought, ‘This isn’t right,’ ” Kleisinger said. “This man’s been dead almost a hundred years and now they say they found him? I didn’t believe him.” After several more phone calls, a letter and personal visit from Army representatives in March, Kleisinger realized this was real.

The Army is paying for a visitation Monday and the funeral Tuesday. They’re also paying for Kleisinger and three of her family members – daughter Rose and son-in-law Bob Nicely, and their son Brian, all of Edgewood – to make the trip.

Kleisinger said the Army is handling the service, but she did make one request, which she said the Army has agreed upon: that a Catholic priest be at the funeral.

“Francis was a good Catholic boy, his mother was a good Catholic lady, and if she were alive she’d say, ‘You better believe there’s going to be a Catholic priest there,’ ” Kleisinger said.

Kleisinger has been given the piece of Lupo’s boot and wallet, along with a prayer card he had with a picture of St. Therese. “I’m going to put them in a safe place,” she said. “I have grandchildren this will be of interest to.”

She said the whole experience has made her proud of her uncle.

“This is a very proud thing,” Kleisinger said. “It’s a great honor and he deserves to be honored. I just regret that I didn’t know him.”

A piece of a size 5½ military boot found at a construction site in France helped Pentagon scientists identify the remains of a missing Cincinnati soldier killed during World War I.

Army Pvt. Francis Lupo’s remains will be buried with full military honors Tuesday in Arlington National Cemetery outside of Washington, nearly nine decades after he was killed during an attack on German forces near Soissons, France.

A French archaeological team discovered Lupo’s remains in 2003 while doing a survey in preparation for a construction project not far from Soissons.

The recovered items included bone fragments, dental remains, a wallet with Lupo’s name engraved in gold and a piece of a military boot that appeared to be a size 5 or 5½ .

By digging through Lupo’s personnel file, Army scientists discovered that the young soldier stood just 5 feet tall, weighed 120 pounds and wore a size 5½ boot.

“The 5-foot-high was apparently the shortest recorded stature of any soldier in World War I,” said Larry Greer, a Pentagon spokesman who works on POW-MIA issues. “That helped in the ID process. The bones, the skeletal remains that they had, indicated that this was a very, very, very short person.”

The discovery marks the first time that a Pentagon group charged with finding dead service members has identified the remains of a soldier killed during World War I, Greer said.

The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command was founded in the 1960s to find and identify soldiers missing on foreign soil. Greer said there are no government records indicating that World War I remains had been recovered and identified prior to the 1960s.

Very little is known about Lupo, except that he was born in Cincinnati on Feb. 24, 1895, and at one time was employed as a supply man by the Cincinnati Times-Star newspaper. He was 23 when he was killed.

Lupo never married and had no children.

His closest living relative is a niece, Rachel Kleisinger of Florence. Kleisinger said Lupo had eight siblings, all now deceased, and that the family lived in a house on Ninth Street in downtown Cincinnati.

Kleisinger, 73, wasn’t born when her uncle died. But she said her grandmother talked about him from time to time.

“She was always sad when his name would come up,” Kleisinger said. “She really had a hard time getting over it. She just couldn’t image that he was gone.”

Lupo was a member of the Army’s Company E, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division.

He was killed on July 21, 1918, during what came to be known as the Second Battle of the Marne. Despite heavy Allied losses, the battle is regarded as a turning point in the war, halting and reversing the final German advances toward Paris.

Of the 1st Infantry Division’s 12,228 infantry officers and enlisted soldiers who fought in the Second Battle of the Marne, all but 3,923 were killed, wounded, taken prisoner or listed as missing, according to a Pentagon historical report.

Lupo was reported missing-in-action, and no witness report or statement concerning the circumstances of his loss appears in the available records, the Pentagon report said.

Lupo was listed on a monument outside of Soissons containing the names of all American servicemen who fought in the region during World War I but never returned from battle.

After his death, the Army took his mother to France, Kleisinger said.

“All of these years, I thought she went there and saw a grave where he was buried,” she said. “But it wasn’t. It was just a name on a wall.”

The French archaeologists discovered Lupo’s remains and those of another soldier at the same burial site in 2003. Military scientists used DNA to separate the two sets of remains and help identify Lupo. The other soldier has not yet been positively identified, Greer said.

The discovery of Lupo’s remains was featured in a British Broadcasting Corp. documentary earlier this year.

A genealogist traced Lupo’s family tree to Kleisinger, who will attend Tuesday’s services at Arlington National Cemetery with her daughter, Rose Nicely of Edgewood.

“I’m sorry that I never got to know him,” Kleisinger said.

26 September 2006:

The only testament to Francis Lupo’s death in a World War I battle has long been his name, etched on a French chapel wall with those of hundreds of other missing soldiers.

On Tuesday, 88 years after he was killed, the recently discovered remains of the U.S. Army private were buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

And by year’s end, his name will be carved anew, this time on a white headstone like those marking the graves of his fellow soldiers.

Lupo is the first World War I soldier whose remains – a few fragments of bone and teeth – were recovered and identified by the Pentagon’s office for POW-MIA affairs, Pentagon spokesman Larry Greer said.

About 50 people, including two representatives of the French military, attended Tuesday’s ceremony. Lupo’s niece, 73-year-old Rachel Kleisinger of Florence, Kentucky, sat in a wheelchair as a traditional gun salute – seven rifles firing three rounds – sounded and an Army bugler played taps.

Then Kleisinger – who was born after Lupo’s death but knew his mother – accepted the burial flag from a U.S. soldier.

The military added an Army dress uniform and Lupo’s medals: A Purple Heart and the World War I Victory Medal. The victory medal had clasps for the battles he fought in – Mont Didier-Noyon, Champagne-Marne, Aisne-Marne – before he died during an attack on German forces near Soissons, France, on July 21, 1918.

Lupo, from Cincinnati, was 23 when he was killed. A French archaeologist discovered his remains in 2003 while working on a conservation project.

It took the Army more than five months to find Kleisinger, Lupo’s next of kin, and another six months to make funeral arrangements, Greer said.

Study of Lupo’s remains, found with a fragment of a combat boot and a wallet embossed with his name, showed he stood about five feet tall. That is “very, very small for a soldier headed for combat,” Greer said.

The fighting Lupo saw was some of the fiercest and most gruesome of the war. An anonymous extract from the diary of an officer in Lupo’s unit, later reprinted in an Army history of the war, described the artillery and aerial attacks in stark terms: “Oh, how maddening are these horrible bloody sights! Can it be possible to reap such wholesale destruction and butchery in these few hours of conflict?”

Lupo was a member of Company E, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. His unit fought as part of a joint French-American attack on German forces near Soissons, in what became known as the Second Battle of the Marne. Army records say Lupo’s brigade was advancing toward Chaudun, about 1.5 miles southeast of Ploisy, as the 1st Infantry’s four-day attack began.

Of the 1st Infantry Division’s 12,228 infantry officers and enlisted soldiers who fought in the Second Battle of the Marne, all but 3,923 were killed, wounded, taken prisoner or listed as missing, according to the Pentagon. Lupo was reported missing in action; available military records give no other details.

Lupo’s name was memorialized on the list of missing soldiers inscribed on the walls of the memorial chapel at the Aisne-Marne American Military Cemetery near the village of Belleau, not far from where he was killed.

A total of 116,516 U.S. service members died in World War I; 53,402 are recorded as battle deaths, according to the Pentagon. The United States entered the war in April 1917; it ended in November 1918.

26 September 2006:

A Cincinnati man long listed as missing in action in World War I has finally returned home.

Private Francis Lupo, of Cincinnati, Ohio, was killed on July 21, 1918, during an attack on German forces near Soissons, France.

His remains were discovered by a French archaeologist in 2003 and identified by scientists from the Pentagon’s Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory.

He was 23 years old when he was killed.

Tuesday, Lupo was interred at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. An Army honor guard carried him to his final resting place, while French military officers greeted family members as they sat at graveside.

Larry Greer, a Pentagon spokesman on POW-MIA issues, said it was the first time the remains of a World War I service member have been recovered and identified since the Pentagon established an office in the 1960s with the specific mission of identifying war dead from abroad.

He said available government records do not indicate when or whether World War I remains had been recovered and identified prior to the 1960s.

Lupo was a member of Company E, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division when his unit fought as part of a combined French-American attack on German forces near Soissons in what came to be known as the Second Battle of the Marne.

Some have called that battle a turning point in the war, halting German advances toward Paris.

Of the 1st Infantry Division’s 12,228 infantry officers and enlisted soldiers who fought in the Second Battle of the Marne, all but 3,923 were killed, wounded, taken prisoner or listed as missing, according to a Pentagon historical report.

Lupo was reported missing-in-action, and no witness report or statement concerning the circumstances of his loss appears in the available records, the Pentagon report said.

Lupo’s name was memorialized on the list of missing soldiers inscribed on the walls of the memorial chapel at the Aisne-Marne American Military Cemetery near the village of Belleau, not far from where he was killed.

M.I.A. for 88 years

Lost Cincinnati doughboy to be buried today in Arlington Cemetery ceremny

By Paul Duggan

Courtesy of the Washington Post

In a chapel at Aisne-Mame American Cemetery in France, the name of Private. Francis Lupo is engraved

along with those of U.S. troops from World War I who “sleep in unknown graves.”

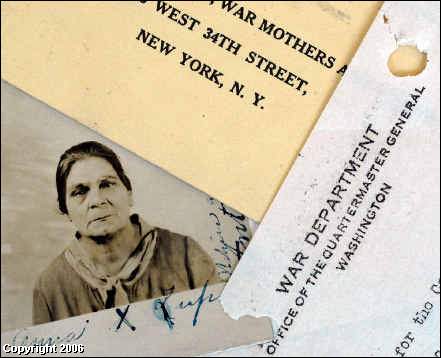

A photo of Anna Lupo, the mother of Private Frances Lupo, and documents on his death.

WASHINGTON – Missing in action, presumed dead.

And eventually he faded from living memory. His generation passed away, with everyone who loved him, everyone who mourned him. Time rendered him faceless. He was just a name, one of hundreds chiseled in limestone in a cemetery chapel 4,000 miles from home.

LUPO FRANCIS PVT 18TH INF

1ST DIV JULY 21 1918 OHIO

A lost doughboy.

But now he is found.

Discovered by chance, unearthed in 2003 by archaeologists looking for ancient remains, Private Francis Lupo of Cincinnati, Ohio, has returned from the front at last, nearly 90 years after boarding a troop ship for France. Today, the Army will bury him again, this time with honors at Arlington National Cemetery, laying to rest possibly the longest-missing U.S. soldier ever recovered and identified: a ghost of World War I.

Lupo, killed at 23, most likely on his first day in heavy fighting, will get a fine Arlington send-off, with all the Army’s Old Guard solemn pomp: a horse-drawn caisson; a bugler; rifle volleys; a tri-folded American flag for his next of kin, a niece born 15 years after the armistice.

There’s great solace in that Arlington tradition, if not always for a slain soldier’s family, then for the military, comforted and reaffirmed by the enduring ritual. Perhaps no one alive now met this private; but he fell in uniform, and that’s what matters to the Army.

The niece, Rachel Kleisinger, of Florence, Ky., says she is probably the only surviving descendant of Lupo’s who knew he existed before his remains were found. And she’ll be the only person at the service who knows for sure what he looked like, from a photo she saw as a girl.

His battalion was pushing through wheat fields in northern France under German artillery and machine-gun fire that summer Saturday when Lupo was killed. Hastily buried in a shell crater, he was left behind with the rest of the dead as the battalion kept up its advance.

The grave, a few feet deep, one of many in those fields, was meant to be temporary. But war is chaotic and infinitely cruel. What happened to Lupo in combat, what became of his body, was never officially recorded.

Maybe the soldiers who buried him were killed an hour later. Or the next morning. A lot of battlefield graves were lost that way in the carnage. No one will ever know.

Lupo wasn’t alone in that shallow grave. A second doughboy had been buried with him. Their bones were mingled. Small remnants of two uniforms were found, along with bits of gear. No identity tags turned up. But the dirt yielded pieces of a wallet, the name “Francis Lupo” embossed in the brittle leather. Anthropologists and other specialists confirmed for the military that Lupo’s bones were among those in the hole. But who was the other poor fellow?

Unknown. What’s left of him is boxed on a lab shelf, a number without a name.

Lupo’s service record and a lab report describe a fireplug of a man – muscular, 5 feet tall, maybe shorter, with olive skin, black hair and brown eyes. His Sicilian-born mother, who grieved his loss terribly until she died in 1949, kept a big picture of him in her parlor, a portrait of her son in uniform with an American flag.

Kleisinger, 73, recalls staring at it as a child, an old photo even then.

“Such a handsome boy,” she says. “And very proud, I think.”

It’s long gone, that photo, and the military knows of no other. Still, pieces of his story survive, deep in archives and libraries – footprints of a lost doughboy whose short life mirrors a big part of the American experience.

He grew up in a polyglot neighborhood near Cincinnati’s riverfront, one of eight siblings born to Sicilian immigrants, his father a laborer. They lived in tenements before the war. Lupo later told the Army that one of his occupations as a young adult was “pugilist.” He said his last year of schooling was the fifth grade. “For one of his station he presents average intelligence,” a military doctor noted.

When rabid patriotism and war fever swept the country in 1917, he was an $8-a-week “supply man” for the Cincinnati Times-Star, delivering papers to newsboys. He went off to France with a confident generation, young men eager to fight “the Hun” – until they met the horrific reality of modern, mechanized slaughter on the Western Front.

The war had been raging on several fronts for three years, with millions dead, when the first Americans landed in France. After a months-long buildup, the doughboys began fighting in large numbers in major battles in the spring of 1918 – just as Lupo reached the front – and eventually helped break a murderous stalemate that had consumed a generation of European youth in the trenches. By autumn, the war was over.

The price for the United States: about 116,000 dead, roughly 53,000 in battle, most of the rest from illnesses, mainly influenza. Tens of thousands of them were immigrants or, like Lupo, the first generation of their families to be born in this country. Nearly 4,500 of those killed are unaccounted for.

The limestone chapel stands in the countryside about 60 miles east of Paris by a forest called Belleau Wood, its tower rising 80 feet above the headstones of more than 2,200 doughboys killed nearby. No one who knew them visits anymore.

Soft light through stained-glass windows bathes the chapel’s vestibule, where an inscription tells of 1,060 other men, their names recorded on the walls, American soldiers of the World War who fought in the region and “sleep in unknown graves.”

Lupo’s name is chiseled on a tablet to the right of the marble altar. His mother, Anna, traveled from Cincinnati to see it in the summer of 1931, a month-long round trip by train and ocean liner, a government-paid pilgrimage for Gold Star mothers. She was about 60 then. Her husband had died of pneumonia in 1922. She spoke no English.

Years later, it was plain to Kleisinger that the journey did nothing to ease her grandmother’s suffering.

“Sweet” had always been one of Anna Lupo’s pet names for Francis. “Ducce” was how she said it in her Sicilian dialect, or “sciue” when she used Neapolitan. In her late seventies, near the end of her life, a small widow sitting alone in a room, she sometimes would begin to cry.

“We’d say, ‘Grandma, what’s wrong?’ ” Kleisinger recalls. And Anna Lupo, still weeping, always in black, would stand, open a window and call out.

Sciue-ducce! … Sciue-ducce!

“It was like she was telling him, ‘If you can hear me, come home,’ ” Kleisinger says. “You couldn’t stop her. The best thing we could do was just leave her alone.”

Lupo started working for the circulation office of the Times-Star in 1913, when he was 18, and before long, the bundles he was delivering were filled with dispatches from vast fronts, telling of foreign armies clashing.

In August 1914, German divisions marched into northern France but stalled, and soon the combatants dug in, stalemated in elaborate trench lines from the English Channel to the Swiss border.

Year after year, the war brought epic bloodletting to scorched towns and river valleys: the Marne, Ypres, Verdun, the Somme. In time, Americans grew to revile the Huns depicted in British and French propaganda. Germany’s intrigues in Mexico threatened U.S. security, and its submarine attacks on commercial shipping cost American lives.

Even in heavily German-American Cincinnati, crowds of men cheered and waved their hats when Congress declared war April 6, 1917. Bands played in the streets. Men ages 21 to 30 nationwide were required to register for the draft at their polling places June 5, and nearly 10 million did, among them Lupo.

“It was a gay and mirthful throng fired with excitement,” one paper said of the thousands of Cincinnatians who gathered to wish the young men well. Lupo claimed no exemptions; he reported to his registrar that he was 22, unmarried, unencumbered and fit to serve. The press gushed: “The next step is preening the American eagle for his overseas flight, as straight as this bird of hooked beak and strong talons can wing it.”

Lupo’s draft letter came in September, and he reported for a physical.

As a boy, Lupo had been severely sick at least eight times, racked by some of the suite of illnesses that often proved fatal to children in his era: diphtheria, whooping cough, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever. The bouts left tiny ridges on his teeth that anthropologists would notice a century later.

The typical draftee was just under 5-foot-8. Lupo’s height was listed as 5 feet at a time the Army’s minimum requirement was 5-foot-1. Anthropologists think he was 4-foot-10. But no matter. America needed fighting men. “Excellent muscular,” a doctor noted. He was inducted Oct. 3, 1917, and went off to fight in size 5 1/2 boots.

The making of Lupo the soldier began with a winter at Camp Sherman, Ohio, where he received his basic training. Then, with other new soldiers from the camp, he boarded a troop train for New Jersey. Eventually they crowded onto a ship in Hoboken, and, after a convoy was assembled, they got underway March 14, 1918, off to kick Kaiser Bill.

From the French port where he landed 12 days later, Lupo traveled inland, almost certainly by rail, jammed with other doughboys on a “forty-and-eight,” a boxcar built for 40 men or eight horses. Within a day or two, lugging his haversack, he got off at a training depot, where he commenced drilling again and learning more about the trenches.

Finally, on June 2, he went into the line northeast of Paris, joining E Company of the 18th Infantry while the regiment was positioned near the battered village of Cantigny. The 18th, bloodied a few days earlier in fierce fighting to hold the town, needed replacements.

And here came Pvt. Lupo, in clean breeches and tunic, ready to fight the Germans. Raised by devout Catholic parents, he carried a prayer card in his brown leather wallet. It bore the image of a deceased French nun who would soon be canonized, St. Therese of Lisieux. And it bore words.

“I will spend my Heaven in doing good on earth.”

June passed quietly for Lupo’s new outfit in a defensive sector near Montdidier, with some shelling, some trench raids back and forth, but no heavy fighting.

Probably no one briefed him on the big picture: After a long buildup, the Army was preparing for its biggest offensive operation since arriving in France, an attack on a German salient, a bulge in the line south of Soissons. The French-led assault would include the U.S. 1st Infantry Division, of which Lupo’s regiment was a part.

His 2nd Battalion, with 938 men, was held in reserve July 18 as two American divisions and tens of thousands of French troops began the attack, including a push through vast, open crop fields. The advancing soldiers could see far across a landscape of deep ravines, low hills and stone farmhouses, a broad terrain studded with German artillery and heavy machine guns.

A Marine Corps officer fighting with the Army’s 2nd Division recalled the battle’s second day, July 19, in his diary:

“Wallace, hit in the legs, went down in the short wheat. … Overton was hit by a big piece of shell … his heart was torn out. … A man near me was cut in two, others would stand … then fall in a heap. … In a shallow trench … I found three men blown to bits, another lost his legs, a fifth his head. At one end of the trench sat a crazy man who with a shrill laugh, pointed and said over and over, ‘Dead men, dead men.’ ”

On the third day, July 20, the doughboys of Lupo’s battalion joined the battle. After passing the ruined village of Missy-aux-Bois, they were pushing east across hundreds of acres of low wheat, struggling to reach the bombed-out town of Ploisy.

He fell amid the acrid stench of manure and cordite. His skeletal remains are long past telling what killed him: a shell blast, a gust of machine-gun fire. The soldiers put him and the other man in a crater out there between the villages and kept moving.

Among the 2nd Battalion’s 44 dead, wounded and missing that day was another young Ohioan, Arlow Griffith, a private in G Company. “I identified him after he was killed,” a sergeant wrote, “and owing to the fact that we had to advance, I don’t know where he is buried.” Griffith’s name is chiseled in the chapel limestone with Lupo’s.

Not until the next day, Sunday, July 21, was Lupo recorded as missing. Three weeks later, back in Cincinnati, his name was in all the papers, one among dozens in long columns of tiny print, a new casualty list from overseas.

By then, Anna Lupo, whom he always listed as his next of kin, had received a wire at her home on West Ninth Street, a few lines of teletype from the War Department.

“Deeply regret to inform you …”

The campaign, eventually known as the Second Battle of the Marne, was a victory for the Allies. After more big battles, and many thousands more casualties, the war ended in November.

The fields around Soissons stayed mostly farmland through the decades, with industrial buildings here and there. Because ancient remains have been found in the region, the law requires an archaeological survey before new construction takes place.

That was how Lupo and his fellow doughboy turned up in 2003.

The French archaeologist who determined how the men had been buried found no corroded weapons or helmets. What he unearthed, besides the bones, were scraps of clothing and boots, some uniform buttons, bits of a gas mask, a rusted canteen-cup handle and other decayed pieces of gear. There were personal items, too: the stem of a tobacco pipe, a rusted straight razor, a warped No. 2 pencil, a comb with seven teeth missing.

And Lupo’s wallet.

In 2004, the bones and artifacts were delivered to the Defense Department’s Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command in Hawaii. Anthropologists, historians and other specialists there work to find and identify missing U.S. military personnel, almost exclusively from World War II on. None had dealt with a doughboy before.

After the lab finished its work last fall, the Army searched for next of kin, eventually finding Kleisinger in Kentucky. She is a daughter of Lupo’s youngest sibling, Rose, long deceased. Rose was 7 when her brother Francis went off to Camp Sherman.

So Kleisinger – 4-foot-11 – will get the tri-folded flag at Arlington. No old men of E Company will be there, no aged veterans of Saint-Mihiel or the Meuse- Argonne. Of the 4.7 million Americans in uniform during Lupo’s war, all but a dozen or so are dead.

And his mother, in her grave 57 years.

“I used to go to church with her and help her light the candles,” Kleisinger says of Anna Lupo. “She would always ask the Blessed Mother to please bring him home. And I kept telling her, you know: ‘He can’t come home, Grandma. He’s gone.’ But she could just never accept it.”

27 September 2006:

Private Francis Lupo, a young Cincinnatian killed in a frightful World War I battle, was buried with full military honors Tuesday at Arlington National Cemetery.

For almost nine decades his remains and those of another soldier had rested in a French wheat field, unmarked and unknown to their armies or their families. The archeologists who discovered their bones speculated that the soldiers’ bodies had been thrown into a shell crater and hastily covered over during the Second Battle of the Marne – an encounter that killed or wounded 30,000 Americans alone in the span of a month as Allied armies repulsed a German attack and launched an offensive aimed at ending the torturous trench warfare that had claimed an entire generation of European men.

In the fields where Private Lupo fell more than 3,200 other Americans were killed – slightly more than the number of American soldiers who have died to date in Afghanistan and Iraq over the last five years.

It’s healthy, we think, that this young soldier, whose death was so anonymous, is now getting such widespread attention.

He was, judging from the marvelous accounts that have surfaced in recent days, an ordinary man, one of nine children born to Sicilian immigrants who lived on 9th Street near downtown Cincinnati. He dropped out of school in fifth grade and went to work; when he was drafted in 1917 he was working for the Cincinnati Times-Star delivering bundles of papers to newsboys.

He never married. His relatives have long since passed away. The only one known to have a personal connection to the family, Rachel Kleisinger of Florence, Kentucky, told reporters that Lupo’s mother, Anna, never got over the loss of her son. After the dread telegram came announcing that her son was missing and presumed dead, after she had traveled to France and seen her boy’s name carved into the wall of a chapel honoring the war dead, Kleisinger said, Anna Lupo would sit alone in her room, weeping and calling for her son to come to her.

All told, World War I killed an estimated 10 million people. It was a mechanized bloodletting that could have been avoided. It was said at the time to have been the war to end all wars. Instead it set the stage for an even more horrific world war that engulfed not just Europe but much of Asia and killed more than 50 million people.

These numbers help put our current conflicts into perspective.

But we don’t know, we can’t yet know, where the wars of our generation will lead us. Will they prove to be limited in scope, akin, say, to Korea and Vietnam? Or is this the early stage of a wider battle, one that pits the West against all Islam, or one perhaps that will see the great powers locked in an all-out fight for control of the world’s oilfields?

What does all this have to do with Pvt. Francis Lupo?

Ultimately it is our military that is called to execute the decisions our political leaders make. It is our military that most intimately understands the human cost of war. This is why the armed forces place such importance on the proper burial of their dead, why, 88 years after a 23-year-old Cincinnatian’s body was shoved into a shell crater and covered with dirt during the heat of battle, the military would go to such lengths to identify his remains.

The human cost is also the reason we should all remember Private Francis Lupo – and his mother weeping for the son taken from her by the savagery of war.

Family presented with memorabilia from fallen WWI soldier

By MORGAN C. MOELLER

Courtesy of Hernando Today

Published: November 13, 2006

All was quiet in the Panno home Monday afternoon.

Joe Panno, 74, sat listening intently to the story of an uncle he never knew.

Francis Lupo disappeared 14 years before Joe was born. All Joe knew of him was what he could make of his Italian grandmother’s broken English and the occasional story told by his mother.

The story he was told went something like this: Francis went off to fight during World War I, and he never came back. The family assumed he had died, but no one was sure how or where. There was never a burial. Francis never received a 21-gun salute.

On Monday, Paul Bethke, of the Army’s Casualty and Mortuary Affairs Operative Center, helped Joe fill in the blanks.

Eighty-eight years ago during World War I, Army private Lupo was a member of the Company E, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. His unit fought in the French-American attack on the Germans near Soissons, France, which later became known as the Second Battle of Marne, Bethke told a living room full of great-nieces and nephews. American forces suffered heavy losses in the fight. Of the 12,288 in that infantry, two-thirds died. Francis was among the 8,076 enlisted men who were listed as a casualty — either wounded, missing or prisoners.

Despite the losses, the battle became known as the turning point in the war, Bethke said. It halted and reversed the final German advances toward Paris.

After the war was over, none of the returned prisoners of war could remember Francis being detained. No one could remember where or how he may have been killed.

The Lupo family never knew what became of their 23-year-old son. Born of Italian immigrants, Francis left behind three brothers and three sisters. Francis’ mother, Anna, and all six of his siblings died long before the mystery was solved.

Piecing the puzzle together

Then, three years ago, a French archaeological team was conducting a survey for a construction project when they discovered human remains, a boot and a wallet with the name Francis Lupo embossed on it. The French handed the items over to U.S. officials for analysis.

The Joint POW/MIA Missing Personnel Office got to work sifting through the evidence they had, Bethke said. The wallet embossed with Francis’ name was the most outstanding clue, and that’s where the search began.

Family members flipped through the pages of a booklet outlining the data, following along as Bethke talked. One page showed pictures of the wallet, partially deteriorated, but intact for the most part. Francis Lupo was embossed in the lower right hand corner.

From there, the pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place, Bethke said. Scientists guessed that the deceased was between 4-foot-8 and 5-foot-1 based, on the size of the bones found. Francis’ height was listed as 5-foot in military records.

The person’s weight was estimated at 122 pounds. Francis’ weight was 122.5.

The boot found was a size five and a half. All the facts appeared to line up.

Another scientist went to work on examining the jaw bone found. The scientist found evidence of a cavity, indication that he was either ill as a child or malnourished and that one of his teeth had been pulled. The dental records appeared to match up as well.

Bethke continued to explain that they still didn’t know how Francis died. There was no evidence of trauma in the skeletal remains, he said. He added that Francis was killed in an area of heavy artillery fire. It’s possible that a bullet lodged in muscle rather than bone.

A missing link

When they had determined with some certainty that it was Francis, they tried to get in touch with the family. Genealogists worked out a family tree so that Army representatives could get in touch with the oldest living relative. That person would be considered next of kin and therefore responsible for deciding on funeral arrangements and receiving military honors and memorabilia.

Army representatives first called Frank Panno, Joe’s brother. He had died nine days earlier, and his widow was still in a state of shock. She doesn’t even remember the call coming in.

Then they moved down this list. Army representatives called Rachel Kleisinger, a distant cousin. Rachel didn’t tell them of any other relatives. And Joe, for some reason,wasn’t on the list.

Rachel was designated next of kin. The Army held a funeral on Sept. 26, attended by an assortment of dignitaries, including representatives from the French armed forces. The mystery was finally solved. Francis finally had his 21-gun salute.

But the story didn’t end.

‘Fate’

Joe’s daughter, Kristina, was running late for her lunch break a week before the funeral took place. When she finally hopped in the car, she turned to the Cincinnati news talk show she listens to and caught the tail-end of a story about a World War I soldier. The man’s remains were found in France, and he was to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery the following week.

“Welcome home, Francis Lupo,” the announcer said. “Welcome home.”

Kristina froze. Francis Lupo? That was her great-uncle. She called her father who lives in Spring Hill.

Yes, Joe said. That was his uncle Francis — his mother’s brother. But he hadn’t heard a thing about it. Kristina was fuming. She called the radio station. Then the Red Cross. Then Arlington itself.

On Tuesday, Sept. 26, the burial was to be held at the national cemetery. It was Monday, and Kristina hadn’t heard a word. The day of the funeral, she left one more message, then gave up. She could hear the disappointment in her father’s voice.

“That destroyed me,” she said. “My dad doesn’t say any of that, but you can hear it in his voice.”

A rude awakening

At 3:30 a.m. on Sept. 27, Michele Simon’s 5-year-old daughter woke up crying. Michele picked her up and carried her to the couch where she turned on the TV.

The screen flickered with ABC’s World News. She watched as she waited for the little girl to fall back asleep.

The anchor was talking about a soldier who was buried at Arlington National Cemetery the day before. His remains were identified through some new system the U.S. Department of Defense was using. On the screen, they flashed a picture from an article in The Washington Post.

Michele barely stifled a scream. The woman she was looking at on the screen appeared to be her grandmother — or someone who could have been her twin. The man they were talking about was her great-uncle, Francis Lupo.

She put her daughter back in bed and called ABC’s local news desk. They directed her to a New York newsroom. A producer came on the line and told her she would have to call back during the day.

Michele couldn’t sleep. She waited for daylight, drank coffee, got the kids off to school and drove back to her Spring Hill home. The Tampa Tribune was laying in her front yard when she got back. In the world news section she saw an Associated Press article about her great-uncle. There was a contact name in the paper — Larry Greer, public relations at the Pentagon.

Michele, aka Joe Panno’s niece, dialed the number.

Closing the chapter

On Monday, Bethke apologized for the mix-up. Joe’s name simply didn’t appear in the genealogy reports.

Joe said he only wished he knew sooner that the government didn’t have a record of him.

“I wish I would have known that when I was younger!” Joe said. “I wouldn’t have had to pay any income taxes!”

Because of procedures governed by law, Joe did not receive the flag and medals presented to his distant cousin at the burial. But Bethke presented him with a small, velvet pouch that held several bullets from the 21-gun salute. He also gave the family booklets explaining the identification process and CDs with photos of the service.

Remains from a second person were also found when Francis’ were discovered. In the future, Joe will be the family’s representative if the Army holds a group burial.

Although Joe initially said he wished Francis was buried at the family plot in Cincinnati on Monday, he was happy.

“I’m satisfied,” Joe said. “Let’s just put it that way.”

For other family members, like Francis’ great-nephew Tony Panno, it was the closing of a chapter.

“That was always a missing chapter,” Tony said. “We could never close that chapter, and now we can. We are very proud. We are very proud.”

The remains of Private. Francis Lupo, arrive at Arlington National

Cemetery, Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Rachel Kleisinger,arrives at the military burial of her uncle, Private Francis Lupo, at

Arlington National Cemetery, Tuesday, September 26, 2006

The remains of Private Francis Lupo are set for burial at Arlington

National Cemetery, Tuesday, September 26, 2006

U.S. Army soldiers honor World War One soldier Army Private Francis Lupo, of Cincinnati, who

was finally buried in Arlington National Cemetery after his remains were found in 2003 after dying in World War One

in France nearly 90 years ago, September 26, 2006

U.S. Army soldiers honor World War One soldier Army Private

Francis Lupo at Arlington National Cemetery

US Army Honor Guard fold the flag that covered the casket of US Army Private. Francis Lupo of the

18th Infantry, 1st Division during military honor burial services at Arlington National Cemetery

Rachel Kleisinger, center, accepts the American Flag at the military burial of

her uncle, Private Francis Lupo, at Arlington National Cemetery, Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Army officer gives a folded U.S. flag to Rachel Kleisinger, (seated), a

descendant of World War One soldier Army Private Francis Lupo

French military representatives console Rachel Kleisinger (seated), a

descendant of World War One soldier Army Private Francis Lupo

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard