U.S. Department of Defense

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs)

News Release

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 0344-08

April 25, 2008

Missing WWII Airmen are Identified

The Department of Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) announced today that the remains of 11 U.S. servicemen, missing in action from World War II, have been identified and will be returned to their families for burial with full military honors.

They are Captain Robert L. Coleman, of Wilmington, Delaware; First Lieutenant George E. Wallinder, of San Antonio, Texas; Second Lieutenant Kenneth L. Cassidy, of Worcester, Massachusetts; Second Lieutenant Irving Schechner, of Brooklyn, New York; Second ieutenant Ronald F. Ward, of Cambridge, Massachusetts; Technical Sergeant William L. Fraser, of Maplewood, Missouri; Technical Sergeant Paul Miecias, of Piscataway, New Jersey; Technical Sergeant Robert C. Morgan, of Flint, Michigan; Staff Sergeant Albert J. Caruso, of Kearny, New Jersey; Staff Sergeant Robert E. Frank, of Plainfield, New Jersey; and Private Joseph Thompson, of Compton, California all U.S. Army Air Forces. The dates and locations of the funerals are being set by their families.

Representatives from the Army met with the next-of-kin of these men in their hometowns to explain the recovery and identification process and to coordinate interment with military honors on behalf of the secretary of the Army.

On December 3, 1943, these men crewed a B-24D Liberator that departed Dobodura, New Guinea, on an armed-reconnaissance mission over New Hanover Island in the Bismarck Sea. The crew reported dropping their bombs on target, but in spite of several radio contacts with their base, they never returned to Dobodura. Subsequent searches failed to locate the aircraft.

In 2000, three Papua New Guineans were hunting in the forest when they came across aircraft wreckage near Iwaia village. The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) was notified and began planning an investigation. In 2002, a JPAC team traveled to Deboin Village to interview two individuals who said they knew where the crash site was. However, the witnesses could not relocate the site.

In 2004, the site was found about four miles from Iwaia village in Papua New Guinea where a JPAC team found an aircraft data plate that correlated to the 1943 crash.

Between 2004 and 2007, JPAC teams conducted two excavations of the site and recovered human remains and non-biological material including some crew-related artifacts such as identification tags.

Among dental records, other forensic identification tools and circumstantial evidence, scientists from JPAC and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory also used mitochondrial DNA and dental comparisons in the identification of the remains.

For additional information on the Defense Department’s mission to account for missing Americans, visit the DPMO Web site at http://www.dtic.mil/dpmo or call (703) 699-1169.

25 April 2008:

DOVER, Delaware – The remains of 11 airmen whose bomber disappeared during a World War II mission over the southwestern Pacific have been identified and are being returned for burial with military honors, Pentagon officials said Friday.

The men were members of the Army Air Forces 43rd Bomber Group, 63rd Bomber Squadron. They were listed as missing after their B-24 Liberator, the Swan, failed to return from a mission on December 3, 1943.

The crew had departed from New Guinea on a reconnaissance mission over New Hanover Island in the Bismarck Sea. They reported dropping their bombs on target but, despite several radio contacts with their base, never returned.

The remains were recovered between 2004 and 2007 after members of the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command located and excavated a site on New Guinea where wreckage had been spotted by native hunters four years earlier.

Scientists from JPAC and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory used mitochondrial DNA and dental records to positively identify some of the remains, the military said. Some of the crewmen were also identified through circumstantial evidence, including identification tags.

Kathleen Lund — sister of Second Lieutenant Ronald F. Ward of Cambridge, Massachusetts — said searchers found two of his rings at the crash site, including Ward’s high school graduation ring.

“This is going to be such a closure for my family,” said Lund, who lives near Boston.

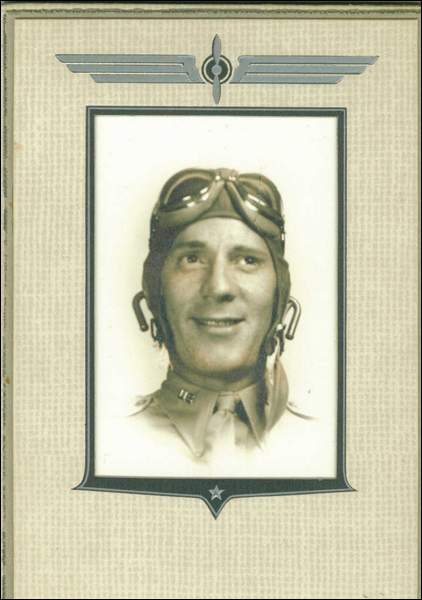

The pilot, Captain Robert Coleman, was an athletic instructor from Wilmington, Delaware, who enlisted in September 1941. Military officials said Coleman’s family did not wish to comment.

In addition to Ward and Coleman, the airmen have been identified as First Lieutenant George E. Wallinder of San Antonio; Second Lieutenant Kenneth L. Cassidy of Worcester, Massachusetts; Second Lieuenant Irving Schechner of New York; Technical Sergeant William L. Fraser of Maplewood, Missouri; Technical Sergeant Paul Miecias of Piscataway, New Jersey; Technical Sergeant Robert C. Morgan of Flint, Michigan; Staff Sergeant Albert J. Caruso of Kearny, New Jersey; Staff Sergeant Robert E. Frank of Plainfield, New Jersey; and Private Joseph Thompson of Compton, California.

A funeral for Morgan was held Thursday in Holly, Michigan, followed by burial at Great Lakes National Cemetery.

Donald Morgan of Flushing, Michigan, who was 11 when his brother died, described him as “a great guy” who wanted to go to college and study engineering.

Morgan said his brother’s remains were identified through analysis of a piece of bone less than an inch long.

A group casket will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia and be marked by a headstone with all 11 names, said Larry Greer, a spokesman for the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office.

“In a larger group like this, there is always hundreds of skeletal fragments that could not be individually identified. Those are collected in a group and placed in a single casket,” he said.

Robert L. Coleman

Captain, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 0-789137

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: Delaware

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Ronald F. Ward

Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 0-736737

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: Massachusetts

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

George E. Wallinder

First Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 0-662400

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: New York

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Kenneth L. Cassidy

Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 0-802017

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: Massachusetts

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Ken Belisle never knew the father who was reported missing in action 64 years ago.

But today the Jacksonville, Florida, resident has his father’s wedding ring, dog tags and identification bracelet found when the remains of 11 U.S. servicemen – including his father, Second Lieutenant Kenneth L. Cassidy of Worcester, Massachusetts – were recently recovered.

The Department of Defense announced the recovery and identification Friday. The remains are being returned to the U.S. for burial with military honors. A group casket will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia and marked by a headstone with all 11 names.

Belisle was born about six months after his father was reported missing in action during World War II in the Southwest Pacific. He had been told by his mother that the Army Air Corps believed the B-24D Liberator on which his father was the co-pilot had crashed at sea.

There was little hope any remains of the crew would be recovered from the depths of the ocean.

The plane had taken off from Dobodura, New Guinea, on December 3, 1943, in an armed-reconnaissance mission over New Hanover Island in the Bismarck Sea.

The crew reported dropping its bombs on the target, but the plane failed to return. The aircraft could not be located on subsequent searches.

In 2000, three Papua New Guineans were hunting in a forest when they came upon aircraft wreckage near Iwaia village. The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command began an investigation and a team traveled to the village in 2002 to interview witnesses. However, they could not relocate the site.

Another team located the site 4 miles from the village in 2004. They found an aircraft data plate that correlated with the 1943 crash.

Over the next three years, command teams conducted excavations of the site and recovered human remains and some crew-related objects such as ID tags and jewelry. Investigators then used DNA, forensic tools and dental records to identify the remains.

Belisle said he was first notified by the POW/Missing Personnel Office in 2004 when the search team found the site.

“They included a photograph where you could clearly see the tail of the plane,” he said.

The crew apparently got lost after the bombing run and crashed into the side of a mountain 80 miles north of the airfield, Belisle said. Heavy jungle growth protected the wreckage from the elements.

After his father was declared dead, his mother remarried an Army officer, Maurice Belisle, whom Belisle considers his father.

“He is an amazing man at age 95 and lives in Fort Myers,” Belisle said. His mother died in 1995. The elder Belisle was a career Army officer who was awarded two Silver Stars.

“I changed my name to his, but he decided he shouldn’t adopt me so my mother wouldn’t lose the Army benefits she received on my behalf,” Belisle said.

The Army called Belisle again last spring because they intended to do DNA tests on the remains. He directed them to his uncle, Robert Cassidy.

In November, an Army casualty assistance officer spent five hours with Belisle giving him information, evidence and photographs so he could sign an agreement acknowledging they were his father’s remains.

“This was all a surprise to me because I never even knew him,” Belisle said. “I’ve got two brothers and a sister from my stepfather and mother and we have a wonderful family relationship.”

He also was surprised because he thought his father had crashed at sea. “I never expected to hear anything,” he said.

Belisle, a 1967 graduate of the Naval Academy, applied to Annapolis as the son of a deceased veteran. After flight school, he served with VP 16 at Jacksonville Naval Air Station. He was a commercial pilot for Eastern and Northwest airlines and continued in the Navy Reserves, serving for eight months as commander of Navy Region Southeast, the first reserve rear admiral to have the command. He retired in 2004.

“When I look back, I think I had the extraordinary opportunity given to me by two different men in my life. My father’s death in World War II gave me the opportunity to go to the Naval Academy and my stepfather became my role model and provided me with everything I needed,” he said.

“I was doubly blessed with two men who did things in different ways that really guided the course of my life.”

Kenneth Belisle of Florida never knew his biological father, Second Lieutenant Kenneth L. Cassidy, co-pilot of a World War II bomber, but he understands why the return of the remains of his father and his crewmates, missing since 1943, means so much to people.

“People like to see closure, even if it’s not their particular relatives,” said Mr. Belisle, a retired Navy two-star Rear Admiral. “I think that’s really important. … All of the people I’ve talked to and who are involved in that process are really committed.”

The Department of Defense announced Friday that the remains of the 11 crewmen of the Swan, a B-24D Liberator bomber, were coming home. The plane disappeared on Dec. 3, 1943, while on a reconnaissance mission over the Bismarck Sea off Papua New Guinea.

Mr. Belisle, 63, a Worcester native living in Jacksonville, Florida, was born after his father’s plane vanished. “I never thought we would ever see anything, because even the military told my mother that they thought they went down over water,” he said. Three or four planes searched for 18 hours, he said.

The rescuers were in the wrong place. In 2000, Papua New Guinean hunters found the plane in the jungle. They couldn’t relocate it when a Department of Defense team visited in 2002, but it was rediscovered in 2004. The “triple canopy jungle” kept the site hidden, but it also protected some of the remains, Mr. Belisle said.

The military positively identified his father’s remains using a DNA sample from Mr. Cassidy’s brother, Robert, formerly of Culpeper, Virginia. Robert Cassidy has since died, as have his other siblings, according to Robert Cassidy’s widow.

Mr. Belisle’s mother, Jeanne, remarried after several years. Mr. Belisle’s stepfather, Maurice Belisle of Fort Myers, Florida, is a retired Army Colonel who served in World War II and has relatives in Worcester.

“I have a great deal of respect for what my biological father did … but my stepfather did the same thing, so he’s a hero, too, to me,” Mr. Belisle said. “Between the two of them, they guided my life.”

Mr. Belisle does not know whether his father will be buried as part of a group ceremony or individually, and the location is still being worked out.

Irving Schechner

Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 0-673737

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: New York

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

William L. Fraser

Technical Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 17035406

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: Missouri

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

William Lee Fraser of Maplewood was the radio operator on a B-24 bomber that crashed into the jungle of New Guinea on the night of Dec. 3, 1943. Two weeks later, a brief newspaper article listed him as missing.

Tech. Sgt. Fraser, Army Air Forces, was 22 when he died. He had been overseas barely two months. The government, unable to find the bomber, declared him officially killed in action in January 1946.

Almost 61 years later, an American search crew found the wreck.

The Department of Defense announced Friday that it had identified remains of the Liberator’s 11 crew members. It contacted surviving relatives in February.

“This came up real sudden for us,” said Albert Blair, a cousin who lives in Eldorado, Ill., 130 miles southeast of St. Louis. “It had been a long, long time. I guess the government will just keep looking until they find something.”

Blair said Fraser was the only child of the late Robert L. and Beatrice Fraser, who lived in the 7600 block of Manchester Avenue. He said Fraser, eight years his senior, attended Maplewood High School. Fraser joined the Army Air Forces on Jan. 13, 1942, five weeks after the United States entered World War II.

Larry Greer, a spokesman for the military’s POW/Missing Personnel Office in Washington, said Fraser’s B-24 flew from a coastal air base in southeastern New Guinea on a mission across the Bismarck Sea to New Hanover Island. For nearly two years, American and Australian forces had been battling the Japanese across the islands north of Australia. The Americans had taken Guadalcanal to the east 10 months before.

Greer said the four-engine Liberator reported by radio that it had dropped its bombs on a Japanese ship convoy and was headed home.

“There were two other transmissions,” Greer said. “The second was, ‘We’re close to home, how about turning on the runway lights?’ The last was, ‘It’s dark. Where the … are the … lights?'”

Greer said other air crews searched for the B-24 without success. In 2000, three hunters reported finding a wreck but were unable to retrace their route for an American crew.

A search team found it in 2004, verified the plane and collected remains. Greer said the team used DNA and other information to identify remains from all 11 crewmen.

Blair said his family is planning a burial in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery and will take part in a common-grave ceremony with the other families at Arlington National Cemetery across the Potomac River from Washington. Greer said the government allows for both. No dates have been set.

Blair said Fraser’s mother, “Aunt Bea,” for years kept a Purple Heart the government gave her on behalf of her missing son.

Blair, who grew up in Webster Groves, moved to Eldorado shortly after the war. He said his two brothers and three sisters, who are Fraser’s other closest survivors, are James Blair of Ballwin, William Blair of Arnold, Evelyn Ode of Webster Groves, Flora Canepa of Affton and Faye Ferguson of Indianapolis.

Paul Miecias

Technical Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 32302997

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: New Jersey

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Robert C. Morgan

Technical Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 16039363

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: Michigan

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Albert J. Caruso

Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 32464441

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: New Jersey

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

The plane, it turned out, was near the airfield, but headed the wrong way. It crashed into the side of a mountain, burst into flames, and was declared missing — a fate met by hundreds of World War II planes.

More than 60 years passed and then Norma Rowe of East Hanover got a phone call about her uncle, Staff Sergeant Albert J. Caruso, who left Kearny to fight in the war and never returned.

“The woman said she worked for the Army,” Rowe said. “She wanted a sample of my DNA.”

She was told wreckage of a plane had been discovered and members of the military’s Joint Pow/MIA Accounting Command had unearthed the crash site, analyzed the human remains and collected artifacts such as dog tags, rings and jewelry.

Yesterday, the Pentagon announced that a four-year recovery effort had been a success — all crew members had been accounted for and their families notified. The crew of the Swan, the Pentagon said, is coming home. The remains of nine of the 11 crew members will be buried side by side at Arlington National Cemetery in July.

Those arrangements make sense to Marlene Moore, a teacher from Mathews, Virginia, and one of the few remaining relatives of Staff Sergeant Robert E. Frank, a crew member from Plainfield.

“I chose for Uncle Bob to be buried next to his buddies,” she said. “They’ve been together all these years. They should stay together.”

Robert E. Frank

Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 32303093

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: New Jersey

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Joseph Thompson

Private, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 19039138

63rd Bomber Squadron, 43rd Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered the Service from: California

Died: 20-Jan-46

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard