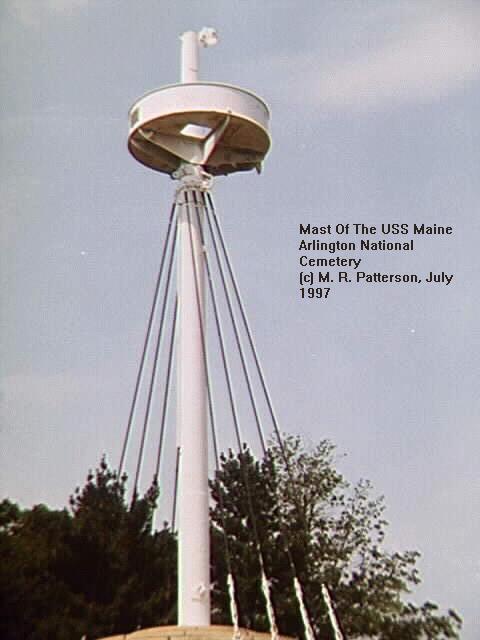

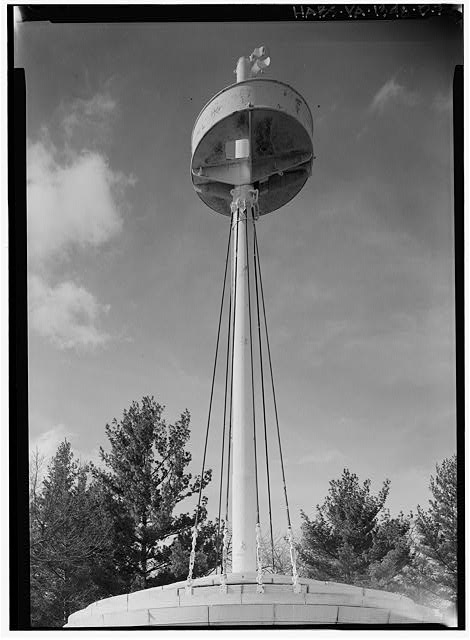

The mast of the U.S.S. Maine was removed from the ship in 1905 shortly before the ship was taken out to sea and sunk with military honors. The mast was then installed above a memorial in Arlington National Cemetery in honor of those who lost their lives when the ship sank in Havana, Cuba, Harbor in 1898. This sinking was the event that started off the Spanish-American War.

USS Maine Memorial

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington County

Arlington, Virginia

HABS No.: VA-1348-D

CAD Measured Drawings, Written History and Large-format Photography (1999)

The sinking of the battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor on 15 February 1898 was the seminal event leading to the Spanish-American War. Although the cause of the explosion (whether a Spanish torpedo or an internal mechanical malfunction) has never been definitively determined, the event enraged American public opinion, and on 19 April Congress declared war on Spain. The Spanish forces were defeated with relative ease, and the United States eventually acquired Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines as colonies.

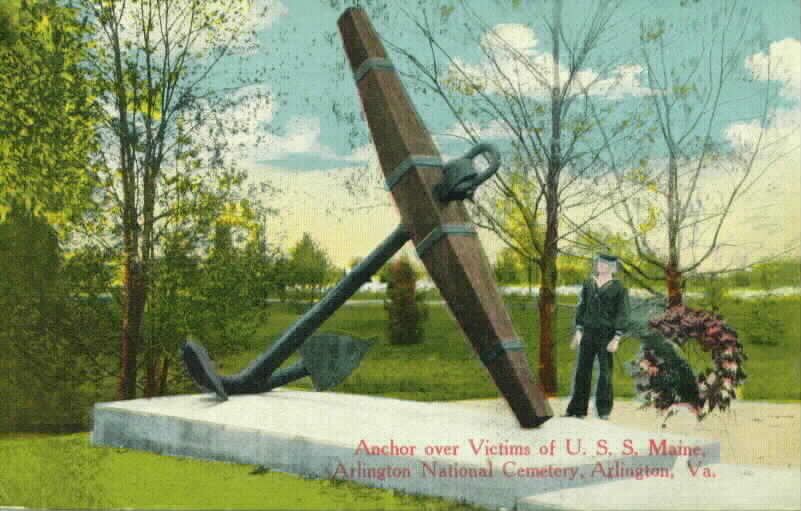

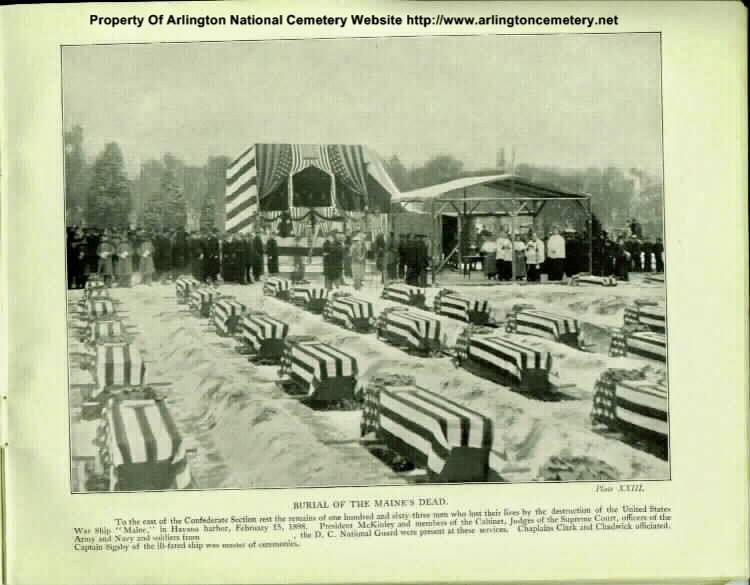

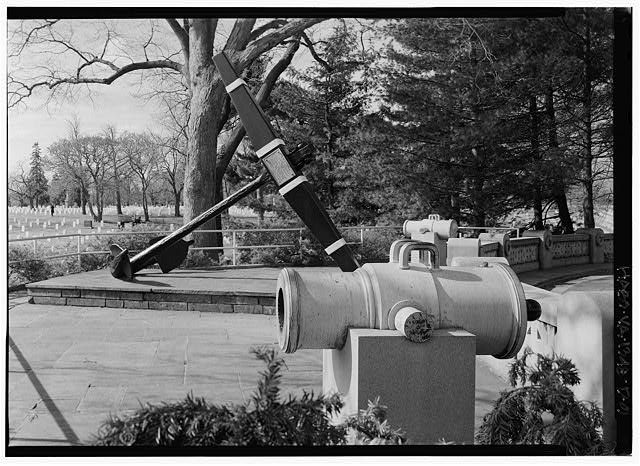

In late 1899 the remains of 163 of the sailors and marines who died in the explosion were removed from the semi-submerged ship. They were laid to rest with solemn ceremony in their own section of Arlington National Cemetery on 28 December of that year. An anchor from a similar battleship, and two flanking 18th century Spanish mortars brought back from Manila by Admiral Dewey, were installed as the first memorial to the victims of the USS Maine.

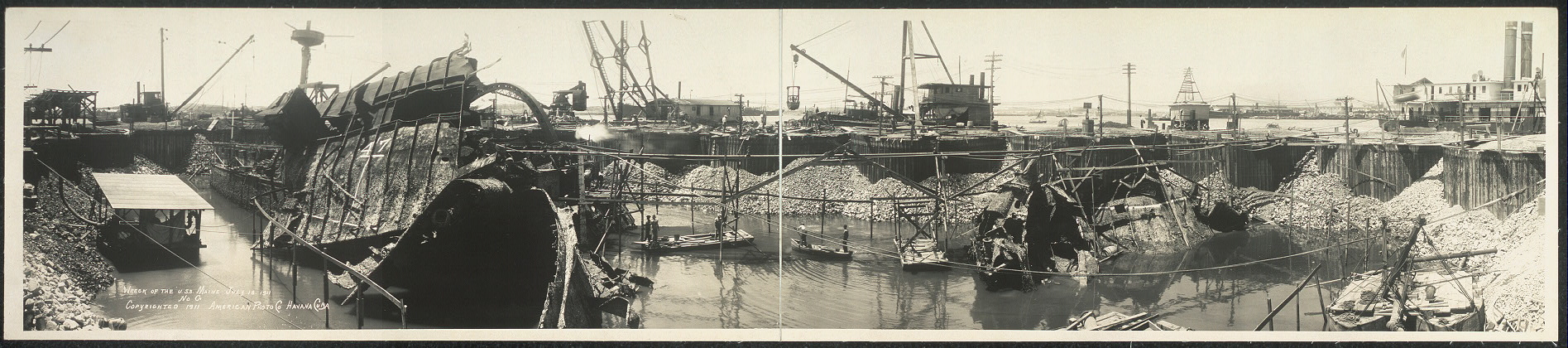

The ruins of the battleship remained in Havana harbor for another decade. Finally, bowing to both American and Cuban public pressure, the Navy built cofferdams around the ship to re-examine the ruins and to remove the remaining human remains, before towing the ship out to sea and scuttling it in 1912. During this time, the ship’s main mast was removed and brought to Arlington to form part of a larger memorial, to be located adjacent to the interred sailors and marines. A design competition for the USS Maine Memorial was held in 1912. The results, however, were deemed unsatisfactory, and the Commission of Fine Arts subsequently commissioned prominent Washington architect Nathan C. Wyeth to design the memorial.

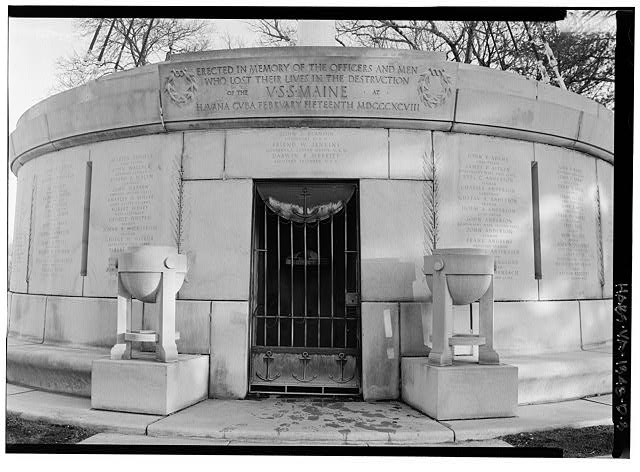

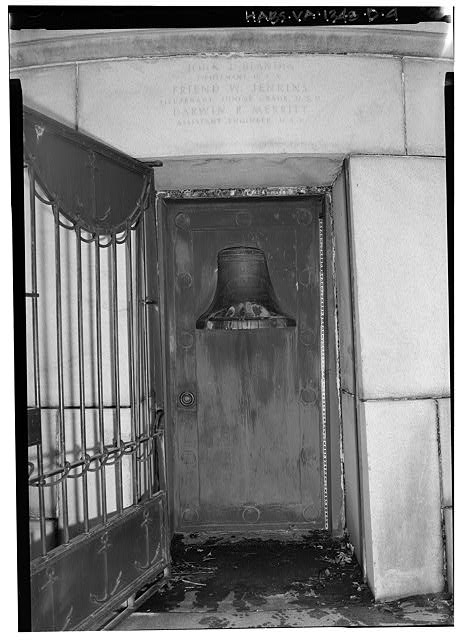

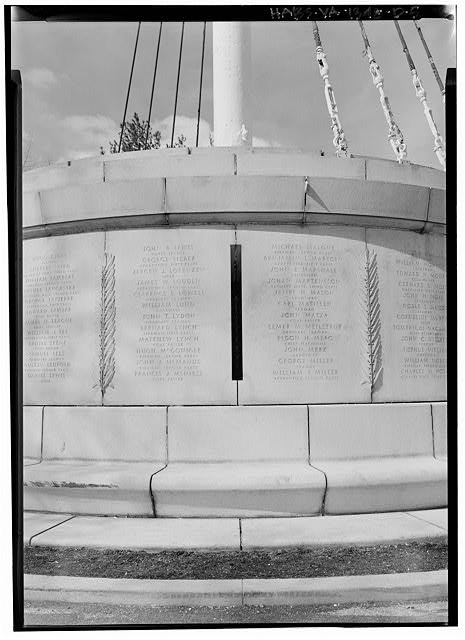

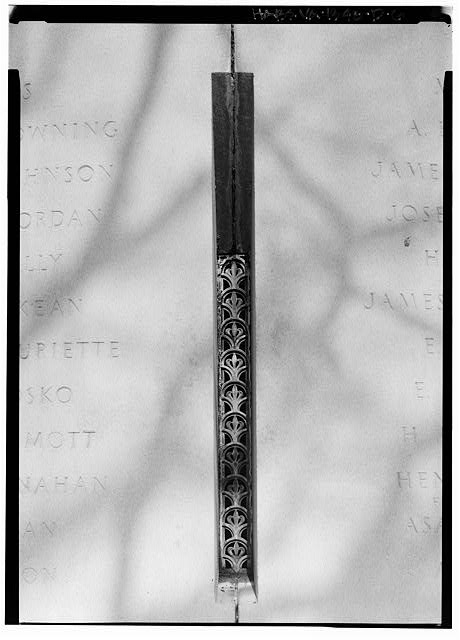

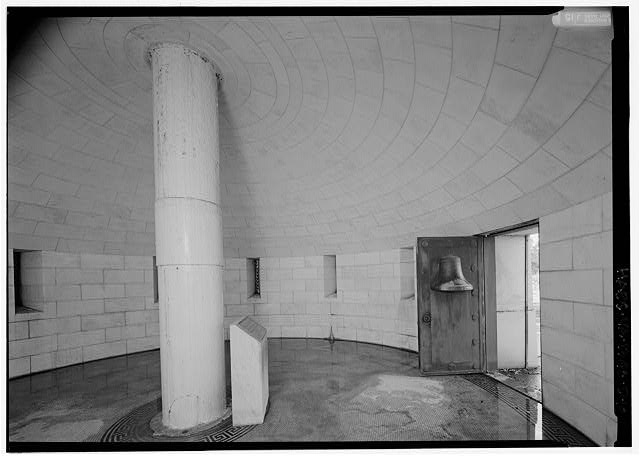

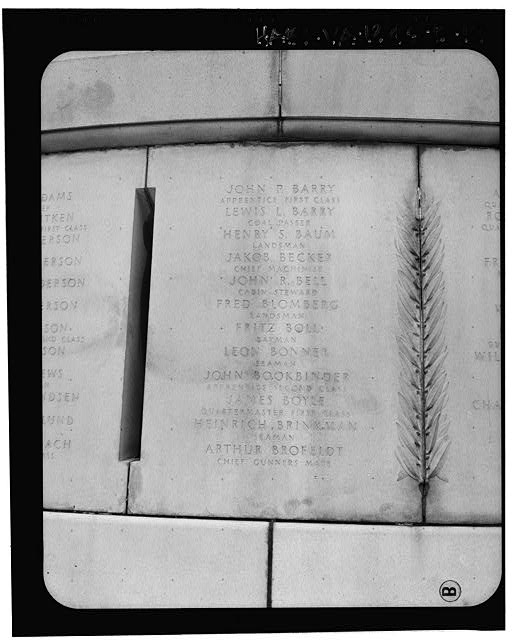

The memorial, as designed by Wyeth and dedicated in 1913, is in the form of a circular, stylized turret, serving as the base for the mast. Constructed of concrete, it is sheathed on the interior by marble, and on the exterior by granite. 23 panels on the exterior list the names and occupations of the 264 sailors and marines who perished when the ship sank. Stylized granite Roman tripods flank the entrance. A fragment of the ship’s bell is attached to the massive bronze door. The nautical theme is reinforced by the use of metal rope and emblematic anchors on the bronze entrance gate. Bronze grills fill the 11 slit windows. The interior ceiling is in the form of a shallow saucer dome, and the floor is of mosaic tile. The entire memorial is flanked by two granite balustrades across the circumferential road surrounding the structure.

The USS Maine Memorial acquired additional historical significance by serving as the temporary resting place for the remains of Ignace Jan Paderewski, noted Polish patriot and internationally renowned concert pianist, from 1941-92. In 1962, a terrace paved with bluestone flagging was constructed for the anchor and mortars.

Documentation of the USS Maine Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery was undertaken by the Historic American Buildings Survey / Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) division of the National Park Service, E. Blaine Cliver, Chief. The project was sponsored by the US Department of the Navy, Richard L. Hayes, NAVFACHQ Chief Historic Architect; and by the US Army Corps of Engineers, Technical Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings, Horace Foxall, Jr., Manager. Project planning was coordinated by Paul Dolinsky, Chief, HABS; by Catherine C. Lavoie, HABS Historian; and by Joseph Bunton, Engineer, Arlington National Cemetery. The field work was undertaken and the drawings were produced by HABS Architects Mark Schara and Raul Vazquez. Assistance in the production of the drawings was provided by Architecture Technician Brian J. Bitner (Catholic University of America). The historical report was written by HABS Historian Virginia B. Price. The large format photography was produced by HABS Photographer Jack E. Boucher.

In Remembrance of the USS Maine Observance Marks Anniversary of Sinking

By Steve Vogel Washington Post Staff Writer Monday, February 16, 1998

“Remember the Maine,” the rallying cry that led the United States into a war with Spain, was intoned once again yesterday as more than a hundred gathered to mark the 100th anniversary of the ship’s sinking in Havana harbor.

This time, the words were a mournful cry in memory of the 266 American sailors and Marines who perished in the explosion and sinking.

Yesterday, beneath a bright blue sky, Secretary of the Navy John H. Dalton and descendants of the ship’s crew members walked to a hilltop in Arlington National Cemetery where the mast of the sunken ship is the centerpiece of the USS Maine Memorial. The name of each victim is etched on the stone of the memorial. The graves of 228 Maine crew members are nearby.

“We are gathered at a location which few Americans even know exists,” retired Rear Admiral Morton E. Toole said. “But in its day, this was as sacred as the Vietnam Memorial wall is today.”

The USS Maine, bristling with heavy guns that made it one of the premier battleships in the Navy, was dispatched to Cuba in January 1898, ostensibly on a goodwill visit. But it was also to protect Americans on the island in the wake of increased friction between the United States and Spain. Cuba, then part of the Spanish empire, had been the scene of some insurgency by Cuban rebels.

On February 15, 1898, at 9:41 p.m., as the 319-foot-long Maine lay moored in the harbor, Havana was illuminated by a burst of bright light. The Maine was shattered by a prolonged explosion that sent debris into the air and filled the sky with black smoke. Less than one-fourth of the 350 crew members on board survived the explosion; the rest were blown apart, crushed, drowned or suffocated.

Public opinion fixed blame for the explosion on Spain, and “Remember the Maine” soon became the cry of American newspapers, particularly William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. The United States declared war on Spain in April 1898. American victories in Cuba and the Philippines marked the emergence of the United States as a world power.

But there were always doubts that the sinking of the Maine was anything but an accident. An inquiry ordered by Admiral Hyman Rickover and conducted by historians and engineers in the mid-1970s concluded that a mine or torpedo could not have been responsible for the blast. The likely cause was a coal bunker fire that ignited the ship’s magazine. Some still insist that the Maine was a victim of sabotage.

Speakers at yesterday’s ceremonies said the debate is no longer relevant. “It makes no difference whether the explosion was caused internally by coal or externally by a mine,” Toole said. “The fact is 266 Americans died.”

Wreaths were placed on three of the graves surrounding the USS Maine Memorial. One was laid on the grave of Sergeant James T. Brown, the senior Marine killed on the battleship; the second on the grave of Chief Yeoman James M. League, an Annapolis native; and the third on a joint grave that holds the remains of four unknown victims. Thirty-two descendants of League’s, most of whom still live in Maryland, were among those who attended the ceremony. “We usually have a reunion every year, but this is the first time we’ve all assembled to come to the memorial,” said Patsy Mills, 67, who retired as secretary of the Somerset County Board and is one of League’s great-granddaughters.

“My grandmother always talked about him, how he was a warrant officer and they found him in his bunk,” Mills said. “When we were little, my parents always brought us to this monument, to see all the names.”

Margaret Daly, 81, a granddaughter of Brown’s who lives in New York City, dabbed her eyes with a tissue after helping lay a wreath on her grandfather’s grave. “A lot of people don’t even know what it’s all about,” Daly said.

Cubans Remember The USS Maine Explosion

February 7, 1998 – The Associated Press

HAVANA (AP) — The lightning and thunder of a huge explosion ripped through the still darkness, shattering windows, knocking doors off hinges, sending the panicked people of Havana streaming down toward the waterfront.

After the echoes died, the destruction of the USS Maine that February night did one more thing as well: It propelled a new player, an assertive America, onto the road to global power.

Today, 100 years later, the oily black waters of Havana harbor ebb and flow over the spot where the U.S. battleship exploded and sank, claiming the lives of 267 crewmen. Tiny ferries chug past, as they did then. Rusting old freighters ride at anchor.

And just as on the moonless night of Feb. 15, 1898, dark suspicions and uncertainties still cling to the Maine.

At Havana’s City Museum, Nora Benitez, a custodian of photographs, equipment and other artifacts of the Maine, sets out the standard Cuban view: That the warship was destroyed in a cold-blooded American conspiracy.

“The United States was behind the explosion,” she insists. “We’ve always known it was a pretext the United States used to intervene in Cuba.”

A Cuban naval historian, Gustavo Placer Cervera, more in touch with technical analyses of what happened that night, subscribes to the “Rickover report” — the conclusion that the Maine explosion was probably an accident, not sabotage.

But what’s more important, says the retired navy commander, is that the U.S. government “manipulated and used the explosion. … The key fact is that the war was prepared in advance.”

The mystery of the Maine, spark to the Spanish-American War, reaches back to the 19th century. But on this 100th anniversary it’s clear it will feed mistrust between nations well into the 21st.

——

When the 319-foot-long warship, armed with 10-inch guns, sailed into Havana harbor on January 25, 1898, it was an unwelcome guest.

Spanish colonial authorities had been notified of its “friendly” visit only hours before. But trying to block it would have been dangerously provocative. Relations were bad enough between Madrid and Washington.

The U.S. government was pressuring Spain to pull out of Cuba, where guerrillas were fighting an independence war. Americans were outraged at Spanish atrocities. Some in Washington — and Cuba — favored U.S. annexation of the sugar island.

President William McKinley ordered the battleship to Havana to intimidate hard-liners in the Spanish military who were resisting Spain’s autonomy plan for Cuba. These officers were furious. Ashore in Havana, the Maine’s captain, Charles D. Sigsbee, was handed an anti-American leaflet on which someone had scrawled, “Watch out for your ship!”

On Feb. 15, most of the 328 enlisted crewmen retired after 9 p.m. to their hammocks in the forward quarters. Twenty-two officers were in aft cabins or at their posts.

At 9:40 p.m., those in the rear felt and then heard the explosion, a “bursting, rending and crashing roar,” as Sigsbee later called it. It was tremendous — experts estimated 10,000 to 20,000 pounds of powder in forward ammunition magazines blew up.

Towering flames shot into the sky, along with bits of metal deck, guns, men and pieces of men. The forward third of the ship was transformed into mangled, sunken wreckage. The aft settled to the muddy bottom.

Back in America, a sensationalist press decided a Spanish mine had destroyed the ship — even though Spain wanted to avoid war at all costs. “The Warship Maine Was Split In Two By An Enemy’s Secret Infernal Machine!” the New York Journal screamed.

The U.S. Navy was not so sure

It convened a court of inquiry in Havana, four officers who relied on what the Maine’s officers and Navy divers, working in primitive helmets in the inky murk, could tell them.

The court focused on the hull’s steel keel, bent upward in an inverted “V.” Its report, on March 21, 1898, concluded there were two explosions: The explosion of a mine beneath the hull that blew the keel upward, and the resulting detonation of the powder stored above.

It said it had no evidence fixing responsibility. But for America’s yellow press and congressional jingoes, there was no question it was the “perfidious” Spaniards. “Remember the Maine!” was the slogan on millions of American lips, emblazoned across shop windows, sung by children, printed on candies and women’s hair ribbons.

By late April, U.S. forces were at war with Spain, and in just three months they seized the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico. America, suddenly, was an Asian and Caribbean colonial power.

Cuban rebels, believing they were near victory and fearing U.S. annexation, had not wanted American intervention. Now an independent Cuba came under U.S. domination, in a relationship that didn’t end until Fidel Castro’s revolution six decades later.

In 1911, because the sunken Maine was a navigation hazard, and 70 men’s remains were still trapped in the hulk, U.S. military engineers built a cofferdam around the wreck, water was pumped out, remains were recovered, and the rear two-thirds of the ship was refloated, towed to sea and sunk again.

The “dewatering” allowed the Navy to photograph the wreckage in detail, and a new court of inquiry was convened. It rejected the 1898 finding on the inverted “V,” saying that was caused by the internal explosion. Instead, it focused on a hull bottom plate bent inward — damaged, the court held, by an exploding external mine.

So the record stood for decades, until U.S. Adm. Hyman G. Rickover, “father of the nuclear Navy,” took an interest and put experts to work on the Maine case, using more sophisticated analysis of the old photos.

Their 1976 report concluded the explosion was almost certainly caused by spontaneous combustion of coal in a bunker abutting a powder magazine. Such coal fires were commonplace in that day. They said a mine would have caused more damage to the inward-bent plate.

But they acknowledged, “A simple explanation is not to be found.”

In 1995, Smithsonian Institution Press published a book, “Remembering the Maine,” by Peggy and Harold Samuels, pointing up flaws in the Rickover analysis and concluding that Spanish fanatics had set off a mine. It cited no new hard evidence, but uncorroborated reports of the time about plots against the ship.

In Spain, opinion is also divided. The Spanish navy approvingly reprinted the Rickover study, but a Spanish historical journal has pointed a finger at Cuban saboteurs.

Most recently, the National Geographic Society commissioned a computer modeling study of the coal-fire and mine theories, and found both feasible. “The case remains open,” National Geographic says in its February issue.

——

The 40-foot-high columns of Havana’s Maine Monument rise forlornly over the Malecon, the city’s seaside boulevard. Broken beer bottles litter its derelict fountain.

The pedestal on top has been bare since Castroites pulled down the “arrogant” American eagle in 1961. A new plaque describes the dead sailors as victims of “imperialist greed in its effort to take over the island of Cuba.”

“They pretended that intervention on behalf of Cuba was a big deal, but it was just to take over Cuba’s resources,” said Benitez, the City Museum curator.

Rickover, who died in 1986, concluded that with better investigative work in 1898, “war might have been avoided.” Placer is not so sure.

The Havana scholar has labored long hours meticulously reviewing century-old U.S. Navy orders and U.S. diplomatic messages. He says the war plans, the inertia, all were headed toward collision with Spain.

“The explosion of the Maine only accelerated things,” he said.

And what happened that windless tropical night 100 Februarys ago? When we remember the Maine, what are we remembering?

“We’ll never know,” the Cuban historian said. “All we have are hypotheses. We cannot prove them. We will never prove them.”

By Eugene L. Meyer Washington Post Staff Writer Friday, June 12, 1998

Remember the Maine? No? What about Capt. Charles D. Sigsbee? Or Lt. Richmond Pearson Hobson? Well, then, how about the Hero of Manila, Admiral George Dewey? You remember: the man who uttered the immortal words, “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.” Still clueless? Well, surely the Rough Riders ring a bell. You know, Teddy Roosevelt and the Battle of San Juan Hill?

For the historically impaired, it was, in Secretary of State John Hay’s phrase, “a splendid little war” that incidentally transformed America into an imperial world power. But 100 years after it happened, who now remembers the Spanish-American War? There’s nothing approaching the huzzahs and hoopla of the Civil War centennial or even the somber remembrance occasioned by the 50th year anniversaries of World War II.

There are no veterans left to remind us — the last died in 1992, at age 106 — and Spanish-American War reenactments resonate in, shall we say, a very low key.

And yet, the war that marked, as a contemporary book title put it, “The Passing of Spain and the Ascendency of America,” is still much with us:

A century later, our war-won “possessions” nag: Puerto Ricans clamor for statehood, Guamanians for commonwealth status. Cuba, on its own since 1902, remains problematic. Beyond the geo-political issues these territories raise, tangible if largely uncharted reminders of the conflict can be found in and around the Washington area.

From Washington National Cathedral to the Washington Navy Yard to Arlington National Cemetery and Annapolis are monuments, memorials, artifacts and ghosts of the Spanish-American War. A mere two hours north, the cruiser from which Dewey directed the destruction of the Spanish fleet sits docked on the Delaware River, the only surviving ship of America’s all-steel “New Navy” of the 1880s and 1890s.

How did America find itself in this now all-but-forgotten conflict? Having fulfilled its Manifest Destiny to span the North American continent, the United States was hankering to expand beyond its borders and the Spanish empire loomed large and vulnerable. Spain had staked its global claims in the early 1500s. Though Spain had lost its Central and South American colonies, it still possessed the Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico and — just 90 miles from Key West — Cuba. Cuban insurrectos were challenging Spain’s colonial rule; Imperial Spain had decided to crack down.

All that was needed was a spark. That would be the Maine, and the incendiary “yellow press” — waging its own war of circulation in the newspapers of Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst — would further help inflame the situation.

The shooting war that swept away what remained of the Spanish empire lasted just a bit longer than the Gulf War. When the smoke cleared, the United States was in possession of most of Spain’s territory and the American Century had dawned.

Many events of that watershed time are worth recalling. But first, remember the Maine!

The ship had been anchored three weeks in Havana Harbor, supposedly to safeguard American interests while Spanish colonialists and Cuban revolutionaries duked it out, when the big blast occurred on Feb. 15, 1898. Historians to this day differ on whether an accidental shipboard ignition or a Spanish mine caused the USS Maine to explode and sink. Regardless, “Remember the Maine!” became an emotional battle cry that propelled us into war with Spain three months later, and to victory shortly thereafter.

The explosion seemingly blasted the ship’s pieces and contents far, far beyond the Caribbean island, since fragments and artifacts appear in so many museums in so many geographically dispersed locales. And in a sense, the explosion did have a rather tornadic impact.

The Maine itself was raised from Havana Harbor in 1912, its foremast removed to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, its mainmast to Arlington National Cemetery, where 229 crew members were reburied with much pomp. Last month, on Memorial Day, a service was held there, attended by the Spanish ambassador and an American general of Hispanic heritage. The U.S. Army band played, attracting a few tourists, and fresh wreaths were laid. The crowd was small. No American media covered the event.

The Maine monument, mainmast and graves of the crewmen are all located on or near Sigsbee Drive, named for the ship’s captain. When John C. Metzler Jr., superintendent of Arlington National Cemetery, leads tours, he says, “I always make a reference to the Maine and its importance.” But when he, once, raised his fist and proclaimed “Remember the Maine!” he got no response. End of shtick.

I visited the cemetery on a drizzly gray day. In search of specific graves, I was able to obtain a pass that allowed me to drive my car into the grounds. I wended my way around Schley Drive, named for Rear Adm. Winfield Scott Schley, of Frederick, Md., largely credited with the naval victory at Santiago, Cuba, and buried in Section 6.

I searched for Schley’s grave, and also for that of Hobson, finding neither, though I did find Hobson Drive and Hobson’s Gate, named for the young naval officer elevated to hero status after his capture by the Spanish at Santiago.

But, serendipitously, I stumbled onto the obelisk memorial to “Fighting Joe” Wheeler, an old Confederate general recommissioned to fight in Cuba and remembered here as “soldier, statesman, gentlest, tenderest and most lovable of men.” Wheeler’s grave is just below the Custis-Lee House, with a sweeping view of monumental Washington.

Further up the hill, I noted a monument to little-known Brig. Gen. Theodore J. Wint (1845-1907), a veteran of the Civil War, Indian Frontier (1866 to 1888), Cuba (1898), China (1900-1901), the Philippines (1901-1904) and the Army of Cuban Pacification (1906-1907). Here was a man, I thought, whose career encompassed a good deal of American martial history, a 20th-century link to the past — and a Spanish-American War veteran to boot.

It’s harder to miss the Maine’s mast on Sigsbee Drive, near the much more visited Tomb of the Unknowns. In the same vicinity looms another monument to “the Soldiers and Sailors of the U.S. who gave their lives for their country in the war of 1898-9 with Spain.” (For the record, only 379 Americans died in battle, ten times as many succumbed to disease, and another 1,415 were wounded. On the other side, 2,312 Spanish were killed in battle, 3,260 wounded.)

There are other Spanish-American War monuments in these parts: to the nurses who served in the war, to the famed Rough Riders, officially the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry. Leonard Wood, commander of the unit in which Teddy Roosevelt held a lower rank but a higher profile, is buried here. So is Rear Adm. William T. Sampson, who drew up the naval battle plan used to defeat the Spanish at Santiago but received little of the credit.

And, of course, there are rows of small headstones, marking the graves of those who served and survived but ultimately were buried here. The common soldier is also memorialized in a statue known as “The Hiker” on Memorial Drive, just outside the cemetery. The statue of a soldier wearing a Spanish-American War uniform and holding a rifle in both hands was erected as recently as 1965. It just looks older.

If the USS Maine represented a humiliation that propelled America into war, the USS Olympia — Admiral Dewey’s flagship at Manila — symbolized American triumph and vindication, the utter destruction of the Spanish fleet in just a few hours on May 1, 1898. Items from both the Maine and the Olympia are on display at the Washington Navy Yard, in a museum housed in a former breech mechanism shop. The 1898 conflict covers but a small section within the cavernous building, but it’s hard to miss.

Here’s a silver tray used in the wardroom of the Maine, and a commemorative spoon with “Sigsbee” on the handle and the Maine in the bowl. Here are views of Admiral Dewey, he of the thinning white hair and bushy white mustache, on the deck of the Olympia. In another display case, there are Dewey’s cocked hat, dress coat, pants and shoes and the pennant that flew from the Olympia. Here, too, for local history buffs of the war, is a scroll of 93 volunteers from Washington, mustered in May 17, 1898, mustered out almost six months to the day, with just one fatality.

The Navy Yard, it turns out, was where the Olympia ended her final mission on Nov. 9, 1921, bringing with her a casket from France containing the Unknown Soldier. The ship wound up in Philadelphia and, thanks to the efforts of private citizens, was never sold for scrap with the rest of the fleet. There it sits today, docked on the Delaware River waterfront.

I’d first seen her in 1966, as a young reporter assigned to do lots of cheap fun Philadelphia things for a week. Boarding cost 50 cents then, $5 today. It’s still a cheap thrill. The ship shares its berth with a World War II submarine, which must be crossed to reach her. The duo are now part of the adjacent Independence Seaport Museum, dedicated to “exploring America’s maritime heritage.”

The Olympia, with a fresh exterior paint job but with no ballast, was listing slightly to port when I boarded. Remarkably, tourists pretty well have the run of the 106-year old ship, which is 344 feet long and 53 feet wide. I wandered the lower and upper decks alone before meeting up with Tim Hastings, a 32-year-old former naval officer who is the ship’s curator.

The Olympia’s not in such great shape, he told me. It needs a $5 million overhaul to replace the steel and otherwise make her, as they say, shipshape. But it’s still a sight to see. Even if none of its guns are original, there is much that is, or close to it.

The main deck exhibits what Hastings calls “cutting edge 1890s technology” in a refrigerator that used compressed air. And there’s the galley, last “modernized” in 1902. There’s Dewey’s pantry, bathroom and cabin, and bookcases he had made in the Philippines. Throughout are display cases full of Dewey memorabilia. After the war, Dewey was awarded a mere $9,570 for defeating the Spanish squadron at Manila. How much richer he might have been if he’d simply invested in souvenir spoons, or been compensated for his image on a displayed box of Hershey chocolate cigars.

The selling of the war goes on, of course, in the Independence Seaport Museum gift shop. There, $18.99 gets you an Olympia cap, $15 a nice poster of the ship at sea, $9 an 8-by-10 photo, $6 a coffee mug, $4.99 a hot plate, $3.99 a commemorative license plate, $2.99 an ashtray. My favorite, however, for a mere $19.99, is a medal made from the propeller of the Olympia, inscribed with the date of May 1, 1898 and the words that by now you must surely remember: “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.”

I found no such inscription anywhere in Arlington National Cemetery, where there’s Dewey Drive, but no Admiral Dewey. The Hero of Manila was buried there in 1917, but his wife moved his remains in 1925 to Washington National Cathedral.

There he is buried under the Bethlehem Chapel, the first part of the edifice to be constructed upon his motion in 1910 as a Cathedral board member. On the north side of the chapel is a cenotaph with four stars, his name, vital dates and highest rank: Admiral of the Navy. Two flags fly over it: a four-star flag, and the Stars and Stripes. Nearby, there’s a memorial plaque for his younger son, A. Peter Dewey, a paratrooper killed in action in China in 1945.

Not on any tour but prominent in a circle between the Cathedral and St. Albans School for Boys is the Peace Cross “raised in the Historic Year A.D. 1898,” according to the inscription, “that it may please Thee to give to all Nations Unity, Peace and Concord ” A 1922 guide notes that the cross was raised to mark the Cathedral’s beginnings “and as a memorial of peace with Spain. Before the Cross the fair city is spread out, the Capitol being the central point of vision in the distance.” From this height, I could more clearly see the Washington Monument, and even Arlington beyond.

The grounds of the Naval Academy in Annapolis are also monumental, and it was here that George Dewey graduated in 1858, perfectly in time to see service in the Civil War. With naval action dominating the Spanish-American War, it’s not surprising that almost all of its heroes were graduates of the Academy. What is surprising is that, in this centennial year, so little has been done there to remember them.

This is through no fault of James W. Cheevers, curator of the Naval Academy Museum, who has mounted a splendid exhibit on the conflict inside Preble Hall.

“I hoped the visitor center would run special tours,” he said, “at least on Feb. 15, May 1 and July 3,” anniversaries of the Maine’s sinking, and the battles of Manila Bay and Santiago, respectively. In the flush of victory, Congress had appropriated $1 million to rebuild the Academy. “It was such a popular little war in our history, the first in which all the top naval leaders were Naval Academy graduates.”

But in Annapolis, this year, the Maine was forgotten, and on May 1, the frenzy over the arrival and departure of the Whitbread around-the-world sailboat race totally eclipsed the anniversary date of Dewey’s triumph.

No matter. Cheevers has prepared a list of “significant historic items” located at the Naval Academy. These include the foremast of the Maine; two guns from the Spanish ship Vizcaya, captured in the Battle of Manila; anchors from the USS New York, the flagship of Rear Adm. Sampson in the Battle of Santiago, and a Sampson memorial window by Louis C. Tiffany; a memorial list of alumni killed in the war; plaques and portraits; and the stern and bow ornaments of the USS Olympia.

From 1912 to 1957, the Reina Mercedes, a Spanish vessel captured at Santiago, was moored at the Academy. It was then scrapped, as were other historic vessels of the period, for cash. It lives on, in a way. Recently, the new enlisted barrack at Naval Station, Annapolis, across the Severn River, was given its name.

Following Cheevers’s list, you could consume more than a day gazing at portraits, plaques and the like (consider, for instance, that the chapel’s cornerstone was laid by Dewey; few do). But with so many choices, one must set priorities.

The museum exhibit is a must. It has six paintings of the USS Maine alone, a life preserver, two porthole covers, a log glass, keys to the magazines, an electric light shade and bulb, and a bugle — all from the ship. It even has an 1888 penny from Capt. Sigsbee’s desk, his ship’s inkwell and binoculars.

It has four paintings of the Battle of Manila Bay, and what are said to be the first shells shot during both the battles of Manila and Santiago bays. It has a set of 12 commemorative spoons, magazine covers of Dewey (including one with his dog), 16 postcards of naval ships, famous front pages, sheet music, ship models large and small, and more Dewey mementoes, including a plate with his famous “fire when ready” command to you know whom.

During the windup to Whitbread, I’d noted in the Naval Academy’s Armel-Leftwich Visitors Center a smaller display of Spanish-American War items. It was gone now, and a docent at the information desk could provide no information. But I knew where to go.

I walked outside and along the Annapolis harbor seawall to Trident Point, where the Maine’s foremast rises at water’s edge, its foretop still twisted from the explosion. “Ship blown up Havana Harbor 15 Feb. 1898,” the small plaque asserts conclusively. “Mast recovered 6 Oct. 1910. Erected here 5 May 1913.” I thought about what a big deal that must have been, back then, and how unattended the site is today. But not completely unremarked. As I stood there, I could hear a recording blaring from a loudspeaker on a tour boat, the Harbor Queen, revealing to the tourists the identity of a curious-looking tower on shore.

On my way out of the Academy yard, I paused at the 5.5-inch diameter gun seized from the Vizcaya on July 3, 1898, its long green barrel all but buried in a grove of trees. I never did find its companion, though Cheevers assured me it is nearby.

Exiting the Academy onto Maryland Avenue, I asked the Marine guard at Gate 3 if he knew its whereabouts. “Sorry, sir. I haven’t really heard anything about the gun,” he said.

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY — On the cemetery grounds are the mainmast from and a monument to the USS Maine, a monument to all American forces in the war, monuments to Spanish-American War nurses, the Rough Riders and numerous military figures prominent in the conflict. “The Hiker” is a 1965 statue, opposite the Seabees monument, on Memorial Drive just outside the cemetery. The Arlington Cemetery Metro station is a short walk from the Visitors Center. There is also paid parking, but the first 30 minutes are free if the ticket is stamped at the Visitors Center. Those wishing to visit specific grave sites may obtain a vehicle pass that allows you to drive and park your car inside the cemetery. Otherwise, for $4.75, you can ride a Tourmobile, getting off and on at will, throughout the cemetery. Open 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. April through September, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. October through March. 703/695-3250. (“Arlington National Cemetery: Shrine to America’s Heroes” [Woodbine Press, 1986], by James Edwards Peters, is an excellent guide to Spanish-American War and other monuments, memorials and grave sites at Arlington. It’s for sale at the Visitors Center for $13.95.)

THE NEWSEUM — This museum’s News History Gallery contains a section on the role of journalism in promoting the Spanish-American War. Displayed are front pages that played up the Maine disaster and mongered for war. 1101 Wilson Blvd., Rosslyn (Metro: Rosslyn). The Newseum is free and open Wednesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. 703/284-3544.

WASHINGTON NAVY YARD — There’s a Spanish-American War exhibit in the Navy Museum, within the former breech mechanism shop of the Naval Gun Factory. 901 M St. SE. Open weekdays 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. from Memorial Day through Labor Day, weekdays 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. the rest of the year, and 10 a.m to 5 p.m. weekends and holidays. Free admission and parking. 202/433-4882. On the grounds in Leutze Park are a number of captured bronze ordnance, including some Spanish guns from the era.

WASHINGTON NATIONAL CATHEDRAL — The Gothic-style cathedral contains the grave of Adm. George Dewey, commander of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron and later Admiral of the Navy. He’s buried beneath the Bethlehem Chapel, which contains a memorial to him. The 1898 Peace Cross, erected in part to commemorate the end of the war, is in a circle on the grounds overlooking Washington. Wisconsin and Massachusets avenues NW. Cathedral open 10 to 4:30 Monday through Saturday, and 12:30 to 4:30 on Sundays. 202/537-6200.

U.S. NAVAL ACADEMY — The U.S. Naval Academy Museum has an extensive special exhibit devoted to the Spanish-American War. It is expected to be there at least through September. The foremast of the USS Maine is located along the Academy seawall a short walk from the Armel-Leftwich Visitors Center. There are many other “significant historic items” related to the war located around the Naval Academy Yard, according to museum curator James Cheevers, who has compiled a list for tourists. The list is available at the information window on the main floor of the museum. Preble Hall, 118 Maryland Ave., Annapolis, on the Academy grounds. 410/293-2108. Museum open 9 to 5 Monday through Saturday, 11 to 5 Sundays.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HEALTH & MEDICINE — This museum on the grounds of Walter Reed Army Medical Center has scheduled an exhibit Sept. 11-Nov. 29 on medical aspects of the Spanish-American War, especially in Cuba and Puerto Rico. 6825 16th St. NW (enter through Georgia Avenue on weekends). 202/782-2200. Open daily 10 to 5:30. Free. Web site: http://www.natmedmuse.afip.org/

USS OLYMPIA — Dewey’s flagship is berthed at the Independence Seaport Museum, Penns Landing, Philadelphia. 215/925-5439. 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Combined admission to the Olympia and World War II submarine Becuna is $7.50 for adults, $3.50 children 5-12 (younger free) and $6 seniors. Museum-only and ships-only tickets are $5 for adults, $2.50 children and $4 seniors. Web site: http://www.libertynet.org/seaport/

The War Years

The “splendid little” Spanish-American War had both antecedents and postscripts that in retrospect make it seem somewhat less than splendid. What follows are some benchmarks along the way:

April 10, 1895 — Jose Marti, Cuban revolutionary, launches insurrection against Spanish rule.

Aug. 26, 1896 — Philippine revolution against Spanish rule begins. On Dec. 30, Filipino doctor Jose P. Rizal is executed for anti-Spanish writings.

Jan. 1, 1898 — In an effort to defuse the insurrection, Spain gives Cubans limited political autonomy.

Jan. 12 — Spaniards in Cuba riot against autonomy given to Cubans.

Jan. 25 — USS Maine arrives in Havana Harbor to protect American interests.

Feb. 15 — USS Maine explodes, sinks; 266 crewmen lost. The Maine’s captain urges suspension of judgment on the cause of the explosion.

March 28 — Naval Court of Inquiry says Maine destroyed by a mine.

April 11 — President William McKinley asks Congress for declaration of war.

April 25 — State of war exists between United States and Spain.

May 1 — Admiral George Dewey’s Asiatic Squadron, dispatched from the waters off Hong Kong by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, crushes Spanish fleet at Manila Bay.

June 10 — U.S. Marines land at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

June 12 — Revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo declares Philippine independence from Spain.

July 1 — Battles of El Caney and San Juan Hill in Cuba result in American victories and instant national acclaim for Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt, the former Navy Department official and future president who leads the Rough Riders at San Juan Heights.

July 3 — Spain’s Atlantic fleet, having sought refuge in the harbor of Santiago, Cuba, attempts to escape and is destroyed by American naval forces.

July 6 — Congress, caught up in expansionist fever fed by the war, votes to annex Hawaii, which has nothing to do with Spain. Within a few years, Filipinos immigrate to the islands in large numbers to work on the sugar plantations.

July 14 — Santiago surrenders. Yellow fever breaks out among American troops the next day.

July 25 — U.S. Army invades Puerto Rico.

July 26 — Spain asks for peace.

Aug. 6 — Spain accepts American terms for peace.

Aug. 12 — Truce is signed with Spain.

Aug. 13 — U.S. troops occupy Manila, prevent forces led by Philippine leader Aguinaldo from entering city.

Oct. 1 — Peace negotiations with Spain commence in Paris.

Dec. 10 — Spanish-American War ends, officially, with signing of the Treaty of Paris. United States pays Spain $20 million for Philippines. Spain also cedes Puerto Rico and Guam and agrees to renounce sovereignty over Cuba. In 1902, the United States declares Cuba independent, keeps naval base and the right to intervene in internal and foreign affairs.

Feb. 4, 1899 — Philippine Insurrection, also known as the Philippine-American War, begins. It is a war of guerrilla fighting, pacification and attrition.

March 23, 1901 — General Aguinaldo captured in the Philippines.

July 4, 1902 — President Theodore Roosevelt declares the Philippines pacified.

Celebrating Filipino Freedom

One hundred years ago today, Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo declared his country’s independence from Spain, which had ruled the Pacific archipelago since the 1500s. This declaration of independence, however, was summarily ignored by the United States, which had six weeks earlier destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay and within months would acquire the islands from Spain for $20 million.

There followed three years of bloody and bitter conflict known in American textbooks as the Philippine Insurrection and among Filipinos as the Philippine-American War.

No matter. The less messy part of our mutual history, under which the Philippines graduated from colony to commonwealth and, at long last, to independent country in 1946, is being celebrated here as the “USA-Philippine Festival: A Century of Freedom, Friendship and Partnership.”

There are events scheduled throughout the year and around the country. In Washington, the celebration will culminate in a focus on Filipinos and Filipino Americans at the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife on the Mall. But before then, there’s lots more. For information, call the number listed or Mitzi Pickard at 202/265-8163. Additional information is also at the Web site: http://us.sequel.net/centennial. Events are free, unless otherwise noted:

FRIDAY — 4 a.m.: Flag Raising Ceremony at Philippine Embassy, 1600 Massachusetts Ave. NW, to coincide with the flag raising ceremonies in the Philippines. Noon: lecture on the Philippine Collection at the National Museum of Natural History’s Baird Auditorium, 10th and Constitution NW. 5:30 p.m.: Exhibit of photographs of events leading to June 12, 1898, in the Philippines, at Philippine Embassy, Romulo Hall (also weekdays 1-2 p.m., through June 30). Contact Gloria Federigan, 703/893-8515. 6:30 p.m.: Philippine Centennial Fiesta Gala, JW Marriott Hotel, 1331 Pennsylvania Ave. NW. Tickets $80; call 301/340-1468 or 202/835-0875.

SATURDAY — 12:30-9 p.m.: Filipino American Youth Dialogue: “Planting Rice, Tracing Our Roots,” Funger Hall, George Washington University, 2201 G St. NW. Workshops and seminars of issues facing Filipino American youth. Contact Jojo Maralit, 301/423-8807.

SUNDAY — Filipino American Street Fair, 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. on Pennsylvania Avenue NW between Ninth and 11 streets. 3 p.m.: Parade from Seventh to 11th streets.

THURSDAY-JULY 2 — Philippine Centennial Film Celebration, a retrospective of nine Philippine films from 1961 to 1982. Freer Gallery of Art, Meyer Auditorium, 12th Street and Jefferson Drive SW, 202/357-2700.

JUNE 19 — 7 p.m. “Filipina Firsts: Salute to Filipino Women,” sponsored by the Philippine American Foundation, J.W. Marriott Hotel. Tickets $60; 202/467-5799.

JUNE 21 — 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.: Sports Fest/Family Picnic, Tucker Road Community Center, 1771 Tucker Rd., Fort Washington. 301/292-4203. Sponsored by Philippine American Foundation for Charities and the Philippine Festival Committee.

JUNE 24-28, JULY 1-5 — 100 community-based Filipino Master Artists will be at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the Mall. June 27 is Filipino American Day, with performances by Filipino Americans. 202/357-2700.

JUNE 26 — Lecture: “Conserving the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas: New Views From the Philippines.” At noon in the National Museum of Natural History’s Baird Auditorium.

JUNE 28 — Rizal Day and Youth Awards. Honoring outstanding Filipino American youths of the Washington area. From 2 to 4 at the Philippine Embassy, 1600 Massachusetts Ave. NW. 301/942-8713.

THROUGH JULY 8 — An exhibit highlighting the history of Filipino Americans in Hawaii (whose governor, Benjamin J. Cayetano, is of Philippine extraction) is on display in the State Department’s C Street lobby. The exhibit, on loan from the Bishop Museum in Hawaii, is sponsored by the Asian Pacific Federal Foreign Affairs Council. For information and access to the exhibit, which is directly behind the lobby security desk, call Cora Foley, 202/647-9264. 2300 C St. NW (Metro: Foggy Bottom).

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard