Lieutenant Charles Gatewood is almost lost to American history, but was recently revived somewhat by the movie “Geronimo,” in which he was a central character.

A graduate of West Point in 1877, he was posted to the Cavalry in the West, eventually serving under Brigadier General Nelson Appleton Miles in Arizona and New Mexico. After forces serving under Miles were unable to capture Geronimo and his small band of Indians, Gatewood (who had put a lot of work into learning the ways of the Indians – including their language) was given the task of proceeding into Mexico and convincing Geronimo to surrender to Miles. This job was successfully carried out, but Gatewood ran politically afoul of Miles when he (Gatewood) began to get too much of the credit for the capture of the great Indian chief. He was banished to service with the Cavalry in the Dakotas.

There he participated in keeping the peace between rival factions of ranchers. He was badly injured in these efforts and was moved, on sick leave, to Washington, DC. At that time he was the senior Lieutenant in the 6th United States Cavalry and the 8th ranking Lieutenant in the entire Army.

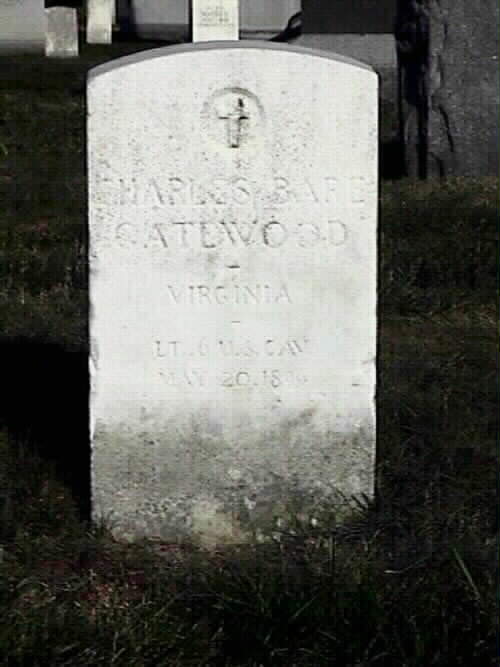

After returning to Washington he began suffering from painful stomach pains and was transferred to the Army Medical Facility at Fort Monroe, Virginia. He died there of stomach cancer on May 20, 1896, never receiving his richly-deserved promotion to Captain. He is interred in Section One of Arlington National Cemetery, alongside his beloved wife, who traveled the West with him for years.

Born at Woodstock, Virginia, in 1853, he was from a military family. He was appointed to West Point in 1873, graduated four years later and was assigned to the 6th Cavalry. From then until the fall of 1885 he was almost constantly on field duty in New Mexico and Arizona. He saw combat in the Victorio campaign of 1879-80 in Mexico, received special commendation from Colonel A. P. Morrow for his efforts. He was a member of Crook’s expedition into Sonora in 1883, which resulted in Chatto’s surrender, serving in (Emmet) Crawford’s command. For this he was mentioned in War Department orders. In 1885 in published General Orders in Arizona, described as having “seen more active duty in the field with Indian scouts than any other officer of his length of service in the Army.” He still had not been promoted beyond First Lieutenant, however.

The son of a Confederate soldier, he stood about 5 feet 11 inches tall, had gray eyes, and a dark complexion. His most prominent feature was his nose, which was quite large. At West Point his fellows had dubbed him Scipio Africanus because his profile was said to resemble that of Roman General Indians were not so classical and referred to him as “Nanton Bse-che,” translated as Big Nose Captain. His wife was was from Frostburg, Maryland, the daughter of T. G. McCullough, a local judge with minor political connections. To he and wife three children were born while they lived in the Southwest. One child died and was buried at Fort Wingate, leaving a son and daughter to grow to maturity. Through all the hardships encountered, the disappointments, even death of a child, his wife never complained. Nor did he. Apparently he personified the motto of West Point, “Duty, Honor, Country.” Even his spare time was spent on the history of artillery, which he hoped would be published. Unpretentious and unassuming, he never sought to glorify himself, doing extraordinary deeds of valor as if they were commonplace.

While he was in East on leave in early 1885, newspaper in his wife’s hometown, the Frostburg Mining Journal, carried a story about him entitled “A Gallant Young Officer”:

“Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood of the 6th Cavalry, is perhaps the most expert scout, trailer, and mountain man of his years on the frontier. Twelve years ago this officer was a young country lad in Virginia mountains. He heard stories told at his father’s hearth of the great (Civil) War, until his heart was full of a nameless longing to see world, and to be a soldier as his ancestors had been. But how should he do this? A good genius guided his steps, and he was gazetted to West Point. He was a boy then, and rather an ungainly one at that, for he had the long figure of his mountain race, not yet filled out to manhood’s growth. After four years of training at our military school you would not have known him. Tall, perfectly straight, with a steely gray eye that looked at you in frank honesty, you felt that he would be a friend upon whom you could lean in time of need as against a rock, or an enemy that would never forget or condone an intentional wrong. Though he has been in the service as a commissioned officer only eight years, he has made a reputation in this brief period of time a man thrice his service might be proud to own. He is the commander of a battalion of five companies of Apache scouts – the hardest service a soldier can have.”

Naturally, an Army officer was needed to accompany the two Indian emissaries, and for this important task Miles turned to the one officer still on active service in the Department best known to Apaches, Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood. With Crook gone, Crawford dead, and Britton Davis a civilian, he was the only man available to Miles who stood a chance of going to the renegade encampment and coming out alive. Miles realized that the hostiles would not meet with an officer unknown to them, and Gatewood had nine years’ service in the region, the last three of them in charge of Fort Apache Agency. He knew and was known to every member of Geronimo’s band, was acquainted with their families and their friends, as well as their enemies, and knew the hardships they had suffered on the reservations. Miles could not send one of the officers he brought with him into the Department, for only one or two had ever glimpsed Geronimo. Even Lawton had never met the Apache chief before. He was summoned to Miles at Albuquerque in the second week of July 1886, and there was issued instructions. Written authority was furnished him to call upon any officer commanding US troops, except those of several small columns then operating in Mexico, for whatever aid might be needed. In verbal instructions to him, Miles particularly cautioned him not to go near the hostiles with fewer than 25 soldiers, for the General feared that the Indians would trap the him and hold him hostage.

Gatewood knew that these orders were impossible to execute. He could never get near Geronimo’s camp with that many troops. Nevertheless, he accepted the task and set out. At Fort Bowie he organized his party, consisting of himself, Martine and Kayitah, George Wratten as interpreter, Frank Huston as packer, and Tex Whaley as a courier. He did not take stipulated 25 soldier escort for, as the latter wrote, “a peace commission would be hampered by a fighting escort in this case, and besides, that number of men deducted from the strength of the garrison at Fort Bowie at that time would spoil the appearance of the battalion at drills and parade.”

With their supplies packed and the men mounted on good riding mules, he set out. Three days later, near the Mexican line at Cloverdale, Arizona, found a detachment consisting of “a company of Infantry, about ten broken-down Cavalry horses, and a six-mule team, and you could have knocked the Commanding Officer down with a feather when I showed my order and demanded my escort.” Actually, he did not want the escort. The commanding officer he mentioned had been one of his instructors at West Point, and he was merely having a little fun, as well as establishing an alibi should Miles ask why he had not taken the escort. The two officers had a pleasant dinner together, after which he left without the 25 soldiers.

Riding southward, he and his little party soon ran short of rations and were reduced to living on ground corn, thickened into a mush with cane molasses. On July 21, they met and joined forces with First Lieutenant James Parker, who was leading a troop made up of 30 cavalryalrymen of the 4th Regiment and 15 infantrymen. Gatewood again failed to ask for his escort, commenting that “a reduction of the escort ordered would have but them (Parker’s command) out of the fight.” When he asked to be put on Geronimo’s trail, Parker replied, “The trail is a myth – I haven’t seen any train since 3 weeks ago when it was washed out by the rains.” “Well,” Gatewood answered, “if that it so I’ll go back and report there is no trail.” Parker knew that such a comment would put him in an unfavorable light. “No,” he said, “if General Miles wants you to be put on a trail, I’ll find one and put you on it. If not we’ll find Lawton who is surely on a trail.”

He was in poor health at the time and probably would have been happy with an excuse to return to Fort Huachuca. Parker ordered his command south toward Bavispe, Gatewood and his party accompanying them. From Bavispe, they continued south to Bacerax, Huachinera, Bacadehuachi, and Nacori, scouting countryside but finding no trace of the hostiles. Finally, on August 3, they arrived at Lawton’s camp on Arros River, some 250 miles south of the border. He again showed Miles’ order, but Lawton was reluctant to allow him to attach himself to the command. Somewhat sullenly he commented that his orders were to track down Geronimo and kill him or force him to surrender unconditionally. He said he intended to do his job but that Gatewood could come along and try to do this. Parker was delighted to be relieved of the peace mission.

While in camp on the Arros River, Lawton received word that the hostiles were 200 miles to north, not far from the border, so he ordered his and Gatewood’s commands to move in that direction. After three days of following the squaw’s trail, Gatewood began to find fresh “sign” an he and his men proceeded more cautiously. A piece of flour sacking was tied to a stick as a flag of truce as they moved forward, for they were in country “fill of likely places for ambush.” The Lieutenant noted that he was quite willing “to give Kateah and Martine a chance to reap glory several hundred yards ahead.” Early the next morning, August 24, he told the two scouts, Martine and Kayitah, to go ahead alone, to try to locate Geronimo, and have a conference with him if possible. After they had located the camp, Kayitah’s cousin, with permission from Geronimo, jumped atop a rock and called to ask why the 2 were approaching. They replied that they were messengers for Miles and Gatewood and wish to talk peace with Geronimo. At sunrise on August 25, he and his small party started up the mountains, still holding aloft their white flag of truce. Within a mile of Geronimo’s camp, they were met by an unarmed Chiricahua warrior sent to deliver the same message brought by Martin, i.e., that Geronimo wished to meet to discuss the terms of surrender. While he was speaking with him, three armed hostiles appeared with a further communication, this one from Natchez. It was suggested that the meeting be held at a nearby bend in the Bavispe River where wood, water, grass and shade were available.

To all of this Gatewood agreed, giving orders for most of his party to turn back and writing instructions for Lawton, while the Indians exchanged signals, consisting of “smoke and shot,” with their comrades waiting at the mountain camp. As he turned to the designated site of meeting, his party was reduced to himself, Martine, Wratten, and two soldiers, Martin Koch and George Buehler. Arriving at the bend in the river, he halted his men outside the meeting space and told them to wait. Riding on it, he unsaddled and threw his saddle over a log, all his arms attached to it. Thus he stood alone and unarmed, when within ten minutes the hostiles began drifting in quietly and likewise unsaddling. Among the last to arrive was Geronimo. He laid his Winchester down about 20 feet away and came up to shake Gatewood’s hand, remarking on his thinness and inquiring about his health. Then signaled rest of Gatewood’s party to ride in and unsaddle, which they did.

As he later described the event, he paused to inquire: “Gentle reader, turn back, take another look at his (Geronimo’s) face, imagine him looking me square in the eyes, and watching my every movement, 24 bucks sitting around fully armed, my small party scattered in their various duties incident to a peace commissioner’s camp; and say if you blame me for feeling chilly twitching movements.” Geronimo then announced that his party was ready to hear General Miles’ message. Gatewood said it briefly: “Surrender, and you will be sent to join the rest of your people in Florida, there to await the decision of the President as to your final disposition. Accept these terms or fight it out to the bitter end.” When the import of Miles’ message became clear to the Apaches, there was “a silence of several weeks,” as Gatewood described it. Actually it lasted only a moment or two, after which Geronimo passed a hand across his eyes and extended his arms forward. Both hands trembled badly, and he asked again if Gatewood had something to drink. “We have been on a three-days drunk,” he said, “on the mescal the Mexicans sent us by the squaws who went to Fronteras. Mexicans expected us to play their usual trick of getting us drunk and killing us, but we have had the fun and now I feel a little shaky. You need not fear giving me a drink of whiskey, for our spree passed off without a single fight as you can seen by looking at the men sitting in this circle.”

It was obvious to Gatewood that despite his drinking, Geronimo was remarkably well informed about activities of both Mexican and American pursuers. Since there was nothing to drink, Geronimo said that they should continue on with their business. He stated that he and his followers would leave the warpath only on condition that they be allowed to return to the Arizona reservation, occupy the farms they had held when they left, and furnished with usual rations and farming implements with guaranteed exemption from punishment for what they had done since leaving. By the latter, meant no civil trial by civilians. If Gatewood was authorized to accede to those terms, he concluded, the war would be over. “I explained that the Big Chief, General Miles, whom they had never met, had ordered me to say just so much and no more, and that they knew it would make matters worse if I exceeded instructions,” Gatewood later wrote. He continued that this would be the renegades’ last chance to surrender, for if the war continued they would all be either hunted to the death, or, if they surrendered thereafter or were captured, the terms would not be so liberal. Both Geronimo and he were speaking in emphatic terms, each stating his absolute wishes, not what he could accept as a compromise. Geronimo suddenly shifted the course of the conversations as darkness fell. What kind of man was Miles, he wanted to know. He said he knew Crook well and might surrender to him, but knew nothing of Miles. He asked Miles’ age, size, color of eyes and hair, and whether his voice was harsh or agreeable to the ear. Did he talk much or little, and did he mean more or less what he said? Does he look you in the eyes or down at the ground when he talks? Has he many friends among his people and do they generally believe what he says? Do the soldiers and officers like him? Had he had experience with other Indians? Is he cruel or kind-hearted? Would he keep his promises? Gatewood answered each of these questions truthfully to the best of his knowledge, pleading ignorance on some points. The Indians listened intently to each of his answers. Then Geronimo said, “He must be a good man since the Great Father sent him from Washington, DC, and he sent you all this distance to us.”

Apparently he had made up his mind, but gave no indication of what it was. Just before departing, Geronimo had a final question for the Lieutenant. “We want your advise. Consider yourself one of us and not a white man. Remember all that has been said today, and as an Apache, what would you advise us to do under the circumstances?” He did not hesitate. To have done so would have been fatal to his mission. “I would trust Miles and take him at his word,” he replied. As his reply was translated, hostiles looked very solemn. Everyone knew him, and they trusted him as man who had never knowingly lied to them. Finally Geronimo broke the silence to sat that the next morning he would let him know what they had decided. Each of the parties returned to their camps to rest. The rest was interrupted early the next morning, August 26, by the cries of scouts on picket. Hostiles were approaching and asking for the Lieutenant. He went out to meet them. When the hostiles saw him approaching, they dismounted, unsaddled their horses, and put their weapons across their saddles – all except Geronimo, who kept a large pistol under his coat beside his left hip. He and the Apaches seated themselves under an ancient mesquite tree and again held a conference, while the US camp waited silently. They made no overt moves, knowing that such would only precipitate a crisis.

First the Apaches wanted him to repeat his entire description of Miles, which he did. In the process, renegades apparently were satisfied with his answers, for immediately afterward Geronimo stated that he, his warriors, and his squaws and children were willing to meet the General at some point in the US to talk and to surrender to him in person, provided that he and the US soldiers would accompany them to border to protect them from Mexicans and other Americans they might encounter. To all this he agreed, then led Geronimo into US camp to introduce him to Lawton and Leonard Wood, who had never met the Apache chief. Lawton likewise approved the agreement just reached, whereupon all the hostiles entered the US camp. All, soldiers and Indians, visibly relaxed. The Apache wars were over, provided Miles honored his promise to meet Geronimo. In a letter to his wife, Gatewood described the events of the day. That he was not lying to his wife, trying to assume more importance in the surrender and thus gain stature in her eyes, is corroborated by statements of George Wratten, who served as interpreter for much of the peace talks. Wratten later wrote, “Would you believe me? Old Geronimo told Gatewood, ‘I am your friend, and I’ll go with you anywhere.’ He always had great faith in Gatewood, for he had never deceived him. He was the only man who could safely have gotten within gunshot of the old savage, and Miles knew that when he sent him out.”

But before Gatewood could again embrace his wife, and before Nachez and the Apaches could see their families, they all had to get safely out of Mexico, and Miles had to meet with them to formalize the surrender. These two steps did not prove simple. On the same day the train left Bowie Station carrying Geronimo and the Apache renegades eastward to San Antonio, and eventually to Florida, Nelson A. Miles, issued Field Order Number 90. Paragraph 7 stated, “First Lieutenant C. B. Gatewood, 6th Cavalry, having reported at these HQ upon the completion of the duty to which he was assigned in connection with the Chirichua and Warm Springs Indians, will rejoin his station at Fort Stanton, New Mexico, via Albuquerque, New Mexico,” Ironically, that statement was followed by the standard entry, “The travel as directed is necessary for the public service.” Gatewood’s transfer to his duty station at Fort Stanton was intended to removed him from the public spotlight, for no sooner had Geronimo departed Arizona than the fight began to secure whatever glory – and promotion might be had therefrom.

Gatewood was not safely hidden at Fort Stanton. Too many people knew of his part in the recent campaign, and newspapermen might reach him there. Miles therefore changed his mind about sending him back to his reg. On October 10, he was named aide-de-camp to Miles, which meant that he was always close enough for General to keep him under close surveillance. The only positive recognition which Miles extended to him for his exploit came in form of an invitation to accompany delegation of Arizona Indians to Washington, DC. Captain John A. Dapray was instructed by Miles to tender this invitation to Gatewood. “I shall never forget the expression on his face when I made known to him that General Miles’ wish in that respect,” Dapray later recalled. “He looked positively alarmed, saying, ‘These clothes on my back (pointing to his blue flannel shirt, which he was wearing without a blouse) are all the clothes I have with me. I can’t go to Washington, DC very well and I hope the General will let me off.’ Depray explained that the invitation was meant as “a bit of rest,” whereupon Gatewood replied, “Well, tell the General if it is that only, I will appreciate it more if he will let me go into the Post for a few days to see my wife and child.”

Even as Miles’ aide-de-camp, he kept receiving letters from Army friends and from civilians in region congratulating him on his splendid and courageous achievement in securing Geronimo’s surrender. Miles grew so jealous that be began enacting a petty revenge. Gatewood’s wife later detailed one such incident: “A fete was given in Tucson, guest of honor being Lieutenant Gatewood. In the arrangements, so much was said of him that General Miles got enraged at playing second fiddle, and at the last minute, after we had accepted invitations of all sorts and had clothes made for the occasion, he ordered Gatewood to stay behind and look after office during his absence – a clerk’s work and unnecessary. Some papers came to office to be signed, certifying that servants in Miles household were ‘packers,’ receiving packers wages from the government. Gatewood refused to sign the papers, for which Miles did not forgive him, and sought on several occasions to court martial him, but failed to find a reason which would not show up some of his own practices. It was common gossip at HQ that Amos Kimball (the servant indicated above) had made much money at government expense with Miles’ connivance, notably on a contract for stores for the army, and that Miles had an old man of the mountain (a black mailer) on his back and had to take him everywhere he went. Such a storm of comment and inquiry met him when Lieutenant Gatewood – the man for whom Tucson fete was arranged – did not appear that he found himself cornered, and made the mistake of publishing in a San Francisco paper that he “was sick of this adulation of Gatewood, who only did his duty.” No soldier ever received a higher compliment, and once more Miles was made to feel that he had made a slip. Wishing a transfer from Miles’ direct command, a transfer from his own regiment, he applied in December 1886 for a position in Quartermaster or Commissary Department. Miles agreed to request, sending it forward with his endorsement and recommendation. In fact, he came close in this endorsement to giving him some measure of credit for his exploit in the Geronimo campaign: “His zeal and courage,” wrote Miles, “are of the highest order, and recently in the campaign against Geronimo he bore a very conspicuous part, especially at the close, when his good judgment and heroism aided much in bringing about satisfactory results.” 2 years later, in 1888, again applied for a transfer to Commissary Department, as well as promotion to Captain. This time he sought political endorsement and secured it from the Lieutenant Governor of California and a state senator and two National Democratic Committeemen from the same state. The influence of these men was too slight to help, however, and he continued as Miles’ aide-de-camp.

Finally on September 14, 1890, was allowed to rejoin his regiment, Geronimo campaign now forgotten by public. From Fort Wingate, New Mexico, the regiment was transferred to the Dakotas to participate in the Sioux War (the ghost dance episode). He was in the field against Sioux from December 1890 to Jan 1891, when his health broke and he took sick leave for a year. He still had not been prom beyond First Lieutenant or had any recognition for his earlier services, despite his wife’s use of family connections. She had written Senator A. P. German of Maryland, a friend of her father, who responded: “I fear that I cannot have any great influence with the powers that be, but will take pleasure in doing what I can. I think he deserves it.”

In the fall of 1891, his health recovered enough to permit him to return to duty with his regiment, which was then stationed at Fort McKinney, Wyoming. There he and regiment were involved in a smoldering feud that came to be known as the Johnson County War. Wyoming was then undergoing struggle between big ranchers and farmers. The two parties confronted each other on morning of April 10, 1892. Early on the morning of April 13, just as the farmers were preparing to storm the buildings in which ranchers where hidden, and to kill them, a detachment of the 6th Cavalry arrived in response to a call for Federal assistance from Acting Governor Amos W. Barber.

Colonel J. J. Van Horn, in charge of the troops, induced the cattlemen to surrender, and they were taken to Fort McKinney for detention. The Post Stockade was not large enough to hold all of the cattlemen and the overflow was locked in the band barracks, which was vacated for that purpose. A few nights later, a guard saw two men running away from band barracks and sounded the alarm. Investigation revealed a huge bomb hidden under the barracks. It was made from hot-water boiler filled with gun powder and rifle bullets, and a firing mechanism made from an old gun. About 200 yards of wire led from it to the nearby stables. When those who planted the bomb – and it was widely assumed deed has been done by the farmers – tried to explode it, the wire had broken. The guard was doubled around barracks until Easter Sunday morning, April 17, when the prisoners were moved out on their way to Cheyenne and a civil trial. The troops then relaxed, only to be awakened on morning of May 18 by cries of “fire.” Later three cowboys of the Red Sash Ranch crew would be arrested for the crime. Their motive was that the troops were hindering the cattlemen’s efforts to wipe out the farmers. The cowboys had thrown kerosene on the Post Trader’s store and set it on fire, hoping that the high wind would blow the flames onto four connecting wooden barracks. The water system at the post proved inadequate, and the troops formed a bucket brigade. Still the fire grew. Gatewood, the post ordnance officer, was called to blow up the second barracks and save the final two from destruction. As one side of the second barracks ignited, he and two helpers entered it to lay two 60-pound bags of rifle powder inside, placing iron bunks atop them to increase the explosive force. There was no fuse. The fire would ignite the powder. Just as Gatewood, the last man out, was leaving the barracks the powder exploded, and one of the iron bunks hit his upraised left arm, smashing it. He was badly burned also. The arm never healed properly, and he took sick leave November 19, 1892, retiring to Maryland to live.

Then in 1896 he began having severe stomach pains and went to Fort Monroe for treatment. There he died at 11:45 pm, May 20, 1896, of stomach cancer. At the time, was awaiting medical retirement and promotion for he was senior Lieutenant in 6th Cavalry and 8th ranking Lieutenant in the entire Army. The day after his death his body was moved by steamer to Washington, DC. From there it went by caisson to Arlington National Cemetery for interment with full military honors.

On May 23, 1896, Colonel D. S. Gordon, commanding 6th Cavalry, issued GO 19, which stated: “It is with extreme sorrow and regret that the Colonel commanding the regiment announced death of First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood at Fort Monroe May 20. Too much cannot be said in honor of this brave officer and it is lamentable that he should have died with only the rank of a Lieutenant, after his brilliant services to the Government. That no material advantages reverted to him is regretted by every officer of his regiment, who extend to his bereaved family their most profound, earnest and since sympathy. As a mark of respect to his memory, the officers of the regiment will wear the usual badge of mourning for the period of 30 days.”

Years later, his son, Charles B. Gatewood, Jr., would state the same sentiment, but with brevity and bitterness: “His reward, for services that have often been described as unusual, was like that of many another soldier who has given his all that his country might grow and prosper. For himself a free plot of ground in Arlington National Cemetery, and to his widow, a tawdry 17 dollars a month.”

A belated movement to get him the Medal of Honor as recognition for his services in the Geronimo campaign, made in 1895 when it was widely assumed his health was such that he would not live, was denied on the basis that he had never come under actual fire. Curiously, the Commanding General of the army, Nelson A. Miles, had endorsed the recommendation which was submitted by Captain A. P. Blocksom of 6th Cavalry. Miles signed it, even though it carried the statement, “for gallantry in going alone at the risk of his life into the hostile Apache camp of Geronimo in Sonora…” This was contrary to what Miles was then writing in his “Personal Recollections,” published in 1897. Gatewood would certainly have been justified in feeling bitter when he saw others whose contributions were smaller, receiving promotion and medals. His son later commented: “My father was deeply and terribly hurt, more in his sense of the fitness of things than in any sense of his own injury. If my father had decided to fight the issue, be would eventually have forced all the honorable opposition into his camp, leaving the culpable ones in a position where they might easily have been exposed and disgraced, but he did not. It would have caused a scandal and worked injury to the army, and knowing my father as I did, I feel sure that this consideration rather than his own hurt pride or fear of the opposition kept him silent.”

There was considerable controversy in the years that followed over who should get credit for securing Geronimo’s final surrender. As indicated by Gatewood’s son, he never took a personal part in such arguments. Charles D. Rhodes, who graduated from West Point in 1899 and joined the 6th Cavalry, later wrote of his intimate association with Gatewood: “Nothing could drag out of this modest, unassuming and even diffident officer, anything which might glorify in the least his part in the ending of the interminable Apache raids. My regiment was a unit in feeling that credit for Geronimo’s surrender belonged to him, and there was considerable quiet criticism that no sentimental recognition was accorded him for the outstanding act of courage and good judgment, which only field soldiers could truly appreciate.”

One aspect of Gatewood legend that grew among his comrades and admirers was his “lack of fear.” Despite his own comments to the contrary, showing his healthy respect of Apache strength and occasional fears for his own safety, others wrote that he was “never afraid.” J. A. Cole, in 1886 a Second Lieutenant with the 6th Cavalry, later stated: “Genial, careless, devil-may-care, not in a reckless way, but just naturally so, he was the man with the steel spine when that kind was needed.” However, one point almost all who knew Gatewood was unanimous, he was modest. Cole stated, “…he was modest to and past a fault.” The meek may inherit the earth, but they rarely get credit during their lives for what positive good they do.

Section 1, Grave 804, Arlington National Cemetery.

His wife, Georgia McCullough Gatewood, is buried with him. She was born on October 6, 1854 and died on November 13, 1946, outliving him by 49 years. His son, Charles Bhaer Gatewood, Colonel, United States Army, is also buried in this gravesite.

LT 6 US CAV APACHE IND CAMPAIGN

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/20/1896

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SITE 804

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

GATEWOOD, GEORGIA WID OF GATEWOOD, CHARLES BARE

- DATE OF BIRTH: 10/06/1854

- DATE OF DEATH: 11/13/1946

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 02/04/1947

- BURIED AT: SECTION 1 SITE 804

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

- WIFE OF CHARLES BARE GATEWOOD -LT 6TH US CAVLARY US ARMY

GATEWOOD, CHARLES BHAER

COL U S A

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF BIRTH: 01/04/1883

- DATE OF DEATH: 11/13/1953

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 12/03/1953

- BURIED AT: SECTION 1 SITE 804-A

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard