United States Department of Defense

News Release

No. 079-04

IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 5, 2004

Death of Retired U.S. Navy Admiral Thomas M. Moorer

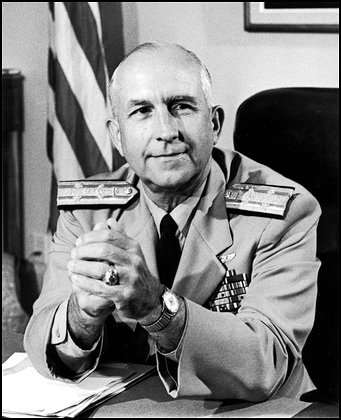

Retired U.S. Navy Admiral. Thomas Moorer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from July 1970 to June 1974 and chief of naval operations from 1967 to 1970, died today at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. He was 91.

The 41-year Navy veteran retired from active duty in 1974, ending a distinguished career that included service as the seventh chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and 18th Chief of Naval Operations.

Secretary of the Navy, the Honorable Gordon England, praised the admiral’s distinguished service by saying, “Admiral Thomas Moorer served his country with honor, courage and commitment throughout his active and dynamic life. His bravery in combat, his dedication and strong leadership as chief of naval operations and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff guided our Navy, and our armed forces, through some of the most turbulent years in America’s history.

Marine Corps General Peter Pace, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said, “I was deeply saddened to hear of the passing of Admiral Tom Moorer. He served the United States Navy and our great nation with distinction. Admiral Moorer’s legacy, as both Chief of Naval Operations, and as the seventh chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has made a lasting impression on all of us who have followed. On behalf of General Myers, and all the Joint Chiefs of Staff, I offer our heartfelt condolences. Our thoughts and prayers are with the Moorer family during this difficult time. May you draw comfort from your memories, as we remember fondly how Admiral Moorer served his country–and all of us–so well.”

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Vern Clark added, “Admiral Moorer’s leadership had a profound impact on our institution and a personal influence on many of us who were fortunate enough to serve under him. He displayed extraordinary courage both in combat and in the process of instituting positive change throughout our military.”

Born February. 9, 1912, in Mountt Willing, Alabama, Admiral Moorer graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933. After completing naval aviation training at the Pensacola Naval Air Station in 1936, he flew with fighter squadrons based on the carriers Langley, Lexington and Enterprise.

Admiral Moorer was serving with Patrol Squadron Twenty-Two at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, when the Japanese attacked in December 1941. His squadron subsequently participated in the Dutch East Indies Campaign in the Southwest Pacific where he flew numerous combat missions. Moorer received a Purple Heart after being shot down and wounded off the coast of Australia in February 1942 and then surviving an attack on the rescue ship, which was sunk by enemy action the same day.

Moorer received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his valor three months later when he braved Japanese air superiority to fly supplies into and evacuate wounded out of the island of Timor.

Tours afloat included operations officer aboard USS Midway and on the staff of Commander Carrier Division Four, Atlantic Fleet. Moorer commanded USS Salisbury Sound.

Promoted to Vice Admiral in 1962, Moorer took command of the Seventh Fleet, and in June 1964 became Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet as a full Admiral. One year later, he took command of NATO’s U.S. Atlantic Command and the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, becoming the first naval officer to command both the Pacific and Atlantic Fleets. President Johnson appointed him Chief of Naval Operations in 1967, and after serving almost three years, President Nixon selected him to be Chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff–the first naval officer to hold this position in 13 years.

On July 2, 1974, Admiral Moorer retired from active duty. At his retirement ceremony, a second Department of Defense Distinguished Service Medal was presented by Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger for extraordinary performance of duty and exceptional achievement as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from January 1973 to June 1974. In this citation, the secretary of defense said, “I particularly note that Tom Moorer has always put his country’s interests before anything else, and it is this quality I recognize in presenting him the only oak leaf cluster ever given to the Defense Distinguished Service Medal.”

Admiral Moorer is survived by his wife, the former Carrie Ellen Foy, and their four children.

Adm. Thomas Moorer Dies; Chaired Joint Chiefs of Staff

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Saturday, February 7, 2004

Navy Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, 91, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during crucial years of the Vietnam War who advocated aggressive force to win the conflict, died February 5, 2004, at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda after a stroke.

A tall, soft-spoken and stern southerner, Admiral Moorer was considered a master strategist often called on to handle tense and fragile situations. He occupied a series of increasingly prominent positions from the beginning of major military involvement in Vietnam until its end.

He was commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet during the disputed Tonkin Gulf clash between U.S. and North Vietnamese sea forces in 1964. The crisis led Congress to authorize President Lyndon B. Johnson to take all measures to protect U.S. forces and “to prevent further aggression.” This gave Johnson free rein to bomb North Vietnam and commit U.S. ground forces to the conflict in South Vietnam.

Admiral Moorer supported these measures.

From 1967 to 1970, he was Chief of Naval Operations, the Navy’s top uniformed officer and its representative among the joint chiefs. As the war in Vietnam continued, he grew frustrated with the executive branch’s strategy of containment of Communist forces in the North instead of total victory. He and other military officials felt the enemy would crumble only with a convincing show of force. He spent years trying to persuade officials to mine Haiphong Harbor, a supply route for Hanoi, until it was done in 1972.

By then he was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, the nation’s top military officer. He kept a relatively low public profile during his two-term tenure, which ended with his retirement in 1974. Among the issues, conflicts and resolutions he faced were arms-limitation talks with the Soviets, the Arab-Israeli War of 1973 and the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam.

Decades later, Admiral Moorer again figured in the news because of the war. He had been a source for a much-disputed 1998 CNN report on Operation Tailwind, which charged that U.S. forces used a lethal nerve gas on American defectors in Laos during the war.

CNN producers said Admiral Moorer confirmed the sarin gas story, but the admiral later denied independent knowledge of its use. CNN retracted the report, fired two producers and reprimanded the on-air reporter, Peter Arnett.

“It was an insult to the young men that do this very dangerous work to try to set up accusations they were trying to kill Americans,” he told The Washington Post. “It made everyone mad as hell. No Americans were killed, no gas was dropped.”

Thomas Hinman Moorer was a native of Mount Willing, Albama. His father was a dentist and state representative, and his mother was a teacher. The younger Moorer’s interests were mechanical engineering and military science, and at age 15 he was his high school class’s valedictorian.

Because of his age, he had to wait two years before admittance to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, where he was a varsity football lineman. He graduated in 1933 near the top of his class, whose members were the only ones to earn a commission in the Depression era Navy.

He completed flight training in Pensacola in 1936 and was stationed at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese launched a surprise attack on December 7, 1941. He was one of the first pilots to get his plane in the air.

He went with his squadron to the South Pacific as part of the effort to stem the Japanese advance toward Australia. On a reconnaissance mission, he and his crew were shot down by nine Japanese fighters, and the future admiral was wounded in the hip by shrapnel. The plane was in flames and speeding toward the water at 100 mph, but he managed to land the craft after bouncing three times on the water’s surface.

Rescued by a Philippine freighter, the crew was again besieged within minutes when Japanese dive bombers attacked the ship. He led those onboard to two lifeboats and guided them to an uninhabited island. He drew a large SOS sign in the sand and was spotted two days later by Australian fliers. For his actions, he received the Silver Star and the Purple Heart.

After the war, he attended the Naval War College in Rhode Island and held a succession of sea command posts and prestigious desk assignments. He was aided by Adm. Arleigh A. Burke, the brilliant and ambitious war hero whom Adm. Moorer served as assistant Chief of Naval Operations in the late 1950s.

He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1958, reportedly becoming at age 45 the youngest officer at the time selected for that rank. He made Vice Admiral in 1962 and full Admiral two years later. Time magazine called him “America’s fastest-rising sailor.”

In August 1967, Admiral Moorer became the 18th Chief of Naval Operations. The next January, the lightly armed spy ship Pueblo was seized by the North Koreans in what they claimed were its territorial waters. The commander, Lloyd M. Bucher, and his crew were held and tortured for 11 months before their release after signing false confessions.

A Naval Court of Inquiry had recommended Bucher be tried by court-martial, and Admiral Moorer supported it. Doing otherwise, he said, would set the principle not to fight back unless one could overwhelm the enemy. Bucher, who died last month, said his actions saved lives. In 1969, the Navy secretary declared Bucher had “suffered enough” and decided against a court-martial.

Admiral Moorer also faced concerns about proper war strategy in Vietnam and a period of Soviet military proliferation. In those matters, he advocated a determined approach: putting more troops in Vietnam on the advice of front-line commanders and supporting new technologies that made for quieter nuclear submarines.

According to a history of the chiefs of naval operations, Admiral Moorer felt many of his efforts to modernize the Navy’s fleet went unmet because Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara gave budgeting priority to services whose materiel and weaponry had deteriorated most in combat use. Naval warships did not meet that threshold.

Admiral Moorer was reappointed Chief of Naval Operations by President Richard M. Nixon in 1969 and named chairman of the Joint Chiefs the next year. He told an interviewer that the executive branch relied mainly on civilian advisers more than its military ones, leading to limitations in his power that not many in the public grasped.

He said there were those who felt the military was too weak to exert proper control of the war and those who felt it had too much influence over civilian authority. “Both of these allegations,” he said on his retirement, “are nonsense in its purest form.”

As a civilian, Admiral Moorer, a Bethesda resident, maintained an active interest in military and security affairs and testified on Capitol Hill about security concerns. He also accepted board memberships at Texaco and defense contractor CACI International, among other firms.

Survivors include his wife of 68 years, Carrie Foy Moorer of Bethesda; four children, Thomas R. Moorer of Dallas, Ellen Butcher of Fort Myers, Florida, Richard F. Moorer of Cabin John and Robert H. Moorer of Gaithersburg; two brothers; 10 grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, Who Headed Joint Chiefs in 70’s, Dies at 91

February 6, 2004

Admiral Thomas Hinman Moorer, a World War II hero who was appointed chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff by President Richard M. Nixon, died on Thursday, 5 February 2004, the Department of Defense said. He was 91.

A 41-year veteran of the Navy, Admiral Moorer was appointed as the military’s senior uniformed officer in 1970, and served in that post until he retired in 1974. Before that appointment he served as chief of naval operations for three years.

Admiral Moorer, a naval aviator who then had the rank of Lieutenant, was stationed at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked on December 7, 1941. Perhaps his most memorable military feat came a few months later, when his plane was shot down over the South Pacific.

He escaped from the plane, and led his crew to a freighter. Almost immediately, the ship came under attack and sank.

The aviator led his crew onto lifeboats and to the safety of an uninhabited island, where he made an enormous S.O.S. in the sand. He was awarded the Silver Star for his conduct.

“I struck the water at great force,” he recalled later of his plane’s downing, “but after bouncing three times, managed to complete the landing.”

Thomas Moorer was born on February 9, 1912, in Mount Willing, Alabama, the son of a dentist. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1933. He was valedictorian of his high school class, but had to wait two years, until he was 17, to enter the academy.

The young officer got his aviator wings at Pensacola, Florida, in 1936. His was one of the first American planes to get into the sky after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

He rose through the ranks of the Navy, holding several fleet commands at sea. Promoted to vice admiral in 1962, he took command of the Seventh Fleet and in June 1964 became commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet. In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson chose him to be chief of naval operations, the service’s top officer.

Admiral Moorer later became the first naval officer in 13 years to hold the position of chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

During the Vietnam War, Admiral Moorer was a strong advocate of using naval and air power to dissuade North Vietnam from its support of insurgency in South Vietnam and Laos, Edward J. Marolda, senior historian at the Naval Historical Center, has written.

After he retired, Admiral Moorer remained in the public eye, commenting frequently on current events and policy decisions by American administrations. He opposed the transfer of control of the Panama Canal, and wrote a paper warning about China’s expanding international importance.

In 1998, Cable News Network reported that he had confirmed the use of nerve gas in Laos, during the Vietnam War. After inquiries by both the Pentagon and CNN’s own legal team found insufficient evidence to support the accusations, CNN and Time magazine executives retracted the accounts and issued apologies. The network later negotiated an undisclosed settlement with Admiral Moorer.

NOTE: Admiral Moorer will be laid to rest in Arlington National Cemtery at 1500 hours on 20 February 2004.

Navy Admiral Moorer, 91, Dies

The Navy Admiral Was Joint Chiefs Chair During Vietnam

By Adam Bernstein

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Friday, February 6, 2004

Navy Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, 91, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during crucial years of the Vietnam War who advocated aggressive force to win the conflict, died yesterday at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda after a stroke.

A tall, soft-spoken and stern Southerner, Admiral Moorer was considered a master strategist often called on to handle tense and fragile situations. He occupied a series of increasingly prominent positions from the beginning of major military involvement in Vietnam until its end.

He was commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet during the disputed Tonkin Gulf clash between U.S. and North Vietnamese sea forces in 1964. The crisis led Congress to authorize President Lyndon B. Johnson to take all measures to protect U.S. forces and “to prevent further aggression.” This gave Johnson free rein to bomb North Vietnam and commit U.S. ground forces to the conflict in South Vietnam.

Admiral Moorer, who believed that success in war depended on the use of force, supported these measures.

From 1967 to 1970, he was chief of naval operations, the Navy’s top officer. As the war in Vietnam continued, he grew frustrated with the executive branch’s strategy of containment of Communist forces in the North instead of total victory. He and other military officials felt the enemy would crumble only with a convincing show of force. He spent years trying to persuade officials to mine Haiphong Harbor, a supply route for Hanoi, until it was done in 1972.

By then he was chairman of the Joint Chiefs, the nation’s top military officer. He kept a relatively low public profile during his two-term tenure, which ended with his retirement in 1974. Among the issues, conflicts and resolutions he faced were arms-limitation talks with the Soviets, the Arab-Israeli War of 1973 and the American withdrawal from Vietnam.

Decades later, Admiral Moorer again figured in the news because of the war. He had been a source for a much-disputed 1998 CNN report on Operation Tailwind, which charged that U.S. forces used a lethal nerve gas on American defectors in Laos during the war.

CNN producers said Admiral. Moorer confirmed the sarin gas story, but the admiral later denied independent knowledge of its use. CNN retracted the report, fired two producers and reprimanded the on-air reporter, Peter Arnett. CNN paid Adm. Moorer an undisclosed sum.

“It was an insult to the young men that do this very dangerous work to try to set up accusations they were trying to kill Americans,” he told The Washington Post. “It made everyone mad as hell. No Americans were killed, no gas was dropped.”

Thomas Hinman Moorer was a native of Mount Willing, Ala. His father was a dentist and state representative, and his mother was a teacher. The younger Moorer’s interests were mechanical engineering and military science, and at age 15 he was his high school class’s valedictorian.

Because of his age, he had to wait two years before admittance to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, where he was a varsity football lineman. He graduated in 1933 near the top of his class.

He completed flight training in Pensacola in 1936 and was stationed at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese launched a surprise attack on December 7, 1941.

He went with his squadron to the South Pacific as part of the effort to stem the Japanese advance toward Australia. On a reconnaissance mission, he and his crew were shot down by nine Japanese fighters, and the future admiral was wounded in the hip by shrapnel. The plane was in flames and speeding toward the water at 100 miles per hour, but he managed to land the craft after bouncing three times on the water’s surface.

Rescued by a Philippine freighter, the crew was again besieged within minutes when Japanese dive bombers attacked the ship. He led those onboard to two life boats and guided them to an uninhabited island. He drew a large SOS sign in the sand and was spotted two days later by Australian fliers. For his actions, he received the Silver Star and the Purple Heart.

Navy Admiral. Moorer, 91, Dies

After the war, he attended the Naval War College in Rhode Island and held a succession of sea command posts and prestigious desk assignments. He was aided by Adm. Arleigh A. Burke, the brilliant and ambitious war hero whom Adm. Moorer served as assistant chief of naval operations in the late 1950s.

He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1958, reportedly becoming at age 45 the youngest officer at the time selected for that rank. He made Vice Admiral in 1962 and full Admiral two years after. Time magazine called Admiral. Moorer “America’s fastest-rising sailor.”

He developed an expertise in war-gaming and piquant analogies to deride the “numbers-racket people” — his term for Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and his aides.

“Arnold Palmer played golf the other day,” he began one story. “In terms of your weapons-analysis system he used his 5 iron three times, his driver 18 times and his putter 38 times. Well, according to your system, if he wants to play even better golf, he should go out and get more putters.”

In August 1967, Admiral Moorer became the 18th chief of naval operations. The next January, the lightly armed spy ship Pueblo was seized by the North Koreans in what they claimed were its territorial waters. The commander and crew were held and tortured for 11 months before their release.

Admiral Moorer pressed for the court-martial of Commander Lloyd M. Bucher. Bucher, who died last month, was pardoned by the Navy Secretary for having “suffered enough.”

Admiral Moorer also faced concerns about proper war strategy in Vietnam and a period of Soviet military proliferation. In those matters, Adm. Moorer advocated a determined approach: putting more troops in Vietnam on the advice of front-line commanders and supporting new technologies that made for quieter nuclear submarines.

According to a history of the chiefs of naval operations, Admiral Moorer felt many of his efforts to modernize the Navy’s fleet went unmet because McNamara gave budgeting priority to services whose materiel and weaponry had deteriorated most in combat use. Naval warships did not meet that threshold.

Admiral. Moorer was reappointed CNO by President Richard M. Nixon in 1969 and named chairman of the Joint Chiefs the next year. He told an interviewer that the executive branch relied mainly on civilian advisers more than its military ones, leading to limitations in his power that not many in the public grasped

He said there were those who felt the military was too weak to exert proper control of the war and those who felt it had too much influence over civilian authority. “Both of these allegations,” he said on his retirement, “are nonsense in its purest form.”

He added that, in reflection, World War II had largely defined his perspective. After being shot down, sunk and finally rescued in the South Pacific, he vowed to himself and his comrades that all crises thereafter would be anticlimactic.

Survivors include his wife of 68 years, Carrie Foy Moorer of Bethesda; four children, Thomas R. Moorer of Dallas, Ellen Butcher of Fort Myers, Florida, Richard F. Moorer of Cabin John and Robert H. Moorer of Gaithersburg; two brothers; 10 grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

As a civilian, Admiral Moorer, a Bethesda resident, maintained an active interest in military and security affairs and testified on Capitol Hill about security concerns. He also accepted board memberships at Texaco and defense contractor CACI International, among other companies.

Courtesy of the Eufaula (Alabama) Tribune

The death last Thursday of Retired Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, one of the heroes of The Greatest Generation, touched Eufaula in a personal and public way.

The distinguished Admiral’s brother, Dr. Billy Moorer, is one of Eufaula’s most respected citizens, and Admiral Moorer’s wife of 68 years, the former Carrie Ellen Foy, is a member of the prominent Foy family. Adm. Moorer’s parents also made their home in Eufaula, moving here in 1927 and remaining here for the rest of their lives.

Admiral Moorer Middle School is named for the naval hero, and he established a scholarship for essay winners there. Many Eufaulians still recall the two-day celebration that occurred in April 1971, when Adm. and Mrs. Moorer came for the dedication of the school. With them came a host of dignitaries from the military and civilian sectors. They took pride in the recognition of the then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The Moorer Room on the second floor of Shorter Mansion is another tribute to the admiral. It is filled with a collection of items and memorabilia he donated for display in his hometown.

Admiral Moorer died February 5, 2004, at Bethesda Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland, at the age of 91, after suffering a stroke about two weeks before.

The U.S. Navy plans a burial with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, but a time had not been set as of press time.

A decorated World War II hero, Admiral Moorer rose quickly to the top in the ranks of Navy officers, capping his career with service as Chief of Naval Operations and also Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. His retirement from active duty in 1974 closed a 41-year career in the Navy.

After his retirement, Admiral Moorer visited Eufaula about once a year. He, his brother Dr. Billy, and their younger brother, Retired Admiral Joe Park Moorer of Ponte Vedra, Florida, enjoyed fishing and hunting together.

Dr. Billy Moorer said, “Tom has always felt a strong connection to Eufaula. We moved here from Montgomery just after he had graduated from high school. He went to work for Slade Lumber Company here. He saw a movie (‘we called it a picture show’) about West Point and got interested in the military.

Dr. Moorer said his brother had to wait two years until he was 17 years old for an appointment to the Naval Academy. He graduated in 1933 with the rank of ensign. After a couple of years of fleet duty, he went to Pensacola, Florida, for training as a naval aviator.

“This was an especially fortunate move,” Dr. Moorer said, “because he was in love with a Eufaula girl, Carrie Foy. They were married in 1935 in the Foy house which was on Barbour Street just east of the Methodist church.”

Dr. Billy says Carrie Moorer’s love and dedication to her husband, his family and his career was a major source of support for him.

Dr. Moorer continued, “Our mother was a devout Baptist Sunday school teacher. Tom always said her close connection with the Lord helped him survive World War II.

“Soon after Tom got his wings, Mama advised him to fly ‘low and slow.’ Tom thanked her for thinking of his safety but to fly low and slow would be the most dangerous thing he could do.”

In a press release from the U.S. Department of Defense, Secretary of the Navy Gordon England praised Moorer’s distinguished service.

“Admiral Thomas Moorer served his country with honor, courage and commitment throughout his active and dynamic life,” England said. “His bravery in combat, his dedication and strong leadership as chief of Naval Operations and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff guided our Navy, our armed forces through some of the most turbulent years in America’s history.”

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Vern Clark praised Adm. Moorer’s impact on the Navy.

“Admiral Moorer’s leadership had a profound impact on our institution and a personal influence on many of us who were fortunate enough to serve under him. He displayed extraordinary courage both in combat and in the process of instituting positive change throughout our military.”

Born February 9, 1912, in Mt. Willing in Lowndes County, Admiral Moorer was the son of Dr. R. R. Moorer, a dentist, and Hulda Moorer, a schoolteacher. At age 15, he graduated valedictorian of his class from Cloverdale High School in Montgomery. While at the Naval Academy at Annapolis, he was a varsity football lineman. He graduated in 1933 near the top of his class, whose members were the only ones to earn a commission in the Depresssion-era Navy.

He completed flight training in Pensacola in 1936 and was stationed at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked December 7, 1941.

Pearl Harbor

On the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Dr. Billy Moorer shared his recollection of that December 7 morning. He told The Tribune he was concerned because Tom was stationed there and Carrie and their young son Tommy were also there. At the time of the pre-dawn attack, “Tom was flying a PBY patrol bomber on Ford Island, where the battleships were tied up. His plane was one of the very few that was not damaged. When he returned to Pearl Harbor, he took off again in search of Japanese carriers.

“He said when he took off the surface of the harbor was so filled with oil it was difficult to take off in his sea plane.

“For the next two months, he flew patrols every day looking for Japanese planes.”

One of Moorer’s most heroic feats came only months later, in February, 1942, while he was flying combat missions north of Australia. His plane was shot down, but he escaped and led his crew to a Philippine freighter. Almost immediately, the ship came under attack and sank. Moorer led his crew onto lifeboats and to the safety of an uninhabited island, where he made an enormous SOS in the sand. Dr. Billy said it was about four days before he was rescued. He was awarded the Silver Star and a Purple Heart for his heroism.

Three months later, he received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his valor when he braved Japanese air superiority to fly supplies into and evacuate wounded out of the island of Timor.

Promoted to Vice Admiral in 1962, Moorer took command of the Seventh Fleet, and in June 1964 became Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet as a full Admiral. Time magazine called him “America’s fastest-rising Sailor,” according to the Washington Post.

Atlantic/Pacific commands

One year later, he took command of NATO’s U.S. Atlantic Command and the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, becoming the first naval officer to command both the Pacific and Atlantic Fleets. President Johnson appointed him chief of naval operations in 1967, and after serving almost three years, President Nixon selected him to be chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a position he held until his retirement in 1974.

At his retirement ceremony, a second Department of Defense Distinguished Service Medal was presented by Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger for extraordinary performance of duty and exceptional achievement as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from January 1973 to June 1974 (His second term). Schlesinger said, “I particularly note that Tom Moorer has always put his country’s interests before anything else, and it is this quality I recognized in presenting him the only oak leaf cluster ever given to the Defense Distinguished Service Medal.”

After retirement, Admiral Moorer revealed his frustration during the Vietnam War with the executive branch’s strategy of containment of Communist forces in the North instead of total victory. He fought for years to get officials to mine Haiphong Harbor, a supply route for Hanoi, until it was done in 1972. He also told an interviewer that the executive branch relied mainly on civilian advisers more than its military ones, leading to limitations on his power that not many in the public grasped at the time.

For most of his retirement, he remained in the pubic eye, commenting candidly on current events and policy decisions by U.S. administrations. In fact, Dr. Billy Moorer said his most recent appearance on television was on January 9 of this year. Dr. Billy said that in retirement, “Tom didn’t fade away into easy retirement of golf and fishing. His sharp mind and broad experience kept him very busy. He often testified before Congress. For example, he strongly opposed President Carter’s action of giving away the Panama Canal.”

Several times during his visits to Eufaula, he graciously consented to interviews with The Tribune, sharing with readers his impressive grasp of current events and trouble spots around the globe. His commentary was always concise, and it was delivered in a lively manner. He drew on his extensive knowledge of the world scene to elaborate on his responses, offering up for local readers a chance to become better informed about national and international issues. He never left any doubt where he stood on any of them.

He successfully sued CNN after a 1998 Cable News Network report that he had confirmed the use of nerve gas in Laos during the Vietnam War. Inquiries by both the Pentagon and CNN’s legal team found insufficient evidence to support the accusation. CNN and Time magazine executives retracted the accounts and issued apologies. They settled for an undisclosed amount.

Survivors include, his wife, Carrie Ellen Foy Moorer, Bethesda, Maryland; four children, Thomas R. Moorer, Dallas, Texas; Ellen Butcher of Ft. Myers, Florida; Richard F. Moorer, Cabin John, Maryland and Robert H. Moorer, Gaithersburg, Maryland; two brothers, Dr. Billy Moorer, Eufaula, Retired Admiral Joe Park Moorer, Ponte Vedra, Florida.; 10 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

The Moorer brothers also had a sister, Alice, who died several years ago.

MOORER, THOMAS H

- ADM US NAVY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 07/31/1940 – 07/31/1974

- DATE OF BIRTH: 02/09/1912

- DATE OF DEATH: 02/05/2004

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 02/24/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 1 SITE 171-H

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

The caisson funeral procession of Retired U.S. Navy Admiral Thomas Moorer winds

through Arlington National Cemetery February 23, 2004. Moorer, who was

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from July 1970 to June 1974,

died February 5 at the age of 91.

The caisson carrying the casket of retired U.S. Navy Admiral Thomas Moorer and his

honor guard wind through Arlington National Cemetery February 24, 2004. Moorer,

who was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from July, 1970 to June, 1974,

died February 5 at the age of 91.

The flag-drapped coffin containing retired U.S. Navy Adm. Thomas Moorer is

transported on an artillery caisson to his grave during a full honors military funeral at

Arlington National Cemetery, February 24, 2004. Moorer was Chairman of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff from July 1970 to June 1974.

Carrie Moorer, widow of retired U.S. Navy Admiral Thomas Moorer, is presented the U.S. flag

from his casket by his brother, Joseph Moorer (R) during a full honor military funeral

at Arlington National Cemetery, February 24, 2004. Moorer was Chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff from July 1970 to June 1974.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard