D.C.’s ‘Boojum’ Gets His Day in Hall of Fame

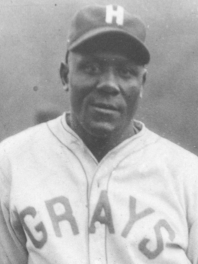

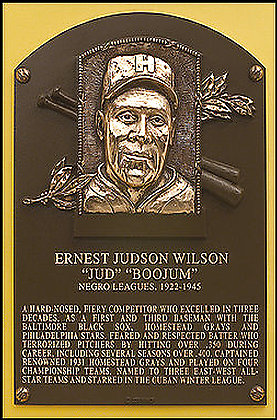

COOPERSTOWN, New York, July 30 — His name was Ernest Judson Wilson, but everyone called him Jud — until the day Satchel Paige heard a line drive produced by Wilson’s bat whiz by his head and started calling Wilson by the onomatopoetic word “Boojum.” And so it was that on Sunday afternoon, when Wilson’s newly minted plaque at the Baseball Hall of Fame was read out loud by his grand-niece, that she took extra care to enunciate the nickname, saying it the way Paige used to:

“Ernest Judson Wilson,” read Sha’Ron Taylor, who accepted her great uncle’s posthumous honor onstage. “Jud Buh-ZHOOM!”

Wilson, a former star third baseman for the Homestead Grays and a longtime D.C. resident who died in 1963, was one of 17 former Negro leagues players and executives who were inducted into the Hall of Fame during the annual induction ceremony Sunday in a grassy field just outside the village.

The day was shared by Bruce Sutter, the relief pitcher of the Chicago Cubs, St. Louis Cardinals and Atlanta Braves, who was elected through balloting by the Baseball Writers Association of America, and whose primary legacy to the game was the split-fingered fastball, which he mastered and became the first to use effectively in the major leagues.

“I would not be standing here today,” Sutter acknowledged during his induction speech, “if not for that pitch.” Noting that his name would forevermore be followed by the words “Hall of Famer,” Sutter said, “It still doesn’t sound right, but it’s sounding better.”

The 17 former Negro leaguers were chosen via a special selection process this spring after a study by a dozen historians, and their induction brings the total number of Hall of Fame inductees to 278.

The Grays, the famed Negro League team that grew to prominence in the 1930s and ’40s while splitting its home games between Washington’s Griffith Stadium and Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, were represented not only by Jud Wilson, but also by ace pitcher Ray Brown and team manager and owner Cumberland Posey Jr. Since all the Negro leagues inductees are deceased, their plaques were accepted and read aloud by a descendant, if one could be located.

Sha’Ron Taylor, Wilson’s great-niece and a resident of Capitol Heights, read about Wilson’s election to the Hall of Fame in a magazine. She remembered Wilson as the ballplaying brother of her grandmother, Wilson’s sister. Taylor was 2 when Wilson died.

“My grandma told me how he used to take me out to Griffith Stadium,” Taylor said in an interview before the ceremony. “He used to take me on the field, after the games.”

Curious about the honor that apparently had been bestowed upon her great-uncle, Taylor called the Hall of Fame and was put through to the person in charge of tracking down relatives of the Negro leagues honorees.

“They didn’t think [Wilson] had any living relatives,” Taylor said, “so they said they were glad to hear from me.”

That is how Taylor came to find herself onstage on a sun-splashed Sunday afternoon, under the television lights, surrounded by some of the greatest living ballplayers of all time — an arm’s length away from Joe Morgan and Eddie Murray and Johnny Bench, among others.

“And my personal favorite, my crush, Ozzie Smith,” Taylor said. “That’s a feather in my hat, being in his presence.”

Taylor and the other relatives of the Negro leaguers were not given the opportunity to make speeches, but if she could have, she would have told them what kind of man Jud Wilson was.

“His teammates respected him,” Taylor said. “He was a quiet man, but he didn’t play around. There was one story about him where a roommate came in drunk and belligerent one night, and [Wilson] hung him out the window. He got ejected from a game one time because he got blamed for something he didn’t do, and he stood his ground. And if he said he was going to do something, you better believe he was going to do it.”

The ceremony began with 94-year-old Buck O’Neil, the renowned Negro leagues ambassador, giving the introduction — “I’m proud to have been a Negro league ballplayer,” he said — and leading the crowd in a singalong. “The greatest thing / in all my life,” he sang, “is loving you.”

Also honored Sunday were Gene Elston, the longtime voice of the Houston Astros who received the Ford C. Frick Award for broadcasters, and Tracy Ringolsby, the veteran beat writer from the Rocky Mountain (Colo.) News, who received the J.G. Taylor Spink Award for baseball writers.

The crowd was small and subdued compared to recent years, but folks here already are anticipating next year’s ceremony, when the inductees are expected to be former Baltimore Orioles legend Cal Ripken and San Diego Padres right fielder Tony Gwynn. Rental houses for the week of the July 29, 2007, ceremony are being snatched up already.

There was no mention Sunday of the other pressing topic for next year: the first-time candidacy of former St. Louis Cardinals slugger Mark McGwire, and its implications as the test case of the so-called “Steroids Era.”

In fact, there was not an unsavory thought expressed on a day when the sun shone, and Buck O’Neil sang, and Jud “Boojum” Wilson’s perfect nickname echoed across the hills, pronounced just like Satchel Paige once heard it: “Buh-ZHOOM.”

Ernest Judson Wilson (February 28, 1894 – June 24, 1963), nicknamed “Boojum”, was an American third baseman, first baseman and manager in Negro league baseball. Born in Remington, Virginia, he served in World War I, and during his career played primarily for the Baltimore Black Sox (1922-30), Homestead Grays (1931-32, 1940-45) and Philadelphia Stars (1933-39). One of the Negro Leagues’ most powerful hitters, his career batting average of .351 ranks him among the top five players. He also enjoyed remarkable success in the Cuban Winter League in the 1920s.

Jud Wilson

is a member of

the Baseball

Hall of Fame

Wilson got his nickname “Boojum” because that was the noise his line drives made when they hit the outfield walls. Pitcher Satchel Paige claimed that Wilson and Chino Smith were the two toughest outs he ever faced.

Josh Gibson believed that Wilson was a better hitter than he was. Gibson was considered the Babe Ruth of black ball and is in the Hall of Fame at Cooperstown.

Wilson died at age 69 in Washington, D.C. and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Ernest Judson Wilson served in World War I as Corporal, Company D, 417th Service Battalion, Quartermaster Corps.

Jud Wilson

Ernest Judson Wilson (“Boojum”)

Induction Information: Elected to Hall of Fame by Special Committee in 2006, as a Player

- Born: February 28, 1894, in Remington, Virginia

- Died: June 24, 1963, in Washington, D.C.

- Playing Career: 1922-1945

- Primary Position: Third Base

- Bats: Left Throws: Right

Played For: Baltimore Black Sox, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Philadelphia Stars

atchel Paige named Jud “Boojum” Wilson as one of the two toughest hitters he ever faced, and Josh Gibson considered Wilson the game’s best hitter.

“They all looked the same to me,” said Wilson of Negro leagues and white major league hurlers.

A squat, lefty hitter who could play anywhere in the infield, Wilson was known for his potent bat as a line drive hitter to every corner of the ballpark. His temper and ferocity on the field, also defined his career. After starring with the Baltimore Black Sox for most of the 1920s, Wilson moved to the Homestead Grays, where he captained the formidable 1931 squad. After seven years with the Philadelphia Stars, Wilson returned to the Grays, helping the powerful club to numerous championships in the early 1940s.

Did You Know… that at the age of 49, Wilson hit two triples in one game, and hit .288 at 51 years of age?

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard