U.S. Department of Defense

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs)

News Release

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 150-03

March 25, 2003

DOD IDENTIFIES MARINES KILLED IN ACTION

The Department of Defense announced today the identities of seven Marines killed in action March 23 in the vicinity of An Nasiriyah, Iraq. Killed were:

Sergeant. Michael E. Bitz, 31, Ventura, California. He was assigned to the 2nd Assault Amphibious Battalion, 2nd Marine Division, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina

Lance Corporal David K. Fribley, 26, Lee, Flproda He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina

Corppral Jose A. Garibay, 21, Orange, California. He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, Camp Lejeune, No0rth Carolina

Corporal Jorge A. Gonzalez, 20, Los Angeles, California. He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina

Staff Sergeant Phillip A. Jordan, 42, Brazoria, Texas. He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina

Second Lietuenant Frederick E. Pokorney Jr., 31, Nye, Nevada. He was assigned to the Headquarters Battery, 1st Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Lance Corporal Thomas J. Slocum, age unknown, Adams, Colorado. He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina

Fallen Heroes Fund Steps In For Families Of Those Lost At War

OCTOBER 30, 2003

NY1’s Amanda Farinacci reports on the Fallen Heroes Fund, which provides financial assistants to family members of soldiers killed in Iraq or Afghanistan.

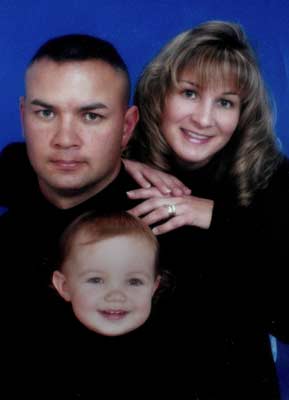

Four-year old Taylor Pokorney has practically memorized one of the last letters she received from her father, Frederic E. Pokorney.

The 31-year-old Lieutenant was killed in March during combat in Iraq, leaving Taylor and her mother Chelle behind to honor his memory.

He was the first Marine killed during Operation Iraqi Freedom to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

“It was the most beautiful thing,” said Chelle Pokorney. “My husband was a very proud Marine. We were there two years ago with, to see my grandfather. He’s buried there; he’s a colonel in the Air Force. And Fred told me, ‘Chelle, I want to be buried here and I want you to be buried on top of me.’ So I hold that in my heart that I did the right thing for him.”

Fred and Chelle met eight years ago at the gym while she was attending nursing school. He was stationed at a base in Washington State.

Described as a gentle giant, Fred was a man obsessed with his daughter and passionate about his career. They moved to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. In January, Fred left for Iraq.

He died two months later.

“It was horrifying,” Chelle said. “It was the most horrifying thing you could ever go through and I hope nobody has to ever go through it. Unfortunately, this is not the reality of the world we live in.”

The reality of her new world has not yet set in for Chelle. She’s since moved from North Carolina to be closer to her family.

The government provides some benefits to surviving families. According to the Department of Defense, the immediate death benefit for a member killed in the line of duty is $6,000, $3,000 of which is taxable.

Families can stay in military housing for six months at no cost. Members that have life insurance policies must wait for them to kick in, but officials say while most sign up for the policies when they’re first enlisted, many cancel the policy shortly thereafter because the money is taken out of their paycheck.

And that’s where the Intrepid Fallen Heroes Fund comes in.

Set up by the Fisher Family and the Intrepid Foundation, the fund helps those left behind transition financially. It’s also a way for the public to say thanks.

“Fallen heroes was our way of helping the military families,” said Arnold Fisher, a creator of the Fallen Heroes Fund. “The government really should be doing this but I don’t want to get into that. This is the public’s way of showing military families that we care about them.”

The fund takes donations from private companies, individuals, and corporations, sometimes matching them dollar for dollar.

The goal is to send each family with dependents $10,000. They’d like to raise that to $25,000.

In just the last four months, the fund has helped more than 275 families of troops killed in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“After the death of the loved one, they have family around them and friends around them,” Fisher said. “And then suddenly it stops and they’re alone, and then when they get a letter from us and a check to show that we care. It gives them renewed hope.”

“Money definitely helps the situation in a tragic time like this,” Chelle said. “It can help take some of the burdens off when you’re feeling like you’re grasping for anything. When somebody gives you something and helps and reaches out to you, it gives you hope for the future of what your husband gave his life for.”

While the money does make life easier for widows like Chelle, no amount of money will ever make up for her loss.

“Every time I see a red truck or every time I see a tall man that’s about his height, because he was very tall, I hope someday that he might come through that door,” she said. “So I don’t know if that reality will ever set in, because when you have the love of your life and the father of your child, I don’t know, you can ever let go of that. I think the pain might get easier and you don’t cry as much, but I don’t know if you can ever. It’s so soon. They say time heals, but I don’t know.”

Pentagon workers do not have to go far to be reminded of the price of war. On a grassy eastern slope of Arlington National Cemetery, within view of the massive military headquarters, soldiers killed in Iraq are being buried.

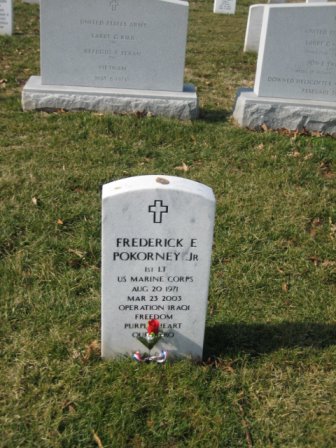

Nevada Marine Lieutenant Frederick Pokorney was laid to rest there Monday. The simple white marble headstone that will mark his grave has not yet arrived. It typically takes a few months for cemetery workers to place the markers. They are busy.

In a typical week, about 25 people are buried in the hallowed burial ground outside Washington. In 135 years, more than 280,000 servicemen and women and their spouses have been laid to rest on the 624 acres of rolling green Virginia hills.

Tourists at Arlington typically flock to the cemetery’s most popular draws: the eternal flame at John F. Kennedy’s grave site, the Iwo Jima Memorial on the Arlington’s north border, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

But the true power of Arlington — its ability to inspire awe for the sacrifice made by so many thousands — can also be found in a quiet walk along the endless rows of simple white headstones.

Consider just one of the marble slabs — the one that soon will mark grave No. 7861 in section 60. Last week 150 mourners huddled at that spot to honor 31-year-old Pokorney, who lived in Tonopah when he was a teenager. Standing aside the flag-draped coffin, Chaplain Commander Lewis Brown offered a simple benediction, “May he rest in peace.”

As part of a full-honors ceremony reserved for officers, six Marines in dress blues folded the flag into a tight triangle and it was presented to Pokorney’s wife, Chelle. She let their 2 1/2-year-old daughter Taylor hold it. As the two knelt by the coffin, the girl asked, “Where’s daddy?”

That question is only a glimpse into the story of sacrifice memorialized by a single stone. At Arlington, visitors can walk for hours along the perfect rows of grave markers, each with a story of its own.

And every day, more are buried. Fallen soldiers from Operation Iraqi Freedom are now joining veterans of the American Revolution, the Civil War, two World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam. The chilling notes of Taps and the sharp crack of three-round rifle volleys break the still quiet at Arlington two dozen times a day.

Lieutenant Pokorney was buried next to Army Captain Russell Rippetoe, killed by a car bomb that exploded at a U.S. checkpoint. On Wednesday Marine Captain Benjamin Sammis was laid next to Pokorney.

Back at the Pentagon Thursday, Rumsfeld sounded a note of caution, amid notable good news.

“The war is not over,” Rumsfeld told those gathered in the Pentagon’s auditorium. “We know that. There are still pockets of resistance, shots are still being fired and people will still be killed. And as we gather here people are still fighting in Iraq and elsewhere.”

Washington is full of monuments to democracy, independence and peace. Soon a new monument, an 18-inch marble tablet in Arlington’s section 60, will be raised to honor one sacrifice paid to maintain those ideals. It will read, “Lieutenant Frederick Pokorney USMC.”

May 2003:

This Memorial Day, a young widow and her 2-year-old daughter will visit Arlington National Cemetery and the grave of Marine First Lieutenant Fred Pokorney.

The three of them were building a life together before he was killed in an ambush in Nasiriya, Iraq, on March 23, 2003.

Now Chelle Pokorney has photographs, letters, memories — and the knowledge, secure in her mind, that her husband’s cause, to free the Iraqi people from Saddam Hussein’s rule, has triumphed.

“I hope they can have hopefully have a democracy or whatever they’re reaching for — freedom from turmoil, and the pain and suffering they’ve been going through,” she said just weeks after the Lieutenant died.

Her husband made the ultimate sacrifice for his country. Now, she is struggling to provide a future for their daughter, Taylor.

“I just hope I’m doing the right thing for his little girl,” Pokorney said.

The house the couple bought together outside Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, has to be sold, because even with Social Security and military benefits, there’s more money going out than coming in.

“I’m gonna get through this. It’s never gonna be OK. It’s never gonna be the same,” she said. “My life’s been taken from me, you know. Fred was our life, and we have to make a new life, but we can do it, and we can always have his memories.”

Some of her most precious memories are the letters he wrote like this one, one of the last he addressed to his young daughter:

“Are you taking care of Mommy? How is she doing? I know you’re doing your best to help her with everything. Please give her a big hug and kiss for me and tell her I love her, okay? I love you very much and miss you so much, my heart hurts. and I hope I get home to you and Mommy soon…and don’t forget me. Love always, Daddy.”

The wives of other Marines have tried to help console the young widow, but there are no easy answers. “Even when she calls me sometimes, I wish I had something to offer her to make a day go easier, to make a night go faster,” Amy Williams said.

Nights are tough, Pokorney says. That’s when the tears come, when Taylor’s asleep.

The last two months have seemed like an eternity of grief and emptiness, and Pokorney yearns for what she used to have.

“His big arms around me,” she said. “Just smelling him, just anything. You know it’s the simple things that you’re going to miss that are never going to be there again. And I’ll always be looking over my shoulder to see if he’s there.”

14 April 2003:

Shortly after Lieutenant Frederick Pokorney was buried Monday at Arlington National Cemetery, his 2 1/2-year-old daughter clutched the tightly folded flag that had just covered the dead Marine’s casket.

“Where’s daddy?”Taylor asked her mother, Carolyn Rochelle Pokorney, as the two knelt beside the casket for a final goodbye.

In a funeral service under a cloudless sky, Pokorney became the first Marine from Operation Iraqi Freedom to be buried at the cemetery in Arlington, Virginia – hallowed ground for the nation’s war dead. The 1989 Tonopah High School graduate was the first soldier from Nevada to die in the war on Iraq.

Pokorney, who was buried with full military honors, was killed in combat at Nasiriyah last month. Marine Lance Corporal Donald John Cline, 21, of Sparks was confirmed dead this weekend from wounds he received in the same battle.

During a Catholic Mass before the graveside ceremony, family friend Larry Mullins said the tall 31-year-old Pokorney was a”gentle giant”with a”real sense of compassion.”

“He was silent and strong,”Mullins said.”He was confident. He made you feel safe and secure.”

Mullins said Pokorney shouldn’t be forgotten. His bravery had made everyone proud.

“All in all it’s quite a life to celebrate,”Mullins said.”We won’t see a flag … without thinking of the sacrifice he made.”Well done, Marine. Semper Fi.”

About 150 mourners gathered to remember Pokorney, including a number of Marines. Among others paying tribute was the man Pokorney considered his adoptive father, former Nye County Sheriff Wade Lieseke. Sen. John Ensign, R-Nev., and Rep. Jon Porter, R-Nev. also attended.

Six horses drew the caisson carrying the flag-draped casket to Section 60, grave No. 7861 of the cemetery. A 25-piece Marine band and full honor guard marched in step behind.

A seven-man rifle team fired a traditional three-round volley and a bugler played Taps.

Marine Brigadier General Maston Robeson presented the folded flag to Pokorney’s wife.

Pokorney is survived by his wife and daughter, who live in Jacksonville, North Carolina, near Camp Lejeune, where Pokorney was stationed. He had been assigned to the Headquarters Battery, 1st Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade.

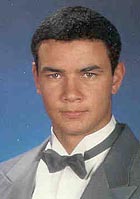

As a teenager, Pokorney lived in Tonopah, Nevada, a small mining town midway between Las Vegas and Reno. He lived with Lieseke during part of his high school years after his mother died and his father left town to find work.

Lieseke considered Pokorney a son. One of the last letters Pokorney wrote arrived at Lieseke’s home three days after the Marine died March 23.

Pokorney was a standout high school athlete in Tonopah, starring in basketball and football, and earning townspeople’s respect for his work ethic and self-reliance.

Several hundred turned out to remember him last month at a memorial service.

Pokorney graduated from Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon, before beginning his military service.

In an interview published Monday in the Daily News of Jacksonville, North Carolina, Pokorney’s widow said he told her before he left for the war, “No matter what, you have to keep on going and be Taylor’s best friend.”

Chelle Pokorney, 32, told the paper that she knew even as she embraced her husband a final time that she would have to make good on that promise.

She said the couple visited Arlington National Cemetery during a 2001 Memorial Day trip to Washington, D.C.

Her grandfather, an Air Force colonel, and her great-uncle, an Air Force general, are both buried at Arlington, and she recalled Fred Pokorney saying during that trip, “I want to be buried here. It would be an honor.”

Former Nevada resident and U.S. Marine Lieutenant Frederick Pokorney was buried with full military honors Monday morning at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Pokorney became the first Marine from Operation Iraqi Freedom to be buried at the cemetery, which is hallowed ground for the nation’s war dead.

The 1989 Tonopah High School graduate was the first soldier from Nevada to die in the war on Iraq. He was killed in combat at Nasiriyah last month. He is survived by his 2½-year-old daughter Taylor and wife Carolyn Rochelle.

The family lived in Jacksonville, North Carolina, near Camp Lejeune, where Pokorney was stationed.

Nation Buries War Dead at Arlington: 11 April 2003

By EILEEN PUTMAN,

Associated Press Writer

ARLINGTON, Va. – “Taps” is played here two dozen times a day, the notes as haunting and lonely as death, this hallowed ground’s abiding presence.

In Arlington National Cemetery, where the nation buries many of its war dead, horse-drawn caissons bear flag-draped coffins across a sea of white, military-issue tombstones. Buried here are those who served in Vietnam, Korea, the two World Wars, the Civil War, the American Revolution.

Young warriors barely past voting age and old retired vets lie next to each other, grave locations dictated more by logistics than military accomplishment.

“There is no rank structure in death,” says cemetery spokesman Tom Findtner, a line that sounds well-used.

More than 285,000 people are interred in the cemetery’s 624 acres, and 25 to 27 are added each day as the World War II veterans move through their 80s. Also buried here are former presidents, slaves, astronauts and members of Congress. During the height of the Vietnam War, as many as 40 funerals took place daily.

Funerals occur on weekdays, but after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks they were conducted into the evening and on Saturdays to accommodate victims from the plane crash into the nearby Pentagon.

If U.S. casualties in Iraq — 105 as of Friday — produce a large number of dead, the cemetery would again expand hours, said spokeswoman Barbara Owens.

Burial space is tight, and the cemetery plans to add 43 acres from adjacent military property. Lack of space has brought restrictions on who is eligible for in-ground burials. Relatives are interred in the same plot as their military personnel, where possible, and the cemetery encourages use of the columbarium, a facility for cremated remains.

Some of the dead, like Captain Russell B. Rippetoe, 27, an Army Ranger killed last week when a car bomb exploded at an Iraqi checkpoint, died in military action and came home to the honors accorded a war hero. He was the first U.S. military casualty buried here from the Iraq war.

As befits a place that has been burying heroes since 1864 — pre-Civil War dead were moved here after 1900 — the rituals are many and precise. One, the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknowns, is a major attraction for the 4.5 million tourists who stream through cemetery gates each year.

It was President Kennedy’s televised funeral that gave many Americans their first sight of the horse-drawn caisson, an open-air carriage that carried Kennedy’s coffin here from Washington, just across the Potomac River.

On Thursday, the caisson carrying Rippetoe’s casket was pulled by a team of six matched grays and escorted by a seventh ridden horse as a military band played “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and later, “America the Beautiful.”

Seven soldiers fired rifle volleys — the number of shots depends on the deceased’s rank. Then came “Taps” — played for all funerals — as a lone bugler stepped apart from the band and blew his solitary notes.

Rippetoe’s father, a retired Army officer disabled during Vietnam combat, sat in uniform with his wife Rita as the Army presented them with their son’s posthumous medals, among them the Bronze Star for valor.

The U.S. flag from their son’s casket was folded with military precision. A member of Rippetoe’s unit — 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment — presented it to Rippetoe’s father and knelt to recite, in a choked voice, the traditional words intended as solace for those left behind:

“On behalf of the president of the United States and a grateful nation, I present you with this flag as a token of the honor and faithful service of your loved one.”

Joe Rippetoe returned the salutes of his son’s fellow Rangers.

The family received a formal condolence card from a member of the Arlington Ladies, a women’s group that sends someone to every funeral. That tradition began in 1972 after an Army General happened on a burial with no mourners.

Even as Rippetoe’s funeral was ending, another was beginning. On a road nearby was parked a yellow backhoe, its driver waiting for the mourners to leave so the more practical tasks of burying the dead could go forward.

Rippetoe’s grave — No. 7860, Section 60 — is in an area where reminders of war’s cost in young lives are inescapable. Behind his is a grave with the remains of two soldiers killed when their helicopter was downed in Southeast Asia in 1971.

Next to Rippetoe lie Sergeant Joshua M. Harapko, 23, and Private First Class Shawn A. Mayerscik, 22, killed in a March 11 helicopter crash at Ft. Drum, N.Y. Their graves, like his, are too new to have received the tab-shaped white marble markers that are standard issue here.

Funerals are scheduled next week for more Iraq casualties, among them Marine Second Lieutenant Frederick E. Pokorney Jr., 31, who died March 30 in an ambush near Nasiriyah. Like Rippetoe, who coordinated artillery from the ground, Pokorney had a dangerous field artillery job.

Pokorney’s uncle, Richard Schulgen, said in an interview his nephew had wanted the honor of being buried at Arlington, where a grandfather and great uncle are also laid to rest. An enlisted man, Pokorney had recently become a commissioned officer and was proud of his service to his country.

“He was proud of what he was doing and proud of his family, a hardworking guy — the best guy you can ever know,” said Schulgen. “I hope the American people don’t forget.”

Here, they don’t.

Laura Pokorney hadn’t seen her stepson in 11 years when she went to meet Marine First Lieutenant Frederick Pokorney Jr. at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in January. The reunion for the San Bruno resident and her stepson lasted five days. Then Frederick Pokorney, 31, left for Kuwait.

He won’t be coming back.

Laura heard on March 24 that Pokorney was killed in Iraq. He was one of nine Marines who died after an encounter with Iraqi troops near An Nasiriyah.

During her January trip, Laura also met Pokorney’s wife, Carolyn Rochelle Pokorney, and their 21/2-year-old daughter, Taylor.

“It was amazing what a wonderful man he’d grown into and an honorable man,” said Laura. “He loved the military … and he was a wonderful husband and a good father.”

She and her children are flying to Virginia today to attend his funeral in Arlington National Cemetery on Monday.

She said the pain of losing her stepson is tough, but she never questions the necessity of the war.

“You get angry and upset and ask why,” she said. “He was so strong into it. I told him every day I was there how proud I was of him.”

Both of her other children are engaged, and they were waiting to be married until Pokorney came home.

Pokorney was born in California. His parents divorced when he was very young, and his father remarried Laura.

Laura said Pokorney’s birth mother dropped him off when he was 5, saying she could no longer care for the boy. She and his father raised Pokorney with Joshua, now 23, and Sylvia, now 25. Joshua remembers playing army with his half-brother as a kid.

“He was like the older brother, he’d take you everywhere he went,” said Joshua.

The family moved from California to Oklahoma in the 1980s. In 1986, the family moved to Tonopah, Nevada.

While in high school in Tonopah, Pokorney flourished. The 6-foot-7 athlete played sports and was at the top of his class academically and socially.

But when the family moved to Redwood City in 1988, Pokorney stayed in Tonopah moving in with Wake and Suze Lieseke, whom he “adopted” as parents.

In 1989, he came to visit his father in Redwood City and they “had words,” Laura said. Pokorney stopped talking with Laura, his father and his siblings.

Pokorney joined the Marines in 1993 and graduated from Oregon State University two years ago.

Laura said Pokorney’s father left her and their two children in 1991.

Two years ago, Pokorney contacted Laura. She said they restarted their relationship.

“He just showed me his life,” said Joshua. “He was a family man, responsible.”

Contributions to the Pokorney family fund can be made to the U.S. Navy Federal Credit Union, bank account number 2742243005.

From a press reports: 29 March 2003

CHELLE POKORNEY, HUSBAND DIED IN COMBAT:

“He was the most an honorable man you could ever, ever know and I please want everybody to know that. Everyone of you. I don’t want it. I want him – he was just such a gentle giant and such an honorable Marine. And he loved his family, he loves me and my child, and he loved his family, and he also loves his Marines.”

Chelle will have constant reminder of her husband right in her own home. She says their two-year-old daughter Tayla Rochelle looks just looks like her father. She says she will remember her husband each time she looks at her daughter. Chelle is planning a funeral with full military honors for her husband at Arlington National Cemetery.

TONOPAH, NEVADA — Fred Pokorney became a star by shooting hoops on the high school basketball court, and Friday the town gathered in that same gym to share stories, shed tears, and offer hugs in memory of Nevada’s first known casualty in the war with Iraq.

“Fred was a hero,” Wade Lieseke, who served as a surrogate father for Pokorney since his high school days, said after the hourlong memorial service. “He died a hero, and he’ll always be a hero to all of us.

“We’ll miss him for the rest of our lives.”

First Lieutenant. Frederick E. Pokorney Jr. was killed Sunday outside An Nasiriyah when Iraqi soldiers appeared to surrender but then opened fire. Eight other Marines, also from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina., died in the attack.

He leaves behind his wife, Chelle, and their 2-year-old daughter, Taylor. He is scheduled to be buried April 14 at Arlington National Cemetery.

“Tonopah High School was an important part of his life,” Principal Barbara Floto told about 350 children, students, veterans and residents lining the bleachers, many carrying small U.S. flags. “He gave and took valuable memories.”

“Those of us who knew Fred will treasure his very being,” she added. “We pay tribute to a young man who will always be a part of us.”

Floto then signaled student body president Beth Gaydon to present the Lieseke family with 31 red roses for each of Pokorney’s 31 years.

Pokorney grew up in the Bay Area with his father, Fred Pokorney, but when he was 16, he moved to Tonopah to live with an aunt. When she died, the young man joined the Lieseke family, although he was never legally adopted.

“I didn’t have to — he was just our boy,” Lieseke said.

He excelled in sports — his 6-foot 7-inch, 220-pound muscular physique landed him top spots on the varsity football and basketball teams.

And he endeared himself to many in this isolated mining-military town of 3,500 people in the eastern Nevada desert.

Many cried during the service and stood with arms around each other afterward.

“It’s a very small community, so it hits us hard,” local resident June Downs said after the ceremony.

“He was a good guy, a caring guy, considerate of others,” added his former classmate J.D. Gray. “I saw him at our high school reunion and he was excited about being in the service. He was doing what he wanted to do.”

The Rev. Kenneth Curtis offered some comfort by reading from Ecclesiastes — a passage entitled “a time for everything.”

“Everything that happens, happens at a time of God’s choosing,” he said. “A time to be born and a time to die. A time to kill and a time to heal…”

It seemed the most fitting thing to say when you’re looking for answers and there are none, he said.

“It’s hell when you have to bury your kids,” he said after the service.

The school’s choir then sang “Tears in Heaven,” a song Eric Clapton wrote when his young son died in an accident.

As Lieseke wept throughout the song, his daughter, Christina Uribe, rested her head on her father’s shoulder.

Her dad stroked her hair.

“Words can’t express what they’ve endured in the last week,” Christina’s husband, Staff Sergeant Joe Uribe, said after the gathering.

Lieseke’s other daughter, Angie Casey of Reno, had a baby just one week ago and was unable to attend the service. Casey dated Pokorney for four years starting in high school. Although they lost touch, his death struck her deeply.

“I just have to be strong because that’s what Fred would want us to be,” she said from her Reno home, her newborn crying in the background.

Lieseke’s wife, Suzy, has stayed with her daughter since the birth to help her with the infant and her three other children.

“It upset me terribly that I couldn’t be down there,” she said in tears. “He was just really a good kid — you couldn’t ask for more. He was a nice boy and who turned into a wonderful man.”

“The few years he was in our lives he blessed us and we provided him with stability when he needed it,” she added.

Pokorney, who went to the Middle East as a Second lieutenant, was promoted posthumously effective the date of his death, the Pentagon told the Associated Press. He had been selected for a promotion, but had not received official word before his death.

Fred Pokorney’s uncle, Gary Pokorney of Custer, North Dakota, said he has been in contact with the Marine’s biological father, who now lives in the Midwest.

He is saddened by his son’s death, the uncle said, referring to the junior Fred Pokorney by a family nickname: Benny.

“He’s OK,” Gary Pokorney said Friday in a telephone interview. “He regrets not being able to see him in recent years.”

“He’s disturbed that he died, but believes he died for a good cause,” the uncle added.

27 March 2003:

‘Gentle giant’ of a Marine mourned

‘I knew he wasn’t coming home,’ says Pokorney’s widow

CAMP LEJEUNE — When Chelle Pokorney saw her husband, Second Lieutenant Frederick E. Pokorney, off to Kuwait, something told her she wouldn’t see him again.

“When he left, I knew he wasn’t coming home,” she said Wednesday at Camp Lejeune. “He didn’t have to tell me. I had a feeling.”

Pokorney, 42, died Sunday in battle near An Nasiriyah with eight other Lejeune Marines. He was a field artillery leader and was likely a forward observer with the 1st Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment.

Chelle, a part-time nurse at Onslow Memorial Hospital, spoke to reporters Wednesday. It was her first public comment since she found out her husband was killed by Iraqi forces during an ambush.

Her voice quaking at times, she called her husband a “gentle giant” and said he loved his family, the Marine Corps and the Oakland Raiders. She said he was an honorable man, who lived up to the Marine Corps’ standards of “honor, courage and commitment.”

She couldn’t explain why she knew she would never see her husband again when his bus pulled away for the first part of the journey to his deployment to the Persian Gulf and war with Iraq.

“I think it was the love that we had,” she said.

But she couldn’t ask him not to go.

“What can I do?” she asked. “He was a Marine. He did what he loved.”

The news has been hard on their 2-year-old daughter, Taylor Rochelle, “his spitting image,” she said.

“She is hurting now,” she said. “My daughter is going to suffer not having a father, but she had him for a very short time.”

Frederick Pokorney is going to get a full military funeral in Arlington National Cemetery, with all the honors befitting a hero, she said.

She said it was important to support the families of Marines deployed in Iraq now. Most of them receive little contact while their husbands are deployed in conflict.

“The wives are brave,” she said. “We need to support them as a nation.”

Chelle last spoke with her husband on March 4. It wasn’t their anniversary, but he knew he wouldn’t be able to call her later, and he wanted her to know how much he loved her, she said.

Their seventh wedding anniversary would have been Saturday.

“That call was a blessing,” she said.

She said it was also important to remember the Marines who are still in Iraq.

“There are many Marines that are still over there,” she said. “My husband led them until it was his time.”

Senator Reid’s Statement On the Death of Marine

Second LieutenantFrederick E. Pokorney, Junior

Thursday, March 27, 2003

“Nevadans have lost one of our own in the war against Iraq. Frederick Pokorney of Tonopah was killed in battle in Iraq on Sunday. Nevadans will always be grateful for his sacrifice. The world is a better place because of his service to his country.

My thoughts and prayers are with Frederick’s wife and family today, and with the people of Tonopah who grieve for their friend and neighbor. I remain committed to helping all our Nevada servicemen and women in any way I can. I hope all Nevadans will join me in that effort.

Frederick Pokorney’s death is a loss for all of us. It’s the first loss that Nevada has suffered in this war. We all hope that it will be the last.”

Marine’s widow says war coverage tries families

JACKSONVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA — March 27, 2003 – The wife of a Marine killed in combat in Iraq says the intense media coverage and instant images of battle carnage are making the war especially tough on the families of military personnel.

Shelley Pokorney of Jacksonville said the massive coverage of the war brings raw information to families worried about their loved ones. “It makes it worse,” she said. “It’s horrible for the families.”

Pokorney, who faced a horde of reporters in a news conference at the Camp Lejeune Marine Corps base, said she had a message to broadcast about the loss of her husband, Second Lieutenant. Frederick Pokorney Jr.: “He’s our hero, and he’s a hero for our nation. I’m so proud, and I just want to let you guys know that,” she said.

Her husband, an artillery officer, was one of nine Marines from Camp Lejeune killed over the weekend in Nasiriyah when Iraqi soldiers faked a surrender and fired on Marines. The attack was widely reported well before official word of casualties came from the Department of Defense.

Marine Corps officials at Camp Lejeune confirmed the toll late Monday as chaplains began notifying families in Jacksonville and elsewhere.

Besieged with calls from local and national media outlets, Pokorney and her family scheduled a news conference at her home in a Jacksonville suburb but moved it to Camp Lejeune to accommodate the large turnout. They faced television cameras, photographers and radio and newspaper reporters.

Pokorney, who said she wants her husband to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, said he was a Marine doing what he wanted to do for his country.

“There’s good and evil in this world. That’s what’s going on,” she said. “And he was the good.”

Press Report: 26 March 2003:

TONOPAH — If the U.S. Marines were looking for a Marine to show off to the rest of the world, Scond Lieuteant Fred Pokorney could have been that man, said people in this small central Nevada town where he went to high school and still has many friends.

“That’s the best thing you could say about Fred,” said Wade Lieseke, who served as sheriff of Nye County for 12 years and was the man Pokorney considered his father. “He had character. He had morals. He had integrity. He was the epitome of what a Marine should be.”

Pokorney, 31, was killed in battle Sunday when a group of Iraqis feigned surrender and instead shot a group of Marines dead. He was Nevada’s first casualty in the war against Iraq.

“Anyone that was blessed by knowing Fred has suffered an indescribable loss. We all hurt deeply,” the family said in a statement issued in Jacksonville, North Carolina, where his wife, Carolyn Rochelle, and 2-year-old daughter, Taylor, live.

Officially, the Marine Corps will say only that they are still investigating the Sunday encounter that left Pokorney and at least eight other Marines dead in the vicinity of An Nasiriyah, Iraq.

“We just don’t have the information to say what happened,” Navy Lieutenant Commander Charles Owens said in a telephone interview Tuesday from the Marines’ forward command at Camp As Sayliyah, near Doha, Qatar.

But after the battle Sunday it was widely reported that the Marines at An Nasiriyah were killed when an Iraqi unit holding a white flag opened fire as U.S. forces approached.

Pokorney’s family is making arrangements to bury him in Arlington National Cemetery.

“I don’t know what his family’s going to do,” Lieseke said. “He was just their rock.”

Pokorney’s wife, known as Chelle, was not talking to reporters Tuesday. Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev., spoke to her.

“You can tell that she was very proud of him and that he was going to Iraq to make the world safer,” Berkley said. “He was a good husband and good father. She obviously had deep love and affection for him.”

Lieseke said Pokorney met Chelle while he was stationed in Washington state a few years ago. They married about four years ago, he said.

Pokorney enlisted in the Marine Corps in February 1993 and was promoted in March 2001 to a command field artillery officer, according to Marine Corps spokesman Michael Giannetti. He was assigned to the Headquarters Battery, 1st Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade. The unit left in January from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Lieseke, 52, said he met Pokorney about 15 years ago, when the teenager was dating Lieseke’s daughter. Pokorney was living with an aunt in Tonopah because, Lieseke said, his mother had died and he did not want to live with his biological father in California.

But Pokorney’s aunt died when he was about 17 years old, Lieseke said, and Lieseke and his wife, Suzy, took him in.

“He stayed here with us,” Lieseke said during an interview Tuesday in his home. “We raised him like our own. He listed us as his mother and father on all his military records.”

Pokorney was remembered around Tonopah on Tuesday as a star athlete, a solid student and a dedicated Marine and family man.

“We’re going to miss a good person, that’s for sure,” said George Robertson, who owns a Chevron station in town. He said his son went to high school with Pokorney.

At Tonopah High School, Principal Barbara Floto said Pokorney’s death hit some of the students hard.

“Once they realized the impact of the loss of an alumni, they changed from, `Oh, this war doesn’t necessarily affect us here,’ to, `Wow, this really hits home,’ ” she said.

Students in the school’s leadership class made banners reading “God Bless America” and “We support our troops” that were hung in the hallways on Tuesday.

Floto said the students were proud of one they painted in Marinelike camouflage colors that paid tribute to American troops.

Pokorney was particularly adept at sports. He stood 6 feet, 7 inches tall, Lieseke said, and played both football and basketball.

He played wide receiver, tight end and outside linebacker on the Muckers football team. He was the basketball team’s center, recalled Jim Smyth, a Las Vegas attorney, who was his teammate and classmate and “rode long bus rides” with him. “I’m horribly saddened by his death. … He was a quiet kind of guy. All he was about was playing sports and hanging out with his girlfriend.

“Unlike the rest of (the) kids from the desert, he kept his nose clean. He didn’t go out and drink beer. He was quiet and reserved and did his thing,” Smyth said.

Fighting back tears, Janet Dwyer, secretary at the high school, recalled his return to Tonopah after boot camp. “I remember him coming back and being all excited in uniform. He was just so proud to be a Marine.”

In Washington, Rep. Jim Gibbons, R-Nev., who flew combat missions in the first war against Iraq, called Pokorney a “hero among heroes.”

Floto, the school principal, said Gibbons called the school on Tuesday to offer whatever help he could.

She said a memorial service is planned for Pokorney at 8 a.m. Friday at the school.

Lieseke, who served as a helicopter gunner in the Army during the Vietnam War and received two Purple Hearts, said Pokorney excelled as a Marine because he had always sought order and stability in his life.

“Fred’s mood was always serious,” said Lieseke, who spent 22 years with the Sheriff’s Department before losing a bid for a fourth term as sheriff last year. “He liked the discipline. He liked the order.”

He received his most recent promotion after graduating from Oregon State University with a degree in military science, Lieseke said.

“The Marine Corps decided he was officer material and sent him through college,” said Lieseke. But he added, “A lot of good it does him now.”

As proud of Pokorney as Lieseke is, he said he is also bitter that the young man had to go to Iraq at all. “There’s not a million Iraqis worth Fred’s life,” he said.

He said he is hazy about the circumstances of Pokorney’s death, and suspected he will always remain so.

“I’m just not sure it’s for us to be the liberators of Iraq. Why does it always have to be us?” he asked.

Tuesday, March 25, 2003:

North Carolina Town Grieves After Marines’ Deaths

JACKSONVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA — It was supposed to be a joyful week for Corporal Jarred Pokora, with a brief leave to celebrate the birth of his daughter before a possible deployment to Iraq. But news that at least 11 Marines from Camp Lejeune have been killed in Iraq has plunged this garrison town into mourning.

“You live, you work, you do everything with these guys,” said Pokora, a 21-year-old member of the 2nd Marine Expeditionary Force from Springfield, Illinois.

He serves in the same regiment as Second Lieutenant Frederick Pokorney Jr., one of the nine Marines killed Sunday in fighting near An Nasiriyah, 230 miles southeast of Baghdad.

Pokorney’s brother-in-law, Rick Schulgen, said the family was grieving for “a proud father, a proud husband and a proud Marine” that they hope to bury in Arlington National Cemetery.

“His first love was his family. His second love was the Marines,” Schulgen said. “Anyone that was blessed by knowing Fred has suffered an indescribable loss. We all hurt deeply.”

Also among those killed was Lance Corporal David Fribley, 26, of Fort Myers, Florida. His father said Fribley knew Americans could face tactics like those used by the Iraqis near An Nasiriyah.

“That’s part of war,” Garry Fribley said from the family’s home in Atwood, Indiana “It’s time to take the gloves off. We’re so intent on being the nice guys, and they (Iraqi soldiers) are not going to abide by anything.”

Two other Camp Lejeune Marines have died in non-combat accidents.

The U.S. flag near the USO center flew at half staff and an enormous yellow bow was tied to a railing outside. Some 17,500 of the 30,000 Marines assigned to Camp Lejeune are overseas, and flags and signs in their support dot roadsides and businesses all over Jacksonville.

Matt Sutton, 35, a Marine corporal in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, said the deaths have hurt the Camp Lejeune community.

“I feel for the Marines and for their families,” said Sutton, now a service manager at a tire company. “I anticipated casualties. It’s not a piece of cake like it was last time.”

Pokorney, 31, lived in a cream-colored house outside Camp Lejeune. A white mailbox at the end of the driveway was adorned with a pink bow, interlaced with a red, white and blue ribbon.

Pokora knew Pokorney’s name, but didn’t know him; the two were in different battalions. He said he was torn between grief for his lost comrades, joy at the arrival of his baby and his own preparations for war.

“The training is a lot more serious that we’re doing now,” he said. “There’s a bigger reason to train harder.”

Among the Camp Lejeune Marines still overseas is Private David Stone, 32 – on his first combat operation, his wife said. Sharea Stone said her husband is assigned to field artillery in Iraq.

“When my husband left (in January), I just thought of him being overseas. I never looked at it as I look at it now,” said Stone, 29. His absence now is “stressful, very stressful. I think about him, whether he is OK.”

In a Jacksonville trailer park, children’s toys dotted the yard outside the mobile home Sgt. Michael E. Bitz shared with his wife, Janina, and their four children.

The family included infant twins Bitz never saw. He left for Iraq in January, the babies were born in February and he died in combat on Sunday.

Bitz’s mother, Donna Bellman, said her son drifted from job to job after graduating from high school in Ventura, Calif. She urged him to join the Marines, and she never worried until the war began.

“I had this terrible feeling since he shipped out in January. … I kept trying to picture a white bubble around him to keep him safe,” she told the Ventura County (Calif.) Star. “But it didn’t work.”

Also among Sunday’s victims was Corporal Jose A. Garibay, 21, of Orange County, California. Janis Toman, a resource specialist at Newport Harbor (California) High School, received a letter from him Monday and was putting together a package of cookies and candy when she learned he was dead.

“It felt like a punch in the stomach,” she said. “He’s one of the kids I feel I made a difference in his life. He’s one of the reasons you want to teach.”

March 27, 2003:

An Oklahoma couple is mourning the loss of their grandson, a U.S. Marine killed in combat.

Marine Second Lieutenant Frederick E. Pokorney Jr., 31, of Tonopah, Nevada, was killed Sunday during an ambush in An-Narisriyah, Iraq.

One set of Pokorney’s grandparents lives in Pauls Valley. Pokorney also trained at Fort Sill in Lawton last summer.

Chelle Pokorney, the soldier’s widow, called her husband a hero.

“We’ve lost a wonderful person. We’ve lost a wonderful Marine. And this nation is going to grieve. And I want us to grieve. And I want us to go on and I want to make this the most positive thing that has ever happened to me because it has been the most horrible experience. But I hope to go forth and carry my husband. He was a hero. He died a hero,” she said.

Pokorney is survived by his wife and a young daughter.

March 2006:

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers,

And that cannot stop their tears.”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning,

The Cry of the Children

Outside of their travel trailer, a television crew was setting up a camera and lights. Chelle and Taylor Pokorney had been living in a place called Trailer Park Village in Quantico, Virginia.

Seven months after her husband, First Lieutenant Fred Pokorney, Jr., had been killed in Iraq, Chelle was still emotionally raw, and uncertain of what to do next. She told the visitor sitting at her table that leaving the Washington, D.C. area was like leaving her husband, who had been buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Too many issues were still unresolved for Chelle Pokorney to move to whatever it was that came next for her and three year old Taylor.

“I’m waiting for the report from the Marines on the investigation of the A-10,” she said. “The whole friendly fire thing. People say, ‘is it gonna help if you know every detail?’ Well, yeah, that was my husband. I wanna know every detail up to the time it happened, and what he said, and who he was with because that’s what you hold onto. I never got to say goodbye.”

Chelle’s husband, who saved the life of Lieutenant Ben Reid, and called in critical air strikes while under attack, was originally recommended for a Bronze Star. However, officers later upgraded commendation to the Silver Star. Waiting for word on his medal has left Chelle Pokorney feeling more pain was inevitable. After Lt. Pokorney died in Al Nasiriyah, all of his mail came home to Chelle in one shipment. It arrived on the same day as his memorial service. None of the letters she had written or photos of Taylor had ever found their way to her husband. A simple thing like the absence of a house keys from his personal belongings can leave her aching.

“I keep waiting for closure, you know, keep waiting for closure,” she repeated. “I never got the house keys back. Nobody can understand that. It’s just that it doesn’t mean anything to them, but that was your husband who didn’t come home, and that was the key to open the door. And it was home. Nobody can understand that pain. They just think you’re silly because you hold on, and you’re crazy.”

On the settee in the trailer, Chelle had placed a framed photo of her husband, who is wearing camouflage, and casting his resolute eyes in the direction of the camera. It is the first thing the visitor sees when stepping up into the living space. Taylor Pokorney looked at the photo many times a day.

“See,” she said. “There’s my daddy. He’s looking right at me from heaven.”

Chelle rubbed her daughter’s back. None of the adults in the room spoke. Chelle and Taylor had just returned from a trip to New York City. By telling her story of the financial confusion and the challenges of grief, Chelle believed she had the ability to help other families deal with the complications of their loss. As a guest of the Fallen Heroes Foundation, Chelle had hoped to use her time during an appearance on The Today Show to talk about what military families were facing with combat fatalities. Instead, interviewer Matt Lauer spent most of the air time quizzing Gen. Tommy Franks, who sat next to Chelle, about the U.S. military’s tactics in Iraq.

By now, it ought to have been getting easier, she figured. But it wasn’t.

“Right now,” she explained in 2003, “I want to tell my story because there’s huge financial changes. There’s a lot of need. I find out every day there’s something new. It’s been seven months and I still don’t have the answers to what we get and what we don’t get. Taylor still doesn’t have dental insurance. Wow, daddy gave his life, and I still have to fight with them [the military] to get it. [health insurance] Why, I ask? There is supposed to be somebody to help me but they don’t get what help is, so they don’t make it happen. I wanna help those other families so they don’t have to go through what I’ve had to go through for seven months.”

Chelle walked over to the counter and ran water to pour into the coffee machine. She had trouble talking without crying. She said that after Fred died, the first casualty assistance officer the Marines sent to her home was drunk. After telling her she ought to be stronger because she was a Marine’s wife, and more grateful because her husband got to be buried in Arlington, Chelle said she ordered the officer out of her home. There were two others assigned to her and Taylor. Insensitivity was something Chelle Pokorney never expected from the Marines or the American public.

“I was real positive from the beginning that this is what Fred did, this is what he gave his life for; he was a Marine, and that is the reality, and people say that, and that’s probably the worst thing you could say to a military family; that you knew what you signed up for because nobody wants this to happen, and that’s such a terrible thing to say. Including one of the media guys I was on with who said, “You knew the reality of this. What were you thinking?’ How heartless. How heartless. How heartless can you be? But you never want a little girl to lose her daddy. It’s the reality, yes. But god, when it happens don’t stop and tell a family you signed up for this, you knew what you were getting into, because it’s horrible.”

“We’re all set.”

The television producer leaned his head into the open door of Chelle and Taylor’s trailer. A camera sat on a tripod next to a picnic table. Chelle stepped out into the October light, running a single finger across the wetness beneath each of her eyes. The Virginia air was cool, and stirring, lifting the leaves cluttered along the edge of the blacktop. Taylor followed after her mother, stopping to check on her German shepherd, waiting inside his cage for a walk. Her face is the face of her father, rendered in the feminine. The cheeks are full, and her eyes have already become serious with independence.

“How’s she doing?” Chelle was asked.

“Oh, she’s doin’. She’s coming back. She’s got his light, and his stamina, and she misses him.”

“And she knows what happened?”

“We were talking about it last night. She said, ‘Why did those bad people kill my daddy?”

Taylor caught up with her mother and pulled at her sleeve. “I wanna go find some nuts,” she said.

“Well, go find some for me, buddy,” Chelle said. “So we can feed the squirrels.”

Taylor ran to the edge of the pavement and began digging among the fallen leaves, searching for acorns. Her mother, too tired to constantly hold off the tears, was talking about an encounter with another military family.

“We saw another little boy,” Chelle Pokorney said, “And she said, ‘Why did his daddy have to go too?’ And she said, ‘Is his daddy in his heart like my daddy is in mine?’ She knows. We miss him. We have to talk about him to keep him alive because he’ll never be able to hold us again, and I wish…..”

She turned her head, looking away, looking for something.

“He was a wonderful father,” Chelle said, finally. “Just wonderful. And a wonderful husband.”

Staying near the Marine base at Quantico, Virigina had been both agonizing and healing for Chelle Pokorney. There are great memories lingering there; her husband in his dress blues leaning down to embrace her for a dance, a first camping trip for Taylor, cookouts and conversations with friends who had chosen a life of military service. If Fred were to be posthumously awarded the Silver Star, Chelle hoped that it might be presented to Taylor on the base at Quantico. But she was on the move now, no longer confident that everyone in the military was possessed of honor and responsibility like her husband. Chelle had already sold their modest house in the neighborhood outside Camp Lejuene in Jacksonville, North Carolina, because she felt no longer a part of the Marine family.

“I thought I could stay in the military town I was in,” she explained. “And I’d have some more support, and people would never forget, and I thought, wow, this is my family. But a few months later, after everybody came home, the reality is that Taylor and I were alone. A few people trickled by. But they mostly weren’t there, and the days that they weren’t there were so empty. People come up to me and say, ‘We thought you moved,’ and I just sit there and say, wow, you never called. You never came over, so how can you say that? Those are just such empty promises and words. How can you say that? You don’t know how that affects us. So we left.”

Chelle sat down with the interviewer. Another camera was pointed at her face. This was not the role she wanted to play. All she wanted was her husband, her daughter, and a quiet family life of holidays, vacations, and the contentment of knowing her husband was fulfilled by his service to his country. Instead, she has been consumed with a sense of obligation to speak the truth, honorably, as her husband would, about her loss, and what all the families of those lost in combat are confronting. In a way that she was unable to ignore, Chelle Pokorney had become a symbol. She reminded families, who had soldiers or Marines still in Iraq, that their loved one might not come home, either. No one wanted that reminder. People stayed away from the Pokorney house.

“When you lose your Marine, and you lose your husband, and your best friend, and your daddy,” Chelle said, “You hold onto what people say to you, and when they let you down, it’s the most horrifying thing. It’s worse than just reliving his death over and over again.”

Chelle Pokorney’s support for the president and the war in Iraq had not yet wavered. She loved the president, and trusted his judgment, just as her husband had. In her opinion, George W. Bush has the most difficult job in the world, and he would not put American troops in danger unless he felt it were necessary to protect the country. The angry polarization of Americans, sharply divided over the war, had not affected Chelle’s beliefs in the months after he husband became one of the war’s first casualties. Although she admitted to not being political, she was worrying for the soldiers and their families when she heard people criticizing the American presence in Iraq. She told herself that debate was precisely what Fred died for, so that people can have free and open discussions, say and do what they want, whether they are in the U.S. or Iraq. That’s what she knows. That her country is beautiful, still, no matter what the political climate might be. And her husband loved it, and would die for America a second time, if only he were given a chance.

“I’m going to visit him every Memorial Day.” Chelle was sobbing, the unabashed tears of a deep, deep sorrow, an agony she was uncertain would ever let her be. “It’s the least I can do for his little girl; take her to Arlington to see him. Because he was so proud on Memorial Day when he was with those veterans. He was just so proud to be a part of that, and that tradition, and thank them for what they did. And he did. Fred never forgot. He never forgot.”

Taylor Pokorney reached up and took the hand of her new friend and led him in the direction of the playground while her mother was being interviewed. After filling her knit cap with acorns, she had lost interest in looking for more. She clambered over the plastic playscape, constantly talking about the make-believe situations she was creating. Although the sky was clear, she told her friend the rain was going to begin falling and he needed to climb up the slide for protection. When she jumped on a spring-mounted rocking horse, Taylor asked to be pushed. As the toy animal swung slowly back and forth, she grew quiet, and quit leaning her slight weight into the pitch and roll of the little horse.

“Stop. Stop,” she said.

Instead of getting down, Taylor kept her grip on the red handles near the horse’s neck. She looked up to the unfamiliar face.

“All my friends are sad,” she said.

He did not know what to say. Her short, brown hair began swaying again as Taylor worked the horse back into motion. She had not expected a response. It was just something that had registered with a child, and she had given voice to what she knew. By the time they returned to the trailer, the television taping was concluding. Taylor urged her mother to let her dog out of the cage.

“Can we take him for a walk?” Taylor pleaded.

“Sure.”

Chelle opened the gate, and clipped the leash to the dog’s collar. Taylor had named her pet “Stich,” after the movie Lilo and Stich, which had been her favorite movie she had seen with her daddy. The dog pulled hard at his restraints and Chelle hesitated to hand the leash to her daughter.

“By myself. By myself,” Taylor insisted. “Sit Stich. Sit. Come here. Let’s take a walk.”

While the dog began pulling the little girl, the camera crew followed, and Chelle tried to articulate where she was in terms of healing. She understood grief. She was a nurse. All of the signs were there. It was a process. But it seemed like it was taking too long. She needed to go on. New York had opened doors. She had been offered a position as the honorary co-chair of the Intrepid Foundation. The job meant resources to help other military families deal with their casualties, the absurd bureaucracies, uncertain benefits, loss of health care, and the complications of moving on to another life. But she wanted to go home to Washington first. Be with her parents and her brother. Process things some more. Feel the broken places inside of her start to mend before she went back into the world.

“A part of me thinks people just want to avoid me,” she said. “It’s too real for them. And hey, who wants to be around somebody who cries all the time? Or somebody who reminds them of what could happen to them? I’m thinking that’s okay for me. I can deal with that. But what about Taylor?”

It is difficult for Chelle Pokorney to think that her husband gave his life in service to his country and his daughter’s future has become more uncertain. When a Marine dies in combat, he stops getting paid the next day. The death benefit he signed up for is usually enough money to help his survivors make a transition to a future without him. But it is not always sufficient. Chelle expected to return to work as an RN, but was unsure about earning enough to comfortably get Taylor from age 3 to 18. College, without her father’s income and commitment, seemed an improbability. Why didn’t the government have any mechanisms to help military families deal with these issues? Who takes care of the families of servicemen and women who have died in combat? Are they really just tossed aside?

Taylor, frustrated with her mother’s distractions, and the intrusive television gear, interrupted the conversation to talk about Stitch.

“He doesn’t like the camera,” she explained. “He likes walking. Let’s walk him. Come on, mom. Stich, heel. Heel, Stich.”

When her husband was alive, Chelle Pokorney worried about very little. Sure, there were the usual financial challenges of any military family. But she was confident they could handle those. Fred’s presence, their love, gave her confidence everything was fine, and getting better. He always assured her that if anything ever happened to him, the Marines cared for their own, and their families. She would be okay. The military was her family. That’s the code of conduct Fred Pokorney would have lived up to if one of his own men had been killed in battle, and Fred had come home. But that’s not what happened for Fred’s wife.

“That’s the first thing my mom said to me when this happened,” Chelle said. “She said, ‘You are going to be alone because Fred’s gone, and no one is going to be there for you.’ She was right because I thought, at first, when everybody was there, and it was all hot and heavy, and they said, we’re your family, we’re gonna take care of you. And it wasn’t true.”

After Stitch was put back into his cage, Chelle showed the television crew an album of photos. Her life with Fred and Taylor was shining across the pages. As each page was turned for the camera, Taylor pointed.

“Oh look, I’m eating cake. Oh, daddy loves me. Oh, I’ve got a bottle ’cause I’m a baby. See, my Daddy’s got something in his hand.”

Chelle’s eyes were wet again. She was doing this to keep alive her husband’s memory, assure that he was not forgotten. He always seemed to do what was right. Fred Pokorney served when called. He made no judgment about why he was sent to Iraq. If there were deceptions or dishonorable men involved in that decision, there was nothing a Marine lieutenant might have done to change things. His only option was to do his job. And he did. Those were the principles in which he believed; fought and died for, and his wife hopes they are what will guide Fred Pokorney’s daughter.

“She said the other night, ‘Mommy, I don’t know if I wanna be a first lady or first president.’ Whatever. You choose. I’ll be stressed. But I can’t stop you. It’s just like your daddy, doing what he loved.”

A few days later, Chelle Pokorney cranked the handle on the travel trailer and lowered it onto the ball hitch of her Ford truck. Her brother, who had also been “emotionally devastated” by Fred’s death, was joining Chelle and Taylor on a cross country run back to Washington State. They planned to stop in Texas to visit relatives, and take Taylor to the Grand Canyon. In Nevada, they expected to see Wade and Suzy Lieseke, her in laws and Fred’s adoptive parents, before turning north, toward home, and Washington.

There was something out there in America for Chelle and Taylor. Chelle didn’t know what it was. There had to be people who cared, and would help, maybe a new job, a different future than the one she had dreamed with Fred. Whatever it was, Chelle was determined to find it. She would just keep going until she did. And for Taylor’s sake she would never, ever give up.

Fred would not forgive her for that.

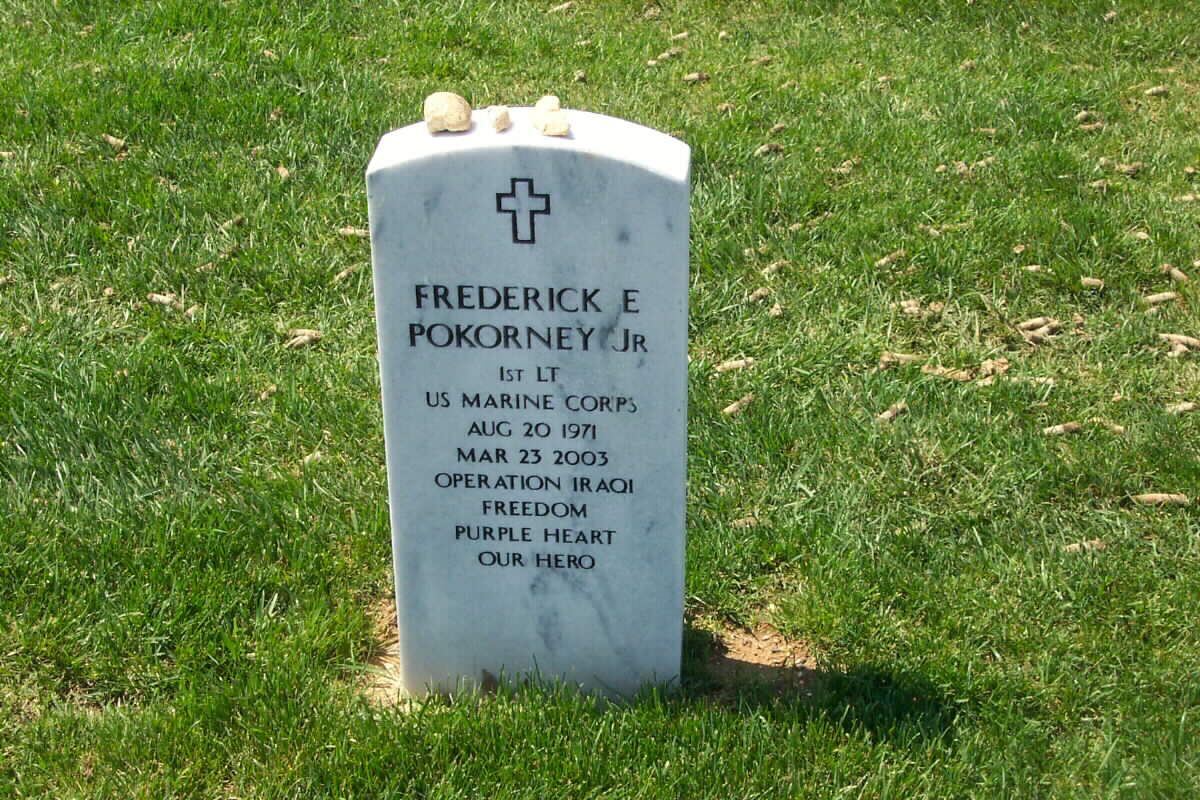

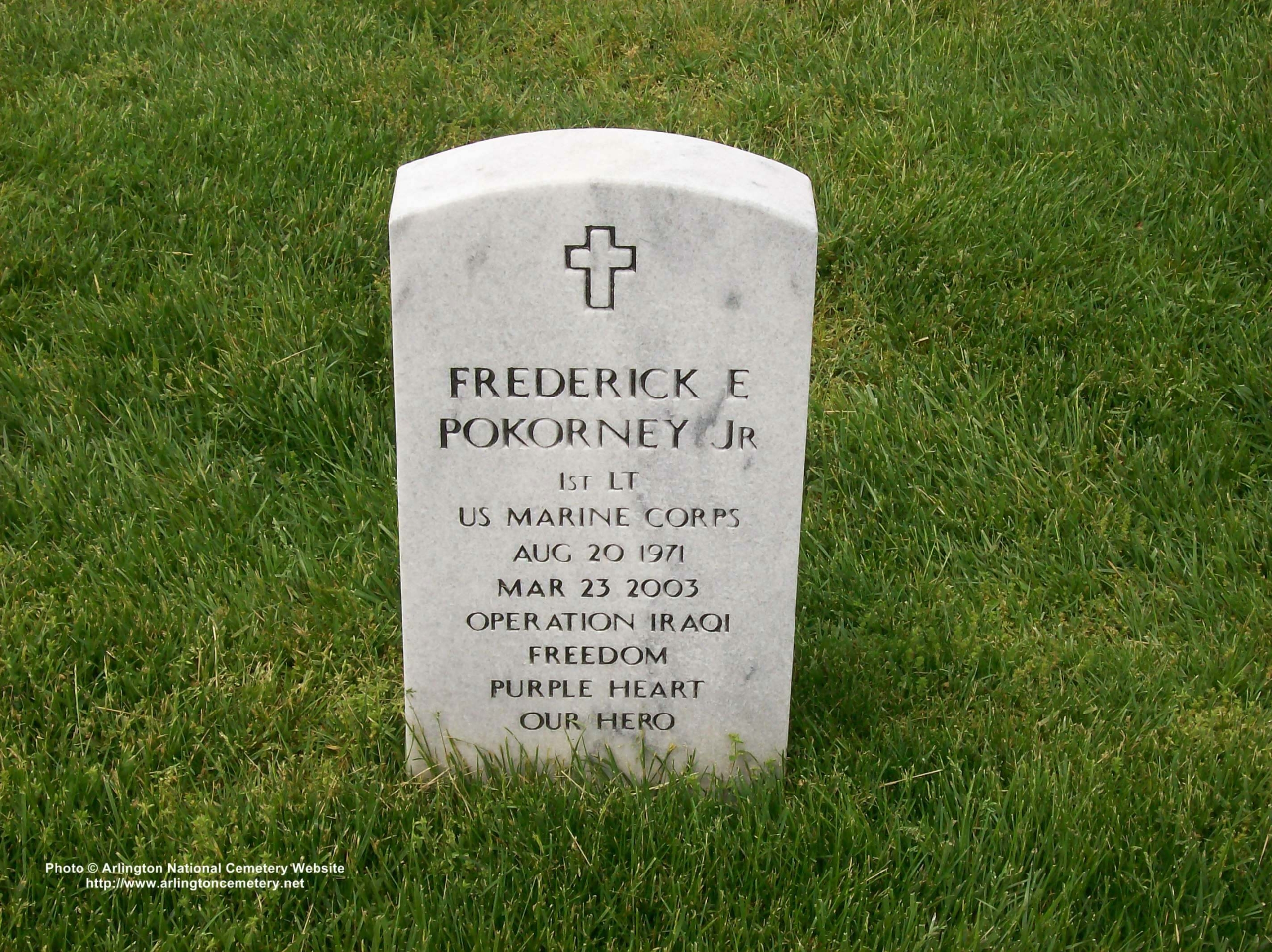

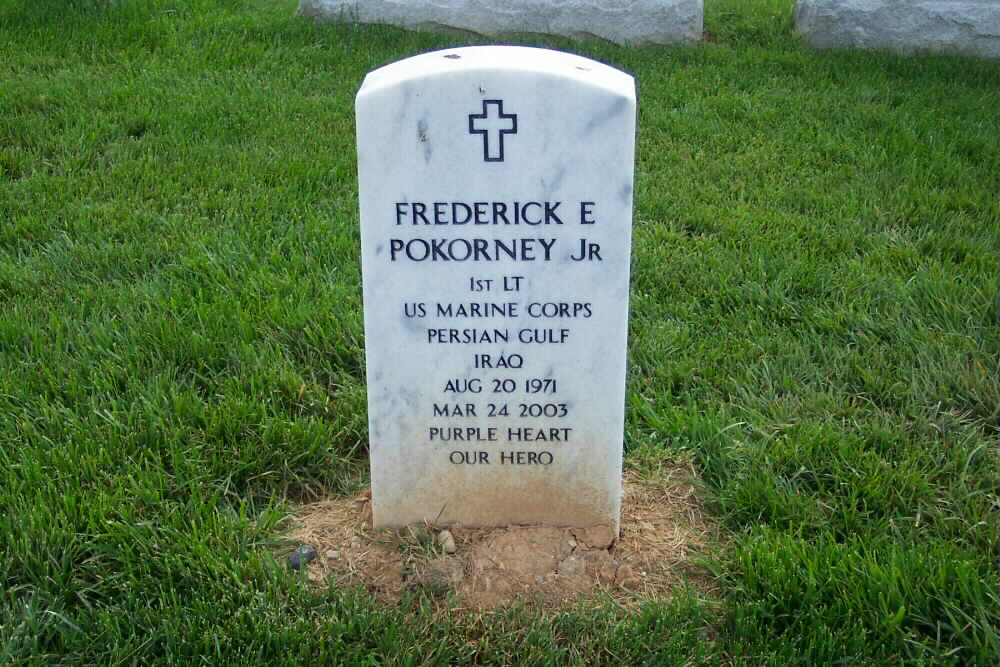

POKORNEY, FREDERICK E JR

- 1ST LT US MARINE CORPS

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 12/16/1992 – 03/24/2003

- DATE OF BIRTH: 08/20/1971

- DATE OF DEATH: 03/23/2003

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 04/14/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7861

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard