By Michael E. Ruane

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Sunday, October 14, 2007

The two old sailors stepped side by side toward the Tomb of the Unknowns, carrying a memorial wreath to their shipmates between them. The crowd stood hushed in the autumn sun while the pair, in ball caps and blazers, approached the white marble monument, left their wreath, stepped back and saluted.

A bugler had just played taps, and as the breeze rustled a majestic elm nearby, the moment was almost perfect: Few seemed focused on the jagged crack that zigzagged through the 48-ton stone like a scar, or the dings and chips in its surface.

But away from the scene in Arlington National Cemetery last week, debate raged over the fate of the nation’s legendary icon to its unknown war dead. The cemetery has long wanted the tomb’s weathered aboveground monument replaced. Preservationists want it repaired and retained. And now Congress is involved.

Two senators, James Webb (D-Virginia) and Daniel K. Akaka (D-Hawaii), added an amendment to the Senate version of this year’s defense authorization bill that would halt any decision on replacing the tomb, pending a report to Congress. And in a letter last month, they urged the same to the Army, which operates the cemetery.

At the tomb Thursday, memories brought tears to the eyes of Harold R. Hayes, 81, of Largo, Florida, who, with Eugene F. Phillips, 77, of Vernon, Connecticut, laid the wreath in honor of their ship, the destroyer USS Gherardi.

“Repair it,” Hayes said of the tomb monument. “Too many people walk through here, see this. . . . Don’t replace it. Repair it.”

Its historic value, Phillips said, is irreplaceable.

The debate goes back years and pits two potent sensibilities: interest in historic preservation and the desire for perfection at the most famous memorial in the nation’s most famous cemetery.

Argument has gone back and forth, mostly out of the public eye, although it is picking up and is “very much alive,” said Richard Moe, president of the Washington-based National Trust for Historic Preservation. “As a matter of fact, it is currently quite hot.”

“There’s a fair amount of interest in this, much of which we are trying to generate,” he said. “We do not think it should be replaced.”

But the cemetery does.

Its mission “is to maintain the . . . monument’s condition and appearance in a manner that fully reflects the honor, dignity and reverence for those . . . it represents,” the cemetery says in a report posted on its Web site. “Repeated repair to a deeply flawed monument will not achieve this goal.”

The tomb — whose sarcophagus-shaped monument is a solid block of marble — dates to 1921. That year, on November 11, the body of an unknown U.S. soldier from World War I was laid to rest atop two inches of French soil inside the tomb’s massive underground vault.

Five years later, Congress authorized a monument to sit atop the vault, and in 1928, the current design, by architect Lorimer Rich and sculptor Thomas Hudson Jones, was selected. Rich, a World War I veteran, is buried in the cemetery within sight of the tomb.

The stone was cut from a quarry in Marble, Colorado, set in place in 1931 and opened to the public the following year.

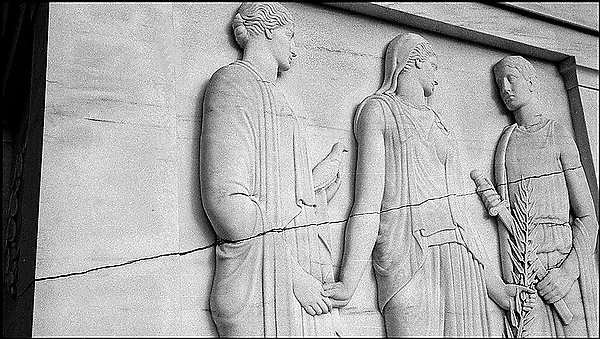

Located on a hillside overlooking the Potomac River and guarded 24 hours a day, the tomb monument bears simple carvings of wreaths on the sides, figures representing Victory, Valor and Peace at one end, and on the other the legend: “Here Rests in Honored Glory an American Soldier Known but to God.”

Subsequently, unknown servicemen from World War II and the Korean and Vietnam wars were interred near the base of the monument, although in 1998 the Vietnam unknown was exhumed and identified. That crypt remains vacant.

According to the cemetery, there has never been a dedication ceremony for the tomb. And although it is called the Tomb of the Unknowns as well as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, it has never been given an official name.

It is thronged daily by tourists who come to pay homage and watch the ritual changing of the guard.

The cemetery report says that minor damage to the monument dates to the 1930s, and the first account of cracks dates to 1963, although they probably existed well before that.

There are two parallel horizontal cracks, both of which have grown in width and length over the years, despite patching in 1975 and 1989, the cemetery says. One crack is 28.4 feet long; the other is 16.2 feet long. Neither is superficial, the cemetery report says, “but extend partially through the block and will eventually extend completely through the block.”

“I’m concerned that [they] will have an effect on the integrity of the tomb itself, as well as its decorative finishes,” cemetery superintendent John C. Metzler Jr. has said.

Rex E. Loesby, a mining engineer and former operator of the quarry where the original stone was obtained, said he believed water has seeped into the cracks.

“Every time it freezes, that water expands,” potentially widening the crack, he said. “It’s just a matter of time before they’re going to see some displacement of the upper part of the stone.”

“They want it perfect,” she said of the cemetery. “I don’t discount that thought process at all. But the only way to put a piece of stone there and make sure it stays perfect is to put it in a controlled environment. That’s why you put things in a museum.”

Sheldon Smith, a spokesman for the Army, said no final decision has been made on the monument’s fate. Many factors must be weighed, he said, including where the cemetery might acquire a replacement stone.

Four years ago, after the desire to replace the monument became public, a retired Colorado car dealer, John Haines, offered to pay for a new stone to be cut from Loesby’s quarry. Haines eventually shelled out $31,000. The stone was cut and ever since has been sitting on a flatbed tractor-trailer at the quarry awaiting conclusion of the debate.

Haines said it’s been frustrating. He owns a huge block of marble that he just wants to give to the government. “They don’t even have to be gracious,” he said. “They just have to accept it.”

But the block might sit awhile longer.

Public sentiment at the tomb last week seemed strongly against replacement.

“To me this is what our country’s about,” said John Zachara of Chicago. “The Liberty Bell cracked. They didn’t throw it away, did they?”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard