Fulton P. Lanier

Captain, U.S. Army Air Forces

0-430592

Air Transport Command

Entered the Service from: North Carolina

Died: January 18, 1946

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines

Awards: Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster

Fron a contemporary press report: January 1998

Captain Fulton Lanier comes home

Almost 54 years to the day after his plane crashed in the Himalayas, a Buies Creek hero gets full military honors at Arlington.

Captain Fulton Pershing Lanier once was lost, but now is found. Lanier, a young man from Buies Creek who became a World War II pilot, will be laid to rest with full military honors today after a long journey home from the Himalayan glacier that held his remains for so many years.

Lanier’s burial at Arlington National Cemetery will complete a homecoming that brings peace to his relatives and redeems a government’s promise to the soldiers it sends to war.

Lanier “flew the Hump” during the war, guiding his noisy, four-engine C-87 Liberator over the Himalayan Mountains to bring food, ammunition and medicine to Chinese nationalist troops fighting on the side of Allied forces against the Japanese Imperial Army.

On January 31, 1944, Lanier and four crew members left their base in Jorhat, India, for a supply flight to China. It was a run Lanier, 27, had made two dozen times before. Archibald Doty Jr., another pilot who flew the route on the same day, would later report rain, sleet and snow in his flight log, along with “St. Elmo’s fire,” the flamelike electrical discharge sometimes seen from wingtips during electrical storms. “Like a monsoon, but cold,” Doty wrote.

Lanier and his crew landed safely in Kunming, China, north of the mountains, and unloaded their supplies. They began the 4 1/2-hour return flight to Jorhat about noon. The plane never returned to its base. The five fliers were listed as missing and presumed dead. At the war’s end, they were declared dead.

Back in Harnett County, Bill Lanier, Fulton’s nephew, was 11. He and other family members — Fulton’s three brothers, two sisters, their parents — accepted the military’s conclusion. But doubts lingered. “There was always the question — was he captured?” Bill Lanier, now a pharmacist at Eckerd Drugs in Buies Creek, said last week. “Was he shot down?”

Later in 1944, Fulton Lanier received a posthumous promotion from first lieutenant to captain. In July 1994, a half-century after their uncle’s disappearance, Bill’s half-brother, District Judge Frank Lanier, got a call from the Pentagon. Tibetan hunters had stumbled upon the wreckage of the C-87 and some human remains high in the Himalayas. Fulton Pershing Lanier was found on a glacier at an elevation of 14,000 feet. “It was such a total surprise,” the judge said. “I never dreamed of getting such a phone call.”

Military sleuths

In Hawaii, John Webb, a retired lieutenant colonel, had learned of the Tibetan discovery a few months earlier. Webb is director of the Army Central Identification Laboratory, established in 1973 in Thailand as a small operation to locate and identify remains from the Vietnam War. Webb heads a staff of 177 today, including 19 anthropologists and two forensic dentists. With an annual budget of $5 million, he sends dozens of crews around the world each year to find, identify and repatriate the remains of American servicemen.

Webb’s teams have floated the Amazon, hacked through jungles in Laos and Cambodia, scaled cliffs in Europe. Tibet, though, is another matter. It is home to some of the highest human settlements on Earth. The Himalayas are among the most rugged of all mountain ranges; their crown, Mount Everest, is the world’s tallest. Tibet is also a disputed region, controlled by China against the will of many of Tibet’s 1.4 million people. China is a nuclear superpower, one that has strained relations with the United States. In the 16 years Webb has worked at the lab, the discovery of Lanier and his crew is the only such find in Tibet.

The news came to Webb from the highest levels of the Pentagon. When Tibetan hunters discovered the wreckage in November 1993, they notified local Chinese authorities. The central government dispatched a reconnaissance crew, which photographed the wreckage, made a videotape and took some of the remains to Beijing. A wing, shorn from the body of the plane, displayed a U.S. Army Air Corps star insignia on a blue background.

The Chinese informed then-Defense Secretary Les Aspin of the find. When Webb received his orders to investigate the Chinese find, he sent five people to Beijing. They brought the remains to Hawaii. Technicians traced the serial number from an engine part at the wreckage site. Using military manifests, they learned the names of the five airmen assigned to the plane for its last recorded flight — Flight 862, on January 31, 1944, the date Lanier had disappeared. Lanier was one of the five names on the manifest. The others were First Lieutenant Frank M. Ramos, the co-pilot; Corporal Joseph Petrella; Private First Class Eugene E. Beebe and Private First Class Bartholomew R. Giacalone.

DNA tests on the remains brought from Beijing showed that three of the five missing soldiers had been found. So, in September 1994, Webb dispatched another crew, to the crash site itself. The Chinese, wary, allowed Webb to send only three people. After a grueling three-day trek and painstaking archaeological work at the site, the team found more remains. In that cold place, the remains and wreckage had survived remarkably intact. After 50 years, meal tickets were still legible. An embroidered shoulder patch held a scrap of khaki fabric. The searchers also found the first lieutenant’s bars from Lanier’s uniform.

Soldiers’ souls

The U.S. military’s concern for its dead dates from the Civil War, when Union and Confederate commanders hired undertakers to travel with their troops, identify and embalm fallen soldiers and arrange for transport of their bodies home to their families.

In 1864, Quartermaster General of the Army Montgomery Meigs began efforts to bury soldiers on the grounds of Arlington House, the former estate of General Robert E. Lee, and it became the official national cemetery in 1883.

After World War II, the Pentagon set up temporary labs around the world to identify soldiers’ remains, and it ran a lab in Japan for several years after the Korean War. But the ambitious operation today sprang from the large number of soldiers lost in action in Vietnam.

“Those of us here that do this job see it as something we owe each individual,” said Webb, who served in Vietnam. “We often talk about caring for our soldiers. How much more caring can you be than recovering their remains and returning them to their homeland and their loved ones?” Thomas Holland, scientific director of the lab, said he is often struck by a poignant feeling of “there but for the grace of God go I” as he looks through the case files of the soldiers he is trying to identify.

Allan Millett, a professor of military history at Ohio State University, said no other country invests near the amount of effort, manpower, money or time the United States puts into finding its fallen soldiers. “It reflects a degree of concern and sense of obligation on the part of the military establishment and the Congress — which has to make the money available — that honors every serviceman,” Millett said.

Prophetic name

Fulton Pershing Lanier was the youngest in the family and small at birth, so his family called him Runt — a term of endearment some of his relatives still use. But the boy grew into a man who stood more than 6 feet tall. After playing football in high school and at Lenoir-Rhyne College, he enlisted in what was then called the Army Air Corps in 1941 and earned his pilot’s wings.

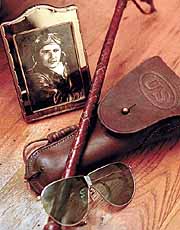

Lanier did a tour of duty in Asia, then served in Texas as a flight instructor. He volunteered to return to he Far East. His last visit to Buies Creek was in June 1943. Bill Lanier, then 9, remembers his uncle’s showing off his equipment, especially his .45-caliber pistol. To demonstrate his good aim and steady hands, he shot the glass balls from weather vanes on some houses in town. Fulton Lanier joked to his family that flying supply routes to China couldn’t be more dangerous than instructing novice pilots. Seven months later, in the fog and the freeze of the Himalayas, he made his final flight.

Twenty relatives of Lanier plan to attend the burial today. They will come from Buies Creek, Erwin and Durham, as well as South Carolina, Delaware and the District of Columbia.

The remains of all five members of the C-87 crew will be buried in a single steel casket. After a service led by a military chaplain at nearby Fort Myer, the coffin, draped by an American flag, will be carried to the grave site. Seven soldiers will fire seven rifles into the air, three times in succession. The flag will be removed from the casket, folded and presented to a cemetery official to join the rotation of banners that fly, one day for each flag, over the Tomb of the Unknowns. Other flags, folded, will be touched to the coffin, then given to a member of each family. As the casket is lowered into the ground, a bugle will ring out.

“The families usually get through the volleys, but the sounding of ‘Taps’ is when it really hits home for most people,” said Pentagon spokeswoman Shari Lawrence.

Lanier’s parents may have had a premonition that he would be a soldier. When he was born in 1917, the United States had just entered World War I and General John Joseph Pershing led the first American troops ever sent to Europe. For his middle name, Fulton Pershing Lanier received the surname of the great general. And when Lanier is finally buried today, 54 years after his death, his last resting place will just a few steps from the grave of Pershing at Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard