William P. Rogers, a suave and well-connected Republican lawyer who was secretary of state under President Richard M. Nixon and attorney general in the Eisenhower administration, died on Tuesday (January 2, 2001) in Bethesda, Maryland. He was 87.

Mr. Rogers lived in Bethesda and worked in the Washington office of the law firm of Clifford Chance Rogers & Wells, where he was senior partner, until becoming ill several months ago. He suffered from congestive heart failure, his family said.

Secretary of state from 1969 to 1973, Mr. Rogers left the Nixon administration unblemished by the Watergate scandals. But he was burdened by another shadow, that of Henry A. Kissinger. As Mr. Nixon’s chief national security adviser, Mr. Kissinger all but supplanted Mr. Rogers. And when Mr. Rogers departed, Mr. Kissinger became secretary of state in name as well. Mr. Rogers and Mr. Nixon had been close for years. There was speculation when Mr. Rogers became secretary of state that he would be a personal confidant of the president rather than a force in diplomacy. The conjecture was heightened because Mr. Nixon had strong ideas about America’s place in the world. Moreover, Mr. Rogers, while a distinguished lawyer, was not steeped in foreign policy, even though he had served on two United Nations panels, one that explored prison conditions around the world in 1955 and another that studied problems in Africa in 1967.

As it turned out, the eclipse of Mr. Rogers at the State Department was all but total. While he was involved in early discussions about United States policy toward China, it was Mr. Kissinger who secretly went to Beijing to arrange details of Mr. Nixon’s groundbreaking trip to China. It was widely reported that Mr. Rogers knew nothing of Mr. Kissinger’s mission and nothing of his secret negotiations with North Vietnam.

The two men had clashed in 1969, when Mr. Rogers said in a speech in New York that the American policy of withdrawal from Vietnam was “irreversible.” Mr. Kissinger tried to have the word stricken from the speech, on ground that it would give the North Vietnamese too much knowledge of American intentions, but Mr. Rogers prevailed.

Early in his first term, President Nixon rejected a suggestion from Mr. Rogers that the United States propose an immediate cease-fire in Vietnam. In 1970, the president widened the fighting into Cambodia and Laos, despite Mr. Rogers’s reservations.

Frozen out of policy-making on Southeast Asia, Mr. Rogers concentrated on the Middle East, but he was no more successful at achieving a lasting peace than other diplomats have been over the years.

Early in his second term, Mr. Nixon sent his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, to invite Mr. Rogers to resign. Mr. Haldeman recalled in his diary that Mr. Rogers was shocked and hurt but soon complied.

After Mr. Nixon’s death in 1994, Mr. Rogers praised him as “a great world leader,” one whose accomplishments “were overshadowed by another event that was deemed more newsworthy at the time.”

Mr. Rogers predicted that memories of Watergate would fade and that Mr. Nixon would gain stature in death, just as he had overcome so much in life to reach the presidency.

“I don’t know of any other mortal who went through what Richard Nixon went through and by the end of his life had recovered as much as he had,” Mr. Rogers went on. “He never gave in.”

That Richard Nixon rose to the height of political power in the first place was due not just to his own perseverance but, in no small measure, to William Rogers.

The two men got to know each other in the late 1940’s when Mr. Rogers was a committee counsel on Capitol Hill and Mr. Nixon was a young member of the House of Representatives. They were the same age, had similar political beliefs and both were golfers. Like Mr. Nixon, Mr. Rogers did not come from wealth. The men became friends, even though Mr. Rogers was more extroverted.

When Mr. Nixon was going after suspected Communists in the late1940’s, he asked Mr. Rogers for advice: Should he believe Whittaker Chambers, who had accused a State Department official, Alger Hiss, of giving secret documents to the Communists?

Mr. Rogers had been a prosecutor under Thomas E. Dewey, New York City’s racket- hunting district attorney, from 1938 to 1942. Mr. Rogers analyzed what Mr. Chambers had said and told Mr. Nixon that the account was detailed enough to be credible. So Mr. Nixon persisted, helped to bring down Mr. Hiss in one of the most sensational cases of the century, and was elected to the Senate in 1950.

At the Republican National Convention in 1952, Mr. Rogers did his part to secure the nomination for Dwight D. Eisenhower by helping to persuade the credentials committee that Eisenhower delegates from Louisiana, Texas, Georgia and Florida, rather than those loyal to Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio, should be seated.

Chosen as the vice-presidential candidate, Mr. Nixon asked Mr. Rogers to accompany him on a Western campaign tour. And when word got out that some of Mr. Nixon’s backers in California had set up a private “slush fund” for him, Mr. Rogers helped to ward off the cries of Republicans who wanted Mr. Nixon to be dropped from the ticket.

Then Mr. Rogers helped his friend prepare an explanation for the whole affair. On television, Mr. Nixon sought to defuse the accusations against him, in part by mentioning a sweet black and white dog that a supporter had given his family, a dog his daughters loved so much that to return it would be unthinkable.

The dog was named Checkers. The “Checkers speech” was derided by Nixon haters as insincere and mawkish, but it worked. Reaction was so favorable that Mr. Nixon stayed on the ticket, and became vice president.

Mr. Rogers was named a deputy attorney general in the new administration. When Attorney General Herbert Brownell resigned in 1957, Mr. Rogers, 44, became his successor and served for the rest of the Eisenhower years. He played a principal role in drafting the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and in establishing the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department.

After leaving the Eisenhower administration, Mr. Rogers had a role in one of the most important First Amendment cases in American history. It arose from a libel suit brought by L. B. Sullivan, the city commissioner in charge of the police in Montgomery, Ala., against The New York Times and four black ministers over an advertisement in The Times seeking contributions to help the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The advertisement spoke of “a wave of terror” against black students, and it contained inaccuracies.

In 1964, the United States Supreme Court overturned a libel judgment that Mr. Sullivan had won in Alabama. In doing so, the court accepted the thrust of the arguments by the defendants’ lawyers (and by Mr. Rogers, who filed a friend of the court brief on behalf of The Washington Post), ruling that public officials could win damages only if they showed that a libelous statement had been made “with actual malice” or reckless disregard of the truth.

The Supreme Court’s decision was a landmark ruling, giving journalists wide protections in what they can write and say.

Mr. Rogers prospered as a lawyer, so much so that when he agreed to become Mr. Nixon’s secretary of state it was at great financial sacrifice, as well as at some personal cost, as it turned out.

William Pierce Rogers was born on June 23, 1913, in Norfolk in upstate New York. His father was an insurance agent. When he was 13, William Rogers’s mother died, and he went to live with his grandparents in Canton, N.Y. He graduated first in his high school class and won a scholarship to Colgate University, where he washed dishes and sold brushes door to door to earn extra money.

Soon after graduating from Cornell Law School, he was named an assistant district attorney by Mr. Dewey in New York City. Mr. Rogers joined the Navy in 1942 and served on the aircraft carrier Intrepid in the invasion of Okinawa. The ship was struck twice by Japanese suicide planes.

After the war, he rejoined the New York district attorney’s office, by then headed by Frank Hogan, and in 1947 he went to Washington to work on Capitol Hill.

Mr. Rogers is survived by his wife of 64 years, Adele, whom he met in law school; a daughter, Dale Marshall; three sons, Anthony of Boston, Jeffrey of Portland, Ore., and Douglas of Columbus, Ohio; 11 grandchildren; and 4 great-grandchildren.

Mr. Rogers returned to public service one last time, when he headed a special commission that investigated the 1986 explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, which killed seven astronauts and set back the country’s space program.

When President Ronald Reagan chose Mr. Rogers for the panel, it was reportedly with the hope that he would place little blame on the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Early on in the hearings, the space agency was reluctant to reveal what it had learned about the cause of the explosion, which occurred in unusually chilly weather.

One member of the commission, the physicist Richard Feynman, thought he knew. In a famous demonstration, he inserted a small rubber ring in a glass of ice water, squeezed it with a clamp and held it up to show that it had not sprung back into shape, as it would have if it were warm.

The rubber ring was of the kind used as a seal in the rocket booster, designed to prevent the escape of dangerous hot gases. The physicist had shown in a way that any layman could understand that the rings were vulnerable in cold weather.

Mr. Rogers had wanted orderly hearings, with no theatrics. In a lunch break after Mr. Feynman’s demonstration, Mr. Rogers turned to another commission member, the astronaut Neil Armstrong, and was heard to say, “That Feynman is becoming a real pain.”

But despite his annoyance, Mr. Rogers became convinced that the space agency had not been forthcoming about the cold- weather hazard, and he endorsed a sharply critical report.

As for former President Nixon, Mr. Rogers said in a 1997 interview that he still felt bad about what happened between them. “I never before had a friend who turned out to be not quite a friend,” he said.

Courtesy of the Washington Post

By J.Y. Smith

Thursday, January 4, 2001

William P. Rogers, 87, who served Republican presidents as attorney

general and secretary of state and capped a public career that spanned five decades by leading the investigation of the Challenger space shuttle disaster in 1986, died of congestive heart failure January 2, 2001 at Suburban Hospital.

Mr. Rogers, a former assistant prosecutor in New York and a Navy veteran

of World War II, had been the chief counsel of a Senate investigating committee, a delegate to the U.N. General Assembly in 1965 and a member of an ad hoc U.N. committee on Southwest Africa. A senior member of the Washington-New York legal establishment, he was a partner in the law firm of Rogers & Wells, which a year ago became Clifford Chance Rogers & Wells.

In the 1960s, Mr. Rogers argued successfully before the U.S. Supreme

Court in two leading cases on libel law and the First Amendment, New York Times v. Sullivan and The Associated Press v. Walker.

In 1973, he received the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian

honor.

Mr. Rogers served President Dwight D. Eisenhower as deputy attorney general from 1953 to 1957 and as attorney general from 1957 to 1961. From 1969 to 1973, he was secretary of state under President Richard M. Nixon. His tenure at the State Department was marked by a ferocious and losing struggle with Henry M. Kissinger, then Nixon’s national security adviser, for control of foreign policy.

When the Challenger blew up during takeoff on January 29, 1986, killing all seven astronauts aboard, President Ronald Reagan appointed Mr. Rogers the head of a commission to find out what had happened.

In the panel’s first working session, Mr. Rogers realized that management failures at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration were a principal part of the problem. To ensure the commission’s objectivity, he barred from the investigation all NASA officials who had had a part in the launch decision. As he said in an interview, “We changed from a review body to a working-level investigating body.”

The tragedy was traced to a failed O-ring seal. In its report, the commission called the disaster “an accident rooted in history” and concluded, “The NASA shuttle program had no focal point for flight safety.”

The report was considered a model of its kind and led to extensive changes in the space exploration program.

In his years at the Justice Department, Mr. Rogers engaged in such matters as the selection of federal judges, the protection of civil rights and the welfare of Hungarian refugees arriving in the United States after the anti-communist uprising in 1956. As the country’s top law enforcement officer, he launched an anti-crime campaign, and he pursued an aggressive antitrust policy, bringing suits against such companies as General Motors and Westinghouse. He was a frequent administration spokesman on Capitol Hill.

Some of his greatest contributions were in the field of civil rights. He was involved in the crisis in Little Rock in 1957, when Eisenhower sent the Army to enforce federal

court orders integrating Central High School, and he played an important role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, which guaranteed the right to vote. He established the Civil Rights Division in the Justice Department and made it one of the most dynamic parts of the government.

Nixon chose Mr. Rogers to be secretary of state because he wanted to keep foreign policy in his own and Kissinger’s hands. Mr. Rogers had almost no experience in foreign affairs, but Nixon valued him for his loyalty. The two had been friends since first coming to Washington in the late 1940s, Nixon as a freshman Republican congressman from California and Mr. Rogers as a Senate committee aide.

Mr. Rogers had encouraged Nixon to pursue Alger Hiss, a former State Department official who had become president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. In dramatic testimony in 1948, Whittaker Chambers, a former communist and espionage agent, said Hiss had spied for Moscow during his State Department years.

Hiss denied it, and many rallied to his cause. President Harry S. Truman dismissed the charges as a red herring, and Secretary of State Dean Acheson declared famously, “I will not turn my back on Alger Hiss.”

Nixon, an obscure newcomer to Washington, was up against enormously powerful forces. But Mr. Rogers urged him to proceed because he believed Chambers had information that could not have been made up. This advice was vindicated by events. In 1950, after two years of investigations, charges and denials, Hiss was convicted of perjury and sentenced to prison. The episode was a landmark of the early Cold War years, and it made Nixon’s national reputation. Nixon went on to win election to the Senate in 1950.

In the 1952 election campaign, when the existence of a secret political fund almost forced Nixon to resign as Eisenhower’s vice presidential running mate, Mr. Rogers helped him write the “Checkers” speech that saved his candidacy.

On Sept. 24, 1955, when Eisenhower had a heart attack, Nixon turned to Mr. Rogers. Desperate to avoid the news media, Nixon slipped out of his house in the Wesley Heights section of Northwest Washington and spent the night in the Rogers home in Bethesda. Meanwhile, Nixon’s wife, Pat, served coffee to reporters camped out at the Nixon home.

When Eisenhower had a stroke in 1957, Mr. Rogers again was at Nixon’s side.

In the 1960s, when Nixon and Mr. Rogers were practicing law in New York,

they remained close, although there was competition between them for clients.

It was with those things in mind that Nixon chose Mr. Rogers to be secretary of state. In his memoirs, he wrote, “I knew that I could trust him to work with me on the

most sensitive assignments in domestic as well as foreign policy.”

Nixon also called Mr. Rogers a “strong administrator” who could manage “the reluctant bureaucracy of the State Department.” Given Mr. Rogers’s ability to get along with Congress, Nixon also hoped he would be able to halt “the almost institutionalized enmity” that had grown up between the White House and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee under Sen. J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.), a leading critic of U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

In “The White House Years,” his memoir of the period, Kissinger quoted

Nixon as saying: “Rogers was one of the toughest, most cold-eyed, self-centered, and ambitious men he had ever met. As a negotiator he would give the Soviets fits. And ‘the little boys in the State Department’ had better be careful because Rogers would brook no nonsense.”

Kissinger added: “Few secretaries of state can have been selected because of their President’s confidence in their ignorance of foreign policy.”

Mr. Rogers summarized his own view of the United States and its place in the world in these terms: “I reject the chessboard theory that we lose countries or gain them.

What I favor for the U.S. is a more natural role, befitting our character and capacities. Unless we are ready to risk war or intrude recklessly in others’ affairs, we must recognize that some problems are beyond our capacity to solve.”

In the councils of the Nixon administration, he often urged restraint. He opposed the bombing of communist sanctuaries in Cambodia in 1969, for example, and he favored a quick end to the war in Southeast Asia. When North Korea shot down a Navy spy plane with 31 people aboard, Mr. Rogers joined Defense Secretary Melvin R. Laird in successfully opposing plans to bomb a North Korean airfield in retaliation.

But because Nixon was determined to keep all the threads of foreign policy in his and Kissinger’s hands, the secretary of state was kept in the dark about many of the

administration’s most important initiatives and was not always supported in his own initiatives.

In 1969, Mr. Rogers was not told that Nixon had been in contact with Ho Chi Minh until 48 hours before the president revealed it on television.

Again in 1969, when the secretary proposed a formula for peace for Israel and its neighbors, the White House promptly spread the word that “the Rogers Plan” was aptly named — that it was the secretary’s idea, not the administration’s. Similarly, after Mr. Rogers and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin had their first substantive meeting on Vietnam, the president had Kissinger tell Dobrynin the secretary had gone beyond Nixon’s position.

In 1971, Mr. Rogers was not kept informed of White House-Kremlin talks that led to a breakthrough on strategic arms limitations. He learned of Nixon’s historic opening to Communist China that year only when Kissinger was on his way to Beijing to clear

the way for Nixon’s own visit.

Mr. Rogers and Kissinger attempted to hold regular meetings to coordinate their work, but soon gave it up.

“Rogers was too proud, I intellectually too arrogant,” Kissinger wrote in “The White House Years.”

“And we were both too insecure to adopt a course which would have saved us much unneeded anguish.”

Disputes between the two men were frequent. Mr. Rogers refused to carry out directives with which he disagreed unless he got orders from Nixon in person. Nixon, who hated face-to-face disagreement, preferred to deal in memos. On the theory that the memos actually had been written by Kissinger, the secretary ignored them even when they bore Nixon’s signature.

For his part, Kissinger was furious that Mr. Rogers still had direct access to the Oval Office and often was Nixon’s dinner guest in his private quarters at the White House, a favor the national security adviser never received.

As details leaked out, the rivalry was widely discussed in the press, with Mr. Rogers receiving much criticism for not protecting the State Department’s turf. Sen. Stuart

Symington (Mo.), a prominent Democrat, referred to him as “the laughingstock of the cocktail circuit.”

However, Kissinger later wrote: “Rogers was in fact far abler than he was pictured; he had a shrewd analytical mind and outstanding common sense. But his perspective was tactical; as a lawyer he was trained to deal with issues as they arose ‘on their merits.’ My approach was strategic and geopolitical; I attempted to relate events to each other, to create incentives or pressures in one part of the world to influence events in another.

“Rogers was keenly attuned to requirements of particular negotiations. I wanted to accumulate nuances for a long-range strategy. Rogers was concerned with immediate reaction in the Congress and media, which was to some extent his responsibility as principal spokesman in foreign affairs. I was more worried about results some years down the road.”

In his memoirs, Nixon said: “Since I valued both men for their different views and qualities, I tried to keep out of the personal fireworks that usually accompanied anything in which they both were involved.

“Rogers felt that Kissinger was Machiavellian, deceitful, egotistical, arrogant, and insulting. Kissinger felt that Rogers was vain, uninformed, unable to keep a secret, and hopelessly dominated by the State Department bureaucracy. . . . Kissinger suggested repeatedly that he might have to resign unless Rogers was restrained or replaced.”

In “Nixon in Winter,” published four years after the former president’s death in 1994, Monica Crowley quoted Nixon as making what amounted to an apology to his old friend.

“I’ll tell you right now — the way I treated Rogers was terrible,” Nixon said. “I had Kissinger, and he and I kept so many things from Rogers, and that was inexcusable. I used Kissinger when I should have been using my secretary of state, and we had our reasons, but it wasn’t right. I didn’t even tell Rogers about the China thing until it was a done deal. I regret that because Rogers was smart and a good man.”

William Pierce Rogers was born in Norfolk, New York, on June 23, 1913. His father was Harrison A. Rogers, a bank director and paper mill executive. His mother was Myra Beswick Rogers. He attended Colgate University on a scholarship, graduating in 1934. He received his law degree in 1937 from Cornell University, where he was an editor of Cornell Law Quarterly and a member of the Order of the Coif.

In 1938, after a brief stint with a Wall Street law firm, he was hired by Thomas E. Dewey, the future New York governor, as an assistant district attorney for Dewey’s campaign against the gangsters of Murder Inc. He was one of 60 lawyers out of 6,000 applicants who were hired. Over the next four years, he handled 1,000 cases.

During World War II, Mr. Rogers served in the Navy and saw action aboard an aircraft carrier at Okinawa.

After the war, he returned to the district attorney’s office, but soon moved to Washington to join the staff of the Senate War Investigating Committee, which became the Senate Permanent Investigating Committee. He was chief counsel from 1947 to 1950. The committee exposed “five-percenters” who fixed federal contracts for private firms.

In 1950, Mr. Rogers went to New York and became a partner of Dwight, Royall, Harris, Koegel & Caskey, a forerunner of Clifford Chance Rogers & Wells. He joined the firm after the Eisenhower administration and again after his years at the State Department. In the 1960s, his clients included The Washington Post Co.

Mr. Rogers, a tall, affable figure, had a reputation for being practical and unflappable. Friends said he had both a sense of humor and a temper. Although he spent much of his career at or near the center of events, he was essentially a private person. After leaving government, he rarely gave interviews. Asked once if he ever intended to write a book, he replied: “I don’t like to live in the past. You have to stop everything to write an authoritative book. And besides, it’s hard to write interestingly without being critical of people.”

Mr. Rogers held honorary degrees from Duquesne University, Loyola University, Columbia University, St. Lawrence University, Washington-Jefferson University, Middlebury College, Clarkson College and Colgate University.

He lived in Bethesda. He was a member of the Metropolitan, Burning Tree and Chevy Chase clubs in the Washington area and the Recess, Racquet and Tennis and Sky clubs in New York.

Survivors include his wife, the former Adele Langston, whom he married in 1937, of Bethesda; a daughter, Dale Rogers Marshall of Norton, Mass.; three sons, Douglas, of Columbus, Ohio, Jeffrey, of Portland, Ore., and Anthony, of Newton, Mass.; 11 grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

Presidential Medal of Freedom

WILLIAM P. ROGERS

Awarded by President Richard M. Nixon

October 15, 1973

Prosecutor, Congressional investigator, and Cabinet leader under two Presidents, his brilliant career of public service has spanned more than a third of a century and touched all three branches of Government. As the 63rd Attorney General of the United States, he pioneered in the battle for equal rights. As the Nation’s 55th Secretary of State, he played an indispensable role in ending our longest war and in starting to build a new structure of peace. Through these efforts, the decency and integrity that are William Rogers’ personal stamp are now felt more strongly among all people and nations. No man could seek a greater monument.

ROGERS, WILLIAM P.

The partners, attorneys, and staff of Clifford Chance Rogers & Wells, honor the memory of our senior partner and dear friend, WILLIAM P. ROGERS. He was a statesman and mentor who embodied the highest standards of ethics and leadership, both to our nation and to our firm. He will be greatly missed. We extend our deep sympathy to his wife, Adele, and his family.

Clifford, Chance, Rogers & Wells, LLP

ROGERS, HON. WILLIAM P.

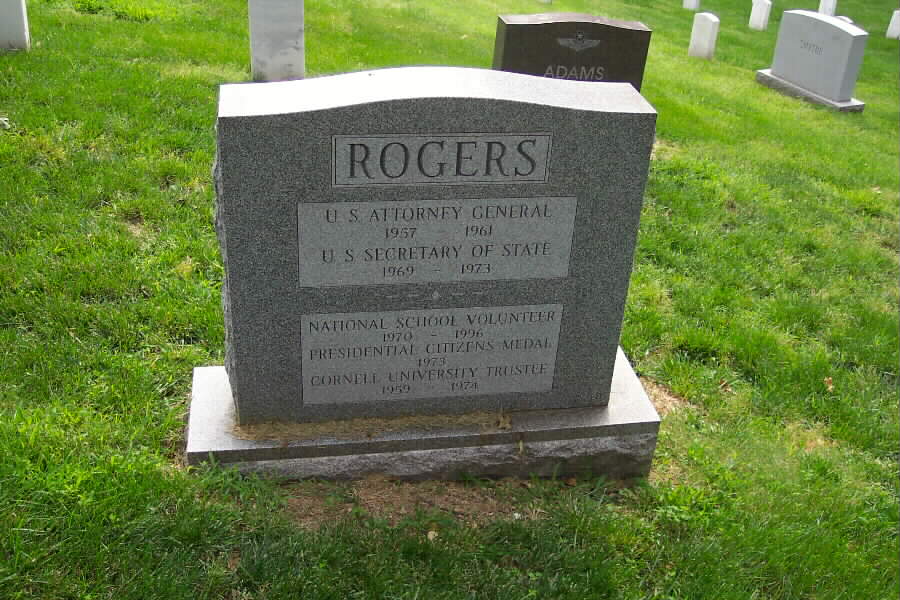

On January 2, 2001, Hon William P. Rogers of Bethesda, MD. Beloved husband of Adele Langston Rogers; father of Dale Rogers Marshall, Norton, MA, Anthony Wood Rogers, Newton, MA, Jeffrey Langston Rogers, Portland, OR and Douglas Langston Rogers, Columbus, OH. Also survived by eleven grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. Memorial services will be held at the National Presbyterian Church, 4101 Nebraska Ave, NW, Washington, DC on Monday, January 8, at 3:00 P.M. Private interment in Arlington National Cemetery. In lieu of flowers memorial contributions may be made to the American Foreign Service Association, Colgate University or Cornell University.

Secretary Rogers is buried in Section 30 of Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Adele Langston Rogers (15 August 1911-27 May 2001) is buried with him.

ROGERS, WILLIAM PIERCE

- LCDR US NAVY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 08/16/1942 – 01/26/1946

- DATE OF BIRTH: 06/23/1913

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/02/2001

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 01/09/2001

- BURIED AT: SECTION 30 SITE 817 LH

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

ROGERS, ADELE L

- DATE OF BIRTH: 08/15/1911

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/27/2001

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 06/01/2001

- BURIED AT: SECTION 30 SITE 817 LH

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

- WIFE OF ROGERS, WILLIAM P LCDR US NAVY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard