A career Army enlisted man at the outbreak of W.W.I, he received temporary commission. He was gassed during the war, but elected to stay in Army until 1923 when eligible for a complete pension. However, the Army would only let him stay on if he accepted a reduction from First Lieutenant to Sergeant, which he did. He also served briefly as a Major in World War II.

Dec 5, 1994: The list of Northern Kentuckians who have fought in our nation’s wars is long and distinguished. But the man claimed by most as our area’s greatest soldier was not a native. He was an adopted son from Indiana.

The soldier was Samuel Woodfill. Today Woodfill is probably best known as the namesake of Samuel Woodfill Elementary School at US 27 and South Ft Thomas Avenue in Ft Thomas. Apart from his military career, however, success often eluded Woodfill. He was proclaimed as America’s most outstanding soldier of World War I by no one less than General John “Black Jack” Pershing. Woodfill also was selected as part of the honor guard at the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C.

Despite those honors, Woodfill struggled to make a living as a civilian. An attempt at farming, for example, was unsuccessful. He made newspaper headlines at the time of his death but died alone on his farm in Indiana.

He was born in Jefferson County, Indiana, in January 1883. Accounts say his father, John H. Woodfill, was a veteran of the Mexican War and had served with the 5th Indiana Volunteers during the Civil War. Woodfill reportedly became a good shot by age 10 and often sneaked off to go hunting. He enlisted in the Army in 1901 and was sent to the Philippines. The United States had won control of the Philippines from Spain during the Spanish-American War. Before that war, some natives of the Philippines were already waging guerrilla warfare against the Spanish. The guerrillas supported the American troops, assuming the United States would grant them independence. The US won but did not grant the islands independence. That led to a prolonged guerrilla war against the U.S.

Later, Woodfill was stationed in Alaska during an American show of force when the US was involved in a border dispute with Canada and England over the Alaska-Yukon area. Woodfill apparently was stationed first in Fort Thomas in 1912 and 2 years later was among troops from Fort Thomas sent to the Mexican border in an attempt to protect Texas, New Mexico and Arizona from attacks by Mexican bandits. At the time Mexico was involved in a civil war. The troops, including Woodfill, eventually returned to Fort Thomas. While back in Fort Thomas, Woodfill met and on Christmas Day 1917 married Lorena Wiltshire. An account in 1942 said Mrs. Woodfill was a direct descendent of Daniel Boone. The Woodfills later owned a house at 1334 Alexandria Pike in Fort Thomas. The year he married, Woodfill was promoted to Lieutenant. That was the rank he held in April 1918 when he and others at Fort Thomas were dispatched to Europe. They were part of the American Expeditionary Force headed by General Pershing to fight in World War I.

Woodfill was a member of the Army’s 60th Infantry, Fifth Division, which was sent to the Meuse-Argonne front in France in the fall of 1918. The battle there began in September and lasted 45 days, costing thousands of lives on both sides.

Woodfill earned his place in American military history on the morning of October 12, 1918, near Cunel, France. While Woodfill and his men were attempting to move through a thick fog, German artillery and machine gun fire pinned them down. Followed by two of his men, Woodfill went about 25 yards ahead toward a German-held machine gun emplacement. Leaving his two men where they were, Woodfill moved alone, working his way around the end of the machine gun emplacement. The machine gun was firing, but Woodfill was not hit. When he was within about 10 yards of the Germans, the gun stopped firing and Woodfill could see three German soldiers. Woodfill shot all three. A fourth German in the gun pit – an officer – rushed Woodfill. In a hand-to-hand struggle, Woodfill killed the officer. Woodfill then ordered the rest of his patrol ahead, but they soon encountered another machine gun. Woodfill ordered a charge, shooting several of the Germans, capturing three others alive and silencing the machine gun. A few minutes later Woodfill and his men discovered another machine gun emplacement. Again Woodfill charged the emplacement, shooting and killing five German soldiers with rifle fire. He then drew his pistol and jumped into the machine gun pit. Unable to kill the enemy with his pistol, Woodfill grabbed a pick that was in the pit and clubbed the two German soldiers to death. Exhausted and suffering from the effects of exposure to mustard gas – a chemical explosive shot by German artillery -Woodfill safely made it back to American lines. He was hospitalized at Bordeaux and saw no further action during the war.

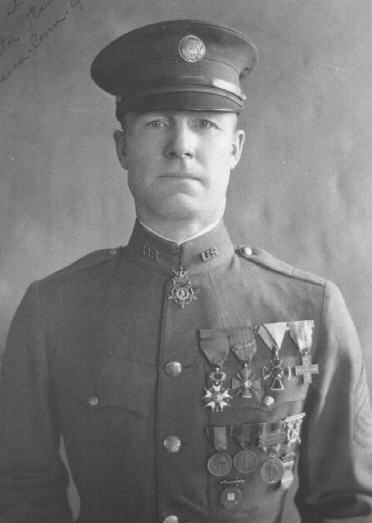

For his courage in that one morning of service, Woodfill received the Medal of Honor – American’s greatest military honor – in ceremonies at Chaumont, France, on February 9, 1919. General Pershing presented the medal to Woodfill. The French government decorated him with the Croix de Guerre with palm and made him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. The Italian government presented Woodfill with its Meriot di Guerra, and the government of Montenegro honored Woodfill with its Cross of Prince Danilo, First Class. Woodfill also was promoted to the rank of Captain.

In an account published on April 11, 1919, Mrs. Woodfill told a Kentucky Post reporter her husband wrote her about his experiences, but he had neglected many of the details. It was not until she was invited to see a newsreel re-enactment of the incident that Mrs. Woodfill learned the danger in which her husband had been. She said her concern was not about his medals but about when he was coming home. The account said Woodfill had written in a letter that he would be home in about six months. Woodfill’s term in the military apparently ran out that year because a Kentucky Post account on December 16, 1919, said Woodfill had reenlisted. But he apparently lost his rank in the reenlistment. A later account said Woodfill retired in 1923 with the rank of Sergeant. There was a local movement, apparently unsuccessful, to get the Congress to pass a special act allowing Woodfill to retire as a Sergeant, but with a Captain’s pension.

In 1921 Woodfill was selected as one of three World War I veterans to represent the Army in ceremonies dedicating the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery.

Locally, Woodfill was honored in July 1922 when the cornerstone was laid for a new Fort Thomas school at Alexandria Pike and Fort Thomas Avenue, which was named in Woodfill’s honor.

Despite his honors, Woodfill – on a Sergeant’s salary – struggled to pay his bills and to pay off the mortgage on his Fort Thomas home. Woodfill took a job in 1922 as a $6-a-day carpenter working on the Ohio River dam project at Silver Grove. Ned Hastings, manager of the Keith Theater in Cincinnati, sent pictures of Woodfill working at the dam site to New York. There a theatrical group involved in charitable work raised money to pay off the mortgage on Woodfill’s Fort Thomas home and to pay up an insurance policy.

In 1924 an effort was made by some independent Democrats to Woodfill to run for Congress and challenge Democrat incumbent Arthur B. Rouse. A Kentucky Post account on April 16, 1924, said Woodfill had expressed an interest in Congress while attending a reception in Washington, DC, three years before during the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. When Woodfill was proposed as a candidate for Congress, he was out of town doing promotional work for American Legion posts in Massachusetts. Mrs. Woodfill, contacted at her home in Fort Thomas, downplayed the idea. She said when her husband was first contacted to participate in the dedication event, he had expressed reluctance, saying, “I’m tired of being a circus pony. Every time there is something doing they trot me out to perform.” Mrs. Woodfill said her husband disliked public events because he was basically a bashful person who did not enjoy the glare of public attention. She added, though, “My husband may not have the education of a lawyer, scholar or the like, but if reputation, honesty, service and truth were the only requisite, he is amply qualified to fill the high position to which his friends would elect him.” Upon his return to Northern Kentucky, Woodfill quickly put an end to candidate speculation, saying he wanted no part of elected office.

Locally, Woodfill remained a celebrity. In October 1924 a life-size painting of Woodfill was presented to Woodfill Elementary School by Mrs. Woodfill. The painting was to hang in the school along with copies of his citations and a brief history of his life. And in October 1928 Woodfill and his wife were the special guests of honor at the Greater Cincinnati Industrial Exposition. That account said Woodfill was living in retirement on a farm in Campbell County. A later account said Woodfill had purchased about 60 acres of farm land between Silver Grove and Flagg Springs in rural Campbell County in 1925 with the vision of planting apple and peach trees. A report on July 24, 1929, said many of the trees died, so Woodfill purchased more trees. The account said he worked hard trying to make the orchard into a paying business, but the orchard never became a success.

By 1929 Woodfill found himself with a $2,000 debt. To keep from losing the farm, the 46-year-old Woodfill took a job as a watchman at the Newport Rolling Mill on July 15, 1929 – working daily from 2 pm to 11 pm. Woodfill was still working as a guard at the Andrews Steel plant in Newport and living at his home in Fort Thomas when the US entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

In May 1942, Woodfill and Alvin C. York – himself a highly decorated World War I veteran from Tennessee – were commissioned Army majors. Woodfill told a Kentucky Times-Star reporter at the time he was not aware the Army was going to give him the commission, which he termed a pleasant surprise. Woodfill was 59 and the Army commissions were part of a national campaign to boost national spirit and enlistments. Woodfill was later featured in an Army publicity picture, which showed him firing a rifle at Fort Benning, Georgia. Woodfill apparently spent most of the war as an Army teacher and instructor in Birmingham, Alabama.

His wife, Lorena, died March 26, 1942, at Christ Hospital in Cincinnati. An account said she was buried in Falmouth. In 1944 Woodfill again resigned from the Army, and he retired to a farm near Vevay in Jefferson County, Indiana. Because his wife had died, Woodfill decided not to return to Fort Thomas.

In a 1978 Kentucky Post story, Agatha Sackstedder, who grew up in a house across the street from the Woodfills, described Mrs. Woodfill as tall and elegant. She added that cookies and a big bowl of fresh fruit were always on the family table. She said the Woodfills had no children and Mrs. Woodfill seemed to enjoy having a young girl visit her. Mrs. Sackstedder described Woodfill as a strong looking, very tall man with a ruddy, happy looking face.

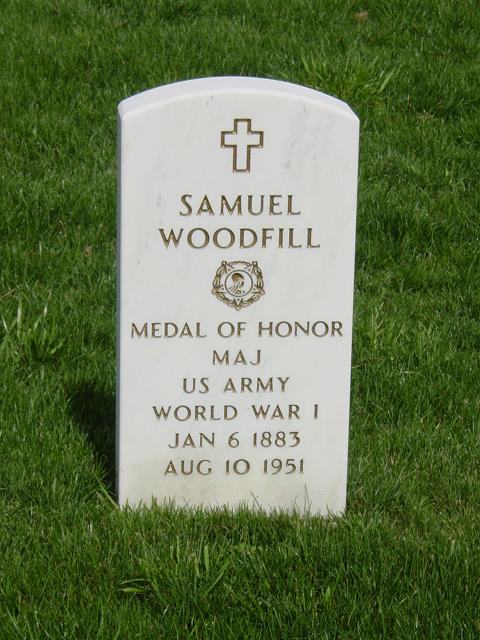

Woodfill was found dead at the Indiana farm on August 13, 1951, at the age of 68. He apparently had died of natural causes several days before he was found. Neighbors said they had not missed him because he had talked of going to Cincinnati to buy plumbing supplies. Despite his Indiana roots, a Kentucky Post editorial on August 15, 1951, called Woodfill “one of the greatest soldiers produced by the Bluegrass state.” Woodfill was buried in the Jefferson County Cemetery near Madison, Indiana. But through the efforts of Indiana Congressman Earl Wilson, Woodfill’s body was removed and buried at Arlington National Cemetery in August 1955.

WOODFILL, SAMUEL

- MAJ U S A 60 INF 5 DIV

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF BIRTH: 01/06/1883

- DATE OF DEATH: 08/10/1951

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 10/17/1955

- BURIED AT: SECTION 34 SITE 642-A

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

WOODFILL, SAMUEL

Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, U.S. Army, 60th Infantry, 5th Division. Place and date: At Cunel, France, 12 October 1918. Entered service at: Bryantsburg, Indiana. Birth: Jefferson County, Indiana. G.O. No.: 16, W.D., 1919.

Citation

While he was leading his company against the enemy, his line came under heavy machinegun fire, which threatened to hold up the advance. Followed by 2 soldiers at 25 yards, this officer went out ahead of his first line toward a machinegun nest and worked his way around its flank, leaving the 2 soldiers in front. When he got within 10 yards of the gun it ceased firing, and 4 of the enemy appeared, 3 of whom were shot by 1st Lt. Woodfill. The fourth, an officer, rushed at 1st Lt. Woodfill, who attempted to club the officer with his rifle. After a hand-to-hand struggle, 1st Lt. Woodfill killed the officer with his pistol. His company thereupon continued to advance, until shortly afterwards another machinegun nest was encountered. Calling on his men to follow, 1st Lt. Woodfill rushed ahead of his line in the face of heavy fire from the nest, and when several of the enemy appeared above the nest he shot them, capturing 3 other members of the crew and silencing the gun. A few minutes later this officer for the third time demonstrated conspicuous daring by charging another machinegun position, killing 5 men in one machinegun pit with his rifle. He then drew his revolver and started to jump into the pit, when 2 other gunners only a few yards away turned their gun on him. Failing to kill them with his revolver, he grabbed a pick lying nearby and killed both of them. Inspired by the exceptional courage displayed by this officer, his men pressed on to their objective under severe shell and machinegun fire.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard