From contemporary press reports

September 2, 1992: QUEENS LAKE, VIRGINIA

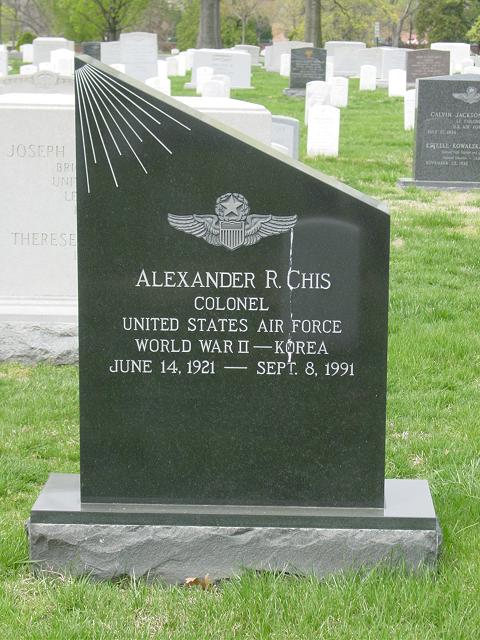

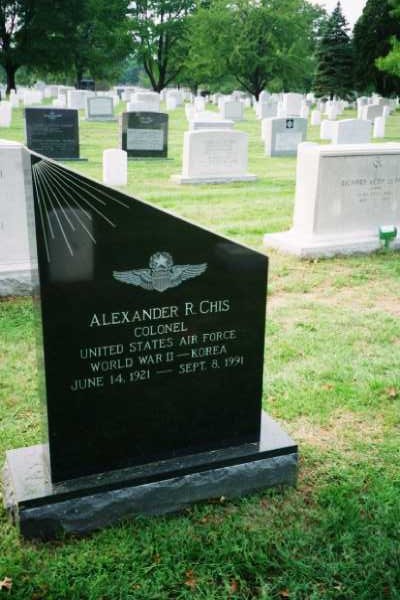

The first three times she visited her husband’s grave in Arlington National Cemetery, Genevieve (Gene) Chis had trouble finding it. Only a small plastic sign has marked the resting place of Alexander Chis for a year. The marker for grave 468-2 off McKinley Drive is hidden among large, personalized headstones in the southwest corner of the military cemetery. Now Chis is trying to get a unique, individual marker — an angled, black headstone — for her husband, a 20-year veteran of the Air Force. But in February, Arlington Superintendent John Metzler said no.

Taking up her cause, Representative Herbert Bateman, R- Virginia, recently asked Secretary of the Army Michael Stone to reverse the decision.

“We had none of this planned. Al died very suddenly,” Chis, 67, said recently. ” The monument at that point was secondary. The reason for burying him up there was not to build a private monument. It was to bury Al in a nicer place.”

Explaining the design rejection, Metzler said: “The one she designed was a one of a kind. There has to be some conformity, or we’d be back to the 1860s, where anything went: any design, any shape.”

When Arlington National Cemetery opened during the Civil War, it was divided into two sections. One was for regulation headstones and another was reserved for those veterans — usually officers — who could afford to pay for their own tombstones. The legacy of that section, where Alexander Chis is buried, includes tombstones in the shape of boulders, equestrian statues and free-standing crosses. Metzler told Chis in March that he rejected her design because of its angled top. Chis said it meets the regulations she was given when her husband died in September: that headstones be “of simple design, dignified and appropriate to a military cemetery.”

Alexander Chis’ marker would be black granite from Africa, to give a sense of the night flights he made to Alaskan radar outposts during the dark Arctic winter. The family wants nine rays cut into the stone to represent those left behind: Genevieve Chis, her children and her grand-children, who helped design the marker. And the top of the memorial would be a simple angle. That reminds Genevieve Chis of all the photos her husband took from his plane with a slice of wing often visible at the edge.

Metzler got support for his decision by asking Charles Atherton, Secretary of the Commission of Fine Arts, to comment on Chis’ design. It was the first time in 30 years the commission was consulted on such a decision, Atherton said. Atherton said his main reason for rejecting the design was that it was unlike the simple regulation headstones in the government-maintained sections.

To bolster her case, Chis went to Arlington in July to photograph unusual headstones. She found two unusual markers from 1988, one with a full-color photo on the front and another with a cross jutting upward out of the stone. “Mine is as simple as any of these. It’s just got that angle,” she said.

July 16, 1992:

Alexander Chis lies on a hill of such sweet peace. He’s in the shadow of a pin oak in Section 11, far from the madding crowds elsewhere in Arlington National Cemetery. The only sounds around him one recent morning were a rustling breeze and, faintly, taps, announcing a newcomer. Al Chis was a pilot. He flew 50 recon missions over Europe in the big war of his generation and then he did the small one in Korea. Al was Air Force for 26 years, rising to full Colonel before retiring in 1965, and he had always told Genevieve to put him in Arlington when it was time. It was time on September 8, 1991. Al had watched a football game on TV at home in Williamsburg. He stood up and he fell dead. He had lived 70 good years.

That night, the funeral director told Genevieve (Gene) that she could have Al buried in a section of Arlington where larger, more personal tombstones are permitted. Gene was surprised. Arlington, she had always thought, was row- upon-row of identical, white, government-bought headstones. But, in fact, there are areas where anyone, of any rank, can be buried under his own marker, if the family pays for and maintains it. The funeral director said such areas are often nicer. They have more trees, like Section 11.

Gene liked that. She wanted Al there. She would be there too when her time came. Now began a work of family love. They buried Al under a small temporary sign, and for the next four months Gene, who is 67, and her 4 grown kids and 4 grandchildren thought about the headstone. It had to represent so much. The cemetery had given them rules about size and inscription, and said the headstone had to be “of simple design, dignified and appropriate to a military cemetery.” Four times they drove from Williamsburg to search the cemetery for ideas. They talked, they sketched. And at last decided. It would be jet-black granite. It would have Al’s name, rank and wars. It would have his command pilot’s wings engraved above his name, and on the back would be Very Best Husband, Dad, Grandpa. But the most distinctive feature would be the shape. The top would be a diagonal, slanting from upper left to a point two-thirds as high on the right, creating a trapezoid instead of a rectangle. That diagonal cut was everything to Gene. It said Al. It said her. Al liked to dabble in sculpture and she’s a floral designer, and having a headstone that was nothing but uniform-side to side and top to bottom-would have been so unimaginative. She’s not the type, she says, to evenly space things on a mantel, for example. “I’ve just always been asymmetrical in everything I’ve done,” Gene says.

Because the upper left corner would form a triangle, they realized they could create a sun effect, as if the corner was the sun and rays were emanating from it. They wanted nine rays, one for Gene and one for each kid and grandkid, shining down toward Al’s name, forever. The headstone would cost $4,650. “We thought it was beautiful,” Gene says.

John C. Metzler didn’t want it, for the very reason the family did. “It was a unique design,” says Metzler, Arlington Superintendent. He wants traditional shapes. So does Charles H. Atherton, Secretary of the Commission of Fine Arts, who says the diagonal would disrupt the “great uniformity and sense of cohesiveness” unique to a military cemetery.

“There’s a tradition of military cemeteries to suppress individuality and emphasize unity,” Atherton says. ” That’s a great statement about the military: You’re all in it together, from Private to General, white, black, Christian, Jew.” If unusual shapes are allowed, Atherton says, “I don’t know where you stop.” Nowhere, though, did the rules given to Gene discuss shape. They just said simple, dignified, appropriate. It was only after rejecting the Chis design that the cemetery provided Gene with suggested designs. If she had had them beforehand, Gene says, she would have picked one. But the family went through so much work and followed the rules exactly as they had them and even had found at Arlington a similarly cut headstone. “I think mine is simple and dignified,” Gene says. “What do you think?”

I agree. It is not ornate. It is elegant. “I don’t know how anybody could say the stone is in bad taste,” says Peter Molina, of Apperson & Dent of Alexandria, the firm that was going to make it. Gene says uniformity already is undercut by the sections for private headstones, markers that vary widely in size, if not shape. And there are many ostentatious headstones from earlier eras, obelisks and what not. She appealed, but lost. She worries she’s not being a good military wife, that she’s refusing an order. “He was never a troublemaker,” Gene says, “and I sometimes have nightmares about whether Al would approve of me continuing this fight.”

She believes she’ll have to give in. Even so, “Any other design but this one won’t feel right. We put our heart and soul into this design, we really did.” So, ten months after his death, Al Chis lies on a hill of such sweet peace, unmarked by his family’s tribute.

September 6, 1992:

A Williamsburg woman said yesterday (September 5, 1992) that she has won an appeal to put a unique headstone on her husband’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery.

Army Secretary Michael P. W. Stone reversed a decision by Cemetery Superintendent John C. Metzler, who had said a trapezoidal, black granite tombstone was too unconventional for a military cemetery.

Genevieve Chis, 67, had requested the marker for the grave of her husband, Alexander Chis, 70, a retired Air Force pilot who died a year ago this Tuesday.

“The lesson learned is, if you really believe you’re right and it means a lot to you, you should pursue it as far as you can,” said Chis, who learned of Stone’s decision Friday from Representative Herbert Bateman (R- Va.).

Although much of Arlington Cemetery consists of identical white headstones, there are areas where any veteran may be buried under the family’s own marker, provided the family pays for it. Chis and her family, which includes four children and four grandchildren, had proposed a four-sided headstone, only two sides of which would be parallel. The triangle resulting at the top left corner of the marker would create the effect of having the sun in the corner and nine rays representing each family member.

Metzler and Charles H. Atherton, Secretary of the Commission of Fine Arts, believed the marker should conform to the rules for a “simple design, dignified and appropriate to a military cemetery.” Chis said she believes the design fit the rules.

Atherton said yesterday: “Obviously, if the Secretary of the Army did this, he did it for all the wrong reasons.” He said that the Chis family’s design was “not all that outrageous,” but that the tradition at Arlington is to subdue individual expression “to feel a common bond with your fellow military personnel.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard