U.S. Department of Defense

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs)

News Release

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 0058-08

January 23, 2008

DoD Identifies Army Casualty

The Department of Defense announced today the death of a soldier who was supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

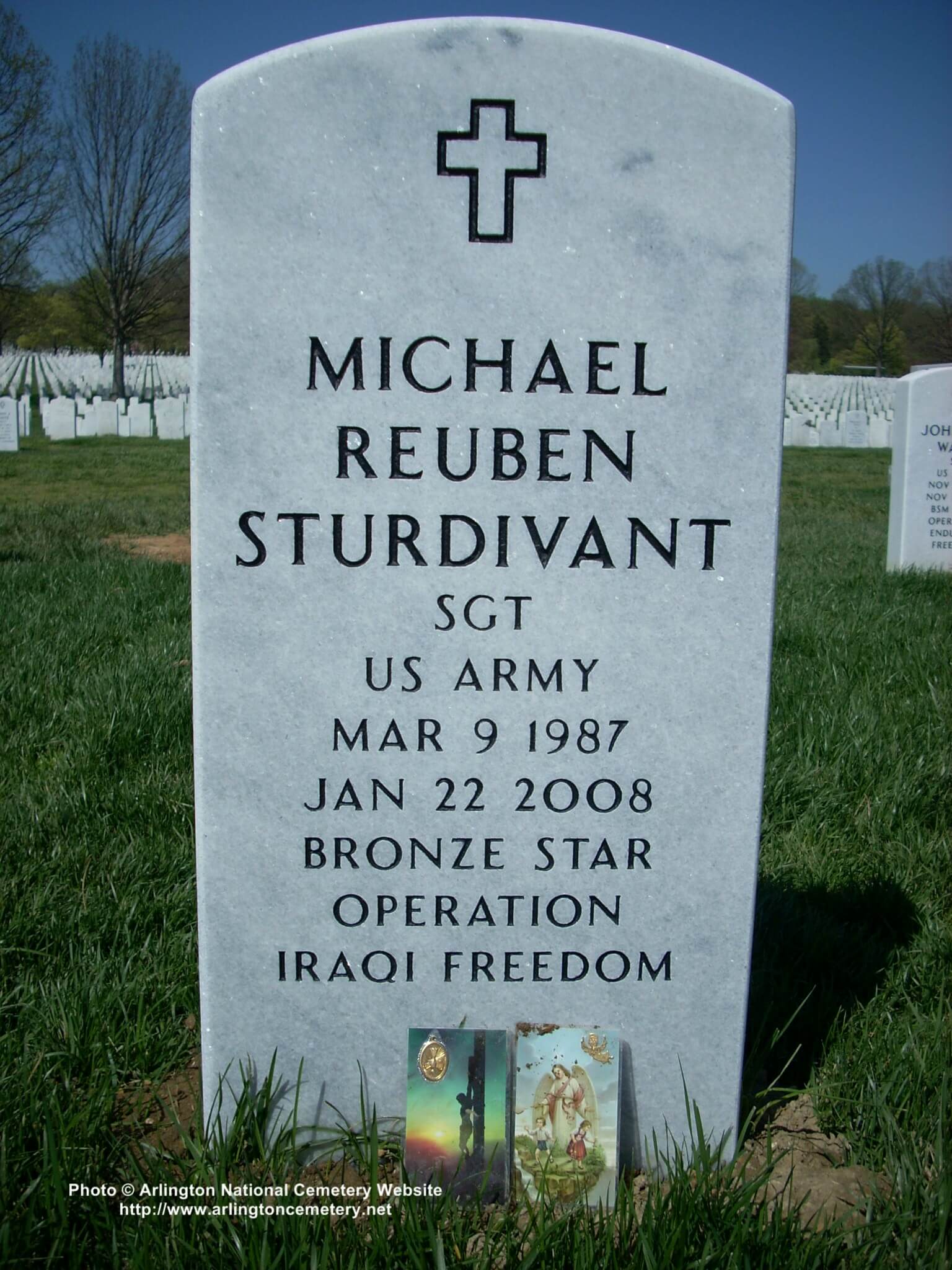

Sergeant Michael R. Sturdivant, 20, of Conway, Arkansas, died January 22, 2008, in Kirkuk, Iraq, of injuries sustained in a vehicle accident during convoy operations. He was assigned to the 431st Civil Affairs Battalion, U.S. Army Civil Affairs & Psychological Operations Command (Airborne), Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Memorial planned for fallen soldier

By JOE LAMB

COURTESY OF THE LOGCABIN. NET

Conway, Arkansas

February 1, 2008

A memorial service for Sergeant Michael Sturdivant will be held at 10 a.m. on Feb. 9 at the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, located at 7000 John F. Kennedy Boulevard in North Little Rock, Arkansas.

Sturdivant was killed in Kirkuk, Iraq, on January 22, 2008. According to a U.S. Army news release, he was killed in a vehicle rollover during a convoy operation. He was two weeks away from the end of his tour of duty and would have been 21 in February.

He will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery on Thursday.

Sturdivant was a University of Central Arkansas student living in Conway before his deployment as a civil affairs sergeant assigned to the 431st Civil Affairs Battalion, stationed in North Little Rock. The 431st is a subordinate unit of the U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command (Airborne) of Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

“Michael was so bright,” Sturdivant’s grandfather, David Clark of Clinton, said. “He was always very, very bright and as analytical as the dickens. He was playing chess when he was 7.

“He always had a little quiet space around him,” Clark continued. “When he needed to think, and he thought a lot, he pulled the shade down and had this quite space around him and it was hard to get to him through that sometimes.”

Sturdivant earned the rank of Eagle Scout with North Little Rock’s Troop 427. He was an assistant scout master for the troop and a member of the Order of the Arrow until the time of his deployment.

“Michael was a student and he loved scouting,” Clark said. “He worked so hard at getting all the badges and all those things. Michael had a good sense of humor, but mostly he was always a guy that liked to learn things and he liked to teach things. I think Michael was a natural leader and a natural teacher. So many people have tremendous amounts of information and ability that they never use, but Michael used his, very quietly in some cases, but he always used what he had.

“I regret that I didn’t have a lot of time with him.”

Sturdivant’s grandmother, Betty Lou Clark, said she remembers him as “a delightful little boy.”

“I don’t now where to start,” she said. “He was always very bright, very verbal. He talked very clearly and always had a very nice vocabulary when he was so young. His words were very crisp I don’t remember him ever talking baby talk. I’m sure he did, but I just remember him talking so well so early.”

In his military career, Sturdivant earned the Army Achievement Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Iraq Campaign Medal, Global War on Terrorism Service Medal, Armed Forces Reserve Medal with “M” device, NCO Professional Development Ribbon and the Army Service Ribbon. He was the 3,931th U.S. serviceman to die in Iraq.

For his Eagle Scout project, Sturdivant designed and oversaw the construction of several bridges along a walking path at Woolly Hollow State Park near Greenbrier.

He became a Catholic at North Little Rock’s Immaculate Conception Catholic Church shortly before his deployment. His parents, Steve and Cheryl Sturdivant, reside in Bonner, Montana.

7 February 2008:

Cheryl Sturdivant talked to her son, Michael, just about every day over the last year.

They talked over the computer, her from home, him from wherever his battalion happened to be in Iraq. Sometimes he’d be on a mission and out of touch for a few days, but she somehow kept her worries at bay.

After all, her husband, Victor, had been a police officer in North Little Rock, Arkansas. She was accustomed to the stress of potential violence to her loved one and had come to terms with it.

“The reality of life is that you can be killed at any time doing anything,” Cheryl Sturdivant said Tuesday by phone from her home in Bonner, where Cheryl and Victor recently moved from Arkansas. “You can’t live your life in fear. That’s not living.”

Michael was in Iraq because he wanted to be. He deeply believed he was helping people, and he told his mother often of the appreciation the Iraqi people showed him.

About two weeks ago, the 20-year-old Army sergeant was riding in a military convoy in Kirkuk. Michael was in the gun turret as the vehicle moved along a deeply rutted road.

A United Nations observer was also in the vehicle and was moving up to take a look from the turret when the truck hit a huge rut that flipped the vehicle.

“What we’ve been told is that Michael was doing everything he could to get this person back down into the truck as it rolled over,” Cheryl said.

A handful of the soldiers were hospitalized after the crash, and the U.N. observer survived only to die three days later from his injuries.

The lone fatality the day of the wreck was Michael Sturdivant. He was less than two weeks away from coming home alive.

“I know he’s gone, but I really need to see him to just know it down deep,” Cheryl Sturdivant said.

On Wednesday, Cheryl, Victor and their five children flew off to Virginia, where Michael will be buried Thursday at Arlington National Cemetery.

“He died doing what he loved to do, helping people and feeling like he was improving their lives,” Cheryl said. “That’s what really made him happy.”

He was always a good boy, striving hard to make the “right” choice even when it was inconvenient.

He was reading and doing math by the time he went to kindergarten, so his mom decided to home-school him. That worked so well he was ready for college by 17.

The family had moved to the small town of Clinton, Arkansas, when Michael was 5, then moved again to North Little Rock in 1998. Victor worked there as a police officer, while Cheryl taught their children.

“Michael was just brilliant, so excited about learning and growing,” she said.

During those early years, Michael joined the Boy Scouts and eventually worked his way up to Eagle Scout.

“He just loved everything about it, from being outdoors to the discipline it takes to master those skills,” his mother said.

When his high school friends turned to drugs and alcohol, Michael abstained. In fact, he protested.

“He really felt like it was something he should make a stand about, even if it made him unpopular,” Cheryl said. “I know a lot of those kids feel like he played a role in saving their lives now.”

Michael went to college at 17, but the family was also at work trying to get him into the U.S. Naval Academy. He aced the entrance exam, but eventually decided not to go because he didn’t want a career in the military. Instead, he enlisted in the Army, to do one tour of duty, and was assigned to the 431st Civil Affairs Battalion.

“I was a little disappointed, but like everything he did, he’d really thought it through and made a good choice, so I supported him,” Cheryl said. “He was going to come back from his tour of duty, go back to college and major in math and teach.”

He also had a girlfriend, Melinda, he couldn’t wait to see and planned to one day marry.

“She’s just taking this so hard,” Cheryl said.

So are the Sturdivants. But they are comforted by what they see as the rightness of Michael’s efforts. The justice Cheryl Sturdivant sees in the American involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq is not a justice born of empire building or oil or the replacement of Islam with Christianity.

For her, it’s about facing down tyranny in whatever incarnation it takes – Saddam Hussein or the Taliban.

“Our family believes that evil prospers when good men do nothing,” she said.

When her son went off to Iraq, Cheryl enrolled in a world religions class at an Arkansas college.

She found out that she had some disagreements with some of the world’s religions, but that didn’t bother her a bit.

“That’s what’s great about America, that you can do as you please, believe as you please,” she said.

But she also learned about the brutal face of religious fanaticism, be it Muslim or Christian or any other religion.

“The more I learned about the Taliban, especially the way they treat women, the more I was convinced that there is a role for us there,” she said. “It’s not to install a Christian democracy. It’s to give those people a life where they don’t have to hide in their homes from the fanatics.”

That’s what Michael felt like he was doing overseas. And although he’s gone, his mother believes that spirit lives on in those who are still risking their lives for the freedom of others.

“The whole thing is tragic, and I feel so bad for the mothers here who’ve lost their children, but also for the mothers there who are afraid to go out of their homes, afraid to let their children out of their homes,” she said.

Then she started to cry for all the children.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard