The Department of Defense announced today the death of two Marines who were supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

- Corporal Binh N. Le, 20, of Alexandria, Virginia

- Corporal Matthew A. Wyatt, 21, of Millstadt, Illinois

Both Marines died December 3, 2004, from injuries received as result of enemy action in Al Anbar Province, Iraq. They were assigned to 5th Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

News media with questions about these Marines can contact the 2nd Marine Division Public Affairs Office at (910) 451-9033.

WASHINGTON — A Marine corporal from Fairfax County was killed in Iraq last Friday.

Binh N. Le

Binh Le, 21, was manning a checkpoint when a car bomb exploded.

Le was born in South Vietnam. He came to the United States when he was 6 years old and grew up with an adopted family. However, he still kept in contact with his parents in Vietnam.

“We’re very proud. He served the country. He’s a first-generation here. I know he loved his job and he would do what he wanted to do. So our family is very proud of him,” Le’s adopted father, Luong La, said.

Le’s relatives here say they’re trying to make sure his biological parents can come to Arlington National Cemetery for his funeral.

Sadly Fulfilling Marine’s Dream

Funeral to Bring Parents to U.S.

Binh N. Le had not been back to the land of his birth since he came to the United States with an aunt and uncle at age 4, leaving his parents behind.

So, after he graduated from Edison High School in Fairfax County in 2002 and before he joined the Marine Corps later that year, Le made a joyous pilgrimage to Vietnam to visit his mother and father. Recently, he told one of his aunts in the United States that when he returned from his second tour in Iraq in April, they would make the trip together.

But Le, a 20-year-old Corporal from Alexandria, Virginia, was killed last week in Iraq. The Pentagon said he died of injuries suffered in enemy action in Anbar province; the Associated Press said a car bomb killed him and a fellow Marine, Corporal Matthew A. Wyatt, 21, of Millstadt, Illinois, as they patrolled near the Jordanian border.

Now, instead of awaiting his return visit, Le’s parents will be making their way to this country to attend his funeral when it is scheduled at Arlington National Cemetery.

Le was assigned to the 5th Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division of the 2nd Marine Expeditionary Force. He was trained as a field artillery cannoneer and belonged to the unit’s Sierra battery. He was proud to be a Marine, said an uncle, Luong La of Dale City, Virginia.

La said the military was a natural choice for his nephew, a member of his high school’s Junior ROTC program. His father had served in the Vietnamese army, and Le had “that kind of blood.”

Le was proud, too, of his adopted country, his uncle said. He became a U.S. citizen while serving his first tour in Iraq, and he hoped to sponsor his parents to join him in this country. “That was his dream,” La said.

In the meantime, he wanted to make a career of the Marine Corps. When Le told relatives that he would be returning to Iraq, La remembers saying he was a “little bit scared for him.” But Le responded that he had a duty.

“He said if he don’t do it, no one do it. He do whatever his job,” La said. “That was his attitude in being a Marine.”

Le was small and slender, quick and energetic, recalled Lynn Hall, his pastor at Lorton’s Gunston Bible Church. Le and Hall’s son Joe had been close friends since Le joined the church as a boy, Hall said. He said Le was the kind of kid who never stopped moving and always liked to be at the center of things, the kind who would declare that he planned to throw a birthday party — for himself.

When he visited on leave, Le sometimes stayed at Hall’s house. The pastor fondly recalled waking up in the morning to find the young man asleep on the sofa after staying out until 3 a.m. to cram in visits with friends.

Hall said Le told him he joined the Marine Corps because it was the “best fighting force in the world.”

“I would sometimes use the term ‘soldier’ with him, and he hated to be called ‘soldier’ because he was a Marine, not a soldier,” Hall said.

Le told church members that he helped secure a bridge south of Baghdad during the initial invasion of the country in 2003 and was greeted kindly by the people there. “He said the Iraqi people were so glad they were there it just about put him in tears,” Hall recalled.

Le was known as a talented musician. He played drums, and in junior high school he formed a band with a cousin and Joe Hall. After the band broke up, he picked up keyboards and played both instruments for the church, Lynn Hall said.

“He was an excellent drummer, but his music teachers would always get mad at him ’cause he’d play them loud,” he said. “He’d really bang them.”

Le called home often to speak with his American family — Thanh Le and Hau Luu, the aunt and uncle who brought him to this country and legally adopted him, and La and his wife, Tuc-cuc Thi Tran, with whom he often stayed while on leave.

In one recent conversation, he told La that he was tiring of military food and wanted to try to make Vietnamese-style meatballs. La promised to ship the seasonings overseas soon.

The last time they spoke, just two weeks ago, La said he advised his nephew to “keep his head down.”

“Yeah,” the young man responded. “We’ll do that.”

For an Immigrant Marine, Burial Close to Home

Virginia Vietnamese Family Mourns at Arlington

In life, Binh N. Le adopted this country as his own. In death, his country returned the honor.

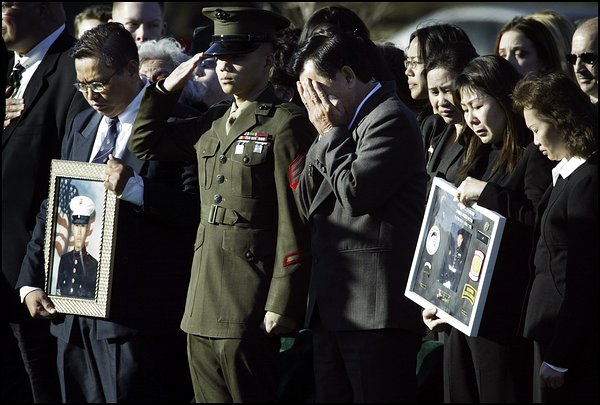

Le, 20, a Marine corporal who was born in Vietnam, grew up in Fairfax County and died in Iraq, was buried yesterday under an unseasonably warm sun at Arlington National Cemetery. Over his coffin stood two Marines in dress uniform, one holding a U.S. flag steady in the breeze, the other the flag of the fallen South Vietnam.

Luong La, left, holds a portrait of his nephew, Binh H. Le, at Arlington. With him are Marine Sgt. Suong Nguyen, an interpreter; Le’s parents, Lien Van Tran and Kim Hoan Phi Nguyen; and an aunt, Tuc-cuc Thi Tran.

Le was killed December 3, 2004, in Al Anbar province — by a car bomb set off near a checkpoint he was manning, his family was told. Corporal Matthew A. Wyatt, 21, of Millstadt, Illinois, also died in the attack. Le, a member of the 5th Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, was serving his second tour in Iraq and was scheduled to come home in April.

As a boy in Vietnam, Le was adopted by Hau Luu and Thanh Le, an aunt and uncle who soon immigrated to America. He was raised in the Alexandria section of Fairfax by the couple and another aunt and uncle, Tuc-cuc Thi Tran and Luong La of Dale City.

He visited his birth parents just once, a pilgrimage made after he graduated from Fairfax’s Edison High School in 2002. U.S. officials intervened to ensure that they could come to the funeral, helping them secure visas and passports.

A Marine Staff Sergeant handed one folded U.S. flag to Le’s father, Lien Van Tran. With La translating, Tran, who once served in the South Vietnamese army, told National Public Radio recently that he had not wanted his son to join the Marines but was proud of his service.

“He did the right job for the family, for the country, for himself,” Tran said.

La received a second U.S. flag. Nearby stood Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz and Representative James P. Moran Jr. (D-Virginia).

Friends said Le embraced the life of an American teenager long before joining the Marine Corps in 2000. He surrounded himself with devoted friends, many of whom he met through Junior ROTC or Lorton’s Gunston Bible Church.

They described him as energetic and engaging. In high school and afterward, he played in a series of bands with young members of his church. One, a Christian group called Eyeris, built a small, loyal following at churches and coffeehouses. Drums were his passion, but he also had a talent for the keyboards and trumpet, friends said.

“He played everything by ear,” said Jamey Payne, a member of Eyeris. “As long as he knew what it took to make a note come out of it, he could play it.”

A Web site set up by his friend Paul Stadig features testimonials from dozens of people. Le had so many friends, Stadig said, that many of them didn’t know each other. “All of his friends saw him as one of their best friends,” he said. Next summer, Le was to have served as a groomsman at Stadig’s wedding.

Le was a groomsman at Payne’s wedding in May 2003, arriving to the surprised delight of the bride and groom, who thought he was still on his way home from Iraq.

Le returned from his first tour brimming with stories of the gratitude of ordinary Iraqis, friends said. Stadig recalled Le describing an Iraqi family that invited the Marines for tea. When they were finished, the Marines handed their cups back, only to find them quickly refilled. Many cups later, they learned that according to local custom, if a guest drains his cup all the way, it should always be refilled.

Payne said Le saw the conflict in Iraq through the prism of his own life story.

“He understood what it was like in a fairly oppressed society, and he really enjoyed the freedoms he had over here,” Payne said. “He wanted to help others experience that. . . . It was a true American story.”

Grieving Mother Holds One Last Wish for Son

Vietnamese Parents Seek U.S. Residency After Marine’s Death

A weeping Kim-Hoan Thi Nguyen kissed her 7-year-old son goodbye at the Ho Chi Minh airport and told him it would be a long time before they would be together again. Little Binh Le boarded the plane and flew off to the States, where his mother hoped he would flourish. It was 1991.

She next saw Le when he visited Vietnam at 12. He cooked her french fries.

Kim-Hoan Thi Nguyen visits her son’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery. She wants to be able to visit regularly,

but a bill for her permanent residency is stuck in committee.

He visited again when he was 18 and a recent graduate of Edison High School in Fairfax County. They had a party.

Their next reunion came in December 2004. At his funeral, at Arlington National Cemetery.

Le, a Marine corporal and a Vietnamese citizen, was killed at age 20 while defending his desert base in Iraq. The month after his death, he was awarded U.S. citizenship in a ceremony at which speakers lauded his valor.

Nguyen, who has lived with a friend in Springfield since the funeral, wants to stay. Wracked with guilt that she sent her only child off to a life that was cut short, she wants only to lay flowers on his grave each Sunday. Yet, although parents of immigrants killed in combat are eligible for permanent residency, Nguyen’s applications have been denied.

The reason: She and Le’s father gave up their son for adoption to an aunt and uncle so he could emigrate with them.

“I lost my son for many years, and I do not want to lose him again,” Nguyen, 48, said yesterday through an interpreter. She said her visitor’s visa will expire in December.

Nguyen said the adoption consisted of a handwritten piece of paper — signed by the two couples and a neighbor acting as a witness. Lawyers who have helped her and Lien Van Tran, Le’s father, apply for permanent residency say the adoption was never official, a conclusion supported after an investigation by a lawyer in Vietnam.

But to U.S. immigration authorities, Le benefited from the adoption — legal or not — by coming to the United States as the son of his aunt and uncle. Le’s birth parents, therefore, cannot benefit from their relationship to him, according to a denial Nguyen received from the Board of Immigration Appeals.

Relatives said Le dreamed of becoming a U.S. citizen and helping his parents, who later divorced, gain citizenship. Le was raised by his adoptive parents, Hau Luu and Thanh Le of Alexandria, and another aunt and uncle in Woodbridge. “That was probably one of the things that he wanted most, was for them to come over and live with him,” said cousin David La, 15. “That was his dream.”

U.S. Rep. James P. Moran Jr. (D-Va.) found their case so compelling that he filed a private bill in Congress last February that would grant permanent residency to Nguyen, Tran, their new spouses and Tran’s daughter. But it has been stuck in committee since March.

“Corporal Le served our country with distinction, paying the ultimate sacrifice for his bravery. It seemed like a fitting tribute to try and help his biological parents become part of the nation he so dearly loved,” Moran said yesterday in a statement. He said he is still pushing the bill, but added: “Any bill that has even a whiff of an immigration-related provision faces a very tough road here in the House.”

Le was raised in the Alexandria area of Fairfax. He grew up a typical American teenager, active in his church and a member of the Junior ROTC.

On December 3, 2004, Le was killed when a water truck carrying 500 pounds of explosives bore down on Camp Terbil. Le and Marine Corporal Matthew A. Wyatt, 21, of Millstadt, Ill., fired at the driver, killing him, before the truck crashed and exploded, killing Le and Wyatt and wounding six other Marines.

That Le died defending his fellow Marines is no surprise, said Paul Stadig, a friend. Le was very loyal, he said.

“He was just always the military type,” Stadig said. “He always loved the idea of the few and the proud and being the best that he could be.”

Nguyen cherishes the memories she has of her son as a youngster. Once, she recalled with a wistful smile, a tiny Le tried to quiet children playing in the street because his mother was napping. But despite their love for Le, Nguyen said, she and Tran felt certain that his future was more promising in the United States.

“I wished I am going to see my son again, but for how long, I don’t know,” Nguyen said, recalling how she felt when she said goodbye to Le. “I felt very, very bad for leaving my son, but because of his future, his life, still I had to. . . . I was sick for a couple months.”

Nguyen said she tried hard to stay connected to Le’s life by asking lots of questions in regular phone conversations. On his first visit to Vietnam, she brimmed with joy. “He looked like a good boy,” she said.

Le did not tell Nguyen he was joining the Marines. It was only after he was on his first tour in Iraq — during the invasion in 2003 — that she learned from the aunt and uncle of his enlistment. Finally, he called her from his post.

“I told my son, ‘You have to take care of yourself. I want to see you again,’ ” Nguyen said. When she learned of his death, Nguyen tried to kill herself, she said. Her sisters and mother stopped her.

After pushing for Le’s posthumous citizenship, the Marine Corps took on his parents’ cases, helping them file applications for permanent residency. When the applications were denied, the Marine Corps found immigration lawyers who agreed to represent them for free.

“It was important to the very senior people in the Marine Corps leadership to make sure that we were keeping faith with this Marine’s family,” said Christopher Rydelek, head of legal assistance for the judge advocate of the Marine Corps.

After his options were exhausted, Tran returned to Vietnam on Jan. 30, said Lynda Zengerle, an immigration lawyer in the District who helped with his petitions.

“He was clearly crushed,” Zengerle said. “I think he was hopeful that he could come back to visit his son’s grave at least once a year.”

Nguyen said a lawyer with a District law firm helped her petition the appeals board in Falls Church, which is part of the Justice Department. When the request was denied, she said, he told her there was no hope.

“For the law, I agree with that, because I gave up my son for his adoptive parents,” Nguyen said. “But I feel bad, because my son died.”

Nguyen said she also fears that her son’s death in the name of the United States — and the attention it received here and in Vietnam — could bring persecution by the communist government in Vietnam.

In the United States, Nguyen has no family and few friends. It would be hard to start a new life but worth it to be near Le, she said. If she is allowed to stay, Nguyen said she might like to be a babysitter, because she adores children. Whether her husband in Vietnam will join her is another matter, she said.

“American people live by plans,” she said. “Vietnamese people live by hope.”

- LE, BINH

- CPL US MARINE CORPS

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 10/06/2004 – 12/03/2004

- DATE OF BIRTH: 10/06/1984

- DATE OF DEATH: 12/03/2004

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 12/22/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8088

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Posthumous Citizenship Granted to Marine

ARLINGTON, Virginia – He was born in Vietnam and came to America at age 6. After growing up in northern Virginia, he joined the Marines even though he was not a U.S. citizen.

Corporal Binh Le became an American on Thursday, but he could not attend the citizenship ceremony held in the shadow of the Pentagon. Last month, he was buried nearby in Arlington National Cemetery, the victim of a truck bomb in Iraq during a voluntary second tour of duty there.

Le, 20, grabbed his rifle when the truck packed with explosives attacked his military post December 3, 2004. He had run to a position to fire on the driver and hold back the vehicle when it exploded. His commanding officer recommended him for a Silver Star.

“His final act of bravery saved the lives of others,” Captain Christopher J. Curtain wrote in a letter read at the ceremony. “I will be forever grateful for his heroism.”

An estimated 37,000 citizens of other countries serve in the U.S. armed forces. Since the Iraq war began, 54 have been awarded posthumous citizenship.

Le was raised by his aunt and uncle in Alexandria, Virginia. His parents, Lien Van Tran and Kim Hoan Thi Nguyen, traveled from Vietnam for his funeral. They are divorced but would like to remain in the United States to be close to their son’s grave, Nguyen said.

“There’s no way to describe the pain,” she said.

Rep. James P. Moran, D-Va., said he is working to offer citizenship to Le’s parents, which could require congressional action.

“I think this is a compelling enough case that we can get a single bill for citizenship for his parents,” Moran said. “They certainly deserve it.”

Tran said they didn’t have a problem with their son enlisting in the Marine Corps, but they wanted him to have time to attend college.

“His main concern was to join the military so that he could help protect the country he loved so much,” Tran said.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard