Career Army Officer ‘Gave Back So Much’

Soldier Slain in Iraq Buried at Arlington

By Theola Labbé

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, June 19, 2003

A lone drumbeat pierced the serenity of Arlington National Cemetery a little after 1 p.m. yesterday, the solemn prelude to the funeral of Lieutenant Colonel Dominic Rocco Baragona.

The 42-year-old Army officer ended his life the way he had lived it, in service to others, family and friends said. Baragona was killed May 19 near Safwan, Iraq, when his Humvee collided with a jackknifed tractor-trailer.

Yesterday the career soldier, West Point Class of 1982, was remembered as a passionate Cleveland Indians fan and as a loving and generous son, brother and uncle, the diplomatic middle child in a family of seven.

Senator Mike DeWine of Ohio, where Baragona grew up, reminded the graveside mourners that Baragona “gave back so much to his family and friends.” He also “gave back so much to his country,” DeWine (R) said.

Known from an early age as “Rocky” — after Indians slugger Rocky Colavito, from whom he got his middle name — Baragona was the glue in his close-knit Italian-Scandinavian family back in Niles, Ohio. At Christmas he relished playing Santa, family members said, spoiling his nieces and nephews with the latest gadgets and planning elaborate gift-giving rituals. One year, a coffee table for his sister could be found and unwrapped only after following a series of clues scattered about the house.

“You almost felt like your presents” were inadequate, recalled his oldest brother, Tony, 47, “because he always bought the top-of-the-line stuff.”

Rocky Baragona brought that good-natured spirit to his military assignments. As commanding officer of the 19th Maintenance Battalion at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, he was responsible for nearly 900 soldiers. The battalion, which supports the III Corps Artillery, was charged with keeping every piece of battlefield equipment war-ready.

When it came to such logistics, said Brigadier General Richard P. Formica, Commanding General of the III Corps Artillery at Fort Sill, Baragona was an unparalleled expert, and an invaluable subordinate.

“I could count on him to tell me what I needed to hear, not what I wanted to hear,” Formica said.

Baragona’s parents, Dominic and Vilma, who have retired to East Point, Florida, sat together on velvet-covered chairs under a canopy yesterday as their son was laid to rest, one of nearly two dozen casualties from Iraq buried at Arlington since the war’s outbreak three months ago. Members of their extended family and friends stood behind them, some sniffling during the prayers and remarks or silently wiping away their tears.

Baragona was divorced, with no children.

Throughout the service, eight soldiers held an American flag over the silver-colored casket, their white-gloved hands never flinching, even when a three-volley rifle tribute crackled through the air. After a bugler sounded taps, the soldiers folded the flag into a crisp triangle for presentation to the officer’s parents. Baragona posthumously was awarded a Bronze Star and a Meritorious Service Medal.

The Baragonas lingered briefly after the official ceremony, holding hands as they approached their son’s casket. Thirty years ago the couple lost a child to leukemia. Now they have buried another.

“When everybody went their own way, he made sure the family stayed together,” Dominic Baragona said of his son. “It’s going to be a great loss.”

BARAGONA, LTC. DOMINIC “ROCKY” (Age 42)

Died May 19, 2003 when a tractor-trailer collided with his humvee near Saffraw, Iraq.

Rocky was born June 14, 1960 in Niles, Ohio, and graduated from John F. Kennedy High School in 1978. He was recruited by West Point and graduated in 1982. He served his country with pride and honor for 21 years and was the Battalion Commander for the 19th Maintenance Battalion based in Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

He is the highest-ranking military officer to have died in Iraq.

He is survived by his parents, Dominic and Vilma Baragona of St. Geroge Island, Florida and five brothers and sisters, Tony Baragona of Pensacola, Florida, John Baragona of Tempe, Arizona, David Baragona of Phoenix, Arizona, Pamela Baragona of Dublin, Ohio and Susan Gunn of Eastpoint, Florida. He is also survived by nine nieces and nephews and four grand-nieces and nephews.

Rocky was preceded in death by a brother, Christopher, in 1974. Services will be held June 18 at 11 a.m. at Arlington Funeral Home, 3901 Fairfax Dr., Arlington, Virginia, followed by a burial service with Full Military Honors at 1 p.m. at Arlington National Cemetery. A reception will be held at 3 p.m. at The Sheraton National Hotel in Arlington for friends and family.

On May 18, 2003, Army Lieutenant Colonel Dominic Rocco Baragona, 42, was in a convoy heading for Kuwait City to load his battalion’s gear on ships. Then the soldiers were to fly home to Fort Sill in Oklahoma.

Baragona found time to e-mail his father, Dominic, in St. George Island, Florida. “Dad, a couple of bullets whizzed by our heads, but we’re now 60 miles south of Baghdad and we’re home free,” he wrote. Minutes later in a conversation by satellite phone, he confirmed to his father that he was USA-bound. “So I asked him, ‘Rock, what’s the worst thing that can happen now?’ ” his father says. “And he said, ‘Dad, something stupid can happen.'”

The next day, near Safwan, a tractor-trailer in the convoy jackknifed and smashed Baragona’s Humvee. He became the highest-ranking U.S. officer to die in Iraq.

“For me to fix blame, it wouldn’t be fair,” his father says. “The only thing I’d kind of like to say is that … I hope all these things they’re lookin’ for, these weapons of mass destruction and other things, I hope they find them. … Then I will feel in my heart that the ultimate sacrifice that he made has some kind of justification.”

A commander of the 19th Maintenance Battalion at Fort Sill was killed in Iraq Tuesday after a tractor-trailer jackknifed on a road and collided with his vehicle, the U.S. Department of Defense announced Wednesday.

Lieutenant Colonel Dominic R. Baragona, 42, of Ohio, died in the accident. He was deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom March 16 with about 100 other soldiers from 19th Maintenance Battalion and attached to Army and Army Reserve units, a press release said.

Baragona was a 1982 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Ordnance Branch. He arrived at Fort Sill in July 2002, officials said.

A memorial service is being planned to honor Baragona.

The accident is under investigation.

No-Show Iraqi Contractor Hit With $4.9M Default Judgment

19 December 2007

When Lt. Col. Dominic R. Baragona died in a traffic accident on an Iraqi highway in 2003, few would have foreseen that his death would prompt a federal judge in Atlanta to levy a $4.9 million judgment against a U.S. military contractor in Kuwait.

Baragona was killed when a tractor-trailer rig owned by Kuwait & Gulf Link Transport Co. struck the Humvee in which he was riding on May 19, 2003, as he was leaving Iraq to return home. He became, at that time, the highest-ranking military officer to die during the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

The legal battle that followed Baragona’s death sought to hold the Kuwaiti company, under contract to the U.S. military, financially liable for the Army officer’s accidental death. Filed by Baragona’s parents, Dominic F. and Vilma Baragona of Florida, on behalf of their son’s estate, the case eventually involved Washington lawyers (one a former staff attorney for U.S. Sen. Ted Stevens, R-Alaska, and the other a former brigadier general in the Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps); the chief investigative judge in the trial of Saddam Hussein who was later spirited out of Iraq for his own safety; and President Bush.

The wrongful death case, which found its way into the federal courtroom of U.S. District Judge William S. Duffey Jr. of the Northern District of Georgia (a former officer in the Air Force Judge Advocate General’s Corps), has become a national case of first impression regarding the responsibilities of a foreign military contractor when an employee’s negligence results in an American soldier’s death, said Steven R. Perles, a Washington attorney who represents the Baragona family.

Perles, a former staff attorney for Sen. Stevens, has an international litigation boutique in Washington that specializes in representing the estates of U.S. citizens killed in terrorist attacks abroad.

During two years of litigation in Atlanta, Duffey established that Georgia was a legitimate venue to seek damages against KGL for Baragona’s death in Iraq. The judge directed a thorough analysis of Iraqi law before he awarded a $4.9 million default judgment to Baragona’s parents after KGL for two years either ignored or failed to accept service of the suit.

“This case is very important and is going to have far-reaching implications,” Perles said of Duffey’s ruling. “It’s the first time any U.S. government contractor has behaved so badly under these circumstances that it had to be sued as a result.”

Defendant Kuwait & Gulf Link Transport Co., which transports supplies into Iraq, is one of the U.S. military’s largest contractors in the Middle East, Perles said. The company, he said, has $100 million a year in Army contracts and also handles subcontracts for military contractors such as Halliburton Inc. and Kellogg, Brown & Root, Perles said.

KGL handles shipping, warehousing and ports management for military organizations worldwide, oil and shipping companies, general contractors and construction firms. In 2006, the company reported revenue of $182.7 million and a net income of $90.7 million, according to BusinessWeek. Since the beginning of the Iraq war in 2003, its annual net profits have nearly quadrupled.

“They are one of three or four contractors who have been the primary beneficiaries of the war,” he said. “Almost every piece of military cargo that lands in the Persian Gulf and is trucked up to Iraq is hauled by this company.”

KGL driver Mahmoud Muhammed Hessain Serour — described as an Egyptian national in his 60s — was driving a tractor-trailer rig on a three-lane highway in Iraq when the truck hit a pile of concrete debris in the right-hand lane and jack-knifed, according to the federal complaint.

At the time, the tractor-trailer rig had drawn alongside a three-vehicle convoy that included Baragona, who was en route to Kuwait and then to the United States on leave, according to the complaint. The lieutenant colonel’s convoy had steered clear of the debris and was traveling in the far left lane. But the tractor-trailer, in attempting to avoid the debris, swerved, jack-knifed, crossed two lanes of traffic and collided with Baragona’s Humvee, the complaint stated.

Baragona was thrown from the Humvee, although witnesses said he was wearing a seatbelt. KGL’s driver survived and was transported to a coalition hospital for treatment before he returned to Egypt. An Army investigation subsequently determined that the driver’s negligence caused the accident and Baragona’s death, according to the complaint.

Perles said that military contractors such as KGL are required by the U.S. government to carry liability insurance. “It’s mandatory,” the lawyer said. “No insurance, no contract.”

As a result, he said, a contractor found to have been negligent normally resolves damage claims through its insurer. “This company was very unusual. It went in the opposite direction,” Perles said. “This kind of temerity among government contractors is unheard of … They told us in no uncertain terms they were untouchable.”

It was KGL’s extensive financial ties from 1997 through at least 2005 via its military contracts with the Army at Fort McPherson that allowed Perles, on behalf of the Baragonas, to establish jurisdiction in Georgia for the litigation. In late 2005, after the case was filed in Atlanta, the Supreme Court of Georgia issued an opinion dramatically expanding prior precedent that had restricted the reach of Georgia’s long-arm statute (establishing jurisdiction over nonresidents in civil litigation who owned property in Georgia or conducted “any business” in the state) to contract claims.

In that case, Innovative Clinical & Consulting Services v. First National Bank of Ames, Iowa, 279 Ga. 672; 620 S.E. 2d 352 (Ga. 2005), the state Supreme Court determined that the Georgia courts have “unlimited authority to exercise personal jurisdiction over any nonresident who transacts any business” in Georgia and that Innovative Clinical overruled all prior cases that failed to offer “the appropriate breadth.”

Duffey subsequently determined that the Baragonas could sue KGL in Georgia.

The key to determining jurisdiction was whether KGL did business in Georgia, Perles said. “My view,” he said, “is that if you do $800 million in business out of Fort McPherson, Georgia, that’s a very significant interaction with the forum.” Those contracts have provided for transport and cargo services for the Third U.S. Army in Iraq, according to a court pleading.

Perles added that if the U.S. Army had discovered that KGL had engaged in any kind of procurement fraud, those charges would have been prosecuted in federal court in Georgia under the terms of the military contracts KGL signed. KGL, he said, “had the expectation that if anything went wrong, they could well be hauled into court here.”

DROWNED IN DUE PROCESS

Despite Duffey’s ruling, KGL ignored the Baragona suit, three times refused service and refused to make an appearance in the case, Perles said. Baragona said that the mechanism set up through the Hague Convention of 1965 on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters to serve foreign court papers, and a second attempt at service through the Kuwaiti Ministry of Justice, failed to prompt an answer from KGL.

Perles said he also sent a consultant to Kuwait to meet privately with officials at KGL. The response, he said, was brusque: “We are a Kuwaiti company. We are untouchable. We are not even going to have a conversation with you. Goodbye.”

Duffey himself became involved in trying to serve KGL’s chairman through the district court clerk in Atlanta after Perles’ lawyer learned that under Kuwaiti law, judges, not attorneys, serve the suits initiating litigation.

Perles said that FedEx delivered the suit from the U.S. Clerk of Court in Atlanta to KGL’s chairman in Kuwait. “The report back from FedEx, ‘We served it. The chairman refused to open it,'” he said.

Perles said that, at Duffey’s request, he also tried to serve the suit on KGL through retired Army Brig. Gen. Richard J. Bednar, now senior counsel at Crowell & Moring in Washington. But Bednar, who did not enter an appearance in the federal case in Atlanta, refused service, Perles said.

Bednar was served with the Baragona suit at Duffey’s suggestion after KGL’s director of legal affairs suggested in a 2006 letter to the Army’s procurement fraud branch that Bednar was providing counsel to KGL, according to Perles.

“When this company ignored service, Judge Duffey went a long way out of his way to give them actual notice of the proceedings,” Perles said. “Much more than the law required him to do. It was an exercise in drowning someone in due process.”

Duffey eventually entered a default judgment against KGL, but not before Perles said the judge began, in the absence of a defense, to raise issues that the defendants themselves might have raised had they participated in the litigation.

“The effect of that was rather than conduct an ordinary default, we conducted a trial in absentia,” Perles said, with Duffey “doubling as judge and adversary … By being both judge and adversary, he forced us to craft what I think is a really bullet-proof proceeding.”

As a result, Perles said, “It’s going to be much more difficult for KGL to try to get this [judgment] set aside than if it had been treated as an ordinary default.”

Perles said that Duffey also required him to provide the court with an analysis of Iraqi law and whether conflicts existed with Georgia law regarding the Baragona family’s negligence claims against KGL.

UNDERSTANDING IRAQI LAW

Duffey eventually determined that five days before Baragona was killed in Iraq, the Coalition Provisional Authority had declared itself to be the governing authority in Iraq. At that time, the provisional authority declared that the laws then existing in Iraq remained in force, which, the judge concluded, included the law of civil damages that would apply to the Baragonas’ claim, according to one order.

That section of the Iraqi Civil Code provided that “every person has the right of passage on the public road provided he (observes) the safety (precautions) so that he will not cause injury to a third party ..”

“Although there was a period of significant unrest and confusion between the fall of Saddam Hussein and the rise of the CPA [Coalition Provisional Authority], this unrest indicates a breakdown in enforcement, not the absence of laws,” Duffey wrote. “The Court understands the CPA regulation to adopt Iraqi civil law as it existed under Saddam Hussein at the end of his reign.”

But Duffey also required the plaintiffs to determine whether Iraqi law permitted the recovery for wrongful death as well as injury, permitted the parents of the victim to recover those damages and established any parameters for damage awards. To answer those questions, Perles said he recruited Judge Raid Juhi Hamadi Al-Saedi, the chief investigative judge for the Iraqi High Tribunal who referred the first cases against Saddam Hussein to the adjudicating court in Baghdad that led to Hussein’s death sentence and execution.

Perles also enlisted the aid of Dr. Abdullah F. Ansary, a Saudi professor of law with degrees from Harvard University and the University of Virginia School of Law. The two Iraqi legal scholars agreed that Iraqi law permitted damages for wrongful death, permitted recovery by the parents, particularly the mother, of the deceased, and gave the court wide latitude in ascertaining damages, according to court filings.

The two scholars also noted that the Iraqi courts, like the Georgia courts, may hold employers liable for damages from injuries caused by their employees’ negligence, according to their report.

Following a damages hearing in April, Duffey established that the economic loss from Baragona’s death ranged from $3.9 million to $8.1 million, according to one order. Duffey settled on $4.9 million.

ENFORCING THE JUDGMENT

Perles said that even though KGL is in Kuwait, and has, so far, failed to participate in the litigation that ended in the judgment, he believes he will collect from the Kuwaiti firm. Perles said that KGL has also become the subject of a federal inquiry by the U.S. Army stemming from a private meeting that President Bush had with the Baragona family after their son was killed.

Military contractors may be barred from doing business with the federal government, including its military branches, for fraudulent misconduct, violation of antitrust statutes, dishonesty or a lack of integrity, according to the JAG Corps Army fraud fighters Web site. Debarment — which may be based upon a criminal conviction, a civil judgment or a preponderance of the evidence — severely restrict the ability of a company to be considered for government contracting business for as long as three years.

Perles said that the Baragonas, who were living in Ohio when their son was killed, appealed to then-U.S. Sen. Mike DeWine, R-Ohio, for help. On the Baragonas’ behalf, DeWine filed complaints with the U.S. State Department and Kuwait’s ambassador to the United States, whom he met at a U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee coffee.

After the Kuwaiti ambassador gave DeWine “the brush-off,” Perles said DeWine complained to President Bush, who arranged to meet with the Baragonas while on a swing through Ohio. At that meeting, at a local Wendy’s, the Baragonas told the president that KGL had stonewalled them and asked him to initiate debarment proceedings against the military contractor, Perles said. The president promised the family he would, and then did so, Perles said.

On Sept. 22, 2006, the chief of the Army’s procurement fraud branch issued a show-cause letter to KGL as to why it should not be debarred from doing business with the Army command, according to court documents.

In an Oct. 18, 2006, reply that is included in court files in Atlanta, Ahmed Afifi, director of legal affairs at KGL in Kuwait, asserted that KGL and firm Chairman Saeed Esmail Dashti “strongly disagree” with allegations made in connection with the Atlanta litigation. The letter insisted that neither KGL nor its executive had ever “taken steps to frustrate the lawful delivery of court documents in connection with that lawsuit” and that the Baragonas’ attempts to serve the suit on KGL had been flawed.

“KGL would like to assure your office that KGL did not frustrate or delay the lawful service of the relevant court documents,” Afifi wrote, adding that conforming KGL’s “conduct to its national and international law regarding service of process is not a basis to consider debarment proceedings … In the meantime, KGL will continue to support the government of the United States of America and its representatives overseas.”

Afifi referred all further questions to Bednar, the Army’s former chief debarment officer, according to his letter.

Last week, Bednar said he is not currently doing any legal work for KGL. He said that he did look into the matter after the Army issued its show-cause letter complaining about KGL’s apparent refusal to accept service of the suit. “I wrote back and explained there was a flawed attempt to deliver [the suit] in Kuwait … We provided information on how it could be perfected … That was the only issue on the table.”

“As far as I know, that matter is closed,” Bednar added. “I answered the letter. We’ve never heard back … There was never a debarment proceeding. The company was never suspended. It was never proposed for debarment. It was never debarred.”

Bednar said that other than the show-cause letter, he didn’t recall whether KGL has been a client. “I have hundreds of clients,” he said. If he has done work for KGL, “it was not very extensive.”

Perles said that after the Army issued the show-cause letter, it asked him to agree to a voluntary suspension of debarment proceedings until after Duffey decided the case. Perles agreed. After the judgment, the lawyer said he notified the Army of Duffey’s decision. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s [the debarment inquiry against KGL] open.”

Perles said that if KGL faces the loss of its government contracts through debarment, it might consider paying the Baragonas’ outstanding judgment as a way of mitigating any formal action by the Army. “If a government contractor engages in conduct that makes them unfit to be a contractor … the hearing officer looks at all of it, including whether a contractor makes restitution,” Perles said.

Perles said that he cannot lay claim to monies that the U.S. government may owe to KGL. But he may seek to attach funds that KGL is owed by American firms such as Kellogg, Brown & Root, under which KGL has subcontracted military business.

“I can’t attach government funds sitting at Fort McPherson,” he said. “If KGL got its money in Kuwait, via direct wire, I have no way of getting that. But if Fort McPherson gives Kellogg, Brown & Root another contract … once it [the money] hits Kellogg, Brown & Root I can attach it … We will find out where KGL does subcontracting, and we will issue writs of attachment. This judgment is going to get enforced.”

The case is Baragona v. Kuwait & Gulf Link Transport, No. 1:05-cv-1267 (N.D. Ga.).

KGL, Iraq Contractor, May Avoid $4.9 Million Fatality Verdict

By Laurence Viele Davidson and Tony Capaccio

Courtesy of Bloomberg.Com

9 January 2009

A federal judge has said he may be forced to render an “injustice” and cancel his order telling a Kuwaiti military contractor in Iraq to pay $4.9 million to the family of a U.S. Army officer killed in a road accident.

The contractor, Kuwait & Gulf Link Transport Co., is asking U.S. District Judge William Duffey in Atlanta to throw out the 2007 default judgment, arguing he lacks jurisdiction over the foreign company for a wreck that happened overseas.

Duffey’s remarks at a December 5, 2008, hearing suggest he is leaning in that direction, said an attorney for the family of deceased Lieutenant Colonel Dominic Rocco Baragona. The judge might rule at any time.

“I think what the defendant has done here is ghastly,” the judge said, referring to the Safat, Kuwait-based trucking company, according to a transcript of the hearing. “I’m going to interpret my law and my Constitution the way my courts tell me that I should, even though in the bottom of my heart I might think that I am ultimately working an injustice.”

Steve Perles, a Washington lawyer representing the Baragona family, predicted his clients will lose.

“Duffey is sending a strong signal that he’ll do what the law requires whether he finds the company’s actions morally repugnant,” Perles said January 5, 2009, in an interview.

Cliff Zatz, a lawyer for KGL with the Washington law firm Crowell & Moring, declined to comment, saying the company hadn’t authorized him to speak publicly.

The Army is reviewing the case to determine whether the company should be barred from bidding for U.S. military contracts.

KGL has a contract to transport supplies for the military in Iraq. It provided the largest quantity of heavy equipment transporters and flatbed trucks to contractor IAP Worldwide Services in support of the U.S. surge in 2007, it said on its Web site.

Baragona, 42, died May 19, 2003, two months after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, at the Iraq-Kuwait border. The Humvee in which he was riding on his way home on leave collided with a tractor- trailer driven by a KGL employee, according to the family’s complaint and an Army accident report.

The truck struck a pile of debris, jackknifed and crossed the road into the military vehicle, the Army report said. The KGL driver was at fault, the family said, citing the report.

The Baragonas sued in Atlanta because nearby Fort McPherson is headquarters for the Army’s Central Command, which contracted with KGL. The family won a default judgment because the company didn’t appear, and the court didn’t determine whether KGL’s driver was at fault.

The company first responded to the 2005 lawsuit last February after Duffey ordered the payment. KGL asked the judge to cancel his ruling and dismiss the case for lack of jurisdiction.

At the December hearing, company officials testified they never did business with or received any money or paperwork from Fort McPherson.

“All of the contracts were issued, administered, performed and paid in Kuwait,” KGL said in court papers.

The case drew the attention of members of Congress and the White House. The Bush administration in 2006 asked the Army to review whether the company should be barred from receiving U.S. contracts. Two U.S. senators in October asked the Kuwaiti government to urge KGL to pay the damages.

An Army fraud unit in Arlington, Virginia, is monitoring the case to see if there are grounds for a debarment proceeding against KGL, said David Foster, an Army spokesman.

Military authorities in December told KGL to prove it has liability insurance as it’s required to, the Army said.

The Baragona family received $250,000 in military insurance for the soldier’s death, his father, Dominic Baragona, said. They are using the money to award high-school scholarships, he said.

The family, resigned to a court loss, still is fighting to get KGL banned from contracting with the government and will meet with congressional staffers next week, Baragona, 75, said yesterday.

“We are not going away,” he said. “That’s what the Rock would do for us.”

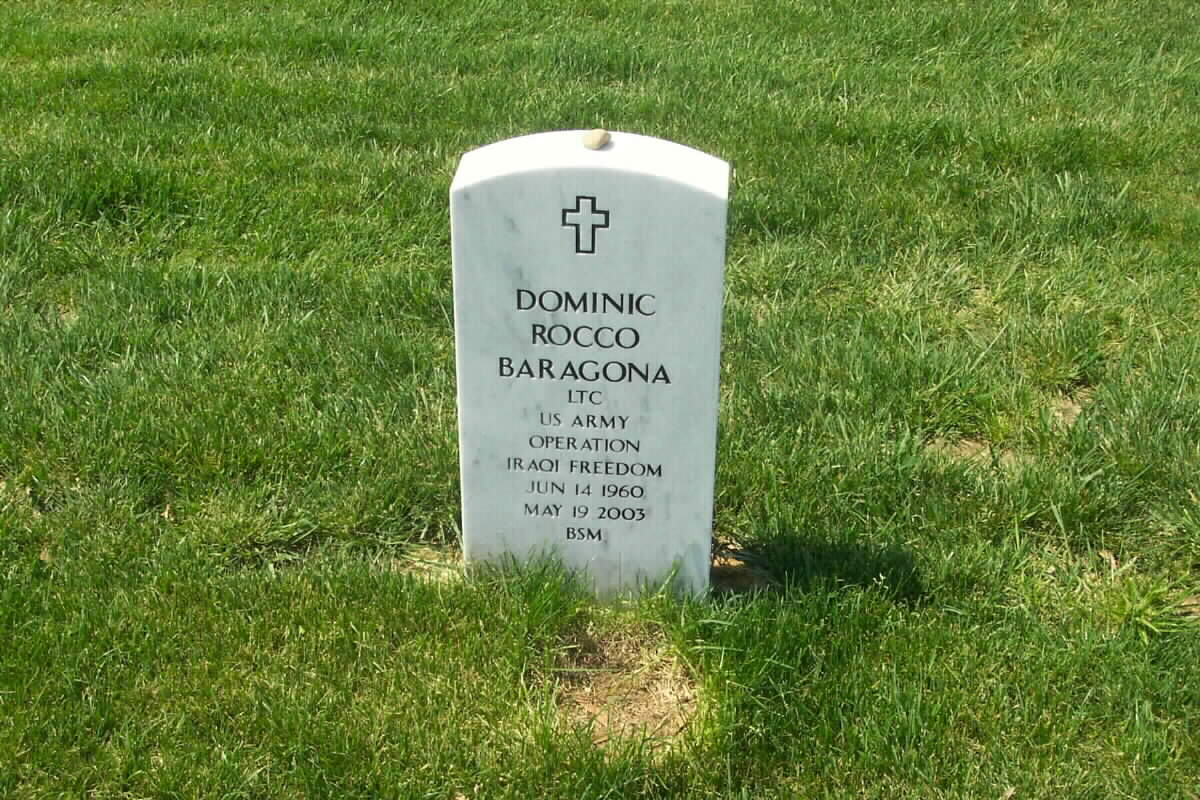

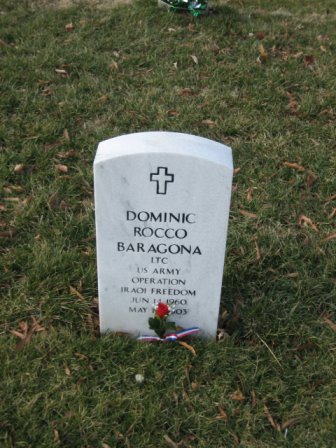

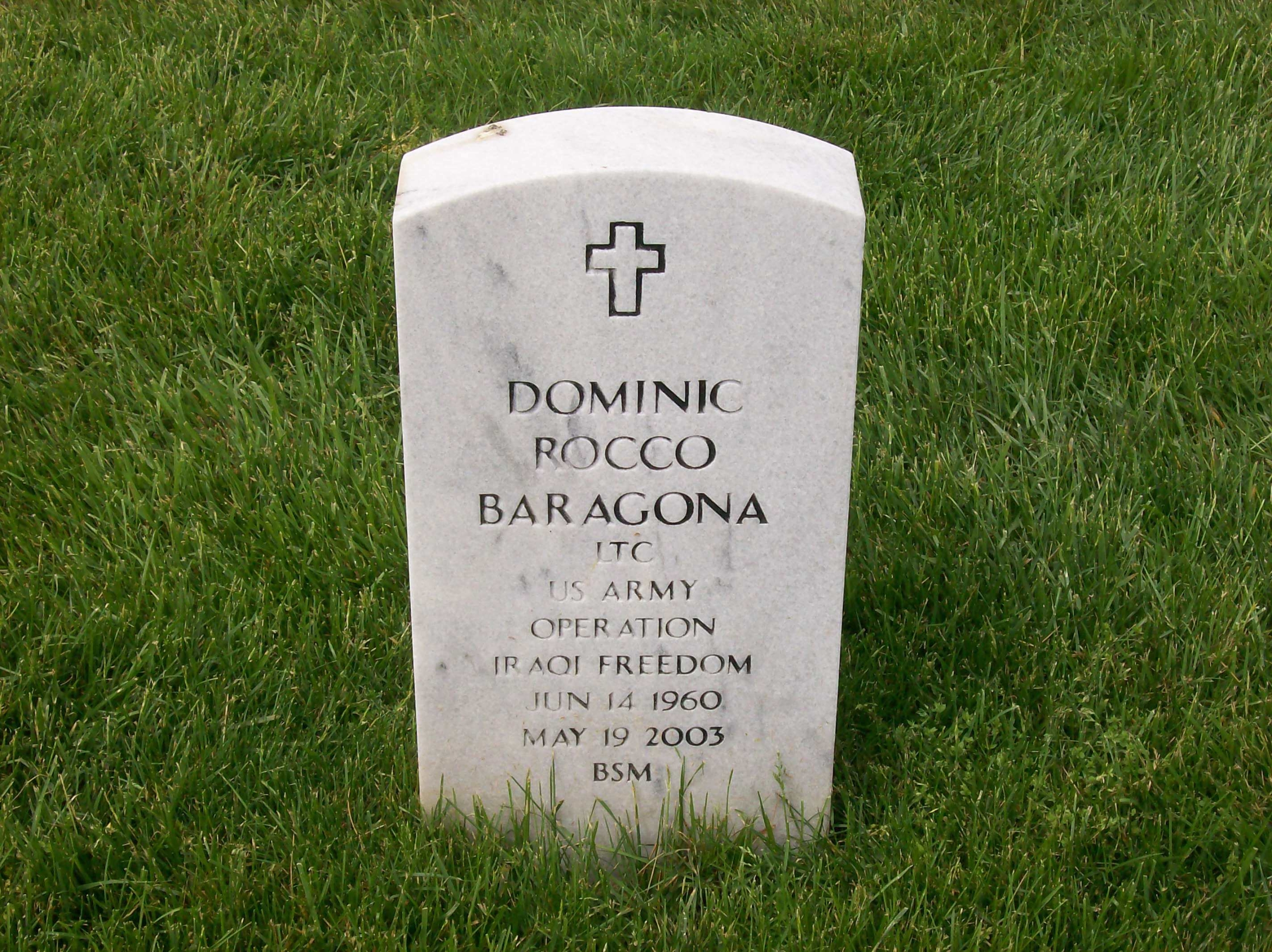

Baragona is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The case is Baragona v. Kuwait Gulf Link Transport Co., 05- cv-1267, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Georgia (Atlanta).

BARAGONA, DOMINIC ROCCO

- LTC US ARMY

- IRAQ

- DATE OF BIRTH: 06/14/1960

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/19/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7881

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard