No. 979-03

IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Dec 26, 2003

DoD Identifies Army Casualty

The Department of Defense announced today the death of a soldier who was supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Command Sergeant Major Eric F. Cooke, 43, of Scottsdale, Arizona, was killed on December 24, 2003, in Baghdad, Iraq. Cooke was in a convoy vehicle that struck an improvised explosive device. Cooke was assigned to 1st Brigade, 1st Armored Division, based in Ray Barracks, Friedberg, Germany.

This incident is under investigation.

US Army Photo

26 December 2003

TEMPE, Arizona — A former Arizona resident was killed in Baghdad after his convoy vehicle struck a homemade bomb.

Eric Cooke died on Christmas Eve.

He was an honest and disciplined man, loved his country and never questioned the country’s involvement in the war, said his brothers, Cordy Cooke, 44, and Josh Cooke, 38, of Roslyn, Washington.

Three other troops also died in Baghdad on Christmas Eve, and four more were killed in central Iraq on Christmas Day during the bloodiest stretch of violence in the country since Saddam Hussein’s December 13, 2003, capture.

“The U.S. Army did for that boy what I could not have done for him,” said his mother, Georgia Cooke, from her home near Molalla, Oregon. “They turned him into a man and a man among men and that is not a mother bragging.”

As the three brothers grew up in Tempe and Scottsdale, it seemed for a time Eric Cooke was headed down the wrong path. When he was 17, police arrested him for possession of burglary tools.

But the Army changed him. Cooke worked himself through the ranks and earned two college degrees. He also served in Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, where he earned a Bronze Star. He was assigned to the 1st Brigade, 1st Armored Division and was based in Ray Barracks, Friedberg, Germany. There, he met his wife of 23 years, Dagmar.

Cooke was an accomplished leader and reached one of the Army’s highest noncommissioned ranks — command sergeant major.

His father, Cord Cooke, 63, of Mesa, hadn’t spoken to his son in more than a decade when he received word of his son’s death Friday.

The last time they talked, Eric called him from a satellite phone from Iraq while fighting in Desert Storm. Cord Cooke said he just drifted away from his children, but time and distance hasn’t diminished the love he had for his son.

“I’m really proud of him, always have been,” Cord Cooke said. “He came from behind and did well.”

Eric Cooke will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in two weeks.

“He was proud to be a representative of the U.S. government on foreign soil most of his life, and I will be proud to represent the Cooke family at Arlington National Cemetery,” Georgia Cooke said.

27 December 2003

TEMPE, Arizona — A soldier who grew up in Arizona was killed near Baghdad after his convoy vehicle struck a homemade bomb.

Command Sergeant Major Eric Cooke, 43, was one of three troops who died the day before Christmas while traveling in a convoy near Samarra, a town north of Baghdad where insurgents have often launched attacks, the Defense Department announced Friday. His mother lives in Oregon.

Cooke was an honest and disciplined man, who loved his country and never questioned the U.S. involvement in the war, said his brothers, Cordy Cooke, 44, and Josh Cooke, 38, of Roslyn, Washington.

As the three brothers grew up in Tempe and Scottsdale, it seemed for a time Eric Cooke was headed down the wrong path. When he was 17, police arrested him for possession of burglary tools.

But the Army changed him. Cooke worked himself through the ranks and earned two college degrees. He reached one of the Army’s highest noncommissioned ranks — command sergeant major.

Cooke also served in Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, where he earned a Bronze Star.

“The U.S. Army did for that boy what I could not have done for him,” said his mother, Georgia Cooke, from her home near Molalla, Ore. “They turned him into a man and a man among men and that is not a mother bragging.”

Cooke was assigned to the 1st Brigade, 1st Armored Division and based in Ray Barracks, Friedberg, Germany.

It was there that Cooke met his wife of 23 years, Dagmar.

His father, Cord Cooke, 63, of Mesa, hadn’t spoken to him in more than a decade when he received word of his son’s death Friday.

The last time they talked, Eric called him from a satellite phone from Iraq while fighting in Desert Storm. Cord Cooke said he just drifted away from his children, but time and distance hasn’t diminished the love he had for his son.

“I’m really proud of him, always have been,” Cord Cooke said. “He came from behind and did well.”

Eric Cooke will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in two weeks.

“He was proud to be a representative of the U.S. government on foreign soil most of his life, and I will be proud to represent the Cooke family at Arlington National Cemetery,” his mother, Georgia Cooke, said.

Four more soldiers were killed in central Iraq on Christmas Day during the bloodiest stretch of violence in the country since Saddam Hussein’s Dec. 13 capture.

27 November 2004

Hero’s life not an easy one

Eric Cooke went from an abused and troubled child to a decorated war hero who sacrificed his life for his country. In the process, the former Scottsdale and Tempe resident inspired the lives of others in ways he never experienced as a boy.

His mother, Georgia Cooke, and widow, Dagmar Krause Cooke, were affected most. His death sent his wife back to her childhood home in Germany. After 23 years as an Army wife, she refuses to discuss her husband’s death. With a VIP house at an Army base in Heidelberg dedicated to Eric Cooke’s memory, it’s unlikely she’ll be able to forget.

With the first anniversary of Cooke’s death on Christmas Eve, his mother talked about her second son’s childhood and the pain she inflicted on him during a time she was an alcoholic and he was totally out of control.

Cooke, 43, a Command Sergeant Major, was killed in a convoy near Samara, north of Baghdad, while making rounds to check on his troops. The Humvee he was in was hit by a makeshift ra d io-controlled rocket. Cooke, the top enlisted soldier of the 1st Armored Division’s 1st Cavalry Brigade, died of head wounds 17 minutes later.

Camp Cooke, an Enduring Forward Operating Base camp in Taji, near the northern outskirts of Baghdad, was named in his honor. He is remembered as the consummate soldier, the epitome of what others aspire to be.

It wasn’t always that way. At 13, Cooke was, according to his mother, an alcoholic and in trouble.

“Being raised by an abusive alcoholic mother cannot do other than distort a child’s perceptions,” said Georgia Cooke, 64, an unwed mother when she had sons Cordy and Eric. “I was a ranting, raving child abuser. The abuse I heaped on Cordy and Josh was mental and emotional. Eric was my favorite to abuse physically. I thought nothing of backhanding him up against the wall for the smallest of infractions of my everchanging rules.

“Eric grew up in a dysfunctional world. I have made my amends and have been all that a mother should be for a lot of years, but that is not what I gave to (him) in the days he most needed it. I gave him fear and resentment and his dropout was as much from the life I granted him as it was from a school that couldn’t meet his needs. His smart brothers only added to his sense of uselessness.”

Georgia Cooke, who lives in Molalla, Oregon, said Eric became a high achiever as an adult. He earned his General Educational Development diploma his first year in the Army and later worked to two degrees. He made the dean’s and commandant’s lists. As boys, his brothers were A-plus students, but Eric hated school, she said. He flunked second grade and was labeled learning disabled.

Cordy Cooke, 14 months older than Eric, didn’t think his brother was a bad child. “He made some bad choices and got in trouble,” said Cooke from his home in Roslyn, Wash., “but he didn’t hurt anyone.”

When he was 14, Eric was sent to live on a relative’s farm in Riverside, California. Back in Tempe in 1978 when he was 17, Cooke hadn’t changed. That April, he went through what his mother called a time “out of hell.”

“Eric was showing all the symptoms of a troubled child acting out his pain and confusion,” she said. “I got a call from Tempe police saying they picked up Eric as a minor in possession of alcohol. The next Friday night the same thing happened. I told him if anything like this happened again, I would dump his poor skinny body into the Army.”

The following Friday, Cooke was expelled from Scottsdale High School for truancy; he considered himself a dropout. His girlfriend of two years dumped him. He went to work in Tempe and was fired. Coming out of his work place parking lot in his stepfather’s Volkswagen, he was in a crash and the car was totaled. That night, he was picked up for alcohol possession again.

Cooke’s stepfather, Cord Cooke of Mesa, said his son wasn’t arrested then because Cooke knew longtime Tempe Mayor Harry Mitchell, now a state senator, who “held up” police action against the boy until he could enlist. Tempe police do not have an arrest record for Eric Cooke.

Sober and in control, Georgia Cooke took charge of her son’s life.

“I got him in the wee hours of the morning (after the incidents) and told him the Army recruiter opened at 8,” she said. “He started crying and admitted he was in trouble and didn’t know how to get out of it. I told him I didn’t really know, but doing nothing was not an option.

“I gave him a choice: Join the Army or I’d kill him. God knows where his life would have been without the Army.”

The military seemed to turn the Phoenix-born Cooke’s life around. He reached one of the Army’s highest noncommissioned ranks.

Command Sergeant Major David Davenport, who lived next to Cooke in Germany and took over his position after he was killed, said his friend didn’t talk much about his childhood. But, Davenport said he pieced together the meaning of some of their conversations after talking with Georgia Cooke.

“He didn’t hide the fact he was in some trouble as a boy,” Davenport said in a telephone interview from Budingen, Germany. “The rowdy teen years didn’t fit the character of the soldier and man I knew. But, I think it made him a good leader. He related well to young soldiers and their problems.”

Cooke also served in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm during the early 1990s and he earned a Bronze Star. He was posthumously awarded another Bronze Star and a Purple Heart.

“The U.S. Army turned him into a man and a man among men,” Georgia Cooke said. “He knew of the dangers of what he did.”

He also came to terms with past dangers.

“Eric had one gift from God that saved his life — forgiveness,” Georgia Cooke said. “Once he was through boot camp, I didn’t hear from him. He was angry with me for putting him in the Army. In the spring of 1979 my sister, the aunt he went to live with, died. I had no idea how to reach Eric and I knew he would never forgive me if I didn’t try. I called the Red Cross and told them to find my boy and tell him there had been a death in the family.”

In less than 12 hours, the phone rang. No one spoke but Cooke heard what sounded like crying. She said “Buzz, is that you?” and waited. “Oh, mom,” came the choked words. “I thought you were dead.” He cried out loud and said “Mom, I love you and I’m so sorry for being a brat. Can you forgive me?”

Georgia Cooke said her son had forgiven her for every fat lip and bruised cheek she inflicted. Cooke’s stepfather didn’t have much contact with him after he enlisted. They last saw each other more than 20 years ago and hadn’t spoken for a decade. Cord Cooke blames Eric’s being stationed in Germany for the lack of contact.

Georgia Cooke said faith and selflessness were keys to her son’s turnaround. He put himself after the nearly 3,000 soldiers under him; he was scheduled for leave on Christmas Eve, but gave the time to another soldier.

“His time was predetermined,” Georgia Cooke said. “He would have died that day, even in his mom’s kitchen. He was supposed to be here 43 years, three months, one day and 12 hours.”

Cooke said she’d talk with her son in that kitchen, or by phone during his deployment. She vividly recalls a 3:30 a.m. call while he was stationed in Saudi Arabia.

“He was terrified,” she said. “He said ‘Ma, I’m scared to death about the men I’m going to kill. They have wives, moms and kids. I’m going to damn my soul by killing them.’ I told him ‘thou shalt not kill should really say thou shalt not murder.’ I told him he was not going to murder. Within six hours, they went into action.”

Although Cooke isn’t sure her son would have preferred dying in action, she knew he understood and accepted the possibility.

“He told me he felt the American people would be worth dying for,” she said. Although Cooke is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, his spirt remains alive. “He was the man in my life,” Georgia Cooke said. “I feel abandoned. He continues to inspire me, from the grave.”

So much so that Cooke wants to work in Iraq. “If I get to Baghdad, I’ll get to Camp Cooke,” she said. “I want to be in the world he was in.”

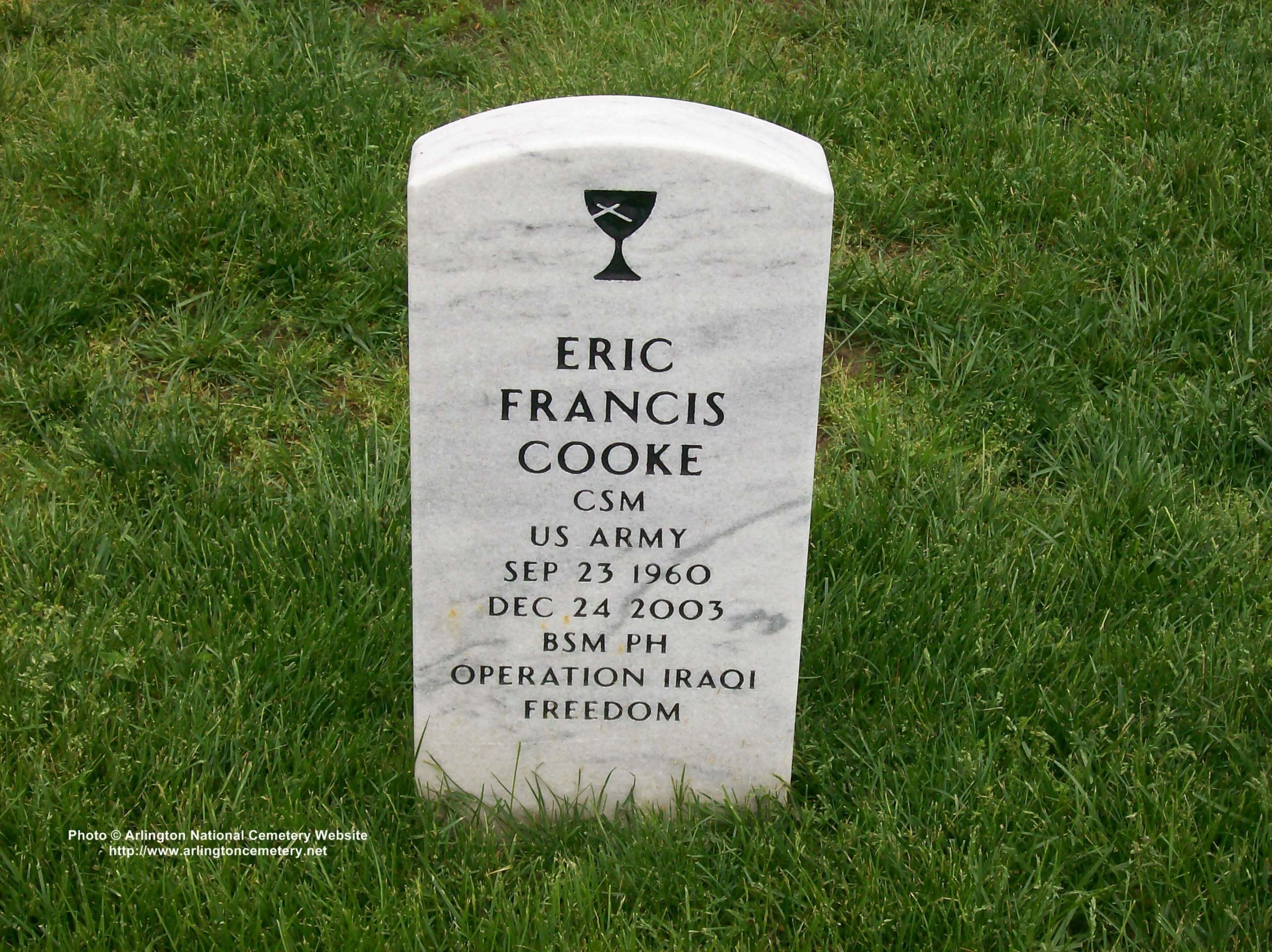

COOKE, ERIC FRANCIS

CSM US ARMY

IRAQ

- DATE OF BIRTH: 09/23/1960

- DATE OF DEATH: 12/24/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8123

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard