Contemporary News Account: October 24, 1997

A 4-inch bone fragment has settled the case of Air Force Major Bobby Gene Huggins. His family and country can now say goodbye.

More than 27 years after his jet went down in a South Vietnamese jungle, DNA tests of the fragment found at the crash site have confirmed the Texas-based pilot was a casualty of war.

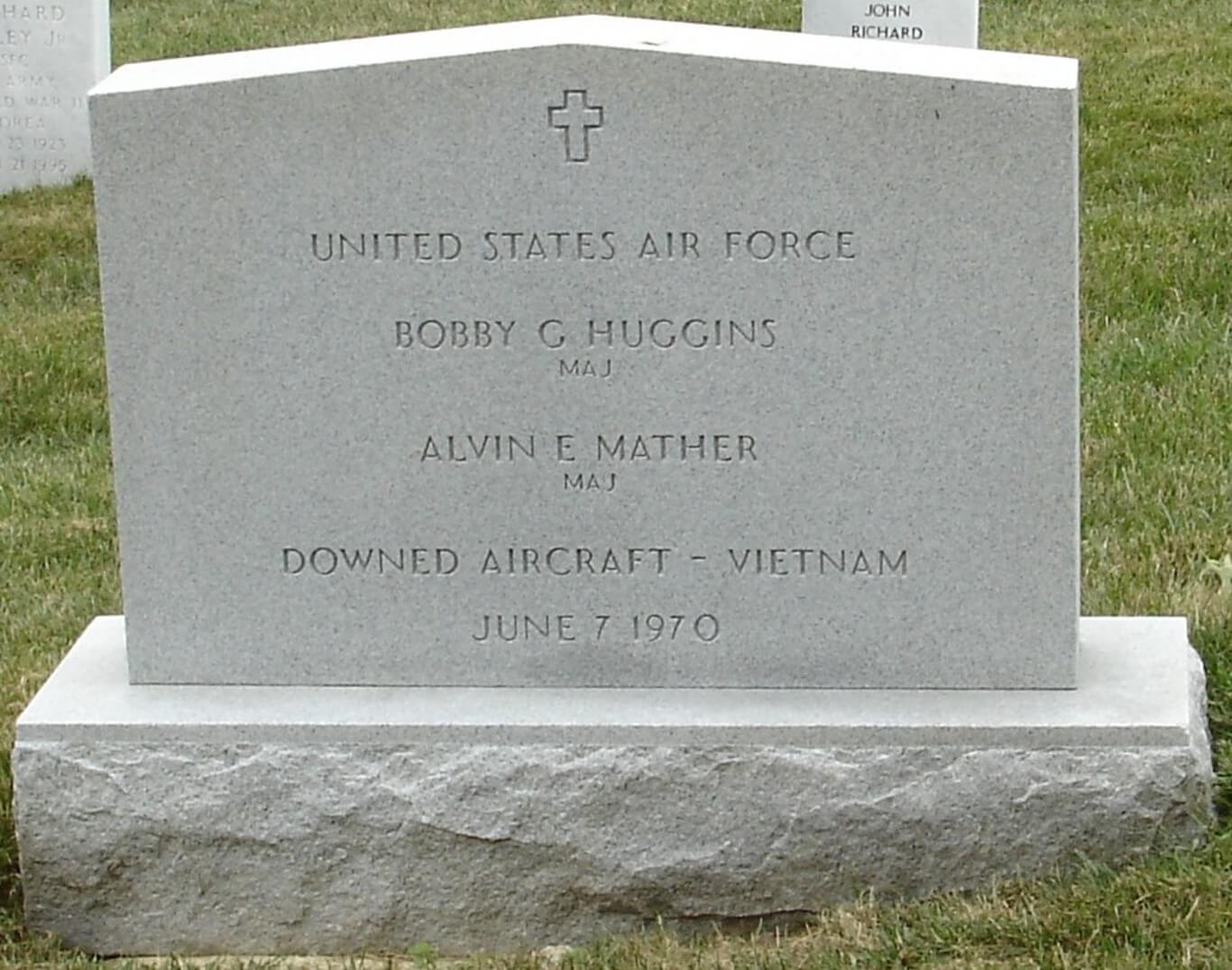

No longer among the more than 2,100 Americans unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, he will be honored Friday with a band, color guard and firing party at Arlington National Cemetery. A coffin will bear the remains, a 4-inch piece of his right forearm.

“He was a hero and he deserves it,” said Debbie McIntosh, Major Huggins’ oldest daughter, who will gather with family and friends for a ceremony ending her decade-long mission to bring her father home.

“For me, not being able to bury him was something that was not quite finished. It needs to be finished,” said the Collin County resident. “Maybe this will help the loss heal. I hope so.”

Ms. McIntosh was 13 years old when her father said goodbye to his wife and four children at Dallas Love Field and flew off to his first combat. Three months later, she was old enough to fear the big black car outside her home in Anna and to understand a chaplain’s stunning words.

Military reports say an RF-4C Phantom carrying Major Huggins and his navigator, Major Alvin Mather, crashed June 4, 1970, while on a night photo-reconnaissance mission near the Cambodian border. A rescue team’s limited search of the jet’s wreckage the next day recovered a hand, which was used to identify Mr. Mather. Three days later, Major Huggins, age 35, was declared “killed in action, body not recovered.”

That’s what the chaplain told the pilot’s wife, Shirley, in 1970. But a document found in his military file in 1985 indicated the family had been misled, his daughter said. An Air Force mortuary officer “requested that we not reveal the fact any remains have been recovered in this case,” according to a June 1970 memo. “He did not think it appropriate in this case, since no identification has been made.”

Ms. McIntosh, still a resident of Anna, said she became curious, not angry. Never doubting her father’s death, she and his sister began searching for proof of it. “I don’t think it was vicious. It was just stupid. They were trying to go easy on the family,” she said. “But I wondered what else did they not tell us.”

Ms. McIntosh, 40, began communicating with military officials and working with the National League of POW/MIA Families, a private group pressing the U.S. government for an accounting of the 2,109 Americans (including 17 from the Dallas area) missing in Southeast Asia. She began to get answers in 1992 with an investigation of her father’s probable crash site by members of the U.S. Joint Task Force for Full Accounting.

Established that year to direct the government’s search for American MIA’s, the task force seeks identifiable remains and investigates reported sightings of individuals in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Military analysts, linguists and negotiators; civilian archaeologists and anthropologists; and native laborers search for and excavate sites believed to contain the remains of Americans. The Army’s Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii analyzes the evidence, as it does items from World War II with 78,000 Americans unaccounted for and the Korean War with 8,100.

With a $20 million budget and staff of 175 people, the group’s task is to provide the “fullest possible accounting” of the missing. More than 2,500 investigations have led to identification of remains of 158 people. The possible remains of another 407 are being analyzed, and scheduled excavations could bring in 200 more, said Col. Barbara Claypool, task force spokeswoman.

The work will continue “until the American people believe we’ve done everything we can do,” she said.

Almost half of the 2,109 missing Americans in Southeast Asia were reported killed in action, but their bodies have not been recovered and many probably never will be, said Col. Claypool and Ann Mills Griffiths, executive director of the POW league. The rest are presumed dead. And of those, the task force is working hardest on the fate of 131 people who were alive at the time of their last contact with U.S. forces.

Ms. Griffiths, league director for the past 20 years, praises the task force’s work but believes the Vietnamese government is blocking the effort by withholding records and remains. “It’s clear from the evidence that they are not being fully forthcoming,” she said. “The Vietnamese will give this to us when they are ready.”

An excavation of the Huggins crash site by 27 U.S. and Vietnamese workers in early 1995 recovered 403 pieces of human tissue, 81 bone fragments and hundreds of pieces of aircraft and personal equipment. Jet fuel still permeated the subsoil of the 17-foot-deep, muck-filled impact crater. An elephant was called in to yank out a piece of the fuselage.

A 4-inch-long piece of unearthed bone turned out to be the proof Major Huggins’ daughter had been looking for. Army lab investigators determined in June that the bone, a piece of the ulna, genetically matched a sample of blood from Major Huggins’ sister, Mary Whittington of Troy, Alabama.

Because they have no samples of the missing Americans’ DNA for comparison, Army analysts have begun successfully using a test that matches remains with the genetic code of a maternal relative.

“It’s helped us considerably to say the least,” said Sgt. Michael Butts, a lab spokesman, of the mitochondrial DNA test. “We’re using the technique to identify remains we couldn’t in the late 1980s.”

One of those successes cleared the way for the service for Maj. Huggins of Troy, Ala., who spent his last night planning a church revival and whose 16-year military career included stops in Sherman and Austin.

Ms. McIntosh, who wears her “gung-ho lifer” father’s ring, will have her daughter Gayla, 8, on hand Friday for the memories’ sake. “I want her to remember her grandfather being treated as a hero.”

Phillipe Ritter of Fort Worth will make the trip, one he hopes to repeat some day. His father, George Ritter, an Air America pilot, is unaccounted for after a 1971 crash in Laos. But Mr. Ritter, who met Ms. McIntosh through the POW league, learned last week that the task force plans to excavate a potential site.

“This is the first real news my family’s had in the past 25 years. One day I’ll be standing out there” at the national cemetery, he said. “Hopefully.”

Ms. McIntosh said she will be standing there Friday to pay respect and to help keep the war story alive.

“It’s true. The war is over and we need to move on, but there’s still a lot of families with questions,” she said. “They deserve to be able to put their doubts to rest. We’re really lucky.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard