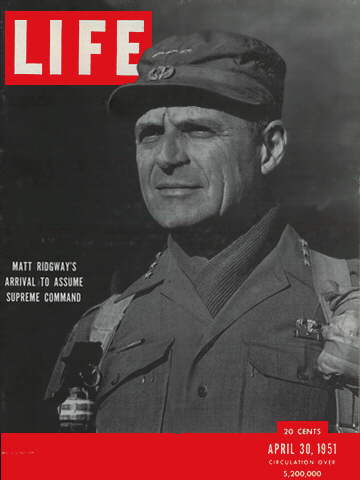

From a contemporary press report: March 1993:

The general who became Chief of Staff after leading U.S. forces in Normandy and United Nations troops in Korea, died at home in Fox Chapel, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh. Was 98. Died of cardiac arrest, said his lawyer, G. Donald Gerlach.

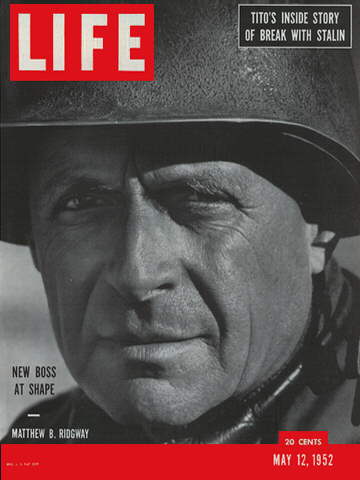

He also planned and executed the Army’s first major Airborne assault, in Sicily in WWII, and was a soldier-diplomat who served on several international commissions. In April 1951 he succeeded General of the Army Douglas MacArthur as commander of United Nations forces in Korea and of allied occupying forces in Japan. In June 1952 he replaced General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower as Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe. In 1953 he was appointed Army Chief of Staff by President Eisenhower, under whom he had served in WWII. But what should have been the capstone of distinguished military career ended in bitter frustration for him in 1955, when he retired after finding himself in almost constant disagreement with Eisenhower, the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. At one point, the President bluntly told him that his views were “Parochial” because he did not accept new strategy of using the threat of atomic bombs delivered by airplanes as nation’s chief line of defense and de-emphasizing the role of the foot soldier. He objected to the strategy as failing to adequately develop concepts of using airpower, nuclear weapons and ground soldiers in conjunction in distant conflicts. But he continued to fight budget cuts for the Army.

“Throughout my 2 years as Chief of Staff,” he recalled later, “I felt I was being called upon to tear down, rather than build up, ultimately decisive element in a properly proportioned fighting force on which the world could rest its hope for maintaining the peace or, if the catastrophe of war came, for enforcing its will upon those who broke that peace.”

Although he was otherwise known as an unflamboyant officer, he had one habit that became his trademark. Just as General George S. Patton was famous for wearing twin pearl-handled revolvers in WWII, he always had a hand grenade attached to one shoulder strap on his battle jacket, and a first aid kit on the other. “Some people thought I wore the grenades as a gesture of showmanship,” he said years later. “This was not correct. They were purely utilitarian. Many a time in Europe and Korea, men in tight spots blasted their way out with hand grenades.”

Matthew Bunker Ridgway was proud of the fact that he an “Army Brat,” son of Colonel Thomas Ridgway, an artillery officer, and the former Ruth Starbuck Bunker. He was born March 3, 1895, Ft Monroe, Virginia, where his father was stationed. He said in his memoirs “Soldier,” (Harper & Brothers, 1956) that his “earliest memories are of guns and Marching men, of rising to the sound of the reveille gun and lying down to sleep at night while the sweet, sad notes of ‘Taps’ brought the day officially to an end.” He was reared on several Army posts and grad from English High School in Boston in 1912.

His first attempt to enter West Point was unsuccessful because he failed geometry on his entrance examination. But he succeeded on second try and in 1913 he entered the academy, where be became undergraduate manager of the football team. He graduated in 1917, was commissioned a Second Lieutenant of Infantry and, in anticipation of being sent to fight in WWI, was quickly promoted to First Lieutenant and then to temporary Captain. But he did not go overseas; instead, he went to Eagle Pass, Texas, where he commanded an Infantry company.

In 1918 he returned to West Point, became an instructor in Spanish and later manager of the athletics program. In 1925 he completed the Company officers course at the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and was given his first overseas assignment, command of a company in the 15th Infantry in Tsientsin, China.

Routine Infantry duty in U.S. followed. But in 1927, because of his fluency in Spanish, he was asked by Major General Frank Ross McCoy to become member of a U.S. mission to Nicaragua, charged with supervising free elections in that war-torn republic. He had hoped to be part of the Army’s pentathlon team in 1928 summer Olympic Games in Amsterdam, but he recalled later that he had realized that “I could not reject so bright an opportunity to prepare myself for any military-diplomatic role that the future might offer.” It was the first of several diplomatic assignments.

He sat on a commission that adjudicated differences between Bolivia and Paraguay, and in 1930 became a military adviser to Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., then Governor General of Philippines. His success in that assignment led to his appointed to the Army’s Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. After completing that 2-year course in 1937, he became one of the elite Army officers marked for quick advancement and top leadership. By then had been promoted to Major and had come under the wing of George C. Marshall, then a Brigadier General, who, as Army Chief of Staff designate, took him to Brazil on a special assignment.

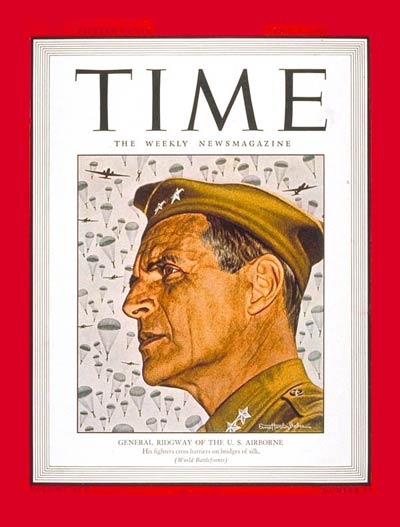

In September 1939, when WWII erupted in Europe, was sent to the war plans Division of War Department’s General staff in Washington, DC. It was much-desired assignment because it was from war plans Division that senior officers were selected for higher command. By August 1942 he was a Brigadier General and in command of newly activated 82nd Infantry Division. When it became one of the Army’s first 2 Airborne divisions he remained in command and won his Paratrooper wings. In North Africa in the spring of 1943, he planned the Army’s first major night Airborne operation, part of the invasion of Sicily. The invasion, which began on July 10, 1943, led to a rapid conquest of the western half of the island. By the end of the month all resistance had ceased. That first Airborne attack, involving Paratroopers dropped from airplanes and troops flown into enemy territory on gliders, made American military history, but it was carried out with severe losses. Both enemy and Allied antiaircraft gunners shot down more than a dozen of the 82nd’s transport planes. These and other losses resulted from staff failure, mistaken instructions and the newness of such an operation. As a result, he, along with other Airborne commanders like Maxwell D. Taylor and James M. Gavin, had a difficult time persuading higher command of the ultimate effectiveness of landing soldiers and equipment by parachute and gliders.

Although he had not jumped into battle with his troops in the Sicilian campaign, he insisted on a combat jump into Normandy before D-Day, June 6, 1944. The citation to the OLC on his DSC said that in the Normandy jump he “exposed himself continuously to fire” and “personally directed the operations in important task of securing the bridgehead over the Merderet River.” His recollection of his jump was slightly less reverential. “I was lucky,” he said. “There was no wind and I came down straight, into a nice, soft, grassy field. I recognized in the dim moonlight the bulky outline of a cow. I could have kissed her. The presence of a cow meant the field was not mined.”

A few months after D-Day, he was given command of the new 18th Airborne Corps and directed its operation in the vicinity of Eindhoven, the Netherlands, in the Ardennes and along the Rhine River. His troops battled the German “Ruhr Pocket” and finally, on May 2, made a historic link up with Soviet troops on the Baltic. “General Ridgway has firmly established himself in history as a great battle leader,” General Marshall said later. “The advance of his Army corps to the Baltic in the last phase of the war in Europe was sensational to those fully informed of the rapidly moving events of that day.”

The war over, he, early in 1946, went to London as Eisenhower’s military adviser to the U.S. Delegation to the United Nations Assembly. He helped draft a plan for an international United Nations force to curb aggression, a force that he himself was destined to command a few years later in Korea. In the late 1940’s, he was commander of U.S. forces in Caribbean, a post more diplomatic that military.

By late Dec 1950 was a Lieutenant General, serving as Army Deputy Chief of Staff in the Pentagon, when word came that Lieutenant General Walton H. Walker, commander of the 8th Army in Korea had been killed in a jeep crash. The 8th Army was then in full retreat from Chinese Communist forces, which had opened a massive counteroffensive a month before, and was fleeing back across 38th Parallel, which divided South and North Korea. He was named Walker’s successor and was soon on his way to Korea. Was credited with rallying United Nations forces, whose morale had been severely strained by heavy losses and bitterly cold weather. He stayed conspicuously at the front lines, exhorting his troops to concentrate on killing the enemy rather than trying to regain ground. But in a series of hard-fought counteroffensives, he succeeded in driving the Communist forces out of all but the northwestern corner of South Korea, seizing strategic territory north of the 38th Parallel.

Then in 1951 came the epic clash between his superior, General Douglas MacArthur, who was overall allied commander in the Far East, and President Harry S. Truman. General MacArthur, embittered by the Chinese Communist forces’ victory south of the Yalyu River in North Korea, proposed various steps to defeat the enemy, including “unleashing” the Chinese Nationalists on Taiwan against mainland China. President Truman, afraid that such measures might widen the war, ruled out General MacArthur’s ideas. Then the General made the disagreement public. Ridgway wrote later, in his 1967 book, “The Korean War,” that the confrontation was a “clash of wills, bordering closely on insubordination.” On April 11, 1951, Truman removed Genera MacArthur, a national hero, from his command in the Far East, provoking a public uproar, and named Ridgway to succeed him. James A. Van Fleet replaced Ridgway as commander of United Nations forces in Korea, where the war settled into a stalemate while peace talks dragged on for two years at Pananmujon, near the 38th Parallel. Fighting ended on July 27, 1953, when Chinese and North Koreans signed an armistice with United Nations and South Korean forces.

In Tokyo, he generally followed occupation policies established by MacArthur. The occupation essentially ended with the signing of a peace treaty in San Francisco on September 8, 1951. The next year he succeeded Eisenhower as Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe. In 1953, he received what he was to call “the toughest, most frustrating job of my whole career,” his appointment as Army Chief of Staff.

Seeing what he regarded as dangerous efforts to downgrade the role of the Army, clashed repeatedly with Charles E. Wilson, Secretary of Defense, and Admiral Arthur Radford, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Finally, a few months short of his original retirement date, he left the Army in June 1955.

In retirement in Pittsburgh, the old soldier grew increasingly dissatisfied with nation’s military policy. He summed up his resentments in 1979, after Pentagon ordered paratroopers to stop wearing the Airborne’s distinctive red beret, symbol of paratrooper spirit. After urging that order be reversed, General Ridgway asserted: “I publicly protested the adoption of the volunteer Army, now a demonstrated failure and perhaps a disaster. I publicly deplored the dismantling of Selective Service and the admission of women into our service academies. Every one of those actions is now looming as potentially detrimental to the esprit and effectiveness of our armed forces – a blow at discipline, without which no military unit is worth its keep.”

In 1986, he was awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom. The citation said: “Heroes come when they are needed. Great men step forward when courage seems in short supply. WWII was such a time, and there was Ridgway.”

In 1991, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by General Colin Powell, the current Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

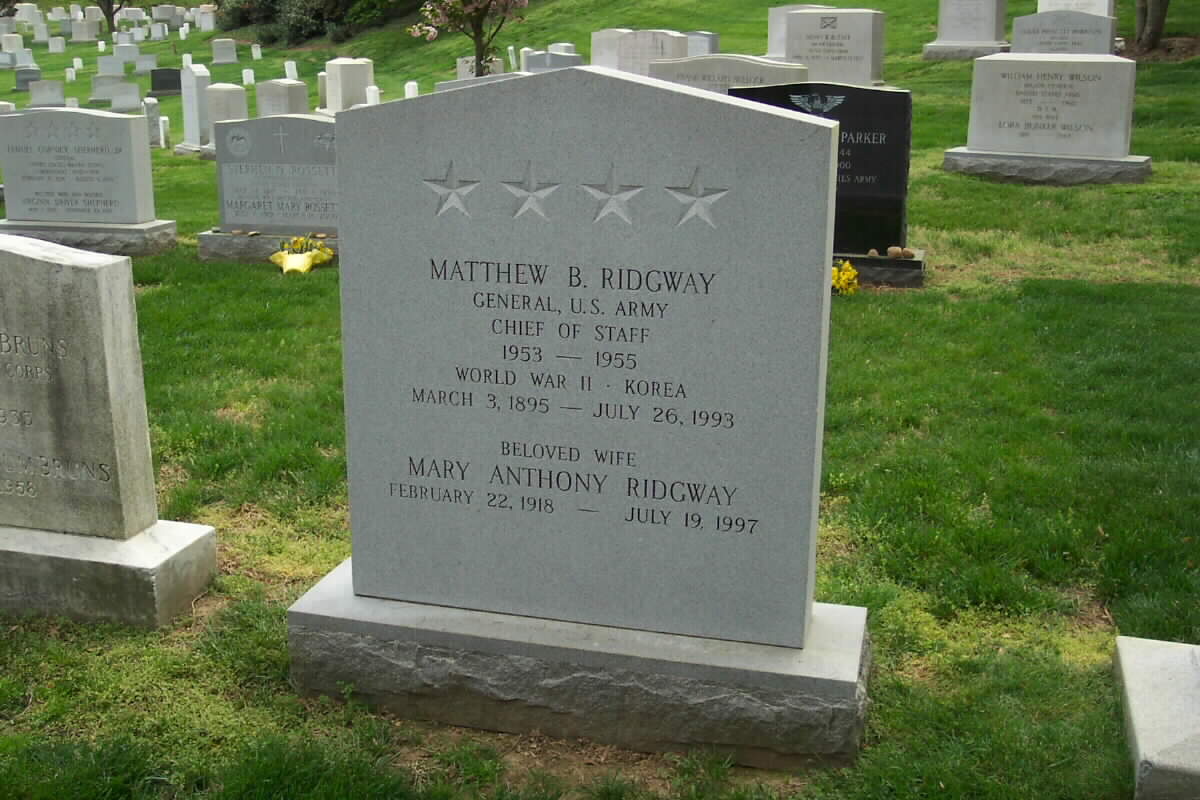

His first marriage, to former Caroline Blount, ended in divorce. A second marriage, to Margaret Wilson, also ended in divorce. In 1947 married Marjory Anthony Long. In addition to his wife, Marjory, who is known as Penny, he is survived by 2 daughters, Constance and Shirley. A graveside service is to be held at Arlington National Cemetery at 1:30 PM Friday, July 30, 1993. He had 2 daughters by his first marriage, Constance and Shirley, with whom he had lost touch. A son from third marriage, Matthew B. Ridgway, Jr., died in train accident in 1971. (NOTE: Matty was graduated from Bucknell in June, 1971, and received his commission as a Second Lieutenant in the Army Reserve the same month. Then he left for a canoe camp at Lake Timagami in Ontario, where he was to act as a guide nd counselor for teen-age boys on an eight-week canoe trip. During an early portage they were walking along a railroad track, Matt in the lead, a canoe over his head in Indian fashion, when a train came speeding down the track. The boys scrambled up an embankment to safety, but the train struck an end of Matty’s canoe, knocked it around, and broke his neck. The stunned parents flew to Canada. After a time they boarded a private plane that took them over the Lake of the Woods. With them they had Chaplain Gordon Mercer of the Canadian Armed Forces. As they neared the northern end of the lake the flare chute was opened, and, kneeling on the lurching floor of the plane, they shared a two-minute prayer. Then they committed the ashes of their son to the beautiful Canadian lake and forest country he had loved so dearly.

RIDGWAY, MATTHEW BUNKER

(First Award)

Synopsis:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Matthew Bunker Ridgway (0-5264), Major General, U.S. Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Commanding General, 82d Airborne Division, in action against enemy forces in July 1943.

Major General Ridgway’s intrepid actions, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 82d Airborne Division, and the United States Army.

Headquarters, Seventh U.S. Army, General Orders No. 24 (September 11, 1943)

RIDGWAY, MATTHEW BUNKER

(Second Award)

Citation:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Second Award of the Distinguished Service Cross to Matthew Bunker Ridgway (0-5264), Major General, U.S. Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Commanding Officer, 82d Airborne Division, in action against the enemy from 6 June 1944 to 9 June 1944, in France.

Major General Ridgway jumped by parachute at approximately 0200 prior to the dawn of “D” Day and landed about 3/4 mile northeast of *****, France, to spearhead the parachute landing assault of his Airborne Division on the ****.

Throughout “D” Day, he visited every point in the then surrounded area in order to evaluate the opposition and to encourage his men. He penetrated to the front of every active sector without thought of the personal danger involved. He exposed himself continuously to small arms, mortar and artillery fire; as, by his presence and through words of encouragement, he greatly assisted and personally directed the operations of one of his battalions in the important task of securing the bridgehead across the ***** River, which required a frontal assault against strongly entrenched enemy positions. His personal bravery and his heroism were deciding factors in the success of his unit in France.

Major General Ridgway’s gallant leadership, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 82d Airborne Division, and the United States Army.

Headquarters, First U.S. Army, General Orders No. 35 (July 19, 1944)

Murray Kempton: Newsday, Wednesday, July 28, 1993:

“The Old Army is finally dead and departed with all the honor it generally managed to live by. The funeral of General Matthew B. Ridgway has to be its last rite. He was 98 and had buried every comrade who had served with him between the two World Wars and had been his command-fellows in the second of them.

Ridgway was the end of the line for the Old Army; and it is peculiarly fitting for him to have been behind all his brothers in arriving at the grave, because he was the best of them. His historic advance from commands of the 82nd Airborne in Normandy, the 8th Army in Korea and NATO, and reached its summit as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army.

There is always a mystery about successes achieved with entire disdain for the perils of the impolitic speech. In “Soldier,” his autobiography, Ridgway recalls a 1950 meeting where the Joint Chiefs of Staff wondered what they could do to restrain General Douglas MacArthur from his head-over-heels plunge toward the Chinese border and disaster in Korea. The chiefs could already look at the map and recognize that MacArthur had arrayed his troops as for a parade, divided their columns and left between them the mountain where enemies could assemble in peace and await the securest chance for war. The chiefs had passed the hours helplessly struggling between their awe of a commander who had been riding with the Cavalry when they were in rompers and their awareness of his terminal folly. Ridgway was then only deputy Chief of Staff and forbidden to speak up in the company of his superiors. Crisis compelled him to break the laws of silence at last. “We owe it to ourselves,” he said, to call MacArthur to halt; and it must be done now because even tomorrow could be too late. The chiefs sustained the shock of this breach of Old Army custom and continued to sit inert until what they knew might happen did and all too soon.

After the meeting, Air Force Chief of Staff Hoyt Vandenberg congratulated him for his courage. His answer was not thanks for the compliment but renewed urgings that MacArthur be curbed. “Oh, what’s the use,” Vandenberg replied. “He won’t listen.” And, thereafter of course, it would be for Ridgway to restore the ruin of the Korean campaign.

He was dispatched to Tokyo and command of an 8th Army that MacArthur was by then glad to have someone else do with as he pleased. MacArthur had once called Korea “Marches’ last gift to an old warrior” and Marches had presented him with extinguishment of his old boundlessly assured self. He had, he told Ridgway, discovered that air power alone cannot stop determined troops. This was hardly news to Ridgway, who had jumped out of planes into hard punishments in Europe; and it was for him to savor the irony and pity of this great old soldier who had first learned war while depending on horses and then finally found defeat from overmuch trusting machines. Ridgway left for Korea and the restoring of his beloved foot soldiers to order enough to recapture the original lines from which MacArthur had too rashly leapt. He had saved the state of things and his common sense contented him with this half of a victory that would turn out to be his last of any sort.

His tenure as Army Chief of Staff was a series of quarrels with what he took to be President Dwight Eisenhower’s refusal to remember that most of what counts in battle is the Infantry. In 1955 he decided to retire. By then he and MacArthur may have been both outdated, the elder for being too much the politician and the younger for being no politician at all. Then came the death of the son born to Matthew Ridgway’s middle age and cherished above all else in his life; and there was a bitter cast to most of what was heard from him since.

Old age must have been for him the shipwreck it was for MacArthur. The Old Army had it faults, but it held the line and its grandeur has left no wreath with a sweeter smell than this, the last one of all.”

PENTAGRAM:

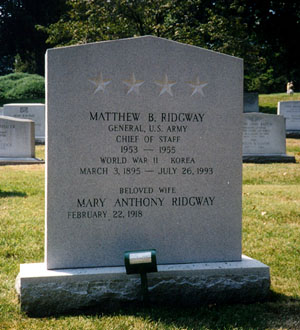

The Army buried an era at Arlington National Cemetery Friday when the remains of General Matthew B. Ridgway were laid to rest following a graveside ceremony, it was the burial of the last of the Generals who became famous while leading American soldiers across North Africa, Sicily, Italy and Europe during WWII.

The Service was attended by Secretary of Defense Les Aspin, Chairman of JCS General Colin L. Powell, Army Chief of Staff General Gordon R. Sullivan, former Army Chief of Staff retired General Carl E. Vuono, acting Military District of Washington Commander Brigadier General Clara L. Adams-Ender and a number of other U.S. and foreign officers. Ridgway, who commanded 82nd Airborne Division, and later the XVIII Airborne Corps during the war, is often mentioned along with other European-Theater leaders Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, George S. Patton, Mark W. Clark and Omar N. Bradley, although he was junior to the other four.

In eulogizing him, Powell said, “The legacy of General Ridgway is universal, it’s timeless.” He added, “You see a long, devoted service to the nation, of duty, of honor, of country. No soldier knows honor better than this man.” Ridgway added to his legend as commander of the United Nations forces in Korea during the Korean War. He took command while the U.S. forces, along with Allied troops, were in a fighting retreat from the Manchurian Border ahead of China’s forces in Dec 1950. He is credited with restoring “fighting spirit and pride” to the Allied forces. And the forces soon resumed an offensive posture. “General Ridgway and his men stood like rocks,” Powell said. “He brought the pride back to the troops of the Army, he restored their dignity, he put them back on top. He fought hard to keep Army proud and ready to fight.” A 40-man representative enlisted force and numerous 82nd Airborne Division officers came to ceremonies to help lay to rest the man who boosted the Division to Airborne status and commanded it from the invasion of North Africa to the Normandy Invasion. They were at rigid attention as the 3rd U.S. Infantry (The Old Guard) Salute Battery fired final 17-gun salute to Ridgway.

March 3, 1895-Jul 26, 1993.

Section 7 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard