In Washington, D.C., on one snowy January night in 1871, Vinnie Ream became famous. On that night her white marble statue of President Abraham Lincoln was unveiled in the United States Capitol building. She was only 23 years old.

Lavinia Ellen Ream was born on September 25, 1847, in a simple log cabin in Madison, Wisconsin. She was the youngest daughter of Robert and Lavinia Ream. Robert Ream was a surveyor and a Wisconsin Territory official. The Reams also operated a stage coach stop, one of the first hotels in Madison, from their home. Guests slept on the floor.

Winnebago Indians in Wisconsin taught Vinnie Ream to paint and draw during her childhood. When she was seven years old, the Ream family moved to Washington, D.C. There Ream had her first chance to model with clay in the studio of sculptor Benjamin Paul Akers, who said she showed talent. After a few years in Washington, the Ream family moved to Kansas so that Robert Ream could take a surveying job. During this time, Ream attended Christian College, a school for young women in Columbia, Missouri. She studied art, literature, and music.

In 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War, the Ream family packed up again and moved back to Washington, D.C. Only a teenager, Ream became one of the first women to work for the United States Postal Service, where she worked as a clerk from 1862 to 1866. To help with the war effort, Ream volunteered to write letters for wounded soldiers in the hospitals. She also sang in hospital concerts and for local churches. She had boundless energy. At one time she told her mother, “I feel that I am to have some special work in the world. I don’t know what it is, but I must be ready for it when it comes.”

Ream soon found out. In 1863 she visited the sculptor Clark Mills with Missouri Congressman James Rollins to ask for a sculpture for Ream’s old school in Columbia, Missouri. While watching the artist at work, Ream suddenly said, “I can do that.” Mills gave her some clay, which she molded into a medallion of an Indian chief’s head. Impressed with her skill, Mills asked her to be his apprentice. Ream continued with her postal clerk job and worked in Mills’ studio part-time. She started making relief medallions and portrait busts of congressmen and other public figures. These important men wanted to support the young sculptor, and in late 1864 several of them asked President Lincoln to let her model him for a bust. Unwilling at first, the President changed his mind when he learned that Ream shared his humble background. The experience of being with the President for half an hour a day for five months would change Ream’s life. After Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, Congress voted to commission eighteen-year-old Vinnie Ream to sculpt his full-size statue.

Vinnie Ream said that she felt Lincoln’s personality deep within her after modeling the great man’s portrait bust. Her work was so lifelike that she won the commission for the full-size figure over artists who were much better known. To get the measurements for the statue, she was given the clothing Lincoln had been wearing the night he was shot. She used Cararra marble, a special white marble from Italy that was a favorite of Michelangelo. Ream and her parents traveled to Italy to choose the purest stone. They lived in Rome for two years while Ream turned her plaster model into the finished marble figure.

Ream was the first woman and the youngest sculptor to win a commission from the government for a statue. She later built for Admiral David Farragut the first U.S. Naval Officer monument, which is in Farragut Square, Washington, D.C. She used bronze from the propeller of Farragut’s ship for his statue. In 1878 Vinnie Ream married Richard L. Hoxie, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. They lived in Washington, D.C., and had a summer home in Iowa City, Iowa. They had one son, Richard.

Ream gave up her sculpting career, but in the early 1900s she accepted two final commissions. Her last work was designing a full-size statue of Sequoyah, the first statue of a Native American to be placed in the Statuary Hall at the Capitol Building. Ream died in 1914 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Submitted By An Anonymous Source: January 2003

Vinnie Ream Hoxie

9-25-1847 to 11-20-1914

Hoxie, Vinnie Ream (September 25, 1847 – November 20, 1914), sculptor, daughter of Robert Lee and Lavinia (McDonald) Ream, was born in Madison, Wisconsin, then a frontier town. Part of her childhood was spent in Washington, D. C., where her father had found employment, but the family later returned to the West, and she attended Christian College, Columbia, Missouri. Here she wrote songs which were set to music and published. Moving again to Washington with her parents during the Civil War, she obtained a minor clerkship in the Post Office department at the age of fifteen. A friend having taken her to the studio of Clark Mills, she laughingly attempted to model a likeness of Mills; the result delighted her and others. Keeping her government position, she thenceforth gave all her free time to the study of sculpture, chiefly under Mills. She was small, slender, bright-eyed, with a wealth of long curls. Her personality was so winning, and the art of sculpture was at that time so little understood in the United States, that within a year, at senatorial solicitation, President Lincoln allowed her to come to the White House, giving her daily half-hour sittings, during five months. She was reverent, impressionable, industrious, gifted, but of course without sufficient training for the commission which, nevertheless, was awarded to her by Congress after a competition, to make a full-length marble statue of Lincoln for the Rotunda of the Capitol. A contract was signed August 30, 1866: $5,000 to be paid on acceptance of the full-size plaster model, and $5,000 on completion of the marble. Vinnie Ream was the first of her sex to execute sculpture for the United States government; she had impressive indorsement, both political and military. Armed with Secretary Seward’s letter of recommendation to the American diplomatic and consular representatives in Europe, the young sculptor, accompanied by her parents, went to Rome to put the statue into marble.

In her own country, she had already made from life portrait-busts of Thaddeus Stevens and others. Abroad, in more sophisticated circles, her frontier spirit of independence, coupled with her artlessly ingratiating demeanor, proved attractive. In Paris, she made portraits of Gustave Doré and Père Hyacinthe. According to the Reminiscences of Georg Brandes, the Danish critic (who pays tribute to her forceful, upright character, even while he smiles at her girlish vanity), she told him that in order to obtain a much-desired commission for a bust of the formidable Cardinal Antonelli, she had merely put on her most beautiful white gown, and obtaining an audience, had proffered her request, which was at once granted (1870). The cardinal gave her a medallion of Christ, inscribing it to his “little friend, Miss Vinnie Ream.” Other incidents attest her popularity. Her marble “Lincoln,” duly admired abroad, was unveiled with imposing ceremonies in the Rotunda in 1871. Although neither vigorous nor inspiring, the statue is imbued with sincere feeling and holds its own among its Capitoline companions as a remarkable production from a hand so inexperienced. Later she was awarded another government commission after competition: on January 28, 1875, she signed a twenty-thousand-dollar contract for the heroic bronze statue of Admiral Farragut now standing in Farragut Square, Washington, D. C., a work fairly representative of the average of its day.

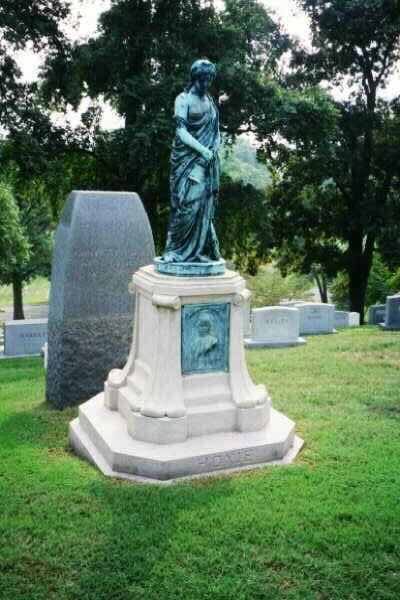

In 1878, before the completion of the “Farragut,” Vinnie Ream was married to Lieutenant Richard Leveridge Hoxie, United States army. The occasion was brilliant, even for Washington. Mrs. Hoxie became one of the popular hostesses of the city; for many years she gave up her art, only to return to it in later life. To her final period belong two works in Statuary Hall: the “Governor Samuel Kirkwood,” presented by the State of Iowa, and the “Sequoyah” (a statue of the Cherokee halfbreed who invented the Cherokee alphabet), the gift of Oklahoma. The model of the “Sequoyah,” finished shortly before Mrs. Hoxie’s death in Washington, was put into the hands of the sculptor George Zolnay. The completed bronze, placed in 1917, shows a technique somewhat more able than that seen in her earlier works. In addition to those already mentioned, the list of her sitters for portrait-busts or medallions include famous names: General Grant, General McClellan, General Frémont; Senator Sherman, Peter Cooper, Ezra Cornell, Horace Greeley, Liszt, Kaulbach, Spurgeon. Among her ideal figures are “The West,” “The Indian Girl,” “The Spirit of the Carnival,” “Miriam,” “Sappho.” A bronze copy of the “Sappho” was placed over her grave in the National Cemetery at Arlington, Virginia.

“She had a mind of many colors, and there was the very devil of a rush and Forward! March! about her, always in a hurry.” –Danish critic Georg Brandes.One of three children, two girls and a boy, Vinnie Ream was born in Madison, Wisconsin to Robert Lee Ream and Lavinia (McDonald) Ream. When she was ten her family moved to western Missouri where, for a short

time, she attended the academy section of Christian College in Columbia, Missouri and showed talent in music and art. With the onset of the Civil War the family was in Fort Smith, Arkansas and her father took up trade in the Real Estate business. they managed to work their way through Confederate lines and go to Washington, D.C., where her father, stricken with rheumatism, acquired a government job, and Vinnie became a clerk in the Post Office Department.

In 1863she went to the studio of sculptor Clark Mills in one of the wings of the Capitol building and wrote at a later date “I felt at once that I, too, could model and, taking the clay, in a few hours I produced a medallion of

an Indian chief’s head….” Mills was so awed by her, that he immediately took her on as a pupil. Before long she was sculpting busts of Congressman and other V.I.P.’s that came to the Washington area, including Senator John Sherman, General Custer, Francis Preston Blair, Thaddeus Stevens, and Horace Greeley. In the latter part of 1864 some friends arranged with President Lincoln for her to model a bust of him. The President refused at first. Upon hearing that she was a poor girl struggling on her own, he relented and gave her half-hour daily sittings for a period of five months. /She recalled later that she was “still under the spell of his kind eyes and genial presence” at the time that he was assassinated.

The bust she created won approval of her admirers. In the summer months of 1866 Congress awarded her a $10,000 contract to do a full-size marble statue of Lincoln which was to stand in the Capitol rotunda. She was the first woman to ever win such a federal commission. Criticism also came at the “incredulity” of an eighteen year old being awarded such. Mary Todd Lincoln expressed her disapproval, and Jane Swisshelm, a journalist, wrote that Vinnie’s success was based solely on her “feminine wiles.”

Once her plaster model was done in a studio in the Capitol, Vinnie went to Rome with her parents to turn it into marble. Secretary of State William

Seward gave her a letter of introduction to take along, and in 1869 she sailed for a two year residence in Rome. While there, Vinnie was painted by George P.A. Healy and Caleb Bingham. She did busts of Giacomo Cardinal Antonelli and Franz Liszt. Although Georg Brandes was critical of her vanity and her way of being “ingratiatingly coquettish towards anyone whose affection she wished to win,” he was still quite taken by her generosity and dedication to her work. He could only marvel at “her ingenuousness, her ignorance, her thorough goodness, in short, all her simple healthiness of soul.”

From the quarries of Carrara, she chose the purest white marble and under the tutelage of her teacher, Luigi Majoli, she used the model to create Abraham Lincoln in stone. In 1871 the finished staue was unveiled in the Capitol. The President’s head was bent slightly forward and his eyes fixed on someone as he extended to them the Proclamation with his right hand. It was an awesome production completed by an artist with no formal training, and Matthew Carpenter, a Senator from Wisconsin desrcibed the reaction: “Of this statue, as a mere work of art, I am no judge. What Praxiteles might have thought of such a work, I neither know nor care; but I am able to say, in the presence of this vast and brilliant assembly, that it is Abraham Lincoln all over.”

In 1875 Vinnie won a $20,000 federal commission to sculpt a bronze of Admiral David G. Farragut. She cast it from the propeller of Farragut’s ship the Hartford, he with telescope in hand, right foot resting on a tackle box and it was unveiled in Washington’s Farragut Square on May 28, 1878.

At the age of thirty, Vinnie married Lieutenant Richard Leveridge Hoxie. One son Richard Ream Hoxie was born in 1883. The family lived on Farragut Square, and Vinnie often played the harp for small gatherings of friends. She had given up her artistry at her husband’s wishes. In 1906 she returned for a short time to sculpture when the State of Iowa commissioned her to make a statue of Samuel Kirkwood, their Civil War Governor, for Statuary Hall in the Capitol building in Washington. Quite frail at the time because of a chronic kidney problem, her husband rigged a rope hoist and boatswain’s chair for her to be able to complete the statue.

Her last work was commissioned by the State of Oklahoma for a statue of Cherokee Chief Sequoyah. She was able to complete the model shortly before she died, and it was cast in bronze by George Zolnay. In the latter part of the summer of 1914, Vinnie had an acute attack of uremic poisoning. She was taken to Washington for treatment, and died there on November 20 of 1914. Episcopal services were held at St. John’s Church on Lafayette Square and she was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. How fitting that her grave should be marked by a replica of her ideal, a bronze statue of “Sappho.”

From a contemporary news report:

“Vinnie Ream Hoxie, who enjoyed the distinction of being the first woman of her profession to receive a commission from the Government, died today (November 20, 1914) after a long illness. She did Lincoln’s statue in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol and the figure of Admiral Farragut which stands in the square bearing his name in Washington, D.C. Born at Madison, Wisconsin and was in her 85th year. Among her best-known statues are those of Theaddeus Stevens, Governor Kirkwood and Albert Pike, the explorer.”

She was born on September 24, 1847 and lived in Washington on Farragut Square. She died on November 20, 1914 and is buried with her husband, Brigadier General Richard Leverdige Hoxie, in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.

In 1878 Ream married Lieutenant Richard Hoxie, then Chief Engineer Officer for the District of Columbia, whom she met while casting the Farragut statue at the Navy Yard.

President Ulysses S. Grant, General William T. Sherman, and most of the Senate attended their wedding. Ream’s marriage did not end her career but did slow it down as she began leading a somewhat conventional Washington social life in their house at 1632 K Street, N.W. She also left Washington a number of times to accompany her husband to other postings until his retirement from the Army in 1908 as a brigadier general. When Ream died in 1914 her husband placed a replica of her marble figure of the Greek poet Sappho on her tomb in Arlington National Cemetery.

HOXIE, VINNIE REAM W/O R L

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/12/1914

- BURIED AT: SECTION SOUTH SITE LOT 1876

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

- UNKNOWN RELATIONSHIP TO VETERAN

BRIG GEN

Impeachment furor of last century also

featured a charming young woman

October 18, 1998

More than a century before Monica Lewinsky became the woman some feared might finish a president, an attractive young sculptor named Vinnie Ream was blamed for saving one.

Ream was 20 years old in 1868 when she became the focus of a smear campaign by a Republican faction claiming she’d persuaded Sen. Edmund Ross, R-Kansas., to cast the deciding vote against the ouster of impeached President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat.

“They blamed her because they said she had used her wiles as a woman to influence Ross,” says Missouri state archivist Kenneth Winn, who is writing a book about Ream. “It’s somewhat murky as to what she actually did, but Republicans certainly felt she had influence.”

Ross was a boarder in the Ream family home. The families had known each other in Kansas, where Vinnie’s father was a surveyor before taking a government job in Washington.

Rumors had been following his daughter since at least 1866, when she became the first woman and, at 18, the youngest person ever awarded a federal commission. She was paid $10,000 to sculpt a marble statue of the slain Abraham Lincoln — an honor critics asserted had more to do with charm and political connections than artistic ability.

That same year, Ross arrived in Washington and moved in with the Reams, just as a faction of the GOP known as the Radical Republicans was taking off after Johnson. They felt the new president, a Tennessean, was being too soft on the defeated Confederacy.

To pressure the president, Congress passed a law requiring him to get Senate consent to dismiss appointed officials. When a defiant Johnson removed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the House impeached him for “impeding the will of Congress.”

The president went on trial in the Senate, where Radical Republicans assumed that Ross would side against Johnson.

But Ross refused to disclose his position, and rumors arose that Ream, believed sympathetic to Lincoln’s successor, was trying to sway the 40-year-old senator’s vote.

Winn cites contemporaneous accounts that described Ream as a charmer with a gleaming smile. She stood just 5 feet tall and weighed little more than 90 pounds. Photographs show dark flowing hair and dark eyes.

On the evening before the vote, Republicans sent an emissary to the Ream home to determine where Ross stood. Daniel Sickles, a Johnson foe since the president removed him from a military posting in the Carolinas, was also regarded as a ladies man who might charm the protective Ream into letting him see Ross.

Ream managed to put Sickles off for hours, serving tea and even singing for the one-legged Civil War veteran, Winn says. At various times, she whispered with someone behind a door, believed to be the reluctant Ross.

Finally, the frustrated Sickles asked Ream if she knew Ross’ intentions. She reportedly told him the senator would vote for acquittal.

As Sickles left the house at 4 a.m., he told Ream, “He is in your power and you chose to destroy him.”

Ross cast his “not guilty” vote later that day and a week later wrote to his wife: “Millions of men are cursing me today, but they will bless me tomorrow. But few knew of the precipice upon which we all stood.”

Ream and Ross steadfastly denied any impropriety, but Ross’ national career was doomed. Kansans voted him out. Years later, he became territorial governor in what is now New Mexico.

The young sculptor was stunned by the political furor swirling around her, says Glenn V. Sherwood of Longmont, Colo., a Ream descendant who spent a decade going through documents, including letters Ream wrote and congressional records, to write “Labor of Love, The Life and Art of Vinnie Ream.”

Republicans branded her a “female lobbyist,” then a sly bit of innuendo directed at women whose favors politicians sometimes traded among themselves. The House voted to evict her from her Capitol studio where she had worked two years on the Lincoln statue.

Ream fought back, and some sympathetic reporters took up her cause. The New York World wrote about the eviction campaign under the headline “How Beaten Impeachers Make War On Women.”

“This was a 20-year-old woman who knew how to manipulate men with lots of power,” Winn says. “Vinnie had a clear idea what she wanted to be and what she wanted to do.”

Her unlikely savior was Republican Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, who had led the fight to impeach Johnson. He convinced lawmakers just before his death that Ream should be able to keep

working in her studio.

The statue was unveiled in 1871 in the Capitol Rotunda, where it stands today.

Ream died in 1914 at age 67 and is buried along with her husband, Richard Leveridge Hoxie, a longtime Chief of Army Engineers, in Arlington National Cemetery.

Winn draws some parallels between Ream’s ordeal and what Ms. Lewinsky is going through.

“They were both about the same age and were hanging out with men that were more than twice their ages,” Winn says. “You might say that young women have had an effect on older men for a long time and can make them do very foolish things.”

New York Times Report On The Unveiling

Of Vinnie Ream’s Statue Of Lincoln

January 7, 1871

January 7, 1871

MISS REAM’S LINCOLN

Exhibition to the Secretary of the Interior — Description of the Statue– Merits as a Work of Art — Miss Reams at Rome.

From Our Own Correspondent.

Washington, Saturday, Jan.7, 1871.

The Secretary of the Interior, on the invitation of Miss VINNIE REAM, paid a visit to the rotunda of the Capitol this morning, and was shown her statue of President LINCOLN. Members of the Press were informed of the exhibition, and many of them, and such members of Congress and other persons as happened to be about the Capitol at the time, witnessed the only exhibition of the work that will be permitted until the formal presentation to Congress. The reason that this special invitation was extended to the Secretary of the Interior, was that he was the officer appointed by the law giving MISS REAM the commission to carry it into effect. It is with him, as the agent of the Government, that the contract was made, and to him it must be formally fulfilled.

The statue is the size of life. It stands on a pedestal of lightly-clouded marble, which bears the simple inscription, ABRAHAM LINCOLN. Mr. LINCOLN is represented as standing with the right foot a little forward of the life, on which the weight of the body is thrown, bending slightly the right knee. A cloak, hanging loosely on the right shoulder has slipped from the left, till the hem reaches to the feet, and is held from slipping lower by the left hand, which falls by his side. The right hand is extended forward a few inches, and holds a roll, containing the emancipation proclamation. The head is bent forward and the look is downward, as if Mr. LINCOLN were speaking with a person of less stature than himself.

The expressions of those who saw the statue were unanimous in approval, and Miss REAM was warmly congratulated on the success which she had attained. In many instances, perhaps in most, the congratulations were from personal friends, and were the utterances of an earnest, kindly interest in the artist — for so she may truly be called — and the approbation expressed was not intended to be, and would not be, accepted as just criticism.

LINCOLN AS SUBJECT

Mr. LINCOLN is a subject presenting uncommon difficulties to the sculptor who attempts more than a bust, and difficulties impossible to overcome so as to conquer admiration. Realistic treatment is sure to displease those who, remembering only the beautiful, noble soul of the man, expect in the form which enshrined it gracefulness and beauty. On the other hand, GREENOUGH’S WASHINGTON is a lasting warning to those who would attempt the ideal. No statue of LINCOLN — and there are several — has met with general favor, and some of them, notably the Union Square, New York, have been favorite subjects of ridicule. And Miss REAM’s statue will undoubtedly receive more or less adverse criticism. It is a conscientious, painstaking, loving effort of a young woman, not devoid of artistic perception, and even genius to present Mr. LINCOLN as he actually appeared, and on the dress he habitually wore. He might have looked better clad in the Greek chalmys or the Roman toga. Probably the old Continental military uniform, the next favorite costume of the sculptor, would not have become him more. In either dress he would not have been Mr. LINCOLN. So if Miss REAM has not evoked from the marble a figure of striking beauty, so that she has fashioned truthfully the President, certainly it is not she who is in fault. The marble is a beautiful piece from Carrarra, and is almost entirely colorless.

MISS REAM’S SCULPTURE

It would be foolish adulation to pronounce the statue a great work of art, and probably Miss REAM would not thank any one for doting so. It may be or it may not be. The test of time will only determine that. But that it is a contribution of real value to the portraiture of its subject cannot be doubted. Houdon’s statue of WASHINGTON is not a great work except in its faithfulness; but for how much would the American people part with it. The giving of a commission of such importance to a young lady of only two years not very instructive experience in the study of art was possibly deserving of censure. But there will be few now found to express regret, or who will not be, indeed, glad. Not all the attempts of our Government to encourage and aid seeming artistic endowment, have found so worthy return.

HER VISIT TO EUROPE

VINNIE REAM went to Europe nearly two years ago, accompanied by her parents. her time was chiefly spent in Rome, though she traveled extensively on the Continent. She was in Paris three months. She did not content herself with simply executing the commission of the Government. An ideal work called “Sappho”of life size, and the “Spirit of the Carnival,” a girl throwing flowers, of half lifesize, were her first works while abroad, and they are now to be put in marble in Italy. Two of her earliest models she carried with her, and they are also being put in marble. Besides, at Paris, she modeled busts of DORK and Pere HYACINTHE; at Munich, HAULBACH, the celebrated German painter, who painted the famous Berlin frescoes; at Rome, LISTZ, and Cardinal ANTONELLI; at Vienna, JOHN JAY, and at London Mr. SPURGEON. These were all modeled from sittings by the different persons. From several of these personages MISS REAM has valuable souvenirs. ANTONELLI gave her among other things, a locket, with the head of Christ exquisitely cut in stone cameo. DORE presented her with a drawing on wood of one of his Bible pictures, “Judith.” She received kindly encouragement from the aged portrait-painter HEALY, Mr. STOKES, JOHN JAY, our Minister at Vienna, and others.

Miss REAM’s path has not been a pleasant one. What artist’s has? She has fairly earned her admittance into that fraternity, the struggles of whose members ought to make them all friends. Let her persevere: there is much in art for her to learn, and she can master it if she will esteem lightly what she has already attained, but, as of much greater consequence, what, to her own labor, the future will easily yield. J.E.C.

January 25, 1871

THE LINCOLN STATUE

Unveiling Miss Ream’s Statue of the Late Mr. Lincoln — Speeches by Prominent

Members of Congress

WASHINGTON, Jan.25 — The unveiling of Miss Reams’s statue of LINCOLN took place tonight, in the Rotunda of the Capitol, which was brilliantly illuminated and decorated with flags. One of them, made of California silk, was suspended over the statue. President Grant, Vice- President Colfax, Gen. Sherman, Judge Davis, the Committees on Public Buildings and Grounds, and the orators of the occasion occupied seats on the platform. There was a very large audience, including Judges of the Supreme Court and members of Congress, with their families. After music by the Marine Band, Senator Morrill, of Vermont, said that four years ago a little girl was employed in the Post office, at $600 a year, bus she had faith that she could do something better. Congress gave her an order to execute a statue of the late President LINCOLN. That statue and the artist were now before the spectators. Judge Davis of the Supreme court then, according to the program, proceeded slowly to unveil the statue, which was covered with the national flag. As soon as this was done the assembly broke forth in applause.

Senator Trumbull, of Illinois, in the course of his remarks, said that previous to the passage of the act by Congress giving to Miss Ream t he execution of this work, a number of persons had made statuettes and heads of LINCOLN, and she also made a bust from sittings by LINCOLN. This bore such a striking resemblance to LINCOLN that congress ordered from her a statue of life size. After giving a brief account of the artist and her personal history, and of her visit to Rome, he said she succeeded in procuring a block of marble without a stain — a fitting emblem of the pure character and spotless life of him the statue is intended to represent. Although LINCOLN was often seen in a happy frame of mind, there were periods with him of great depression, and melancholy seemed to have marked him for her own. When burdened with thought his countenance always had a pensive expression, and this was what the artist had endeavored to preserve in marble. Perhaps the highest compliment he could pay as he gazed upon the statue was the readiness to acclaim –“This is Mr. Lincoln” — others would judge of the execution of the artist.

General Banks commenced his remarks with the assertion that the incidents which distinguished the Presidential course of Mr. LINCOLN were greater than any which occurred since the foundation of the Government. Lincoln had greater capacities than those attached to ordinary men. He discharged his duties with such earnestness sincerity and success, as to enroll his name with the great civil administrators. The great cause of his success was the welfare of all men. In the very beginning of the war, at a time when party spirit ran high. LINCOLN was with difficulty prevented from making a visit to General McClellan in Maryland, by which he would have periled his safety.

It was not to embarrass the general with impracticable suggestions, but to give advice in relation to personal welfare. “I want McClellan to succeed,” he said, “for his success is our success.” Lincoln had no personal animosities. Those who differed from him were not necessarily estranged from him. He always counted on reconciliation. It was this quality that drew to him the hearts of all classes of the people. It was just that his figure of enduring marble should be placed in he Capitol to remind us and our successors of the virtue, character, success and devotion to the principles which be advocated and defended and died in maintaining.

Representative Brooks, of New York, said: It was appropriate that, in unveiling a statue like this, a Democrat should be given an opportunity to express for himself and associates their common interest both in the map and in the monument — the memorial of the man. He who acted so foremost a part as Mr. LINCOLN in that portion of our history — the most exciting and most perilous, save that of our revolutionary era — is entitled, not only to such a memorial as this, but to have it placed here under the great dome of its Capitol. We have no Parthenon, no Pantheon, no Vatican, no Pinakothek nor no Westminster Abbey, wherein to entomb our illustrious men or to erect statues to their honor. Yet the time is coming, nay, it is in part come, when this Rotunda, and the surrounding halls and grounds, will be filled with pictures, paintings, frescoes, statuary, bronzes, friezes, bas reliefs, and other monuments of the world’s memorable men. But the work here that we are unveiling is the double memorial of not only a Chief Magistrate in the prime of life, foully shot down, but the memorial of a woman’s handwork — a woman’s plasticart. The Parthenon, the Vatican, the great museums of Paris, London, and Berlin bring over to our eyes the works of some Phidias or Praxiteles of antiquity, but they show us no marble monuments, busts or statues the finger work of the fairer sex, while here in this Rotunda we now see the equal rights of woman, if not with the ballot, with the pencil, to chisel, the artistic instruments, to perpetuate the human form divine. Fortunate the man thus sculptured! Fortunate even in the calamities of his country, for in a restored Union he lived to survive them all, fortunate in the trying hours of his death as he is thus forever consecrated to the Republic by his martyrdom, immortalized among all mankind; fortunate, too, on being thus handed down to posterity by a woman’s love of a noble art, one of the few immortal names that were not born to die.

Senator Carpenter, of Wisconsin, said that, passing by the artists of world wide fame, Congress employed a young girl to execute the statue. The selection of the artist was most fortunate. Sculptors, generally, patterned after ancient models, their productions resembling neither men nor gods; and, as an illustration, he referred to Greenought statue of Washington in the East Capitol grounds, it having been compared to an Englishman just from the bath. It looked no more like Washington than a prize-fighter. Art had completely triumphed over nature. He spoke of the freedom of the West, which was not trammeled by the education of the foreign schools, and claimed for the address of Mr. Lincoln at the dedication of the Gettysburg Cemetery, greater eloquence than the oration of Edward Everett. He eulogized the Western artist for having given to the country a true representation of Lincoln. The statue was satisfactory. Judge Davis, for many years the personal friend of Mr. Lincoln, authorized him to say so. To the fascinating, dark eyed damsel, he expressed his own and the thanks of the people of Wisconsin. To the President, Vice President, the Judges of the Supreme Court, the heads of Departments, the high official officers, military and naval heroes, the matrons and belles and beauties of the audience, he now presented the artist, Miss Ream.

This lady, as the Senator uttered the concluding words, stepped upon the platform, bowed and retired followed by the applause of the assemble.

The crowd lingered some time in the Rotunda examining the statue. A number of colored persons availed themselves of the same opportunity.

Music by the Marine Band concluded the exercises.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard