Courtesy Of The Pentagram (Friday, January 17, 1997)

A newly honored Medal of Honor recipient was laid to rest for a second time, Tuesday — this time among rows of the nation’s war heroes in Arlington National Cemetery. Soldiers of the 3rd U.S. Infantry (The Old Guard) rendered full military honors.

The January winds that swept across the cemetery chilled those gathered to honor the memory of Staff Sgt. Edward A. Carter II as the caisson came to a halt a short distance from the grave.

Using slow, precise movements, the eight pallbearers moved the flag-draped casket from the caisson to its position at the grave, while all soldiers present rendered hand or rifle salutes.

Following prayer, the sharp sound of rifle fire cut through the air as a seven-member firing party fired three volleys. At the conclusion of the volleys, the haunting notes of “Taps” sounded, borne by the brisk wind from the opposite direction from the volley.

The pallbearers folded the flag precisely, then passed it to the presenting officer, who in turn presented it to Carter’s widow.

Carter, a World War II veteran, was originally laid to rest in Sawtelle National Cemetery in Los Angeles in 1963. Following the announcement that he was to be awarded the Medal of Honor, however, his family decided to have him reinterred in the most-prominent of military cemeteries.

Carter’s path here was filled with numerous obstacles, as his family recalled recently. His sons said they couldn’t remember him much when they were small because he was gone a lot. He had a history of being gone a lot. The son of missionaries, he left Los Angeles with them when he was about 5 years old and was educated in China, according to his elder son, Edward III. He ran away from home as a teenager and served with the Chinese Army until they discovered he was underage, according to his daughter-in-law Allene, who helped with the family research. From there Carter went to Spain, where he fought on the side of the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War. It was on his return from Spain, after fighting on the losing side, that he joined the U.S. Army, she continued. After basic training he was assigned to Fort Benning, Ga., as a cook. Carter also took his wife, Mildred, and Edward to live there as well.

Before going to Georgia in 1941, Mildred said, her husband instructed her, a Californian, on how to behave in Georgia in order for them to survive. Allene said her father-in-law “years later talked about the segregated units, and the fact that they [white soldiers] felt that the black soldiers should have a mop and a bucket, and that they thought they were only fit to clean up.”

“There were very few activities available to blacks in town during that time,” she added. “They just roamed the streets. There were areas you weren’t allowed to even go in.”

At times whites would beat black soldiers in the streets, she said, and when they fought back, they were thrown in jail, thrown on the chain gang. Usually, she said, it led to a dishonorable discharge. Not Carter, he knew how to play the game, she added. He wanted to stay in the Army, and he knew what to do and how to get around. Edward made sergeant in less than a year, Allene said, and was made mess sergeant of the officers’ club.

Carter’s second son, William, was born during their time at Fort Benning, and William’s wife, Karen, told of something that happened during the short hospitalization. “When William was born, he had very, very red hair. So when he was born, they gave him to a Caucasian woman. It was the governor’s wife,” she said, retelling a story which had only moments before been told to her by her mother-in-law.

“When they brought her [Mildred’s] baby to her, Mrs. Carter recognized that there had been a mistake, but it was at least two days before they [hospital staff] realized it was the wrong baby,” Karen continued.

“His first milk came from the governor’s wife,” she added. “He could have been raised in the governor’s mansion,” Mildred added.

Though the Carter sons remember little of their father when they were small, Edward said “when he was there, we had a good time.” They were both still toddlers when he went off to fight in World War II. After the war, his sons said, whenever he spoke of combat, he would pull up his shirt and begin describing how he got his wounds.

“My understanding is that he took out the enemy camp and gave vital information to our side,” said grandson Corey, briefly describing his grandfather’s action.

“All I knew [before preparations for the medal presentation] of what he actually did that day came from a book my dad gave me a long time ago, a `Green Book’ about black heroes.”

At the White House Monday, the Carter family accepted the Medal of Honor in behalf of Staff Sgt. Edward A Carter II, of Company D, 56th Armored Infantry Battalion, 12th Armored Division. He earned the award for “extraordinary heroism in action on March 23, 1945, near Speyer, Germany. When the tank on which he was riding received heavy bazooka and small arms fire,” according to the citation for his Distinguished Service Cross.

“Sergeant Carter voluntarily attempted to lead a three-man group across an open field. Within a short time, two of his men were killed and the third seriously wounded,” the citation said. “Continuing on alone, he was wounded five times, and finally was forced to take cover.”

“As eight enemy riflemen attempted to capture him, Sergeant Carter killed six of them and captured the remaining two,” according to the citation. “He then crossed the field using as a shield his two prisoners from whom he obtained valuable information concerning the disposition of enemy troops.”

“I’m really happy about it — not just for him, but for the others [other recipients] too — to get their just due,” said Edward III, who accepted the award for his father. “It was a long time coming.

“He went through a lot, but he never complained that he didn’t get the medal or anything like that. He told the war stories, like all of them do, and I just wish he were here to see it. He would have been tickled pink just to see this day.”

“Then he would talk about it,” he concluded, drawing knowing laughter from the other family members, including a broad smile from the sergeant’s widow.

His sentiments were echoed by his younger brother, William, who added, “He was a great man. I just love that man,” as his voice began to break. He said his father liked everybody — didn’t hate anyone — including those he killed in the defense of the country.

by Wayne V. Hall

Pentagram staff writer

Staff Sergeant Edward A. Carter, Jr.

General Order:

Citation:

For extraordinary heroism in action on 23 March 1945, near Speyer, Germany. When the tank on which he was riding received heavy bazooka and small arms fire, Sergeant Carter voluntarily attempted to lead a three-man group across an open field. Within a short time, two of his men were killed and the third seriously wounded. Continuing on alone, he was wounded five times and finally forced to take cover. As eight enemy riflemen attempted to capture him, Sergeant Carter killed six of them and captured the remaining two. He then crossed the field using as a shield his two prisoners from which he obtained valuable information concerning the disposition of enemy troops. Staff Sergeant Carter’s extraordinary heroism was an inspiration to the officers and men of the Seventh Army Infantry Company Number 1 (Provisional) and exemplify the highest traditions of the Armed Forces.

Courtesy of US News & World Report

May 31, 1999

LONG AFTER EDDIE CARTER DIED, the U.S. Army and a grateful nation awarded him America’s highest honor for heroism in combat. That was two years ago, and it seemed at the time that an old wrong had finally been righted. It had, but not entirely. Because there was still a mystery about how his country had treated Staff Sgt. Edward A. Carter Jr. About how a battlefield hero could be broken by the country he served, then banished from his beloved military career like a bum.

About why.

Now, at last, the mystery is ended, the puzzle complete. And if the picture it reveals is not entirely new, it reminds again how a nation consumed by paranoia and misspent passion can consume in turn even those who have loved and served it best. Until just days ago, this much was known about Sergeant Carter’s case: Despite his certified record of heroism killing Nazis on the battlefields of Germany, the Army–on the basis of secret charges of disloyalty that had no basis in fact–denied Carter the right to continue serving his country in uniform. There was no hearing. No explanation. No appeal. Just a cold stone wall. It happened in a very different America, in an America just entering the deep freeze of the cold war, a country where patriots and political hacks pursued homegrown Communists, real and imagined, with the passion of avenging angels.

It was not a good time and place to be Eddie Carter. Besides his race, Carter had lived an outsized life. He had been raised in strange lands, fought in foreign armies. China? The Spanish Civil War? Such entries on his résumé raised questions among the Commie hunters. But at such a time and place, such questions–with no answers, no evidence of wrongdoing, and despite his distinguished Army service–had the power to wound and wound fatally. Banned from the service, Eddie Carter fought on for years, asking only that he be allowed to pursue his love of soldiering. But the soldier’s said no. Eddie Carter was crushed, his heart broken. In 1963, he died in Los Angeles. He was 47 years old.

Clearly, a terrible wrong had been done. But Eddie Carter was not alone in that. Two years ago, when President Clinton presented the Medal of Honor to Carter’s family, he bestowed the same belated honor on six other African-American soldiers whose service in World War II distinguished them as heroes

But Carter’s story was different. Unlike the families of the other veterans who received the medal from the president, Eddie Carter’s two sons and a daughter-in-law he never knew were angry. There were fine words of encomium throughout the White House ceremony. But the words Eddie Carter’s kin needed to hear most were never uttered: We apologize. Edward Carter III, the eldest, recalls the memory vividly . “Honor without honor,” he says, summing up the moment.

THE SEARCH

Which is why the story didn’t stop there. Eddie Carter’s family wanted to know the truth. They wanted to know it even if it burned like lye. And they wanted America to know it, too. Edward III’s wife, Allene, knew the old soldier only from his cards, letters, and family photos. But in her drive to remove the stain from her father-in-law’s name she allowed herself no rest. There were blizzards of demands for records. For hidden files. Using the Freedom of Information Act, she peppered the Army and the FBI for answers. It was a lonely crusade. Friends and government officials urged the family to leave the secrets of the past buried in the past. Allene Carter would hear none of it. Eddie Carter’s life was destroyed by secrets and lies. Only in their exposure could healing begin.

But exposure, as any detective can tell you, takes time. Slowly, painstakingly, paying her own way and working in state and national archives on her vacations from her job as a nighttime 911 supervisor in Los Angeles, Allene Carter assembled the pieces one by one. From a trunk she found in a storage locker she unearthed Eddie Carter’s letters. Seeking answers, he had written to the Army, the Department of Defense, the White House. He pleaded with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the American Civil Liberties Union to champion his cause. From the letters emerges a picture of pain and bewilderment. What dark force had caused his banishment?

The answers were slow in coming. Then, just last month, Allene Carter finally got what she’d been waiting for: 57 pages of documents that constituted the newly declassified counterintelligence file the Army had assembled on Eddie Carter. The contents were breathtaking. The Army opened its file on Carter in 1942, when he first enlisted. It was updated like clockwork right up until he was denied re-enlistment, in the fall of 1949. Carter, it seems, was watched like a cat. His commanders in every unit he served in filed secret reports on him. No detail was unworthy of mention. The magazines he read are noted with care: Popular Science and Popular Mechanics. So, too, the club he joined: the Masons. There are interviews with neighbors and landlords. With bosses on every job he ever had. Even Carter’s father was interrogated.

THE FILE

A summary of the Carter case dated June 4, 1943, listed the following “adverse information” about Sergeant Carter:

1. “Subject reportedly was a member of Abraham Lincoln Brigade, having served for 2½ years with said Brigade in Spain.” True enough, as far as the notation went. A born soldier, Carter had joined the brigade and fought with distinction with it in the Spanish Civil War.

2. “Potentially adverse–Subject is seemingly potentially capable of having connections with subversive activities due to the fact that he spent his early years (until 1938) in the Orient and has a speaking knowledge of Hindustani and Mandarin Chinese.” More true facts–albeit ones unilluminated by any context. Carter’s parents were missionaries, and he was raised by them as a young man in China.

Twice, the record reflects, well-meaning men tried to abort the witch hunt. “In view of absence of any adverse information as result of completed investigation,” an entry dated 1943 states, “it is recommended that case be closed and authority be granted Unit Commander to mark Subject’s service record: ‘Not considered potentially subversive. . . .’ Recommend case be closed.” The recommendation went nowhere. At the end of the Carter file is a single sheet of paper, on Army letterhead, from the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Intelligence. The letter refers to Sergeant Carter and states: “ALLEGATION: Communist Party suspect. SOURCE: 6th Army.” Then this: “Information on the allegation is not reflected in the files of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Department of the Army.” Despite all the Army’s compulsive snooping and file making, in other words, there wasn’t a single damning fact about Carter. Only that letter’s allegation. It was dated Dec. 4, 1950. Carter had been refused re-enlistment more than a year earlier.

There is irony in that. Carter’s fight for justice began in September 1949, after he was told he would not be permitted to re-enlist. Had he seen that piece of paper, he would have known the charge against him. Herbert M. Levy, then a young lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union who took on Carter’s case, explains why: “The pronounced national hysteria about communism,” he says, doomed Carter’s cause. To truly understand, he suggests, a passing knowledge of Kafka is useful. “This was completely indecent,” Levy, now 76, says. “But we were on the path to hysteria. It was guilt by association. It was un-American, but it was being done by the House Un-American Activities Committee.”

THE BEGINNING

To best understand Eddie Carter’s story, it helps to start at the beginning. Carter was born in Los Angeles on May 26, 1916, on a brief visit home by his parents, the Rev. E. A. Carter, a traveling missionary, and Mary Carter, a native of Calcutta. The Carters took their young son back to Calcutta, where he attended grade school. The elder Carter then resettled the family in Shanghai, where young Eddie attended a military school. After his father divorced his mother and married a German national, Eddie ran away from home and joined the Chinese Nationalist Army fighting the Japanese. The father got the son back by revealing the young man’s age: He wasn’t yet 18.

But Carter wasn’t home for long. After hitching a ride on a merchant ship to Manila, he tried to enlist in the U.S. Army but was rebuffed. So he worked his way to Europe on another merchant ship and joined the Spanish Loyalists in their fight against Gen. Francisco Franco’s fascists. Carter’s name appears on the roster of the American volunteer unit that fought in Spain, the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Carter spent 2½ years in Spain, often in fierce combat. Once he was captured and held by Franco’s forces. Somehow he escaped. At the end, in early 1938, Carter was among the Loyalists in the mountains when the line broke and those who could fled across the border to France. Carter, by all accounts, didn’t take up the Loyalist cause out of any particular political bent. He threw in with them for the same reason he joined the Chinese Army: He loved a good fight.

SIGNING UP

After Spain, Carter caught a boat to America. In 1940, he met and began courting Mildred Hoover, the widowed daughter of a well-known black family that kept a boarding house in Los Angeles. On Sept. 26, 1941, Carter enlisted in the Army and was shipped to Camp Wolters, Texas, where he baffled instructors who couldn’t understand how a raw recruit shot near-perfect scores with five different weapons. From Texas, Carter was shipped to Fort Benning, Ga. Less than a year later he was promoted to staff sergeant.

Combat billets for black soldiers were scarce. Army leadership subscribed to a policy that black troops couldn’t be relied on in combat and were best used as service troops in engineering, transportation, or stevedore outfits. So, despite his previous combat service, Carter was assigned as a mess sergeant in the 3535 Quartermaster Truck Company. In 1942, Mildred joined him in Georgia where they were married. In two years, she gave him two sons, Edward III and William, in addition to the two children she had by a previous marriage.

The domestic bliss didn’t last long. On Nov. 13, 1944, Carter and his truck company arrived in Europe and were assigned to transporting supplies to the fighting forces. For three months straight, Carter began every day by volunteering for combat. No luck. By late February of 1945, however, things had changed. The Battle of the Bulge had cut through the Army’s infantry ranks like a scythe. Reinforcements were needed desperately. Army brass appealed for volunteers among black troops.

Carter was among the first chosen. Like the other 2,600 black volunteers, he was forced to give up his rank and become a private. Carter stripped off his sergeant stripes and awaited assignment. It didn’t take long. The 7th Army sent Lt. Russell Blair to collect a platoon of black volunteers. Carter caught his eye immediately. “Eddie Carter was an outstanding soldier,” Blair remembers. “He was always neat and soldierly. There was no malarkey about him. He soldiered 24 hours a day. He was one of the best ones. You bet.”

Things moved fast. Carter’s unit was organized into the 1st Provisional Company, assigned to the 12th Armored Division, then assigned again to the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion. “They gave us some six-by-six trucks, three jeeps, a command halftrack and a maintenance halftrack,” Blair says. “And that’s what we fought our war out of.” Floyd Vanderhoff, the company commander, and Blair, the executive officer, made two decisions right off the bat. They gave Carter his staff sergeant stripes back. Then they made him a squad leader of Infantry.

TO FIGHT

The fighting was at hand. The 12th Armored Division was detached to Gen. George Patton’s 3rd Army, and Old Blood and Guts was salivating at the prospect of beating Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery across the Rhine and punching a hole through the heart of Nazi Germany. Carter was ready. It was the 23rd day of March 1945, and the 12th Armored was on a dash toward the city of Speyer. There was a bridge over the Rhine there, still intact. The 714th Tank Battalion was rolling at the point, Eddie Carter and the other black volunteers clinging to the backs of the 714th’s rumbling Shermans. Suddenly, German antitank rockets were screaming through the air. Machine-gun fire crackled.

Carter and his squad took cover. Ahead was a big warehouse. That’s where the rocket fire was coming from. From the road embankment he’d dived behind, Carter surveyed the scene: the warehouse and open ground, maybe 150 yards, between it and him. The warehouse had to be taken. Carter volunteered. He would lead a three-man patrol. Clambering over the embankment, Carter saw one of his men cut down instantly. He ordered the other two to turn back. Before they could reach the embankment, one was killed, the other wounded. Carter ran on alone. Before he reached the berm surrounding the warehouse, he’d taken five bullets and three pieces of shrapnel. He crawled the last few yards, blood and dirt staining his fatigues.

For two hours, Carter waited. Finally, convinced he was dead, an eight-man patrol came out to make sure. Waiting for his moment, Carter opened up with his .45-caliber Thompson submachine gun. Within seconds, six Germans were dead. Carter took the other two prisoner. Using the two as human shields, he marched back across the open field to his company.

Russel Blair couldn’t believe his eyes. From an observation post he’d established on the second floor of a brewery, he watched Carter and the two Nazis cross the road. Blair wanted Carter evacuated to a medic’s tent so his wounds could be treated. Carter refused. Instead, he climbed the stairs to the observation post and pointed out several German machine-gun nests. Then he turned his prisoners over for interrogation. Utilizing Carter’s information, Blair’s company cleared the road to Speyer. The city was taken in two days.

Less than a month later, Carter reported back to Blair, ready for duty. A few days after that Blair got a telegram from the Army hospital in the rear, reporting that Carter was missing, apparently gone AWOL from the hospital. “We sent word to them that it was OK,” Blair says. “We told them Eddie was back with us and everything was all right.”

With Carter, too. In a letter home, he wrote: “Well, I am on my way back up to the front. I’ll be darn glad to get back; back into the fight . . . Mil, I am in good health except for these bullet holes paining me at times. Maybe I shouldn’t have talked my way out of the hospital so soon. The hospital was OK except for the four walls that just about drove me crazy.”

Carter soldiered on to the end of the war in Germany. In July of 1945, Captain Blair, now commanding Provisional Company 1, signed a recommendation that Carter be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second-highest decoration for valor in combat. The DSC was approved, one of only nine awarded to black soldiers for heroism during the war.

BACK HOME

In 1946, Carter was back in Los Angeles. He and Mildred were sought-after guests not only in black society but white society, too. One of the many invitations they accepted was to a “Welcome Home, Joe” dinner. The headliners were Frank Sinatra and Ingrid Bergman. The chairman for the event was Harpo Marx. The dinner was organized by the American Youth for Democracy, a left-wing political group. One of the sponsors was screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, who would later be blacklisted in the movie industry for refusing to answer questions of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Trouble, already, was in the air.

Carter, meanwhile, made a stab at business, leasing out a wartime landing craft for movie-promotion stunts and fishing trips. But the business went bust and the war-hero scene was fading. Carter decided it was time to get back in uniform. The Army snapped him up for a three-year tour at his old rank. Not long after that, he was promoted to sergeant first class. Things, it seemed, were looking up. The brass chose Carter and two other senior noncommissioned officers to train and organize a new all-black National Guard engineer unit in Southern California. Carter was back in his element.

Almost from the moment he re-enlisted, however, the old questions were raised again. Army counterintelligence investigators came to interview Carter. A series of weekly Army intelligence summaries from 1945 to 1946 show how concerned intelligence agencies were with black communities. One document dated Jan. 5, 1946, looked at the “racial situation” and said, “Tension continues; no major incidents.” It ranked two “sensitive areas” on the West Coast. One was Los Angeles: “Rated as sensitive because of the heavy concentration of Negro workers, unrest in the Los Angeles Harbor area, and current government contract cutbacks.”

Then there was that dinner. An Army intelligence summary dated Jan. 12, 1946, noted that an informer was present and stated: “Quotation of embittered World War II veterans honored at the recent Welcome Home Joe dinner sponsored by the American Youth for Democracy (CP organization) as denouncing the ‘so-called democracy for which they fought’ and saying that they have returned ‘to find America more prejudiced than before, and intolerance at an all-time new high.’ “

Re-enlistment refused. Carter paid no heed. He was proud of his role in training the new all-black engineer company. Near the end of his three-year tour, he was transferred from Los Angeles to Fort Lewis, Wash. His family moved north with him. There was no sign of anything wrong until Sept. 21, 1949, when Carter’s enlistment ended. When he announced his intention to re-enlist for another tour, Carter’s commanders said no. He would not be allowed to re-enlist, they said, without the specific permission of the adjutant general of the Army. Carter was stunned. He paid his own way to Washington and turned up on the steps of the adjutant general’s office to ask why he couldn’t re-enlist. He got nowhere.

Now he was angry. He turned to the NAACP. It bombarded the Army with letters and telegrams. But it got nowhere, either. NAACP lawyers could find no evidence that Carter was being discriminated against because of his race. Carter took his case to the ACLU and staff lawyer Herbert Levy.

In a letter dictated by Carter to his wife, Mildred, Carter told Levy, “I have always been loyal and faithful to the land of my birth. Sir, if I were guilty of being a traitor to my country, would I have traveled at my own expense to the Department of the Army requesting permission to re-enlist? I need help. I ask for justice. This could not be democracy. There must be some mistake.”

By May of 1950, Carter’s spirits were low. In another letter to Levy, Carter said he was enclosing his DSC medal and asked that the next time Levy visited the White House he give it back to President Truman. “In my country’s hour of need, I was in the front lines with a submachine gun in my fist. My reward? A stab in the back. So far I have lost two jobs after word passed around that I had been kicked out of the Army because I was a Communist.”

Levy tried everything. On May 16, 1950, he wrote Defense Secretary Lewis Johnson: “All that Mr. Carter asks is that he be given a statement of the charges against him and a full hearing on these charges. We join in his request. . . . We feel sure that you will agree with us that a man who has served his country so well is at least entitled to a hearing.” This letter, like all others, bounced back to the adjutant general of the Army, Maj. Gen. Edward F. Witsell. He answered Levy’s letter. “A complete and comprehensive review of Mr. Carter’s records has been made by competent Department of the Army agencies,” Witsell wrote, “and it has been determined that his re-enlistment cannot be authorized.”

In a private letter to another ACLU attorney, Levy wrote, on Nov. 29, 1950, that an officer in the adjutant general’s office told him that the Army had “turned down Carter purely on the basis of a directive to do so from the Central Intelligence Agency, which itself did not disclose the reasons to the adjutant general.” No evidence of any CIA directive in the Carter case has surfaced in the papers released to the Carter family.

Herbert Levy was 26 years old when he took on the Carter case. “We never found the reason he was suspect,” Levy says now, 50 years later. “The only two things there were his involvement with the Spanish Loyalists and the Youth for Democracy dinner. If you were associated with a group like that, you were suspected of being a sympathizer, or a ‘Pinko.’ Apparently this thing just took on a life of its own.”

In Tacoma, Wash., Carter got work as a vulcanizer in a tire plant. He and Mildred started breeding registered dogs to keep food on the table and the rent paid. In the summer of 1954, in answer to one of Carter’s letters, Levy said, “Frankly, in view of the obvious scare thrown into the Army by the McCarthy mess, I am even less hopeful than I was in my last letter to you of April 7, 1953, in which I expressed pessimism but would not concede defeat.” In response to Carter’s request, the ACLU lawyer returned the DSC medal, which he had not given Harry Truman, plus copies of all Carter’s records and papers.

In 1955, Mildred and the children moved back to Los Angeles. Carter followed a few months later. He got work as a vulcanizer at another tire factory, in the Los Angeles area. It was hot, dirty work, just one more blow on top of the one he had already suffered in having to move back into his wife’s home. Carter began drinking. By 1958 a family friend, a physician, wrote to Herbert Levy’s successor at the ACLU asking if perhaps the climate in America had changed enough so that Eddie Carter might be allowed to re-enlist. The doctor noted that it would help Eddie and his family, too. The ACLU replied that it saw no reason to believe that the Army would now be willing to change its mind.

Late in 1962, Carter was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died on Jan. 30, 1963, and was buried in the National Cemetery in Los Angeles. That might have been the end, except for a study undertaken by the U.S. Army in 1995-1996 to determine why no black soldiers in World War II had received a Medal of Honor. The study focused on the nine black soldiers, including Edward Allen Carter Jr., who had earned the DSC. A special Army Awards Board panel determined that seven of those DSC recipients, Carter included, should have their awards upgraded to the highest combat award, the Medal of Honor.

Seeking answers. All of this was enough for Allene Carter to swing into action. “There were silences in this family that I didn’t understand, and Eddie Carter and what happened to him was always at the heart of the silence,” Allene Carter says. “When Mildred moved in with us, and all she could talk about was Eddie, and I found the trunk in storage, it seemed like the right time to begin to find some answers to all the questions.”

Most of the answers are spread on the record, thanks to Allene Carter’s bulldog tenacity (“I come from the South Side of Chicago; this is not some soft California person you are dealing with.”). What happened to Eddie Carter Jr. should never have happened in a democratic nation. What happened to him wouldn’t have happened a few years earlier or even a few years later. If the U.S. Army and the United States government would like to say “We’re sorry; we apologize for what happened to Eddie Carter,” the Carter family says it is ready to listen and ready to forgive. And maybe a long-dead hero who now sleeps in Arlington National Cemetery will rest a bit easier.

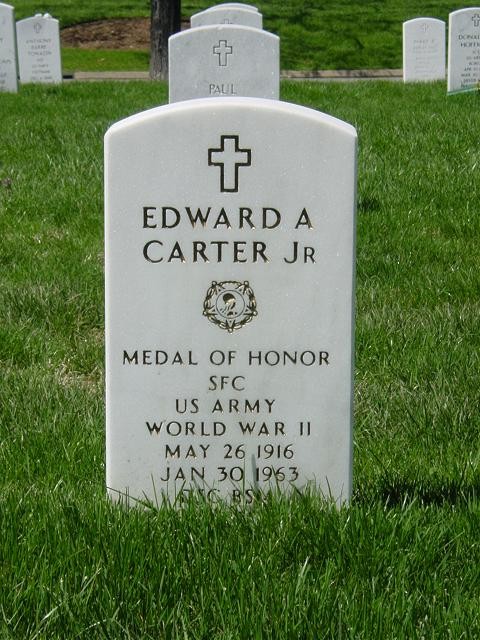

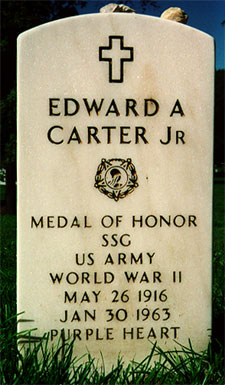

Edward A Carter, Jr.

Born 26 May 1916

Died 30 January 1963

US Army, Sergeant First Class

Residence: Cerritos, California

Section 59, Grave 451

Buried 14 January 1997

Army Apologizes to World War II Vet

November 10, 1999

From a contemporary press report

A half-century ago, Sgt. Edward A. Carter Jr. proved himself an American hero on the battlefields of Nazi Germany, and yet the Army drummed him out of uniform without explanation.

After years of pressure from a family devoted to clearing his name, the Army formally apologized Wednesday for banishing the decorated warrior as a suspected communist and denying him the life of soldiering he dearly loved.

“He was destroyed. Now he has been restored,” Allene Carter, the wife of Carter’s eldest son, said at an emotional ceremony in the Pentagon’s Hall of Heroes, where Carter’s picture now hangs with other Medal of Honor winners. Carter died in 1963 at age 47, months after being diagnosed with lung cancer.

“Today, Sgt. Carter has been vindicated,” Mrs. Carter said.

General John Keane, the Army’s vice chief of staff, presented the Carter family with a set of corrected military records to remove the stain of suspicion that declassified Army intelligence records show had no basis in fact. Keane said he regretted this sad chapter in Army history.

“We are here to apologize to his family for the pain he suffered so many years ago at the hands of his Army and his government,” Keane said, looking out to an audience that included Carter family members and friends as well as World War II veterans. “We are here to say we are sorry.”

“He spent the last years of his life trying in vain to clear his name and to return to the life he loved so well,” he said. “We must acknowledge the mistake, apologize to his family and continue to honor the memory of this great soldier.”

Keane, with Carter’s widow, Mildred Carter, seated at his side, also presented the family with three military awards that a review of his personnel file showed he qualified for but never received. They are the Army Good Conduct Medal, the Army of Occupation Medal, and the American Campaign Medal.

The injustices to Carter were brought to light last spring by U.S. News & World Report, which chronicled a long struggle by Allene Carter to uncover the truth and force the Army to admit its mistake.

“It’s an end to that dark cloud that has been hanging over the family for about 50 years now,” she said in an interview. She and other family members visited Carter’s grave Wednesday at Arlington National Cemetery.

In 1997, Carter and six other World War II veterans became the first black soldiers of that conflict to receive the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest honor for combat heroism. That followed an Army study of why no black soldiers had received the honor. It was not until the U.S. News & World Report story on Carter in May, however, that the other wrongs came to light.

Last August, President Clinton wrote to Mildred Carter to apologize for the Army’s actions.

“Had I known this when I presented his Medal of Honor two years ago, I would have personally apologized to you and your family,” Clinton wrote, referring to the White House ceremony in January 1997. “It was truly our loss that he was denied the opportunity to continue to serve in uniform the

nation he so dearly loved.”

Last spring, Allene Carter received 57 pages of Army documents declassified in response to her Freedom of Information Act requests. The counterintelligence records showed the Army opened a file on Carter in 1942, just months after he had enlisted.

A declassified War Department memo, dated May 8, 1943, said an unnamed intelligence officer at Fort Benning, Ga., where Carter attended infantry school, “deemed it advisable” to put him under surveillance and start an investigation. The reason? The officer had learned he was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, an American volunteer unit that fought against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. The memo said members of the brigade, while “not necessarily communist,” had been

“exposed to communism.”

Also noted in this memo were items deemed “adverse information.” One such item said, “Subject is seemingly potentially capable of having connections with subversive activities due to the fact that he spent his early years (until 1938) in the Orient” and had a speaking knowledge of Chinese.

The declassified intelligence reports show the Army could not find a shred of evidence of disloyalty by Carter.

The son of a traveling missionary who had settled his family in Shanghai, Carter ran away from home and eventually found his way to Europe where he joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

In 1940, Carter came to America and enlisted in the Army a year later.

On March 23, 1945, shortly after arriving on the European front, he found himself on the march with a 12th Armored Division tank battalion near Speyer, Germany, when the tank he was riding sustained heavy fire.

Carter led a three-man patrol 150 yards across an open field toward the Germans’ firing position in a warehouse. Two of his men were killed. Carter was wounded five times. He lay still for two hours until an eight-man German patrol approached him, thinking the blood-soaked American soldier was dead.

Suddenly Carter, though nearly mortally wounded, opened fire with a .45-caliber submachine gun and killed six of the Germans. He captured the two others and used them as human shields to make his way back to his company. His prisoners provided valuable information on German troop movements.

“He was an American hero who was denied the recognition he deserved,” Keane said.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard