From a contemporary news reports:

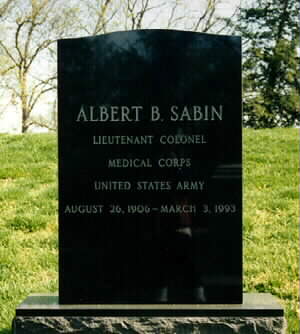

A legend of modern medicine and local resident for many years, died at Georgetown University Medical Center, March 4, 1993. Buried Monday March 8, 1993. He was 86.

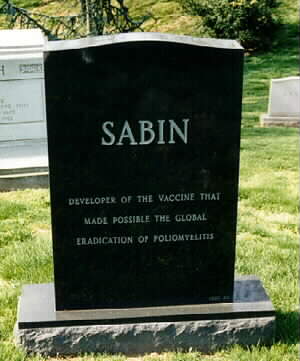

His oral polio vaccine saved millions from crippling disease or death, and he now rests in Section 3 in Arlington National Cemetery, near Dr Walter Reed, whose work in Panama conquered Yellow Fever. He also worked in the Army, although his breakthrough work on polio came later.

It is estimated that during past 21 years his vaccine has prevented about 5 million cases of paralytic polio and 500,000 deaths. Polio-myelitis, technical name of the disease, is also known as infantile paralysis, as most of its victims were children.

Born 1906 in Bialystok, Poland, he emigrated to the US, speaking no English. He learned enough to finish high school in New York City, then went on to undergraduate and medical studies at New York University. He worked in polio research at Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research until the outbreak of World War II. At that time, he joined US Army where between 1943-46 served with Board of Investigation of Epidemic Diseases of Office of the Surgeon General, with special missions in the Middle East, Africa, Sicily, Okinawa and the Philippines. He isolated viruses for sand fly fever, found a vaccine for dengue fever and developed vaccine against Japanese encephalitis.

He returned to polio research after war, continuing a 30-year association with the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. He developed his vaccine by the mid 1950s. At the time, disease was one of the most feared, becoming highly contagious during summer months. In 1952 there were 21,000 reported cases, many requiring artificial breathing aid of so-called “iron lung.” It has virtually disappeared since mass immunizations began in early 1960s with his live-virus vaccine, which was administered orally, on lump of sugar.

Jonas Salk had already produced an injectable vaccine, and the two became rivals. Salk described his rival’s death to a Washington Post staff writer as “a great loss. His contribution toward the control of polio will endure long into the future.”

During 1970 served successively as president of the Weizmann Institute of Science, and full-time expert consultant to National Cancer Institute in 1974. Then he became distinguished research professor of biomedicine at the Medical University of South Carolina from 1974 to 1982, and senior expert consultant at Fogarty International Center for Advanced Studies in Health Sciences of National Institutes of Health from 1984 to 1986.

Since his 80th birthday, has worked part-time at Fogarty International Center as senior medical science advisor and as a lecturer in US and abroad. He was a member of National Academy of Sciences, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Association of American Physicians, the American Pediatric Society and many other professional societies throughout the world. He also has served as a member of many advisory committees on medical research, including panels advising National Institutes of Health, US Armed Forces, World Health Organization, and the Pan American Health Organization.

He received more than 40 honorary degrees from US and foreign universities and is recipient of numerous awards including US National Medal of Science, Presidential Medal of Freedom, Medal of Liberty and Order of Friendship Among Peoples, awarded by Presidium of Supreme Soviet of the USSR. When the National Medal of Science was presented to him in 1971 by the President of US, the citation reads: “For numerous fundamental contributions to the understanding of viruses and viral diseases, in development of the vaccine which has eliminated poliomyelitis as major threat to human health.”

Dr. Albert B. Sabin, the pioneering researcher on viruses and viral diseases who developed the vaccine that is the main defense against polio in the United States and much of the rest of the world, died yesterday at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington. He was 86 years old and lived in Washington.

The cause of death was congestive heart failure, the hospital said.

He was best known for developing the live-virus polio vaccine, taken orally. It became generally preferred over the alternative killed-virus vaccine developed by Dr. Jonas Salk after a sometimes intense clash between the rival camps and their principals.

Although the Salk polio vaccine, which is injected, proved to be effective in sharply reducing the number of poliomyelitis cases in the United States, after it went on the market in 1955, Dr. Sabin persisted in his efforts to develop a vaccine based on a living virus, which he believed would be superior.

Dr. Sabin’s vaccine, which contained harmless, or attenuated, polio viruses, was developed by him and his co-workers at the University of Cincinnati. Before coming into wide use in this country, the vaccine was tested in millions of people in 1958 and 1959 in the Soviet Union, where it proved widely successful. In the United States the vaccine was tested earlier on prisoners who volunteered for the experiments and before that on Dr. Sabin himself and members of his family.

Its virtues, including delivery in syrup or a sugar cube instead of by injection, became accepted in the United States after the testing abroad. It was licensed in 1961 and eventually became the vaccine of choice in most parts of the world, although a few countries still use the Salk-type vaccines.

The Sabin vaccine received a temporary setback when public health officials reported that a few children, about one in a million inoculated, were developing polio because of the virus. Dr. Sabin, however, never admitted that his vaccine was responsible.

“He was so strong-willed he thought he could will it away,” Dr. Joseph L. Melnick of the Baylor College of Medicine at Houston said yesterday from Geneva. Dr. Melnick described Dr. Sabin as “one of the world’s greatest virologists.”

For Governments, A Straight-Talker

The development of the Sabin polio vaccine was the culmination of 20 years of research on the nature, transmission and epidemiology of the three closely related virus types that cause poliomyelitis, which was more frequently called infantile paralysis when Dr. Sabin was a young scientist. The disease was a dreaded cause of paralysis and death, especially in young people.

Dr. Sabin also was an adviser to the governments of the United States and other nations on important health issues.

A scholarly looking man whose hair turned white in middle age, he continued a full working and traveling schedule into his 70’s.

Scientists who knew Dr. Sabin well said he was eloquent and extremely difficult to defeat in a scientific argument. These talents apparently persisted all his life, as did a tendency to speak the truth as he saw it without diplomatic considerations.

In the swine flu episode of 1976, when the Federal Government feared an epidemic, he first supported but later denounced the Federal policy of vaccinating all adults against the flu virus, which bore a strong chemical resemblance to the virus that had caused the disastrous pandemic of 1918-1919.

Dr. Sabin made Federal officials unhappy by saying he doubted there was as much danger from the swine flu as the public was being led to believe. He argued that the vaccination campaign should await evidence that the virus was indeed reappearing in the population. As it turned out, the feared epidemic never did materialize and vaccination was followed by serious illness in several hundred people.

In 1980, at the age of 74, Dr. Sabin went to Brazil to help that country cope with polio outbreaks but soon found government doors closed to him because of his outspokenness.

In particular, he said the Brazilian Government had falsified data in the early 1970’s to give the World Health Organization, a United Nations agency, a falsely optimistic picture of polio eradication in that country. He estimated that in 1980 there was 10 times as much polio in Brazil as was being reported and that efficient vaccination efforts were being blocked by bureaucratic interference. Soon thereafter he was told by the Brazilian Government that his advice was no longer needed.

In the early years of his research on the polio virus, Dr. Sabin was credited with the first demonstration that it could grow in human nerve tissue outside the human body. Through research on monkeys he developed a method for determining how the polio virus entered the human body.

It had been widely thought that the polio virus entered the victims through the nose to the respiratory system. But Dr. Sabin proved that the virus first invaded the digestive tract and later attacked nerve tissue. He was also among the scientists who identified the three types of polio virus.

After Poland, A Quick Transition

Albert Bruce Sabin was born Aug. 26, 1906, in Bialystok, Poland, then a part of Imperial Russia. He and his family immigrated to the United States in 1921, at least partly to escape the persecution of Jews. He attended high school in Paterson, N.J., after taking a six-week cram course in English from two cousins.

After graduation from high school he first planned a career in dentistry because an uncle, a dentist, offered to finance his college education if he would enter that profession. Dr. Sabin said years afterward that he studied dentistry for three years and then “couldn’t stand it any longer” because he had become captivated by the possibilities of medical research.

He graduated from New York University in 1928. With the aid of scholarships, fellowships and odd jobs, he attended the university’s medical school and, while there, found time to do research on pneumococcus bacterial infections.

He was awarded an M.D. degree in 1931. That summer, a polio epidemic in New York influenced his choice of a research career on polio and other infectious diseases of the human nervous system.

Before entering full-time research in that field, however, he trained in pathology, surgery and internal medicine at Bellevue Hospital, through 1933. He spent the next year in research at the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine in London.

In 1935 he returned to New York to join the research staff of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, now Rockefeller University.

In 1939 Dr. Sabin moved to the University of Cincinnati and its Children’s Hospital Research Foundation to conduct research on viruses.

Wide Research As Army Officer

After the United States entered World War II, Dr. Sabin became a consultant to the Army on viral diseases. Later, as a lieutenant colonel in the Medical Corps, he studied diseases affecting American troops throughout the world.

He isolated the virus that caused sandfly fever, a nonfatal epidemic disease that was causing illness among troops in Africa. Later he showed that an ordinary mosquito repellent would provide protection against the infection by warding off the insects that carried the disease.

He helped develop a vaccine against dengue fever, a debilitating but usually nonfatal disease that was striking many troops in the South Pacific. He also studied the parasites that cause toxoplasmosis, as well as the viruses that cause encephalitis, inflammations of brain tissue.

Late in World War II, a vaccine he had developed against Japanese encephalitis virus was given to about 70,000 American troops preparing for the invasion of Japan. A decade after the war, Dr. Sabin was the first to identify a virus called echo 9 as a cause of human intestinal illness.

At the end of the war, Dr. Sabin returned to the University of Cincinnati to continue work on polio. He developed a live-virus vaccine that was first tested in 1954. By that time, however, the killed-virus polio vaccine developed by Dr. Salk had already been developed, tested and was being put into use.

Public health experts in the United States decided the Sabin vaccine should be given its first major trials abroad, so that people already protected by the Salk vaccine could not be accidentally included in the studies and thus confuse the results.

In this country, the Sabin vaccine was first used on a large scale in 1960 in Cincinnati, where it was given to 180,000 schoolchildren.

Two years later all three constituents of the vaccine, one against each of the three major polio virus types, were licensed by the United States Public Health Service.

Whereas the Salk vaccine had to be given by injection and required later booster shots to insure long-term immunity, the Sabin live-virus vaccine could be taken by mouth and provided lifetime protection against polio. Moreover, the harmless virus of the vaccine seemed to be “catching”: It spread beyond the recipients to protect even some people who had not received the vaccine at all.

From Bitter Rival, A Word of Praise

Although the Salk vaccine continued to have adherents, the Sabin vaccine replaced it as the prime defense against polio in this country. A sharp rivalry between Dr. Salk and Dr. Sabin persisted thereafter.

Asked about the Salk vaccine at the age of 84, Dr. Sabin declared the killed-virus preparation to be “pure kitchen chemistry.”

“Salk didn’t discover anything,” he said.

Dr. Salk, for his part, attributed such comments to professional jealousy. “Albert Sabin was out for me from the very beginning,” he said. “I remember in Copenhagen in 1960, he said to me, just like that, that he was out to kill the killed vaccine.”

But Dr. Salk issued a statement yesterday praising Dr. Sabin’s enduring contributions to the control of polio.

In 1970 Dr. Sabin became president of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel but stepped down in November 1972 because of a heart condition for which he had open heart surgery.

In the latter part of his career, Dr. Sabin’s interest in viruses led him into research on the relationships between human cancer and viruses. Although he thought at one time that he and co-workers had discovered a virus that caused several types of human cancer, he later concluded that the virus in question was not a factor in human malignant disease.

Dr. Sabin was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1951 and received numerous other honors, including the Bruce Memorial Award of the American College of Physicians in 1961, the Feltinelli Prize of the Accademia dei Lincei of Rome in 1964, the Lasker Clinical Science Award in 1965 and the United States National Medal of Science in 1971.

Throughout his long career he was noted for diligence, hard work and long hours as well as brilliance in research.

“A scientist who is also a human being cannot rest while knowledge which might be used to reduce suffering rests on the shelf,” he once said.

Dr. Sabin was married to Sylvia Tregillus in 1935; she died in 1966. He married Jane Warner, but the marriage ended in divorce. In 1972, he married Heloisa Dunshee de Abranches.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by two daughters from his first marriage, Deborah Sabin of Yakima, Washington, and Amy Horn of Palo Alto, California, and three grandchildren.

What child of the 1950s and 1960s could not be grateful to Dr. Sabin for his work on our behalf. — MRP

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard