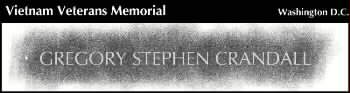

A tooth belonging to US Army Warrant Officer Gregory S. Crandall was buried in a full-size steel casket with full military honors September 17, 1993 at Arlington National Cemetery. The family of Warrant Officer Crandall, who at age 21 was shot down in a helicopter over Laos on February 18, 1971, vehemently objected to the burial and tried to stop it.

“A single tooth does not a death make,” said his sister, Nancy Gourley of Kenai, Alaska. “We don’t feel a single tooth validates a death … Anyone can lose a tooth.” His tooth was one of four teeth or parts of teeth recovered at a crash site in a jungle in Savannakhet province, Laos, in February 1991 during a joint US-Laotian excavation effort. His dog tags had been found at the site nine months earlier.

John Manning, chief of the Army’s Mortuary Affairs Branch, said witnesses of the 1971 crash reported that the helicopter burst into flames and exploded when it hit the ground. But Crandall’s relatives said they reject the military’s finding of death in his case, noting that no other human remains were recovered from the crash site.

Mrs. Gourley and other family members, including her mother and two sisters, attended the funeral yesterday under protest. The funeral should not have been held “until the family feels resolved in our hearts and minds [that Warrant Officer Crandall is dead] and we’ve received the fullest possible accounting,” Mrs Gourley said. “But the government told the family that it was going to bury Crandall with or without them,” said J. Thomas Burch Jr., chairman of the National Vietnam Veterans Coalition, consisting of 73 independent Vietnam veterans groups representing a total of 350,000 veterans. He said Mrs Gourley approached Defense Secretary Les Aspin at POW Recognition Day ceremonies last week and asked him to stop the funeral. “She also tried to get into the Rose Garden [on Thuraday] to ask President Clinton to stop it,” Mr Burch said.

Unable to stop the funeral, the family sent out protest burial announcements. “The family of Warrant Officer Gregory S. Crandall regrets to announce the burial of a single tooth as his remains at Arlington National Cemetery on September 17 at 1 p.m. Your attendance is welcome,” the announcements read.

Mrs Gourley said her family does not dispute that the tooth excavated from the “bomb crater” is Crandall’s. “We’ve never contested the validity of the identification of the tooth … There was a radiographic match,” she said, adding that her family needs more evidence than a tooth and a dog tag to be convinced of Crandall’s death. The Army insists the tooth is not the sole proof of the helicopter pilot’s demise. “There were several eyewitnesses to the crash,” Mr Manning said. The witnesses reported that the helicopter – which was carrying two others besides Crandall – burst into flames under gunfire and crashed and exploded in the jungle.

“They said there was no possibility of survival, and in May 1971, Crandall’s family was told he was dead,” Manning said. Mrs Gourley said her family is suspicious of the Pentagon’s findings because only teeth were excavated from the crash site and a like-new nylon name tag was found at the base of the crater. Manning said the name tag belonged to one of the other two passengers in the helicopter. Noting Laos’ tropical climate, Mrs Gourley said “water would have filtered down through that name tag. I live in Alaska. But you couldn’t put a name tag in the cold ground of Alaska for 20 years and have it survive like that.”

Asked about the few remains at the site, Maj Roger Overturf, spokesman for the Joint Task Force for a Full Accounting of MIAs and POWs, said “a paucity of remains is the norm, rather than the exception to the rule.” As for the name tag, the major said its condition is not unusual. “You have to separate organic remains from inorganic remains. On a number of occasions, we have found laminated ID cards at sites. These were cases where everything indicated [the aircraft] blew up or burned up in a fire. But the laminated ID card was found – with its edges singed – but otherwise in perfect condition.” But Mr Burch said: “I think the family has legitimate concerns. It’s one thing if you have a full skeleton of someone. But when the government as something as insignificant as one itsy-bitsy tooth, and the family doesn’t want to accept it [as evidence of the soldier’s death], we have problems with them ramming it down their throats.”

The Defense Dept provided up to $2,000 for yesterday’s burial and placed a headstone for Warrant Officer Crandall at the grave. “We said we’d absolutely delay the ceremony if the headstone’s not there,” Mrs Gourley said.

When he was an 11 years old, Gregory Stephen Crandall wrote a fictional account of 3 Army soldiers who died in battle making sure their friends made it out alive. “The company had been saved,” the young boy wrote. “Saved to come back and pick up their sacred bodies.”

When he was a 21-year-old Army helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War, he was one of three soldiers shot down over the jungles of Laos. But now, after two decades in which he was listed as “killed in action, no body recovered,” the US Army is bringing him back. Friday afternoon, under full military honors, the human remains belonging to Army Warrant Officer Crandall will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery. And while it may close the long years of uncertainty over his fate, it also is opening new anguish for his family who still cannot accept that he is dead. For inside the flag-draped coffin will be all that was found of this soldier: one single tooth.

“I’m either going to lose my sanity or lose control of my anger,” said Nancy Gourley, who has spent 23 years hoping to settle the mystery of her older brother’s disappearance. She and other family members do not believe that one tooth proves anyone is dead. They also wonder about a process under which the US government paid the Laotians and were then granted permission to survey the old crash site, mysteriously finding certain key evidence with ease. Crandall’s dog tag was lying above the surface, and four teeth – at least one from each missing man -were found below ground, but there was not a trace of other remains: No skulls, bones or even bone fragments. But Pentagon officials insist he is dead, and say the burial is fitting for military honor and propriety.

“Whatever we can recover of the soldier, we take very seriously our obligation to bring him home,” said Shari Lawrence, an Army spokeswoman. Disputes between the Pentagon and families of missing American servicemen from the Vietnam War are hardly new. The arguments are familiar, the accusations rote. Yet unlikely as it might seem, the dispute over Gregory Crandall’s No. 4 maxillary premolar and other still unresolved cases are exposing new fissures in the debate, this time dividing the usually like-minded national support organizations for Vietnam veterans and their families. The questions revolve around the exhaustive, $100 million-a-year Pentagon effort to excavate old battle sites in Southeast Asia in an effort to find and bring home the fragmentary remains of American war dead.

The US government is negotiating with Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia for any new precious information that could lead to crossing out the name of yet another soldier on the list of the 2,250 still unaccounted for. Earlier this week, President Clinton refused to lift a trade embargo against Vietnam, saying its leaders must do more to settle the issue of missing US servicemen. And at a Pentagon ceremony for the national POW/MIA Recognition Day last Friday, Defense Secretary Les Aspin pledged: “Today, we are at work around the world trying to resolve that uncertainty.”

Of the national support organizations, some believe the US effort should be more vigorous, forcing Vietnam to turn over more records of Americans. “The Vietnamese have never been known to let go of anything,” said Ann Mills Griffiths, executive dir of the National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia. “That’s why they continue to dole out tiny bits of information.”

Others, however, want the US to abandon the tedious hunt for remains, and concentrate instead on the living who may still be held prisoner there. “If we’ve got plenty of time to sift through the dirt to find old bones, why not put that same emphasis into the live sightings?” asked J. Thomas Burch Jr, a Green Beret in Vietnam and now a Washington, DC lawyer and chairman of the National Vietnam Veterans Coalition. He and others consider it absurd for the government to close out the search for a missing servicemen on the strength of just 1 tooth, or as in other cases, a bit of an arm bone or a leg.

It is to this divided capital that the remains of Warrant Officer Crandall return this week. In February 1971, Crandall’s helicopter was shot out of the sky and, after a series of seven explosions, crashed into an old bomb crater. Twenty years later to the month, a US recovery team was granted access to the crash site. Among the items found: Crandall’s dog tag; 4 teeth; a name tape of “Engen” belonging to Specialist 4 Robert J. Engen, also aboard the helicopter; and the name plate from the helicopter, built in Culver City, California. Mysteriously, the dog tag was found lying atop the surface, despite 2 decades of tropical weather and monsoons in heavy terrain. Equally odd is that only the helicopter name plate, and no other major aircraft parts, were found. And while the teeth were covered, there were no skulls or other skeletal parts. Crandall’s sister, Gourley, finds it equally astonishing that before the US military gained access to the site, the American government agreed to build a school in Laos and provide other economic assistance, raising her suspicion that some of the material could have been “planted” at the crash site by Laotians eager to make the arrangement pay off for the US, possibly encouraging more US assistance in the future.

“The Defense Department has no right to force this on our family,” she said. “We only want to leave his case file open until we feel positive that Greg is dead.” If the tooth was planted, the disturbing likelihood arises that Laos is holding back Crandall’s other remains, or possibly keeping him alive and hidden in a prison camp.

Major Steve Little, a Pentagon spokesman who specializes in the MIA issue, acknowledged the possibility always exists that remains have been tampered with by the governments in Southeast Asia. He said that situation puts the US in a precarious position of “having to use whatever means are at our disposal” to not only identify what bones are found, but also to positively discount a potential hoax.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard