Born on October 16, 1898, he served in World War I and subsequently began a legal career.

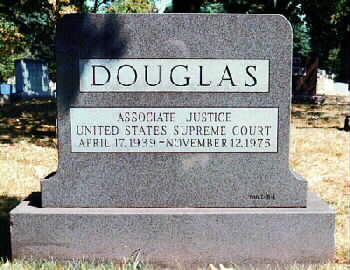

After being appointed to the United States Supreme Court, he served longer than anyone else in history (April 17, 1939-November 12, 1975).

He suffered a stroke and retired from the court, being replaced there by John Paul Stevens, who was nominted by President Gerald R. Ford.

He died on January 19, 1980 and was buried in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery, near the graves of Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and Potter Stewart, William J. Brennan and Thurgood Marshall.

Courtesy of The Washington Post:

Courting Trouble

‘Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas’ by Bruce Allen Murphy

Reviewed by Jeffrey Rosen

Sunday, March 9, 2003

WILD BILL

The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas

By Bruce Allen Murphy

Random House. 716 pp. $35

Reading the Supreme Court opinions of Justice William O. Douglas, it’s often hard to avoid the suspicion that they were scribbled on the back of a cocktail napkin. Breezy, polemical and unconcerned with the fine points of legal doctrines, they read more like stump speeches than carefully reasoned constitutional arguments. And now comes Wild Bill to confirm our darkest fears. According to Bruce Allen Murphy’s exuberant debunking of the longest-serving justice in American history, Douglas actually did scribble his opinions on scraps of paper (his staff called them his “plane trip specials”) on his way to weekends devoted to running for president or compulsive bouts of drinking and adultery with college students, flight attendants or any other women who crossed his path. Although Murphy says that Douglas “proved to be the one person who could and did make a real difference in the American judicial system,” the overwhelming impression left by his comprehensive biography is that Douglas hurt the cause of liberalism more than he helped it.

According to Murphy, the touchstone of Douglas’s character was a willingness to do anything to forward his own career — including lie about his past, break his promises and ruthlessly discard wives, children, friends and clerks as soon as they stopped being useful to him. He became the most sought-after law professor in the country by choosing his topics for their publicity value and hiring armies of law students to write his articles, which he would top off with “the Douglas flair.” Appointed to the Securities and Exchange Commission by President Franklin Roosevelt, he continued his relentless pursuit of publicity by going after high-profile symbols of corporate excess. (“Piss on ’em,” was his mantra to his staff.) And when Justice Louis Brandeis retired in 1939, FDR, who needed a Westerner and thought Douglas played an interesting game of poker, appointed him to the Supreme Court at the age of 40.

From the beginning, Douglas confessed that he “found the Court . . . a very unhappy existence” because, as his friend Tommy Corcoran put it, he “wanted the Presidency worse than Don Quixote wanted Dulcinea.” Roosevelt thought that Douglas would be the strongest running mate in 1944, but Democratic bosses persuaded him to pick Harry Truman instead. Truman actually asked Douglas to be his running mate in 1948, but Douglas refused on the grounds that he didn’t want to be “second fiddle to a second fiddle.” But he never abandoned his goal of becoming president, and when Kennedy won the Democratic nomination over Lyndon Johnson, who Douglas believed would have chosen him as a running mate in 1960, Douglas drank himself into a stupor, raving that “this always happens to me.”

Murphy suggests that Douglas’s political ambitions caused him repeatedly to lie about his past in a series of self-promoting autobiographies that were closer to fiction than fact. He turned a rambling manuscript about hiking into a national bestseller by inventing the claim that “it was . . . infantile paralysis that drove me to the outdoors.” In fact, his childhood illness was a recurring, psychosomatic intestinal colic. His law school classmates called him “the Approximate Mr. Justice Douglas” because he claimed to have graduated second in his class (at best he was fifth) and because he misstated the date of his first marriage to conceal that his first wife had put him through law school. And in a final act of self-invention, he arranged to be buried in Arlington Cemetery by claiming to have been a private in World War I. In fact, Murphy charges, Douglas never joined the Army and served only two months in the Student Officers Training Corps to avoid the draft. But a recent report in The Washington Post suggests that Murphy has inaccurately described the eligibility rules for burial in Arlington: As an associate justice who was honorably discharged from active duty, however brief, Douglas appears to have been technically eligible after all, according to a federal law in force when he died.

Douglas’s political ambitions influenced his positions on the Supreme Court as well, according to Murphy. He was a law-and-order conservative in the 1940s, when he still hoped to become president, but he became more sensitive to the rights of religious minorities in an effort to court the Catholic vote. By the 1950s, he had turned himself into a reliable civil libertarian, but his opinions became increasingly self-indulgent. “I’m ready to bend the law in favor of the environment and against the corporations,” he boasted. His most famous opinion, locating a right to privacy in “penumbras, formed by emanations” from the Bill of Rights, was justly attacked for its free-wheeling quality; a more legally rigorous derivation for privacy rights would have better served his cause. By the end of the 1960s, Douglas had become a judicial lounge act, ignored by his colleagues, who unanimously reversed his attempt to enjoin the bombing in Cambodia, and reduced to writing articles for Playboy and autobiographical plays about his political nemesis, Richard Nixon.

Murphy omits no details of Douglas’s private life, where he appears to have been something of a monster. His neglected children found him “scary” and noted that he spoke to them only when “press photographers wanted a picture.” They also resented his treatment of their mother, his first wife, whom he threw over after 28 years of marriage for a series of younger women. He left his third wife for a high school student who had asked him to sponsor her senior thesis, and then divorced her after 24 months for a college student whom he had met while she was a waitress in a cocktail lounge. He kept a room at the University Club, to which his messenger would drive Supreme Court secretaries who caught his fancy. In his sixties, he routinely invited flight attendants to visit him at the Court, where he would lunge at them in his chambers. He would not have survived the era of Anita Hill.

Murphy, the author of two other lively and respected works of Supreme Court muckraking, appears to take no special pleasure in unmasking his subject. But the only sympathetic moment in this relentlessly negative portrait occurs when Douglas, in an effort to prevent the construction of a parkway beside the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, challenges the editors of The Washington Post, who had supported the project, to a 185-mile hike. For eight days, the 55-year-old Douglas leads a diminishing pack down the tow path, undeterred by a freak snowstorm, poison ivy or the return of his old intestinal problems. Hiking along in the nature he loved, singing drinking songs, he seems almost human. But at the end, when he is standing in a boat and waving his Western hat in response to a “roaring welcome” from 50,000 people in Georgetown, one realizes the true point of the trip. For the first and only time in his life, Douglas was basking in the cheers of a crowd. •

Jeffrey Rosen teaches law at George Washington University and is the legal affairs editor of the New Republic.

In Further Review, It’s Hard to Bury Douglas’s Arlington Claim

By Charles Lane

Friday, February 14, 2003

In the matter of Justice William O. Douglas’s claim to a soldier’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery, the plot thickens.

Last week, this column reported on a forthcoming biography of the late Supreme Court stalwart that charges Douglas falsely claimed to be a World War I Army private — and raises questions about his burial in the nation’s most hallowed ground. Author Bruce Allen Murphy, a professor at Lafayette College, writes that Douglas’s stateside “[s]ervice as a private in the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) for [10] weeks at the end of World War I did not qualify one for burial in Arlington as a military figure.” Douglas was not formally inducted into the Army, and he had no honorable discharge, Murphy writes. The book implies that Douglas joined the SATC to stay out of the draft.

In response to additional questions from The Post, Murphy faxed a statement that said his conclusions were based on “dozens of documents, reports and interviews with highly-reliable authorities.” He said that “the status of SATC members was vastly different from that of soldiers on regular active duty” who were “subject to being posted to the front lines in Europe.”

There is “no question,” Murphy added, that Douglas’s “military service alone” was not enough to make him eligible for burial in Arlington — though his career on the court makes it “appropriate.” But the story is made more complicated — and apparently far less damning of Douglas — by documentary evidence not cited in Murphy’s book, “Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas,” to be published by Random House.

Under Section 553.15 of Title 32 of the United States Code, which was in force when Douglas died in 1980, burial at Arlington is automatically permitted to any former associate justice whose “last period of active duty (other than for training) as a member of the Armed Forces terminated honorably.”

Thus, all Douglas’s family had to show was that he once served on active duty for as little as a day, and had an honorable discharge, according to Tom Sherlock, Arlington’s official historian.

Records in the William O. Douglas Papers at the Library of Congress show that Douglas, then a student at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash., received instruction at a Reserve Officers Training Corps camp at the Presidio in San Francisco from June 3 to July 3, 1918, then served from Oct. 4 to Dec. 10, 1918, in the SATC on the Whitman campus.

During its brief existence, the SATC, devised by the War Department to develop officer material, enrolled more than 150,000 students at more than 500 campuses nationwide. It went out of business on Dec. 10, 1918, because of the armistice in Europe.

But Douglas’s papers do include a copy of a Dec. 10, 1918, “Honorable Discharge from The United States Army,” which identifies him as “William O. Douglas, Serial No. 5200182, Private S.A.T.C., Whitman College, U.S. Army.” The two-page document, signed by Capt. Chris Jensen, notes that Douglas was “inducted” on Oct. 4.

The Sept. 24, 1918, War Department regulations establishing the SATC, available from the U.S. Army Military History Institute at Carlisle, Pa., specify that “upon admission to the Students’ Army Training Corps a registrant becomes a soldier in the Army of the United States. As such, he is subject to military law and military discipline.” The regulations add: “Members of the Students’ Army Training Corps will be placed upon active-duty status immediately.”

The SATC, then, was clearly conceived of as a form of active-duty Army service. Indeed, the regulations call the SATC “a corps of the United States Army.” The SATC was not, as Murphy writes, “the World War I version of ROTC,” which was set up in 1916 as a separate entity.

Murphy is right that service in the SATC was hardly a combat tour. Many units around the country, including Douglas’s at Whitman College, lacked basic equipment, and the sometimes hapless participants were mocked by some as the “Saturday Afternoon Tea Club” or “Safe At The College.”

Douglas was taking a bit of license when he wrote, in a 1974 Supreme Court opinion, that “soldiers, lounging around, speak carefully of officers who are within earshot. But in World War I we were free to lambaste General ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, who was distant, remote and mythical. We also groused about the bankers’ war, the munitions makers’ war in which we had volunteered.”

There is also the issue — though Murphy does not raise it — that the SATC was, as its name suggests, a training outfit, and the Arlington eligibility rules say that active duty must be “other than for training.”

But Arlington historian Sherlock said this rule was “probably not” written with the obscure, long-defunct SATC in mind, and has been interpreted to refer to reservists whose only active service consisted of weekend or summer duty. An active-duty recruit whose service was limited to boot camp would qualify, Sherlock said.

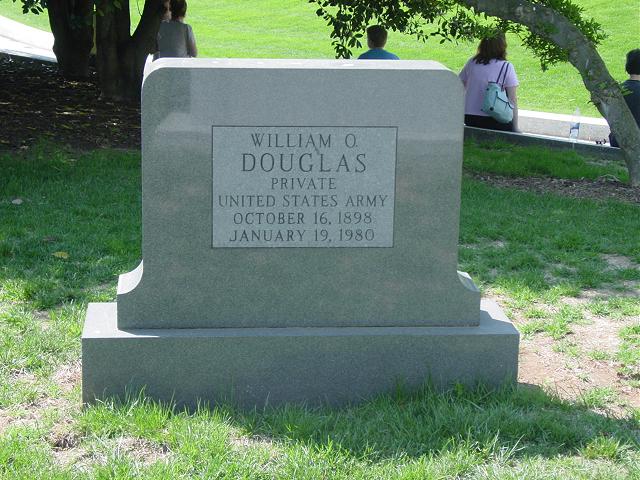

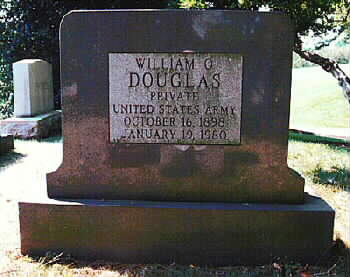

Legally, then, Douglas may have had a plausible claim to be a “Private, U.S. Army,” as his headstone at Arlington reads.

“Douglas had a federal service number, which is honorable federal military service, and that’s the only thing we’d look at,” Sherlock said. “The key is not what we’d consider active-duty service today, but that they considered it active duty then.”

Douglas’s Military Claim Questioned by Biographer

By Charles Lane

Monday, February 3, 2003

William O. Douglas, the liberal firebrand who served as a Supreme Court justice longer than anyone else in history, has lain since his death in 1980 at Arlington National Cemetery, under a headstone that reads, in part: “Private, United States Army.”

But now Douglas’s eternal rest is about to be disturbed by a charge from a scholar of court history who has concluded, based on extensive archival research and interviews with Douglas’s old acquaintances, that the justice’s claim to have served in the military during World War I is false.

If these assertions, which are made in a forthcoming biography of Douglas by Lafayette College professor Bruce Allen Murphy, are true, it would mean that Douglas obtained burial at Arlington even though he may not have been entitled to it. Though Murphy acknowledges that “after Douglas’ great service to the nation on the Supreme Court he deserved to be buried at Arlington,” that honor was reserved for honorably discharged veterans of the U.S. military. Others could gain admission only by special order of the president.

It is perhaps fitting that Douglas should be the focus of controversy in death, because few justices aroused more of it during their lifetimes.

Appointed to the bench by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939, Douglas scandalized Washington by divorcing and remarrying three times while on the court. His penchant for speaking out on foreign policy subjects and accepting payments from private foundations made him the focus of four unsuccessful impeachment efforts in Congress.

But Douglas also had a passionate following, based not only on his judicial philosophy, but also on his personal story, which, according to his memoirs, was that of a poor kid who emerged from Yakima, Wash., to conquer Wall Street, the Ivy League and Washington, D.C., through hard work and brains. Among the achievements he claimed — and that have heretofore been accepted by historians — were victory over polio in early childhood and a second-place rank in his class at Columbia Law School.

Yet in his book, advance galleys of which are being circulated by Random House, Murphy debunks those and other claims. For example, though Douglas wrote that he worked his way through Columbia, he actually depended on the income of his first wife, Mildred, a schoolteacher. Douglas got around this by reporting the date of their marriage as a year later than it actually was.

Murphy writes that Douglas’s military service consisted of a few months as a private in the now-defunct Student Army Training Corps (SATC) at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash.

The students who participated in this organization, Murphy says, marched around campus without guns, boots or uniforms, and Douglas was sidelined by influenza for much of the time. When uniforms finally arrived after the November 1918 armistice, Douglas suited up for a photo, but his military record, Murphy writes, shows that he was never actually inducted into the Army or honorably discharged, and never served in France, as many people apparently assumed.

Douglas did not enlist when the United States entered the war in 1917, Murphy argues, because at the time he was younger than 21 and would have needed parental permission, which his overprotective mother would have surely denied. After the draft age was lowered to 18 in August 1918, when Douglas was almost 20, he joined the SATC. He served for just over two months, from Oct. 1 to Dec. 10, when the unit was dissolved because the war was over.

Murphy quotes one of Douglas’s fellow SATC members as implying that they entered the outfit to avoid true military service. “We had to be there,” Hallam Mendenhall told Murphy. “If we hadn’t, we’d have been drafted.”

According to Murphy, Douglas was aided in this alleged résumé inflation by the fact that World War I-era military records were destroyed in a fire in 1973. Douglas asked his wife Cathy to have him buried at Arlington when the time came. Having no reason to doubt his story, she made the request, and officials went through the required background check.

Finding nothing in the records to dispute the claim, they accepted Douglas’s version, Murphy writes.

Cynthia Riddle, a spokeswoman for the Department of Veterans Affairs, which is responsible for confirming service records for those wishing to be buried at Arlington, said that Douglas’s records were indeed destroyed in the 1973 fire, but that a pay voucher survived showing that he drew a check from the Army for the period of his SATC participation. He even had a service number, 5200182, Riddle said.

A spokeswoman for Random House, Laura Moreland, said that Murphy is not giving any interviews until the book’s publication in early March. Douglas’s widow, Cathy Douglas Stone, was traveling and could not be reached for comment.

Why would such a brilliant and accomplished man embellish his already considerable achievements? In Murphy’s view, Douglas was a great disappointment — to himself. Having failed to attain his true ambition, the presidency, he felt the need to compensate in other ways. His 1950 memoir, “Of Men and Mountains,” which introduced the polio story, earned him public acclaim.

“Douglas now had what he always wanted,” Murphy writes. “He was finally number one in the public’s heart.”

Courtesy of The New York Times: 13 April 2003

Wild Bill’: Dirty Rotten Hero

By JAMES RYERSON

On his tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery, William O. Douglas is identified correctly as a former justice of the United States Supreme Court, and incorrectly as a former member of the United States armed forces. The error is significant, not only because Arlington National Cemetery reserves its plots for distinguished veterans but because Douglas himself was willfully responsible for the mistake. For 10 weeks at the end of World War I, the 20-year-old Douglas served in the Whitman College regiment of the Students’ Army Training Corps in Walla Walla, Wash., where he and his fellow trainees conducted unarmed predawn marches in their street clothes against imaginary enemies. He later described his wartime experience as a three-month stint in Europe as an Army Private, and recorded some of the putative details in an autobiography as well as a Supreme Court opinion.

How did a prominent public figure manage to lie about such a central fact of his biography? Probably the same way he lied about everything else: flagrantly, easily and in the service of his own rags-to-riches legend. In ”Of Men and Mountains,” a personalized travel guide to his native state of Washington, Douglas recalled his triumphant bout with polio at the age of 2, though in fact he had suffered from an intestinal colic. He frequently lied about his years as a student at Columbia Law School, falsely boasting, for example, that he had graduated second in his class. In his 1974 autobiography, ”Go East, Young Man,” he repeated many of these outright lies, introduced new ones and liberally embellished other key details of his life story. His widowed mother, for instance, was not destitute, but middle-class — though it’s true she was miserly and secretive about her money.

Douglas’s unabashed dishonesty is one of two revelations that give life to ”Wild Bill,” Bruce Allen Murphy’s tirelessly researched biography of the liberal judicial icon. The other surprise is what a rotten and unscrupulous person Douglas could be. A habitual womanizer, heavy drinker and uncaring parent, Douglas was married four times, cheating on each of his first three wives with her eventual successor. He so alienated his two children that they chose not to notify him when their mother, his first wife, died of cancer. When pressed for money, which was almost always, he was not above using insider information to make a quick buck in the stock market, or serving as the president of a foundation set up by a businessman with suspected ties to organized crime — an association for which Douglas narrowly avoided being impeached.

With these and other sordid discoveries, Murphy, the author of ”Fortas” and ”The Brandeis/Frankfurter Connection,” is well positioned to take Douglas to the mat, yet his portrait of the justice is ultimately a positive one. At one point, a former Supreme Court law clerk is quoted on the matter of Douglas’s personal failings: ”You just have to say to yourself, ‘You know, enough people are pains in the neck who don’t do anything worthwhile in their lives.’ ” This seems to be a fair statement of Murphy’s own attitude. In his 36 years on the court, Douglas was, in Murphy’s telling, a defender of the common good whose opinions on privacy, civil liberties and the environment made him ”the one person who could and did make a real difference in the American judicial system.” It’s refreshing to see a biographer who can keep separate his judgments about his subject’s personal and intellectual lives. In this case, however, it’s not clear that Murphy should have been so generous.

No sooner had President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Douglas to the Supreme Court in 1939 than he became bored with the job. He had previously served as the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, aggressively reforming Wall Street in the aftermath of the nation’s financial collapse. The staid court, by contrast, forced one ”to wait for the food to come washing up to your mouth with the high tide,” as he put it, borrowing an image from Oliver Wendell Holmes. Antsy, he spent a great deal of time angling to leave the court for a political position that would give him a shot at the presidency.

Douglas’s legal opinions during this period, though reliably liberal, were often highly deferential to the government. In the 1946 case Zap v. United States, he wrote for the court in ruling that federal contractors automatically waive their Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights when contracting with the government. He also sided with the majority in the notorious 1944 Korematsu opinion affirming the constitutionality of the wartime internment of Japanese-Americans. If a guiding jurisprudential philosophy underlay his views, it involved, as Murphy concedes, ”determining which issues were in his own best interests, battling with his enemies and taking positions with an eye to his political future.”

By the mid-1960’s, Douglas had resigned himself to the fact that he would never escape the court for the White House, and his judicial stance became increasingly standoffish. This was a strange reaction if Douglas was indeed ”the one person who could and did make a real difference in the American judicial system,” for the court had become solidly liberal, and Douglas could have assumed an influential leadership role. Instead, he distanced himself even from Hugo Black, his ally in dissent in the early 1950’s, when the court was predominantly conservative. By the end of his career, Douglas had dissented in almost 40 percent of the decisions he faced, and in more than half of those dissents he wrote only for himself. Because the content of these later dissents was increasingly that of a hard-line civil libertarian, Murphy appears to see in Douglas an ideological shift for the good.

But was this a principled transformation or just Douglas’s preening, grandstanding and iconoclasm as they manifested themselves in a liberal environment? Murphy never attempts to explain the change in Douglas’s judicial worldview, other than to suggest that his later opinions expressed the democratic spirit and the ”desire never to be chained in,” which were fostered by growing up in the frontier town of Yakima. This interpretation not only fails to account for Douglas’s earlier opinions, but it risks succumbing to the very pioneer myth that Murphy has otherwise worked so diligently to dismiss. Absent a compelling ideological explanation, it’s hard to avoid the impression that Douglas was, on the court as well as off, a showboat and a troublemaker, and — as his nickname suggests — too wild for his own good.

James Ryerson is an editor at The Times Magazine.

The Anti-Hero

by Richard A. Posner

24 February 2003

Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas

by Bruce Allen Murphy

(Random House, 688 pp., $35.00)

I met Justice William Douglas, the longest-serving member of the Supreme Court, when I was clerking for Justice William Brennan. Douglas struck me as cold and brusque but charismatic–the most charismatic judge (well, the only charismatic judge) on the Court. Little did I know that this elderly gentleman (he was sixty-four when I was a law clerk) was having sex with his soon-to-be third wife in his Supreme Court office, that he was being stalked by his justifiably suspicious soon-to-be ex-wife, and that on one occasion he had to hide the wife-to-be in his closet in order to prevent the current wife from discovering her.

This is just one of the gamy bits in Bruce Allen Murphy’s riveting biography of one of the most unwholesome figures in modern American political history, a field with many contenders. Murphy explains that he had expected the biography to take six years to complete but that it actually took almost fifteen. For Douglas turned out to be a liar to rival Baron Munchausen, and a great deal of patient digging was required to reconstruct his true life story. One of his typical lies, not only repeated in a judicial opinion but inscribed on his tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery, was that he had been a soldier in World War I. Douglas was never in the Armed Forces. The lie metastasized: a book about Arlington National Cemetery, published in 1986, reports: “Refusing to allow his polio to keep him from fighting for his nation during World War I, Douglas enlisted in the United States Army and fought in Europe.” He never had polio, either.

Apart from being a flagrant liar, Douglas was a compulsive womanizer, a heavy drinker, a terrible husband to each of his four wives, a terrible father to his two children, and a bored, distracted, uncollegial, irresponsible, and at times unethical Supreme Court justice who regularly left the Court for his summer vacation weeks before the term ended. Rude, ice-cold, hot-tempered, ungrateful, foul-mouthed, self-absorbed, and devoured by ambition, he was also financially reckless–at once a big spender, a tightwad, and a sponge–who, while he was serving as a justice, received a substantial salary from a foundation established and controlled by a shady Las Vegas businessman.

For at least a decade before he was felled in 1974 by the massive stroke that forced his retirement from the Court a year later, Douglas (perhaps as a consequence of his heavy drinking) had been deteriorating morally and psychologically from an already low level. The deterioration manifested itself in paranoid delusions, senile rages and sulks, sadistic treatment of his staff to the point where his law clerks–whom he described as “the lowest form of human life”–took to calling him “shithead” behind his back, and increasingly bizarre behavior toward women, which included an assault in his office on an airline stewardess who had unsuspectingly accepted an invitation from this kindly seeming old man to visit him there. His third marriage, to a woman in her early twenties (the woman in the closet), lasted only two years, and began to disintegrate within weeks of the wedding. After that divorce Douglas speedily took up with two more women in their twenties, marrying one on an impulse but later resuming romantic relations with the other. This fourth marriage might well have dissolved had his stroke held off. As Murphy puts it, Douglas had “buyer’s remorse” in the marriage market.

Does any of this matter? It would not–had not Douglas in his autobiographical writings and elsewhere presented his life to the public as exemplary of American individualism and achievement. I cannot begin to imagine his thinking in publishing lies that were readily refutable by documents certain one day to be discovered.

William Orville Douglas was born in 1898 in Yakima, Washington. In his autobiography he claimed that his grandfather Orville had fought in Grant’s army at Vicksburg, when in fact Orville had deserted from the Union Army twice without ever seeing combat. Douglas’s father, an eccentric itinerant preacher notably neglectful of his children (like father, like son), died when Douglas, the couple’s firstborn son, was a young child. Douglas himself almost died of an intestinal disease as an infant. His mother hailed his recovery as a miracle. He became her “treasure” and she declared that he would someday be President of the United States, thus planting in him the seed of a lifelong ambition. It was also in his autobiography that Douglas reported having cured himself of polio by sheer force of will. He wanted to link himself to Franklin Roosevelt, whom he had hoped to succeed as president–with the difference of having actually cured himself of the disease, a feat beyond FDR’s ability.

Douglas claimed to have grown up in abject poverty. This was another lie: his mother had been left surprisingly well provided for as a widow, and the family, though poor by modern standards (as most people were a century ago), was middle class. What is true is that Douglas’s mother was very tight with money (another parental trait the son inherited, though this one only fitfully); and as a result Douglas believed until he was an adult that the family had been poor. His discovery of the truth led to a lifelong resentment against his mother, who he thought should have paid for him to attend Washington State University, which he believed would have led to his obtaining a Rhodes Scholarship. On his deathbed Douglas told his wife: “I want you always to know that no one has ever been better to me since my mother.” Douglas’s daughter told Murphy that this was actually an insult, given Douglas’s hostility toward his mother.

After graduating from Whitman College in Washington (Douglas claimed that at Whitman he had lived in a tent, when in fact he had lived in a fraternity house, though in hot weather the frat boys sometimes slept outside), Douglas taught high school for two years and then enrolled in Columbia Law School. He claimed to have arrived in New York, having ridden the brake rods of a train or possibly in an open boxcar, with just six cents in his pocket — all lies. By this time he was married, and his wife, a schoolteacher, was his major support in law school. He concealed this in his autobiography, in part by postdating his marriage by a year, and claimed to have worked his way through law school. He also claimed to have heard Caruso sing at the Metropolitan Opera House, though the tenor died the year before Douglas arrived in New York.

Of greater consequence, Douglas claimed to have graduated second in his law school class, which was not true, although he was a good student, and made the law review, and was hired by the Cravath firm (despite looking, according to John J. McCloy, the associate who hired him, like “a singed cat”), then as now a leading Wall Street firm. He quit after four and a half months and fled back to Yakima, his hometown, hoping to practice law there but abandoning the idea after just four days. A spell of unemployment followed, during which he was supported by his wife. He returned to the Cravath firm for seven months and then went into teaching, first at Columbia and then at Yale, where he represented himself as having been a successful Wall Street lawyer. He also claimed to have practiced law in Yakima; he had not.

His academic career was short, lasting from 1927 to 1935, but it was spectacularly successful. Attracted as a student to legal realism, of which Columbia was the hotbed, as a professor he quickly became a prominent member of the movement. Yale soon hired him away from Columbia, with which he had become disaffected by the school’s failure to appoint a legal realist as dean. He had made a tremendous impression on Robert Maynard Hutchins, Yale’s young dean. When shortly afterward Hutchins became president of the University of Chicago, he offered Douglas an appointment and Douglas accepted, and he was listed for two years in the Chicago catalog as a member of the faculty visiting at Yale. But he never taught at Chicago, instead using his dual status to extract a Sterling professorship and high salary at Yale. He was a consummate careerist.

he legal realists recognized that law is not an autonomous body of thought. (The belief that it is autonomous, and that judges arrive at their decisions by a process of deductive logic or something akin to it, is known as legal formalism, and it retains to this day a strong hold on the legal imagination.) According to the realists, law is an instrument of social policy, and intelligent reform therefore requires an understanding of the consequences of law, an understanding that is itself dependent on social science and empirical inquiry. Douglas knew no social science, but he understood the value of grounding analysis of business law in empirical inquiry, and he organized and supervised a number of ambitious empirical projects. His articles and his casebooks quickly made him a coming figure in corporate and bankruptcy law.

Yet he had plenty of time for boozing, girls, and practical jokes. Once, when the dean of the law school was too drunk to find his way to the railroad station to catch a train to a city in which he was to give a speech, Douglas considerately drove him to the station–and put him on a train to a different city. Another time Douglas sent a note to one of his colleagues that he purported to be from an admirer named Yvonne, who gave her phone number and suggested that they meet for cocktails. When the colleague dialed the number, he discovered that he was calling the city morgue. Douglas’s sense of humor also expressed itself in his connoisseurship of popular-song titles, such as “Songs I Learned at My Mother’s Knee and Other Low Joints” and “My Wife Ran Off With My Best Friend, and I Sure Miss Him.”

Legal realism made a natural fit with the New Deal, and a number of faculty members and recent students at Yale went off to work for federal agencies. Douglas, quickly spotting securities law as an emerging field and becoming an expert in it, became a member of the Securities and Exchange Commission and before long its chairman. His two years as chairman brought notable successes in efforts to regulate the stock exchanges and made him a hero of the second New Deal. Murphy’s account of the Wall Street scandals of the period has a surprisingly contemporary ring.

Douglas, according to legal historian (and former Douglas law clerk) Dennis Hutchinson, “found it easy to elbow his way into the back rooms of power through a combination of a reputation for capability, cheek, skill at losing poker games, and drinking hard with the boys.” When Brandeis retired from the Supreme Court in 1939 and there was a clamor to appoint a Westerner to the Court, Roosevelt picked Douglas. He was forty. He was also Brandeis’s personal choice to succeed him.

t took Douglas only a few weeks to discover that being a judge was not to his taste. He missed the excitement of jousting with the Wall Streeters, and he viewed his new job primarily as a stepping stone to the presidency. He came close to being nominated for vice president on the Democratic ticket in 1944; had he been the nominee, he rather than Truman would have become president when Roosevelt died the following year. Bitterly disappointed, he continued to nurse presidential ambitions. He almost accepted the Democratic nomination for vice president in 1948–Truman was desperately eager to have him on the ticket–and probably would have done so had he thought Truman would lose the election, in which event he could expect to inherit Truman’s mantle as leader of the Democratic Party. But he shrewdly recognized that Dewey would lose.

As late as 1960, Douglas was still considering a political career. Lyndon Johnson, one of his pals (Douglas tended to clump together with other persons of unsavory personal character), promised Douglas that if he was nominated for president he would make Douglas the vice presidential nominee. Douglas was bitter at the Kennedys for ruining his chances by “buying” the 1960 nomination for JFK. His bitterness provoked a memorable alcoholic binge that Murphy vividly describes.

Douglas’s divorce from his first wife in 1954 had placed him in a financial bind from which he never entirely escaped. Her lawyer, egged on by Tommy Corcoran, another of Douglas’s unattractive friends from the New Deal days turned enemies, had ingeniously inserted in the divorce settlement an escalator clause whereby the more money Douglas made from his books and lectures, the more he had to give her in alimony–and she lived for a long time and did not remarry. He was now on a financial treadmill. Besides his income from the dubious Parvin Foundation, he lectured constantly and wrote book after book, mainly travel books; he was heavily dependent on publishers’ advances. He employed an editorial assistant who eventually became a ghost co-writer of his books.

In the 1940s, when Douglas had thought he had a shot at the presidency, he had been a liberal justice, but respectably so–to the right, for example, of Frank Murphy. In the 1950s, however, he and Hugo Black formed the extreme liberal wing of the Court, and he moved steadily leftward from there, to the point where even in the heyday of the Warren Court in the 1960s Douglas was to the left of any other justice. He became a bête noir of the right and survived three efforts to impeach him, the third a serious one that was blocked by Democratic control of the House of Representatives. The second impeachment effort was provoked by his sensible if premature suggestion–it was during the Korean War–that the United States should begin to cozy up to Communist China in order to divide it from the Soviet Union, a suggestion that later became the foundation of the hated Nixon’s foreign policy.

Douglas became a hero not only to radicals and civil libertarians but also to environmentalists. He may not have liked any human being, but he loved nature; and by his books and his personal example, including a well-publicized 185-mile hike along the Chesapeake & Ohio canal towpath in a successful protest against the building of a highway on it, Douglas helped give visibility to the nascent environmental movement. I had a scrape with Douglas’s environmentalism when I worked in the solicitor general’s office in the 1960s. We sided with the Bonneville Power Administration (part of the Department of the Interior) in a fight with the Federal Power Commission over whether Bonneville or a private power company would build a hydroelectric dam on the Snake River in Idaho. We won the case, which was gratifying, but we were astonished at Douglas’s opinion, which declared without basis in the record or the arguments of the parties that no one should build the dam, because it would harm the salmon, and anyway solar and nuclear power would soon supplant the need for further hydroelectric power.

From my account, Murphy’s book may seem a hatchet job, with its mountain of often prurient detail about Douglas’s personal life and character. Not so. Murphy displays no animus toward Douglas. He does not try to extenuate Douglas’s failings as a human being, or to excuse them, or even to explain them, but he greatly admires Douglas’s civil liberties decisions, and (without his actually saying so) this admiration leads him to forgive Douglas’s flaws of character. The only time his realism regarding Douglas’s character falters is when he is discussing Felix Frankfurter. His portrayal of Frankfurter is relentlessly and excessively critical; he sees Frankfurter exclusively through Douglas’s hostile eyes.

Murphy is right to separate the personal from the judicial. One can be a bad person and a good judge, just as one can be a good person and a bad judge. With biography and reportage becoming ever more candid and penetrating, we now know that a high percentage of successful and creative people are psychologically warped and morally challenged; and anyway, as Machiavelli recognized long ago, personal morality and political morality are not the same thing. Douglas was not a good judge (I will come back to this point), but this was not because he was a woman-chaser, a heavy drinker, a liar, and so on. It was because he did not like the job. In part he did not like it because he wanted another job badly, a job for which he was indeed better suited. Roosevelt may have made a mistake in preferring Truman as his running mate in 1944. Not a political mistake: Douglas had never run for elective office, and the Democratic Party bosses, whose enthusiastic support FDR thought essential to his re-election, were passionate for Truman. If passing over Douglas was an error (which we shall never know), it was an error of statesmanship. With his intelligence, his toughness, his ambition, his leadership skills, his wide acquaintanceship in official Washington, his combination of Western homespun (a favorite trick was lighting a cigarette by striking a match on the seat of his pants) and Eastern sophistication, and his charisma, Douglas might have been a fine Cold War president.

At least a Douglas administration would not have been afflicted by the cronyism that so undermined Truman’s presidency. Douglas had his own cronies, many with character flaws similar to his own, like Lyndon Johnson and Abe Fortas, but they were abler and less manifestly corrupt than Truman’s cronies. And unlike Henry Wallace, the vice president whom FDR providentially dropped at the end of his third term in favor of Truman, Douglas was not soft on communism. I do not think that he was ideological at all; he was merely ambitious. I doubt even that he was, despite his later judicial record, a genuine liberal. Douglas was just ornery and rebellious and publicity-seeking: “always fame was the spur,” as Ronald Dworkin, one of Douglas’s liberal critics, put it.

Thus Douglas’s hostility to Frankfurter seems to have been based on professional jealousy rather than on political or jurisprudential disagreement. Come the 1950s and the dimming of his presidential prospects, Douglas gave his rebellious instincts full rein and reveled in the role of the iconoclast, the outsider; he became the judicial Thoreau. Later, when he himself had become an icon of the left, he claimed that had he been president he would not have dropped the atomic bomb on Japan, and would have recognized Red China, and so forth; but these claims cannot be taken very seriously, especially given his complete lack of respect for truthfulness.

Where Murphy can be faulted, though I think not severely, is for his uncritical treatment of Douglas’s judicial performance. Other recent judicial biographies, such as the very distinguished biographies of Learned Hand by Gerald Gunther, of Benjamin Cardozo by Andrew Kaufman, and of Byron White by Dennis Hutchinson, have maintained a good balance between the judge’s life and his work. But those biographers were dealing with much less interesting personalities; and after fifteen years and seven hundred pages Murphy was entitled to call it a day. About all he does with Douglas’s judicial product is quote from a handful of his civil liberties opinions.

The quotations are effective in demonstrating that Douglas was an able judicial polemicist and had the good sense to write his own opinions rather than rely on law clerks, even if they are not really the lowest form of human life. Still, taken as a whole, Douglas’s judicial oeuvre is slipshod and slapdash. Here are typical criticisms, none of them by conservatives. “His opinions were not models; they appear to be hastily written; and they are easy to ignore” (Lucas Powe). Their carelessness is rooted in “indifference to the texture of legal analysis, which arises from an exclusively political conception of the judicial role” (Yosal Rogat). “Douglas was the foremost anti-judge of his time” (G. Edward White). A careful study of his tax opinions by Bernard Wolfman and others has documented Douglas’s unreasoning hostility to the Internal Revenue Service and accuses him of “refusing to judge in tax cases.”

he Supreme Court is a political court. The discretion that the justices exercise can fairly be described as legislative in character, but the conditions under which this “legislature” operates are different from those of Congress. Lacking electoral legitimacy, yet wielding Zeus’s thunderbolt in the form of the power to invalidate actions of the other branches of government as unconstitutional, the justices, to be effective, have to accept certain limitations on their legislative discretion. They are confined, in Holmes’s words, from molar to molecular motions. And even at the molecular level the justices have to be able to offer reasoned justifications for departing from their previous decisions, and to accord a decent respect to public opinion, and to allow room for social experimentation, and to formulate doctrines that will provide guidance to lower courts, and to comply with the expectations of the legal profession concerning the judicial craft. They have to be seen to be doing law rather than doing politics.

Douglas was largely oblivious to these rather modest requirements, with which he could easily have complied had he had just a little Sitzfleisch. He liked to say that “I don’t follow precedents, I make ’em.” Yes, that is what Supreme Court justices do much of the time; but they are supposed to explain why, and in precisely what sense and to what degree, they are departing from precedent. Douglas’s disdain for judicial norms is easily illustrated. On a number of occasions he issued stays–which were quickly and unanimously overturned by his colleagues–intended to halt American participation in the Vietnam War on the ground that Congress had not declared war. One can argue from the language of the Constitution that the United States cannot lawfully wage war without a congressional declaration, but the argument depends on a literal interpretation of the Constitution–an interpretation that would also forbid military aviation on the ground that the Constitution expressly authorizes the creation only of land and naval forces–which Douglas contemptuously rejected in every other area of constitutional law. It was Douglas, after all, who had the audacity to rule in Griswold v. Connecticut, the first case to establish a right of sexual autonomy and hence a precursor of Roe v. Wade, that the Court could fashion new constitutional rights based not on the text of the Constitution but on the values underlying it; and so the Third Amendment, which forbids the quartering of troops in private homes in peacetime, became a source of the constitutional right declared in Griswold of married couples to use contraceptives.

The most interesting question about Douglas’s judicial performance is whether its deficiencies can be blamed to any extent on legal realism, to which he had committed himself as an academic. Suppose that, upon being appointed to the Court, he had abandoned his political ambitions and set as his goal to become the greatest justice in history. The combination of his youth, his intelligence, his energy, his academic and government experience, his flair for writing, the leadership skills that he had displayed at the SEC, and his ability to charm when he bothered to try (rare as that was, except when he was courting) would have put him within reach of the goal. He was not a genius, as some of his ex-wives and judicial colleagues claimed. He was a very fast worker, which is not the same thing, especially when speed is the product of restlessness and impatience. (He wrote some of his opinions in twenty minutes.)

But law is not the calling of geniuses. There has never been a genius on the Supreme Court, unless it was Holmes. Douglas was certainly very able. Would a commitment to legal realism have stopped him well short of the goal by breeding a cynicism about law that would have prevented him from taking his job entirely seriously? I think that the opposite is more likely, and that the tragedy of Douglas was not that he was a warped human being, or that Roosevelt passed him over for the vice presidential nomination, but that for reasons of temperament–and because the great prize of the presidency seemed for a while within reach–he could not buckle down and commit himself wholeheartedly to the Court and become the greatest of the legal realists.

For it is not true that a judge cannot achieve greatness without embracing formalism. John Marshall, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Robert Jackson were realist judges. Many of the criticisms leveled against Douglas have been leveled against them (and other realists as well), but they have bounced off them because, unlike Douglas, they took the judicial process seriously–even Jackson, whose presidential longings were as intense as Douglas’s. For Douglas, law was merely politics. Had he brought to bear all his powers, which were considerable, and injected greater realism and empirical understanding into the work of the Supreme Court, he might have achieved greatness. He could still have summered in the Cascades and chased young women, though he would have been well advised not to marry them, and to go easy on the booze.

The information resource you have published on the Internet: William Orville Douglas https://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/wdouglas.htm has been cited in The Infography as one of the most excellent sources of information available for learning about “U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard