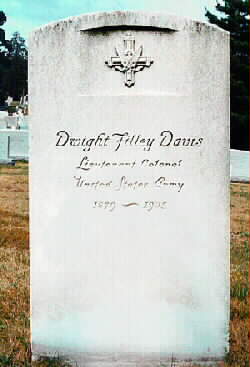

Born on July 5, 1879. He served in the United States Army during World War I and was President Calvin Coolidge’s Secretary of War. He is more famous for the tennis “Davis Cup” which he established and which is named for him.

He died in Washington, D.C. on November 28, 1945 and was buried in Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery.

DAVIS, DWIGHT F.

Major (Infantry), U.S. Army

General Staff Corps, Assistant Chief of Staff, 69th Infantry Regiment, 35th Division, A.E.F.

Date of Action: September 29 – 30, 1918

General Orders No. 9, W.D., 1923

Citation

The Distinguished Service Cross is presented to Dwight F. Davis, Major (Infantry), U.S. Army, for extraordinary heroism in action between Baulny and Chaudron Farm, France, September 29 – 30, 1918.

After exposure to severe shelling and machine-gun fire for three days, during which time he displayed rare courage and devotion to duty, Major Davis, then adjutant, 69th Infantry Brigade, voluntarily and in the face of intense enemy machinegun and artillery fire proceeded to various points in his brigade sector, assisted in reorganizing positions, and in replacing units of the brigade, this self-imposed duty necessitating continued exposure to concentrated enemy fire.

On September 28, 1918, learning that a strong counterattack had been launched by the enemy against Baulny ridge and was progressing successfully, he voluntarily organized such special duty men as could be found and with them rushed forward to reinforce the line under attack, exposing himself with such coolness and great courage that his conduct inspired the troops in this crisis and enabled them to hold on in the face of vastly superior numbers.

Courtesy of Harvard Magazine:

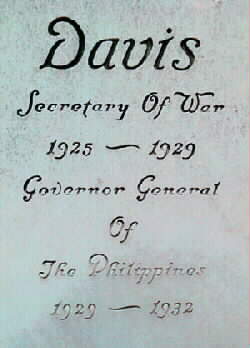

In 1932, the American ambassador in Paris arranged for Dwight F. Davis ’00 to view a session of the Chamber of Deputies. Unfortunately, Davis was seated behind a pillar. His companion appealed to a French official for an upgrade: Davis, after all, had just retired as governor-general of the Philippines. Mais non came the response. But…since the visitor had also been secretary of war under President Coolidge? Another Gallic shrug. The emissary pressed on: This is Monsieur Davis, who gave le coupe Davis, the international tennis trophy the French had held since 1927. Ah, that’s different, said the official, and Davis soon had an excellent seat in front. Years later, when telling the story to a family member, he added, “Now you know what’s important in life.”

This anecdote appears in Dwight Davis: The Man and the Cup, by Nancy Kriplen, published in this year of the Davis Cup centennial. In July, the United States and Australia play a Cup tie (a match between victors in earlier rounds) at Boston’s Longwood Cricket Club, site of the first Davis Cup competition in 1900.

The idea for the International Lawn Tennis Challenge Bowl germinated in 1899, the year Davis won the intercollegiate singles championship after having played the game for five years. That summer, he and three comrades went West to play against some of the best Pacific Coast talent; that fall, American and British partisans thrilled to the America’s Cup races. International sporting contests had already gained prominence with the first modern Olympic Games, held in Athens in 1896. Davis put together the pieces: “If team matches between players from different parts of the same country arouse such great interest and promote such good feeling,” he reasoned, “would not international contests have even wider and more far-reaching consequences?”

Since he came from a family of wealthy St. Louis merchants, Davis had the means to try out his idea. For $750, he commissioned from Shreve, Crump & Low an elegant bowl, 13 inches high and 18 inches in diameter, made from 217 troy ounces of silver. He offered the trophy to the United States National Lawn Tennis Association, which invited Great Britain, then the world’s leading tennis power, to challenge for “Dwight’s pot,” as some Longwood members jokingly called it. Davis also designed the event’s three-day format, which has remained unchanged ever since: two singles matches, on the first and third days, sandwiched around a doubles match.

The British came, and faced an all-Harvard team: Davis, Malcolm Whitman, A.B. 1899, LL.B. ’02, and Holcombe Ward ’00. Davis himself received serve on the very first Davis Cup point. (He hit it out.) Using weapons like the curving, high-bouncing serve that he and Ward had developed–which later evolved into the “American twist”–the Harvardians swept the visitors, 3-0, Davis winning in singles and triumphing with Ward in doubles. When the English returned for a second challenge in 1902, Davis and Ward succumbed to the famed Doherty brothers, but the Yanks dominated in singles and kept the cup.

A news account described Davis as “tall, dark, and keen, without an ounce of superfluous flesh,” and the Crimson once dubbed him the “Harvard Cyclone” due to his “slam-bang aggressive” style. Left-handed and a big server, he thrived on net play and had probably the most crushing overhead of his era. In temperament, Kriplen notes, he was “affable but reserved, formal, earnest, and possibly shy–hardly the daredevil.” But on court Davis took risks, and was either brilliant or erratic. With Ward, he was twice

national doubles champion, in 1900 and 1901; he ranked second nationally in singles in 1899 and fourth in 1898 and 1902.

After college, Davis married and returned to St. Louis, where he was active in civic affairs; as parks commissioner, he helped build some of the nation’s first municipal tennis courts. During World War I, he earned the Distinguished Service Cross for exposing himself to enemy fire in his “self-imposed duty” to gather information for his brigade. He lost a race for the U.S. Senate in 1920, but went to Washington anyway as a director of the War Finance Corporation. His tenure as assistant secretary and secretary of war was marked by controversy over flying ace “Billy” Mitchell’s accusations that the government was neglecting air power, and by his own efforts to improve procurement policies and the mobilization of American industries in the event of war. President Hoover appointed him governor-general of the Philippines in 1929.

Davis continued to play competitive and recreational tennis. In 1923 he was president of the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association; at 57, he won the 1936 national veterans’ (over 45) doubles title. In later years he divided his time between Florida and Washington, D.C., where he chaired the board of the Brookings Institution. (In 1937, when a U.S. team led by Don Budge regained the cup, which had been abroad since 1927, the president of Brookings added, as a postscript to a business letter he wrote Davis, “Rah! Rah! Davis Cup!”) Although Davis never mentioned the cup in his Harvard class reports, the growth of “Dwight’s pot” into the premier trophy of international tennis pleased him. “If I had known of its coming significance,” he said, shortly before his death, “it would have been cast in gold.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard