United States Dpeartment of Defense

IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 20, 2003

Crew of World War II U.S. Navy Aircraft Found, Identified

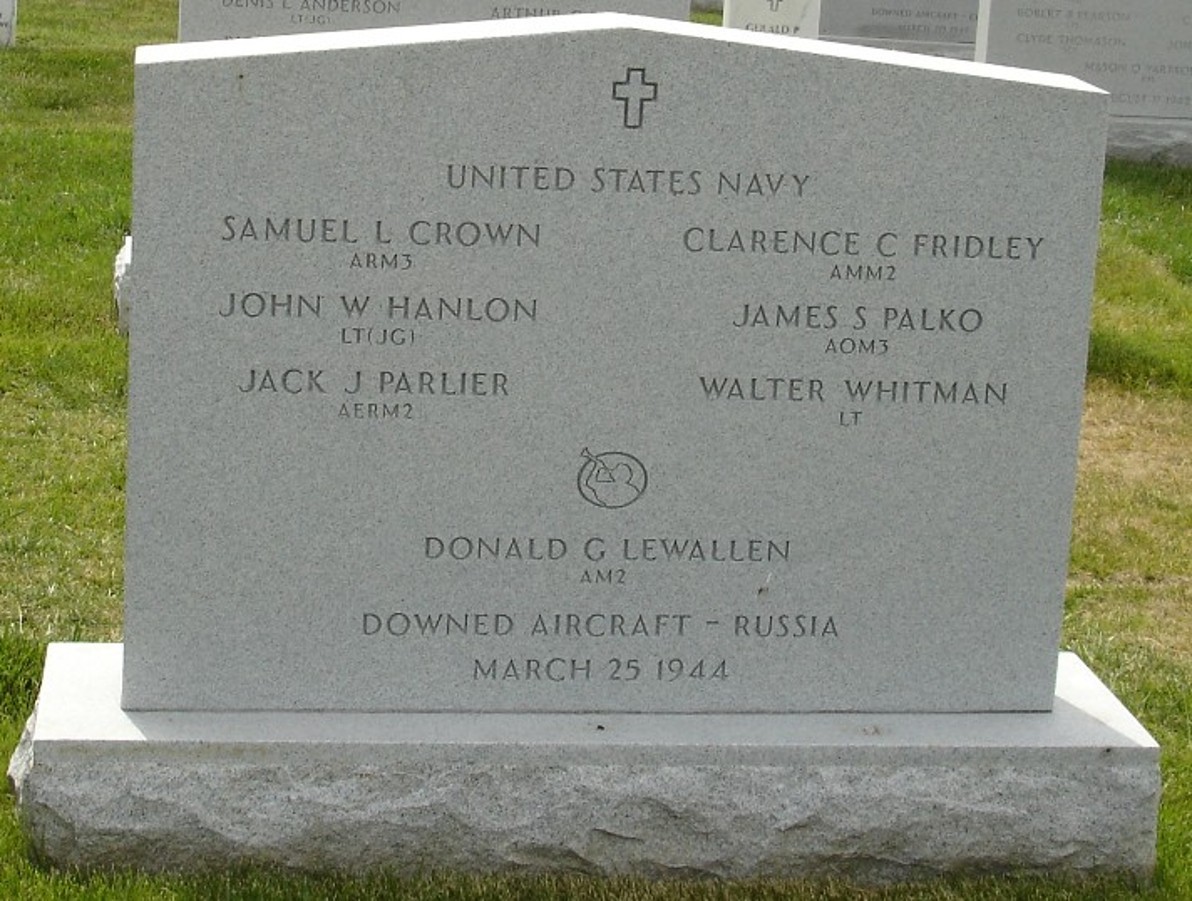

The remains of seven American servicemen missing in action from World War II have been found in Russia, identified and returned to their families for burial with full military honors. A group burial of the remains will be held at Arlington National Cemetery on Thursday, November 20, 2003.

The seven Navy aircrew members are identified as Lt. Walter S. Whitman Jr. of Philadelphia, Pa.; Lt. j.g. John W. Hanlon Jr. of Worcester, Mass.; Petty Officer 2nd Class Clarence C. Fridley of Manhattan, Mont.; Petty Officer 2nd Class Donald G. Lewallen of Omaha, Neb.; Petty Officer 2nd Class Jack J. Parlier of Decatur Ill.; Petty Officer 3rd Class Samuel L. Crown Jr. of Columbus, Ohio and Petty Officer 3rd Class James S. Palko of Superior, Wis.

On March 25, 1944, Whitman and his crew took off in their PV-1 Ventura bomber from their base on Attu Island, Alaska, headed for enemy targets in the Kurile Islands of Japan. The aircraft was part of a five-plane flight which encountered heavy weather throughout the entire mission. About six hours into the mission, the base at Attu notified Whitman by radio of his bearing. There was no further contact with the crew. When Whitman’s aircraft failed to return, an over water search was initiated by surface ships and aircraft in an area extending 200 miles from Attu, but no wreckage was found.

In January 2000, representatives of the U.S.-Russia Joint Commission on POW/MIAs received a report from a Russian citizen who had discovered wreckage in 1962 of a U.S. aircraft on the Kamchatka peninsula on the east coast of Russia. Later that year, specialists from the Central Identification Laboratory Hawaii (CILHI), along with members of the commission, found the wreckage and some human remains.

The following year, the team returned to the crash site to conduct an excavation. They recovered additional remains, artifacts and aircrew-related items which correlated to the names on the manifest of the PV-1.

Between 2001-2003, CILHI scientists employed a wide range of forensic identification techniques, including that of mitochondrial DNA, to confirm the identity of crewmembers. More than 78,000 servicemen are missing in action from World War II.

Deerfield Beach private eye finds answers to 1944 U.S. Navy bomber crash

Private eye Shirley Ann Casey took on a mystery that had stumped Navy officials and police. But sure enough, it was the tenacious Casey, a gumshoe at 52, who cracked the case.

It would prove to be the case of a lifetime — a mystery spanning nearly 60 years that began on a snow-covered volcano in Russia, thousands of miles from Casey’s home in Deerfield Beach, where she did most of her sleuthing.

Partly because of her efforts, a burial ceremony honoring World War II bomber pilot Lt. Walt Whitman and his crew of six will take place Thursday at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Standing in the crowd will be Casey, representing the family of Philadelphia-born Whitman. One cousin on Whitman’s paternal side was too ill to travel, and one on his maternal side wished to remain anonymous and had no desire to attend.

“This story touched my heart,” said Casey, who has no family in the military but volunteered her services to the Navy two years ago after reading about the military’s unsuccessful search for relatives of a World War II pilot.

“We were running up against a brick wall,” said Ken Terry, head of the POW/MIA section for Navy Casualty, a division of the Navy Personnel Command in Millington, Tenn.

“We could not find relatives of Lt. Walt Whitman. That’s where Miss Casey came into play. She put in hundreds of hours unraveling this mystery. She was able to find clue after clue. She was piecing together this massive puzzle trying to run down a lead for a maternal relative. Without that maternal relative, we would not be at this point. We’d still be searching.”

Casey leaves today for Arlington to attend the 11 a.m. ceremony Thursday for Whitman and his crew.

Although only three of the men have been identified, the ceremony will honor all seven.

“Just being there is an honor,” said Casey. “Such an emotional, overwhelming honor.”

Whitman and his crew of six vanished into an icy fog on March 25, 1944, while on a bombing and reconnaissance mission to Japan from Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. A team of Russian geologists discovered the crash site in 1962, but the Cold War kept the KGB from alerting U.S. officials.

The fate of the crew was a mystery until three years ago, when Russian officials notified the United States of a missing PV-1 Ventura, a twin-engine patrol bomber that crashed nearly 60 years ago on the Kamchatka Peninsula in Siberia.

The bomber was one of five assigned that cold March night to fly 1,500 miles roundtrip to Shumshu Island in the Northern Kurils on a bombing mission, then head back home. The route, known as the “Empire Express,” was flown repeatedly in the final two years of World War II.

Only one plane completed the mission. One crashed on takeoff, and two were forced to turn back. The fifth, carrying Whitman and his crew of six, vanished. Navy officials think Whitman, his engines riddled with gunfire, was trying to reach an emergency landing strip in Soviet territory.

Whitman’s crewmates included co-pilot John Hanlon Jr. of Worcester, Mass.; Samuel Crown Jr. of Columbus, Ohio; Clarence Fridley of Manhattan, Mont.; Donald LeWallen of Omaha, Neb.; James Palko of Superior, Wis.; and Jack Junior Parlier of Decatur, Ill.

After excavation of the crash site, DNA comparisons were made of the lost crew and relatives. Both paternal and maternal bloodlines were required for a complete DNA search.

But the Navy, which even sought help from Miami Beach police, ran into trouble hunting down maternal relatives of the pilot, who was 25 at the time of the crash. His personnel file mentioned only an aunt living in Miami Beach.

“I thought, `Let’s find her,'” said the spirited Casey, her sharp blue eyes flashing. “People aren’t missing to me. They’re just relocated.”

Casey, a Boston native who has been tracing people for a living since 1990, works as a detective for a financial firm in West Palm Beach. In her spare time she finds missing persons, from crime victims to biological parents to hard-to-find heirs.

The search for Whitman’s aunt was frustrating, with one dead end after another. But Casey persevered.

According to her research, Whitman left Philadelphia at age 3 after his parents divorced. He moved with his mother and her new husband to Texas, then to St. Louis as a teenager to live with relatives after his mother’s death. With his aunt’s help, he entered the University of Cincinnati before joining the Navy for training as a pilot.

The aunt, Frances Williams McClain, married four times and lied about her age, leaving a confusing paper trail, Casey said.

“No one could find her,” Casey said. “It took me 11 months. This family had a common name, and there were so many twists and turns. When I found Frances, I knew I’d be home free.”

The aunt died in 1977 at age 92, but Casey was able to trace a cousin mentioned in her will. More than 5,200 men shared the cousin’s name in one state alone, but knowing his age narrowed the search.

Finally, Casey made a phone call, praying she’d found the cousin of the ill-fated pilot.

“I almost fell out of this chair,” she said from her home office, a box marked “Whitman case” at her feet. “I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t expect to find him for two to three years.”

The cousin was willing to provide the Navy with a blood sample but demanded anonymity.

Had it not been for Casey’s work tracking down a DNA sample from the maternal bloodline, the DNA investigation would have been inconclusive, said Terry of Navy Casualty.

“The remains might have included Walt Whitman’s, and we would have never known.”

But they didn’t. Only the remains of Fridley, LeWallen and Palko were found in the wreckage.

Because the other four airmen were not found, Navy officials think they may have survived the crash.

Despite the ceremony in Arlington, this case remains open, Terry said. He and his team will continue to research the fate of the other crew members, including Whitman, just as they hope eventually to find the 78,000 World War II soldiers who remain missing.

“When you’re in boot camp, they tell you that if you fall in the field and we can’t get to you immediately, we will recover your remains and bring you home,” said Terry, a retired Marine. “This is an extension of that promise: We will not forget you.”

Nor did Whitman’s aunt forget her nephew.

In 1945, a year after the crash, she purchased a gravesite for him in Oak Hill, Ohio. It still awaits his remains.

Friday November 21, 2003

Bomber crew lost abroad in WWII is interred

Philadelphia native Walter S. Whitman was among those who had vanished over the Soviet Union.

Almost 60 years after his Navy bomber disappeared into the night sky over the Soviet Union in World War II, Philadelphia native Walter S. Whitman and his six-member crew were buried with honors yesterday during a group funeral service at Arlington National Cemetery.

Lieutenant Whitman, the PV-1 Ventura bomber’s pilot, and his six-member crew disappeared March 25, 1944, while en route to the Kuril Islands of Japan from their base on Attu Island in Alaska. The men were heading there on a reconnaissance and bombing mission when they were apparently hit by Japanese antiaircraft guns.

For more than 55 years, the crew was listed as missing in action, their fates unknown, until January 2000, when the U.S.-Russia Joint Commission on POW/MIAs became aware of a report that a Soviet geological team had stumbled upon the bomber’s wreckage on the side of a Russian volcano in 1962.

The discovery of the crash site – in Russia’s far-eastern Kamchatka Peninsula – had been kept secret during the Cold War, Navy officials said yesterday.

“But once they [Joint U.S.-Russia Commission] became aware of it, it became a success story for them,” said Ken Terry, who heads the POW/MIA section of the Navy Casualty, which helps families and relatives of unaccounted Navy officers.

U.S. forensic specialists traveled to the Kamchatka Peninsula to examine the site and retrieved remains for some of the seven crew members.

The remains were sent back to the United States, where they were put through a complex identification process that included mitochondrial DNA analysis (a method often used when dealing with environmentally challenged samples, such as identifying victims of mass disasters or exhumed human remains).

But Navy officials were hitting a major stumbling block in determining whether Whitman was on that flight, mainly because they couldn’t track down his relatives.

Enter Shirley Casey, a private investigator from Florida, who read about the case in her local paper and volunteered to trace Whitman’s personal history.

In an interview yesterday, Casey said it took her 11 months, but she finally was able find relatives on Whitman’s mother’s side.

Casey also found that Whitman was born in Philadelphia in 1918, but lived in the city only a short time. His father and mother divorced when Whitman was younger than 3, and he moved with his mother to San Antonio, Texas.

After his mother’s death – Casey said Whitman was likely still in high school at the time – he went to live with relatives in Missouri.

Among the things Casey discovered while tracking down Whitman’s case was that there has been a grave in Ohio waiting for him since 1945.

At yesterday’s funeral at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, Casey represented the Whitman family.

“It was very nice,” she said. “I’m glad I could help bring closure to the seven families.”

Aside from Whitman, the PV-1 Ventura crew included copilot Lt. j.g. John W. Hanlon Jr. of Worcester, Mass.; Petty Officer Second Class Jack J. Parlier of Decatur, Ill.; Petty Officer Second Class Donald Graham Lewallen of Omaha, Neb.; Petty Officer Second Class Clarence Crome Fridley of Manhattan, Kan.; Petty Officer Third Class Samuel Leslie Crown Jr. of Columbus, Ohio; and Petty Officer Third Class James Stephen Palko of Superior, Wis.

More than 78,000 servicemen are missing in action from World War II, military officials said yesterday.

20 November 2003

World War Two fliers found in Russia buried in U.S.

Seven U.S. Navy airmen missing since World War Two aboard a bomber later found in Russia were buried on Thursday at Arlington National Cemetery, overlooking Washington.

The wreckage of their PV-1 Ventura bomber was found in 1962 on the Kamchatka Peninsula on Russia’s far eastern border. Subsequent searches and scientific tests confirmed the identities of the seven men.

The seven, buried with honors in a group ceremony, included Lt. Walter Whitman Jr. of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Lt. jg John Hanlon Jr. of Worcester, Massachusetts; Petty Officer 2nd Class Clarence Fridley of Manhattan, Montana, and Petty Officer 2nd Class Donald Lewallen of Omaha, Nebraska.

They also included Petty Officer 2nd Class Jack Parlier of Decatur, Illinois; Petty Officer 3rd Class Samuel Crown Jr. of Columbus, Ohio, and Petty Officer 3rd Class James Palko of Superior, Wisconsin.

On March 25, 1944, Whitman and his crew took off in their PV-1 as part of a five-plane flight from their base on Attu Island, Alaska, headed for enemy targets in the Kurile Islands of Japan.

The flight encountered heavy weather throughout the trip. About six hours into the mission, the base at Attu notified Whitman by radio of his bearing.

But there was no further contact with the crew and, when Whitman’s aircraft failed to return, a search was initiated by surface ships and aircraft in an area extending 200 miles (322 km) from Attu. No wreckage was found.

In January 2000, representatives of the U.S.-Russia Joint Commission on POW/MIAs received a report from a Russian citizen who had discovered wreckage in 1962 of a U.S. aircraft on the Kamchatka peninsula.

Later that year, specialists from the U.S. military’s Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii along with members of the commission found the wreckage and some human remains.

In 2001, the team returned to the site to conduct an excavation. They recovered additional remains, artifacts and aircrew-related items, which correlated to the names on the manifest of the PV-1.

Between 2001 and this year, scientists used a range of forensic identification techniques, including of mitochondrial DNA, to confirm the crewmembers’ identities.

More than 78,000 servicemen remain missing in action from World War II.

World War II soldiers’ remains buried at Arlington

Thursday, November 20, 2003

The remains of seven servicemen whose plane crashed in Russia after taking off from Alaska during World War II were buried Thursday in Arlington National Cemetery.

The group burial was conducted with full military honors, the Defense Department said in a news release.

The servicemen were aboard a Navy bomber that left Attu Island in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands on March 25, 1944, and headed for enemy targets in the Kurile Island of Japan.

The PV-1 Ventura bomber was part of a five-plane flight that encountered bad weather during the mission. The plane failed to return to its base, and a search found nothing.

The Defense Department identified the seven as Lieutenant Walter S. Whitman Jr. of Philadelphia; Lieutenant (jg) John W. Hanlon Jr. of Worcester, Mass.; Petty Officer 2nd Class Clarence C. Fridley of Manhattan, Montana; Petty Officer 2nd Class Donald G. Lewallen of Omaha, Nebraska; Petty Officer 2nd Class Jack J. Parlier of Decatur, Illinois; Petty Officer 3rd Class Samuel L. Crown Jr. of Columbus, Ohio; and Petty Officer 3rd Class James S. Palko of Superior, Wisconsin.

In January 2000, representatives of a U.S.-Russia joint commission of prisoners of war and soldiers missing in action received a report about a Russian citizen who had found wreckage of a U.S. aircraft on the Kamchatka Peninsula in 1962. The peninsula is on the east coast of Russia.

Specialists from the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii, along with members of the commission, went to the site and found wreckage and some human remains. The team returned to excavate the site in 2001. Additional remains were recovered, along with other items belonging to the crew.

Scientists at the lab used techniques including DNA analysis to confirm that the remains were those of the World War II crew.

From a contemporary press report: 17 November 2003

WW II mission `finally over’

7 men to be honored 59 years after plane crashed in Siberia

Jack Parlier’s first and only bombing mission began March 25, 1944, when the 22-year-old Navy meteorologist from Mt. Sterling, Illinois, took off with six crewmates from Attu Island in Alaska.

The plan was to bomb a target on the Kurile Islands in Japan and head back to Attu, near the western edge of the Aleutian Islands. But the bomber never returned.

“For over 50 years, we really didn’t know what happened,” said Boris Georgeff, 86, of Northbrook, who belonged to Parlier’s unit and helped look for the missing plane in 1944.

This week, remains of the crew–found years later at a crash site in Siberia–will be laid to rest with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.

“I know I will feel it’s finally over,” said Charlotte Davis, Parlier’s older sister, who lives on Chicago’s Near North Side.

For family and comrades of the men who were lost, the ceremonies Wednesday and Thursday will close the book on a decades-old mystery of what happened to the bomber. A crucial piece of the puzzle emerged only after the Cold War, when relations between the United States and Russia improved: The plane went down on the Kamchatka Peninsula in Siberia.

By the time a U.S. expedition arrived at the crash site in 2001, the only remains were small pieces of bone. But it was enough to identify three members of Parlier’s crew. Nobody knows what happened to the other four.

Few personal effects were recovered at the site, but the search team found a 1943 nickel. It will go to Davis after the ceremony, officials said.

“I’ve been told that he flipped a nickel with another meteorologist to see who would go on the bombing run, or a less dangerous reconnaissance flight,” Davis said. “He lost the flip.”

The wind was fierce and the snow heavy when Bomber 31 flew its last mission.

The Ventura PV-1 bomber was among five planes that took off from Attu–all of them from Unit 139 of Fleet Air Wing 4 of the U.S. Navy. The nighttime bombing runs were known as the “Empire Express,” and the men who flew them were known as “bats.”

Parlier was the aerographer, a meteorologist who also took pictures of weather systems. The rest of the crew were navigator Don LeWallen of Omaha; gunner Jimmy Palko of Superior, Wis.; shipboard mechanic Clarence Fridley of Manhattan, Mont.; pilot Walt Whitman of Philadelphia; co-pilot Jack Hanlon of Worcester, Mass.; and radio operator Sammy Crown Jr. of Columbus, Ohio.

Lieutenant Whitman, known as one of the most highly skilled pilots in his unit, was at the controls as the bomber followed the other four into the sky, Georgeff said.

“One of the theories was that because Whitman was the last one over the target, that the earlier planes might have alerted the Japanese,” he said.

Whatever the reason, the bomber never came back. Georgeff was among those who participated in searches during the next week.

Pilots were taught that if they were in trouble anywhere near the Russian coast, they should head toward a small air strip on Kamchatka, but that area wasn’t searched in the week after the plane went missing because it was Soviet territory, Georgeff said.

Two years later, the U.S. government declared Parlier and the rest of his crew missing in action and presumed dead.

In 1962, a Russian geologist made a discovery that would become known to U.S. officials decades later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. While mapping an old volcano on Kamchatka, the geologist stumbled across a wrecked aircraft on the side of the mountain. It had crash-landed, but most of the plane was intact.

It wasn’t until 37 years later, after the U.S. and Russia had created a joint POW/MIA commission, that a Russian historian informed the United States of the 1962 find.

In 2001, a team of forensic investigators traveled to the crash site. They discovered the plane had taken fire, although they couldn’t tell if that’s why it crashed.

The team recovered whatever they could. After nearly six decades, there wasn’t much, but enough to confirm–with DNA samples from family members–that LeWallen, Palko and Fridley were among the dead, said Ken Terry, head of the POW/MIA section for Navy Casualty, a division of the U.S. Navy.

Investigators were unable to match any of the rest of the remains with the other four.

A portion of the remains will be laid to rest Thursday to symbolize the entire crew. Palko’s family requested that his remains be buried with those.

LeWallen’s family requested that he be interred separately at Arlington, and the ceremony for him is Wednesday. Fridley’s family buried his remains on Veterans Day in a cemetery in Eureka, Calif., near where they live.

Not all the survivors will attend the ceremonies in Arlington. Davis’ younger sister, Phyllis Thompson, said the burials will not remove the lingering pain of losing her brother.

Parlier had been attending the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for two years when he joined the Navy in 1942, and he seemed to have a bright future, his sisters said.

“After all those years, I really had my doubts about what would be found,” Thompson said. “And now I guess this is the last we’ll ever know.”

World War II mission `finally over:

Samuel L. Crown, Jr.

- Aviation Radioman, Third Class, U.S. Navy

- 06125394

- United States Naval Reserve

- Entered the Service from: Ohio

- Died: January 16, 1946

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memorial

- Honolulu, Hawaii

- Awards: Purple Heart

- Aviation Machinist’s Mate, Second Class, U.S. Navy

- 03775592

- United States Naval Reserve

- Entered the Service from: California

- Died: January 16, 1946

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memorial

- Honolulu, Hawaii

- Awards: Purple Heart

- Lieutenant Junior Grade, U.S. Navy

- 0-145441

- United States Naval Reserve

- Entered the Service from: Massachusetts

- Died: January 16, 1946

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memoria

- Honolulu, Hawaii

- Awards: Purple Heart

- Aviation Metalsmith, Second Class, U.S. Navy

- 05636083

- United States Naval Reserve

- Entered the Service from: California

- Died: January 16, 1946

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memorial

- Honolulu, Hawaii

- Awards: Purple Heart

James S. Palko

- Aviation Ordnanceman, Third Class, U.S. Navy

- 03292467

- United States Navy

- Entered the Service from: Wisconsin

- Died: January 16, 1946

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memorial

- Honolulu, Hawaii

- Awards: Purple Heart

- Aerographer’s Mate, Second Class, U.S. Navy

- 06693889

- United States Naval Reserve

- Entered the Service from: Illinois

- Died: January 16, 1946

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memorial

- Honolulu, Hawaii

- Awards: Purple Heart

Walter S. Whitman

- Lieutenant, U.S. Navy

- 0-106381

- United States Naval Reserve

- Entered the Service from: Florida

- Died: January 16, 1946

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memorial

- Honolulu, Hawaii

- Awards: Purple Heart

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard