EVER TO REMEMBER

Anthony DeLucia loved to swim almost as much as he loved to fly. For years, his family held out hope that the Army Air Corps flight engineer had paddled his way to a Pacific island after a bomber crash during World War II.

The last time his family saw him was in 1942 during a visit to his hometown of Bradford, 220 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. The Air Corps volunteer gave his brother, Elmer DeLucia, a watch.”He said, ‘Elmer, I’m going someplace real far away and I don’t know when I’ll ever see you again,’ ”

Elmer DeLucia, now 77, said Thursday. “That was the last time I saw him. That was it.”

On August 31, 1944, DeLucia’s 24th birthday, he and nine other airmen were reported missing when their B-24 did not return from a raid on Japanese ships in the former Formosa, now Taiwan.His family figured the bomber had gone into the sea. Japanese records offered no clues, and the Army could not find evidence of a crash. Over the years, Elmer DeLucia lost hope that he would find out what happened to his brother.But in 1996, Chinese farmers found wreckage of the plane while searching for herbs on 7,000-foot Kitten Mountain in Guangxi Province.

The discovery helped the military fulfill a promise it made to families of missing veterans in 1946: to bring home everyone who could be found, no matter what it took. “Even though this gentleman is from a long time ago, he’s still one of our brothers,” said Army Captain Paul Gonthier, who is counseling DeLucia’s brothers, both of whom earned Purple Hearts in World War II.

Elmer DeLucia will lay his brother’s remains to rest Saturday in the family plot in Bradford, a town of 11,000 known for producing oil and Zippo lighters. Six of the other nine airmen will be buried August 2, 2000 at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.

Families of the other men are burying them privately. Last month, the remains of Private Vincent J. Netherwood were buried in his hometown of Kingston, New York. Netherwood, the plane’s tail gunner, was 20 in 1944 and engaged to be married.

U.S. and Chinese searchers spent three years investigating the crash site to help scientists at the Defense Department’s forensic laboratory in Hawaii identify the dead. They used dental records, dog tags, rings and DNA to identify what they could. The rest will be placed in a seventh casket that will be buried in Arlington at the same time as the other six.

Elmer DeLucia flew to Hawaii last week to escort his brother’s casket home. Their mother, Jennie DeLucia, asked Elmer before her death in 1968 to bury Anthony, if he was ever found, alongside his parents near the church where he was baptized. At the funeral, Elmer and another DeLucia brother, Auggie, will receive the Purple Heart their brother earned in the crash.

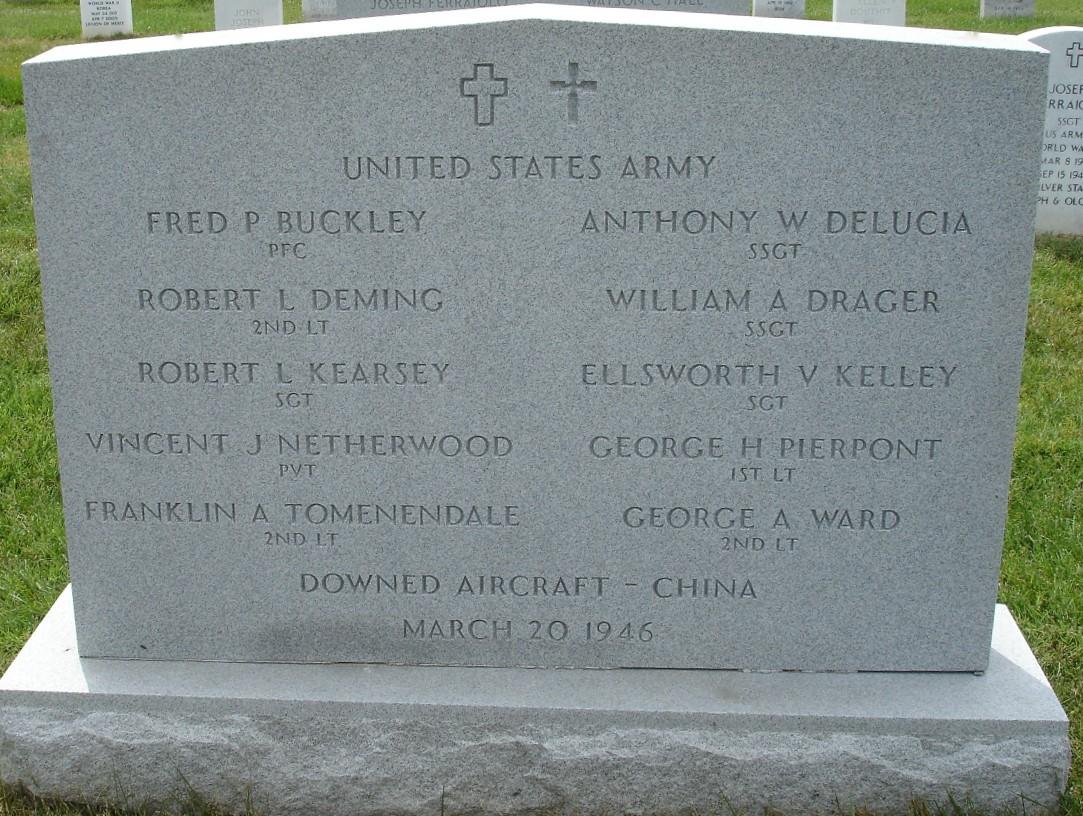

The 10 airmen will be honored with their names listed on a plaque at Arlington above the grave for the remains that could not be identified.

The remaining airmen were identified as First Lieutenan George H. Pierpont of Salem, Virginia; Second Lieutenant Franklin A. Tomenendale of Shabbona, Illinois, Second Lieutenant Robert L. Deming of Seattle, Washington; Second Lieutenant George A. Ward of Jersey City, New Jersey, Sergeant Ellsworth V. Kelley of Newark, Ohio; Private First Class Charles Buckley of Garden City, Kansas; Staff Sergeant William A. Drager of Washington, New Jersey; and Sergeant Robert L. Kearsey of McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania.

Courtesy of The Washington Post:

A Belated but Honorable Homecoming for World War II Bomber Crew

By Steve Vogel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday , August 24, 2000 ; J06

On the evening of Aug. 31, 1944, 2nd Lt. George H. Pierpont, 2nd Lt. Franklin A. Tomenendale and a crew of eight others lifted off in a B-24J Liberator from a base in Liuchow, China, on a mission to bomb Japanese ships anchored in Takao Harbor, Formosa.

They never returned. But Monday at Arlington National Cemetery, the remains of the men who disappeared nearly 56 years ago were finally put to rest during a full military honors funeral.

“The passage of time cannot diminish the memory of 10 brave men, nor can the passage of nearly 56 years diminish our appreciation of their sacrifice,” Lt. Col. James E. May, an Army chaplain, told mourners representing the families of all 10 men inside the Fort Myer Chapel.

After the service, a long procession followed a horse-drawn caisson to the grave sites. A B-52 bomber from the Air Force base in Minot, N.D., flew in salute over the seven caskets draped with American flags, and a lone bugler played taps in belated but heartfelt mourning for the crew.

Pierpont, a native of Salem, Va., was represented by his sister, Nancy Mountcastle, of Monkton, Md.

Six of the men were buried side by side at Arlington–Pierpont; Tomenendale, of Shabonna, Ill.; 2nd Lt. Robert Deming, of Reno, Nev.; 2nd Lt. George Ward, of Inverness, Fla.; Sgt. Ellsworth Kelley, of Wellington, Fla.; and Pfc. Fred Buckley, of Arms, Kan.

A seventh casket, containing the remains of various crew members, was also buried. Four other crew members will be buried at private ceremonies elsewhere: Staff Sgt. Anthony DeLucia, of Bradford, Pa.; Staff Sgt. William Drager, of Pembrooke Pines, Ill.; Sgt. Robert Kearsey, of Jacksonville, Fla.; and Pvt. Vincent Netherwood, of Kingston, N.Y.

After the war, a review of enemy records failed to turn up any trace of the Liberator and its crew. Their whereabouts remained a mystery until November 1996, when Jiang Zemin, president of the People’s Republic of China, presented President Clinton with five identification tags from an aircraft crash site in Guangxi Province.

Four times between 1997 and 1999, a joint U.S.-Chinese team excavated the crash site, recovering numerous pieces of wreckage, personal effects and remains.

Sad though it was, Monday’s ceremony was not unique. Arlington Cemetery holds several crew burials during most years, said superintendent Jack Metzler, including other crews from World War II. “They’re finding more remains all the time,” Metzler said.

Burial services with full military honors were held Monday at Arlington National

Cemetery for the remains of six crew members of a World War II bomber.

The entire 10-man crew of the U.S. Army Air Force B-24J Liberator aircraft

had disappeared August 31, 1944, after taking off from China on a strike mission over enemy ships in Takao Harbor, Formosa, now known as Kao-hsiung, Taiwan.

“I was four months old when all this transpired and for several years there was nothing really known of the crew,” said Jim Drager, a son of one crew member.

“All the families got letters that said, ‘We’re still looking, we’re still looking, don’t give up hope.’ And finally — I think it was two years later — they officially declared them dead,” he said.

But in 1996, Chinese President Jiang Zemin presented U.S. President Bill Clinton with five dog tags and a videotape of a crash site found by two farmers on a remote mountainside in southern China.

“They were found in a crevasse. I think the peak was 7,000 feet,” said David Ward, whose uncle had been on the plane. “The plane hit at 6,500 feet and fell into a granite notch so one could see it.”

Drager accompanied the U.S. Army team that went in to recover the remains.

“All of a sudden we came around a corner on this one ledge and it was as if this plane crashed last week. It still smelled of oil and grease,” he recalled. “I would be picking up boots. I would be picking up different pieces of clothing, equipment. I mean it was all there as if someone had taken it, shaken it, and thrown it in a pile there.”

Several more excavations yielded human bones and dog tags and eventually the remains of all 10 crewmen were identified. The remains of those not buried Monday have been or will be released to relatives.

Elmer DeLucia remembers the last time he saw his brother Anthony. “He said, ‘Elmer, I know you don’t graduate for another year and a half, and I have something for you,’ and he gave me a beautiful wristwatch. He said, ‘I don’t know when I will ever see you again.’ And that’s the last time I saw him.”

Some 78,000 men who served in WWII remain missing.

Lost airman honored after 56 years: 21 August 2000For more than 50 years, the only thing Diana Deming Hale knew for certain about her uncle, Robert Deming, was that she was born the same year his plane crashed.A navigator, 2nd Lt. Deming was aboard a plane that crashed in China on Aug. 31, 1944, after a bombing run during World War II. Government officials told the Demings that the airman was missing in action. His parents told family members they hoped he somehow survived and would find his way home.

Deming Hale remembered seeing photos of her lost uncle displayed in the homes of relatives. But otherwise, she said, she had heard little about him.

“At the time, it just seemed like it was not discussed much,” Deming Hale said. “But I’m proud of him now. I think everybody is.”

Today, the family can find some closure, Deming Hale said. Deming and nine other airmen who died in the crash will be honored in a burial service today at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Deming and five of his fellow crew members will be buried at Arlington after today’s ceremony. The remains of four others will be released or have already been released to their families.

Born in San Francisco, Deming moved with his family to Seattle when he was in high school. He graduated from Franklin High School and attended the University of Washington. Sister-in-law Eleanor Deming remembers the airman as an outgoing man with a lively sense of humor. He was also proud to serve his country, she said.

“He was eager to get into the war and do what he could do,” Eleanor Deming said.

Robert Deming, who was 29 at the time of the crash, had been in the Army for only about a year, Eleanor Deming said. A bombing attack on Takao Harbor in Taiwan was his last mission. The B-24 helped pound Japanese boats and docks and then headed home, but it crashed into 7,000-foot Kitten Mountain in Guangxi province. The plane likely went undisturbed until discovered four years ago, when two Chinese farmers found the crash site while searching for rare herbs.

Military officials have spent the intervening years gathering and identifying the remains of Deming and the others, which were most recently examined at the Department of Defense’s forensic laboratory in Hawaii.

But with the exception of Deming’s older brother, Joseph, his immediate family did not live to hear what became of the airman.

Deming, who was married briefly and then divorced, had no children. His parents and younger brother, David – who was Diana Deming Hale’s father – died before hearing about the discovery of the plane. Joseph Deming lived to hear about the discovery of the plane but died three years ago.

Joseph Deming’s son David will represent the family at Arlington. The government flew him, his wife, Marsha, and their son John-David to Washington, D.C., to attend the service.

The other airmen on the bomber were identified as Sgt. Robert Kearsey of Jacksonville, Fla.; Staff Sgt. Anthony DeLucia of Bradford, Pa.; 1st Lt. George Pierpont of Salem, Va.; 2nd Lt. Franklin Tomenendale of Shabbona, Ill.; 2nd Lt. George Ward of Jersey City, N.J.; Sgt. Ellsworth Kelley of Newark, Ohio; Pfc. Charles Buckley of Garden City, Kansas; Staff Sgt. William Drager of Washington, N.J.; and Private Vincent Netherwood of Kingston, N.Y.

Local airman killed in ’44 to be honored at Arlington

Sunday, August 20, 2000

The full story of the four fighting Kearseys of McKees Rocks will never be known.

Entire chapters are lost forever, blown away by the winds of war. But now, almost 56 years after the Army Air Forces announced that the oldest of the brothers was missing in action, his biography will finally have an ending.

Sgt. Robert L. Kearsey will be honored tomorrow in a burial service at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va. Too bad none of his brothers are alive to see the ceremony.

Born in Albany, Ga., the Kearsey boys were a close bunch. One by one they trooped to McKees Rocks to find work during the Great Depression. Their jobs in Western Pennsylvania ended when they marched off to war together.

All four went into battle at once. Three became airmen and, in an unusually cruel twist, two of them disappeared in action.

Now, through happenstance and DNA science, we know that Robert Kearsey was killed on Aug. 31, 1944, after a bombing raid in what is now Taiwan. Kearsey and his nine crew mates were flying back to their home base in China when something went terribly wrong.

Their B-24J Liberator crashed into Kitten Mountain, one of the taller peaks in southern China. All of them died instantly, though five decades passed before anybody could verify that.

The remains of the airmen were not discovered until 1996. Farmers found the skeletons while hunting for rare herbs on the 7,000-foot mountain.

After more than three years of searching the mountain and DNA analysis by the U.S. Army, most of the remains have been identified and returned to the United States.

Remains from the crash that cannot be linked to specific individuals will be placed in a common plot in Arlington. Six of the 10 airmen also will buried there.

Kearsey will be buried later in Jacksonville, Fla., where his family now lives and where a plot has been set aside to memorialize him and his brothers.

Another Pennsylvanian who was on the fatal mission with Kearsey, Staff Sgt. Anthony DeLucia, was buried this month in his hometown of Bradford, McKean County.

Kearsey, 27 when he died, never married. He had no children. His nieces and nephews will attend the services in Arlington to pay tribute to him.

They consider him a hero for accepting dangerous duty he could have avoided.

Robert was a natural leader, the one who started the Kearsey family exodus from the rural South to the Pittsburgh area. His brothers — Gordon, Grady and Joseph — followed him to Western Pennsylvania, where the slag-covered hills glowed with the promise of steady paychecks.

All of them tasted a small slice of prosperity, landing work in factories, but Japanese attackers and Adolf Hitler made sure they did not find peace. By 1943, all the brothers were at war.

Grady Kearsey, a member of the Army Air Forces, was killed that summer when his plane was shot down over Kiel, Germany. His body was never found.

Grady’s death did not make the Kearsey clan eager to come home. If anything, it motivated the brothers to fight harder.

Robert, an airman like his fallen brother, was transferred from an overseas assignment to Langley, Va., after Grady’s death. He was to ride out the war there as a gunnery instructor, but he felt guilty about taking an assignment on the home front. He wanted to go back to war, to fight for Grady.

“His motivation was to get even,” said Grady Robert Kearsey, 56, a nephew named after both uncles who died in the war.

The Army was not about to reject such a request from an experienced airman. So it shipped Robert Kearsey to the Pacific.

An attack on Takao Harbor in Taiwan turned out to be his last mission. It went well for American bombers, who pounded the Japanese boats and docks. Then they headed home in a rough thunderstorm.

Most of the men on Kearsey’s crew were young and inexperienced, but nobody knows if that was a factor in the B-24 crashing into the mountain.

The airmen had come under heavy fire during the raid, and their plane may have been disabled. Another possibility is that they encountered enemy fliers who took them down or caused them to crash.

Because all the witnesses died together, no one will ever know what went wrong.

Gordon Kearsey’s new wife in McKees Rocks opened the telegram that told of Robert’s plane disappearing. Cecelia Kearsey then wrote the two surviving brothers with the bad news.

“I hated telegrams,” said Cecelia, now 78 and living in Jacksonville Beach, Fla. “I received three of them in the war and I shook every time. The first one said my sister’s husband had been killed. The next one was about Grady and the last one said Robert was missing.”

Her husband, a Navy pilot, was the third Kearsey brother who served as an airman. Gordon Kearsey made it home from war, but his life was short. He died of a heart attack at 44.

“My dad was haunted by losing two brothers in the war,” said Grady Robert Kearsey. “He never even got to give them a funeral.”

The youngest of the brothers, Joseph, served as an Army infantryman.

He survived the war, but also died relatively young, at 52.

The family hasn’t picked a date yet, but some time after returning from Arlington it will hold another service.

Robert Kearsey’s remains will be placed in the Jacksonville cemetery where Gordon is buried and Joseph’s ashes are held.

“We’re going to add a plaque for Uncle Grady, too,” the nephew said.

WWII Army air crew laid to rest

by Sharon Walker

WASHINGTON (Army News Service, Aug. 23, 2000) — A crew of 10 young Army aviators returned to a friendly base this week and were laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery almost 56 years to the day after they set out on their World War II mission.

Second Lt. George H. Pierpont and 2nd Lt. Franklin A. Tomenendale piloted the B-24 “Liberator,” a heavy bomber aircraft capable of long operating ranges. After taking off from an airfield in Liuchow, China, Aug. 31, 1944 to bomb enemy ships, according to a military report, “The aircraft never returned to a friendly base.”

Along with pilot and co-pilot, the flight manifest included 2nd Lt. Robert Deming, 2nd Lt. George A. Ward, Staff Sgt. Anthony DeLucia, Staff Sgt. William A. Drager, Sgt. Robert L. Kearsey, Sgt. Ellsworth V. Kelley, Pvt. Fred P. Buckley and Pvt. Vincent J. Netherwood. Pierpont, the pilot, was promoted to first lieutenant Sept. 1, 1944, the day after he was reported missing.

Family members and acquaintances – young and old – gathered Aug. 21 at the Fort Myer Post Chapel for a group funeral service. There, Chaplain (Lt. Col.) James E. May said that 56 years cannot diminish the memory nor the service given by the 10 men.

“We can consecrate this moment in time,” May said, “and give thanks for the impact their brief lives have on us all. We can give thanks for their noble service.”

“They touched our lives,” said Chaplain (1st Lt.) Boguslaw A. Augustyn, “and we pray for their peace and happiness today, tomorrow and the day after.”

The Protestant and Catholic chaplains each read from the Old and New Testaments, from Psalms 139: 1-12 and 23-24, and from Romans 8: 31-39.

Six of the soldiers were interred at ANC immediately following the chapel service. In addition to the six burial vaults holding the remains of the men, there is a seventh vault to represent and memorialize the entire crew. It bears the inscription “Ever to remember, August 31, 1944.”

The 3rd U.S. Infantry (The Old Guard) performed full military honors, and a B-52 bomber from the 5th Bomber Wing, Minot, N.D., flew over the gravesite.

In 1948, four years after the B-24’s fateful flight, the Department of the Army amended the crew’s status from “Missing in Action” to “Killed in Action, Remains Not Recoverable.” No evidence of the aircraft was found during or after the war until

sometime in the fall of 1996 when two Chinese farmers discovered the crash site.

In November 1996, People’s Republic of China President Jiang Zemin presented President Bill Clinton with five identification tags recovered from an aircraft crash site in Guangxi Province. The names on the military dog tags included those of Buckley,

Kelley, Netherwood, Tomenendale and Ward.

A team from the Army’s Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii launched a search in January 1997, recovering “…human remains and artifacts from the site…” according to a CILHI report. The team also documented aircraft wreckage bearing the stenciled numbers “40783,” the serial number that identified the aircraft of Pierpont and crew.

Bad weather limited the CILHI team to late summer and early fall excavations, and they returned in 1998 and 1999, each time recovering more evidence of the downed crew including dog tags, personal effects and human remains. During August and September 1999, U.S. and Chinese authorities teamed up to complete the excavation.

A copy of an aged photograph was one of the sole pieces of present-day evidence of these men’s connection to one another. The crew had gathered in front of their aircraft. Decked out in flight jackets, they were all smiles.

But the evidence of their connection was also apparent in the gentle pats on the back of one family member to another, strangers before the ceremony. And it was apparent in the teenage grandchildren and older nephews and nieces who heard the stories and knew they had a hero in their lineage.

Elmer DeLuca

Sergeant, United States Army Air Corps

Vincent J. Netherwood

Private, United States Army Air Corps

George H. Pierpont

First Lieutenant, United States Army Air Corps

Franklin A. Tomenendale

Second Lieutenant, United States Army Air Corps

Robert L. Deming

Second Lieutenant, United States Army Air Corps

George A. Ward

Second Lieutenant, United States Army Air Corps

Ellsworth V. Kelley

Sergeant, United States Army Air Corps

Charles Buckley

Private First Class, United States Army Air Corps

William A. Drager

Staff Sergeant, United States Army Air Corps

Robert L. Kearsey

Sergeant, United States Army Air Corps

“I Once Was Lost, But Now Now I’m Found…”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard