Courtesy of the United States Marine Corps

SERGEANT MICHAEL STRANK, USMC (DECEASED)

Michael Strank, participant in the famous flag raising on Iwo Jima, was born in Czechoslovakia n 10 November 1919, the son of Vasil and Martha Strank, natives of Czechoslovakia (his father was also known as Charles Strank), and raised at Conemaugh, Pennsylvania. He attended the schools of Franklin Borough, Pennsylvania, and graduated from high school in 1937. He joined the Civilian Conservation Corps where he remained for 18 months and then became a highway laborer for the state.

Michael Strank enlisted in the regular Marine Corps for four years at Pittsburgh on 6 October 1939. He was assigned to the Recruit Depot at Parris Island where, after completing recruit training in December, Private Strank was transferred to Headquarters Company, Post Troops, at the same base.

Transferred to Provisional Company W at Parris Island on 17 January 1941, Strank, now a Private First Class, sailed for Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, arriving on the 23d. Strank was assigned to Headquarters Company, 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Brigade (on 1 February, the 1st Marine Brigade was redesignated the 1st Marine Division). On 8 April, now assigned to Company K, he returned to the States and proceeded to Parris Island. In September, Strank moved with the division to New River, North Carolina (now known as Camp Lejeune). He was promoted to Corporal on 23 April 1941, and was advanced to Sergeant on 26 January 1942.

With the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, early in April 1942, he journeyed cross-country to San Diego, California, from whence he sailed on the 12th. On 31 May, he landed on Uvea, largest of the Wallis Islands.

In September, after a short tenure with the 22d Marines, he was transferred to the 3d Marine Raider Battalion, also at Uvea. With the raiders, he participated in the landing operations and occupation of Pavuvu Island in the Russell Islands from 21 February until 18 March, and in the seizure and occupation of the Empress Augusta Bay area on Bougainville from 1 November until 12 January 1944. On 14 February, he was returned to San Diego for rest and reassignment.

On return from leave, Sergeant Strank was assigned to Company E, 2d Battalion, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division. After extensive training at Camp Pendleton and in Hawaii, Strank landed on Iwo Jima on 19 February 1945.

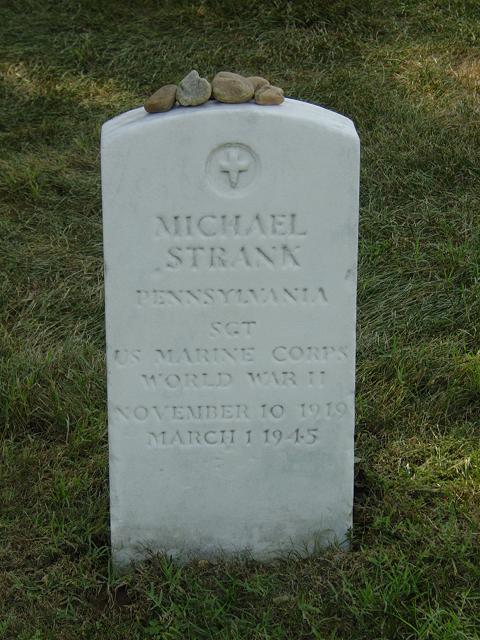

After the fall of Mount Surbachi, he moved northward with his unit. On 1 March, while attacking Japanese positions in northern Iwo Jima, he was fatally wounded by enemy artillery fire. He was buried in the 5th Marine Division Cemetery with the last rites of the Catholic Church. On 13 January 1949, his remains were reinterred in Grave 7179, Section 12, Arlington National Cemetery.

Sergeant Strank was entitled to the following decorations and medals: Bronze Star, Purple Heart (awarded posthumously), Presidential Unit Citation with one star (for Iwo Jima), American Defense Service Medal with base clasp (for his service in Cuba before the war), American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with four stars (for Pavuvu, Bougainville, Consolidation of the Northern Solomons, and Iwo Jima), and the World War II Victory Medal.

He was the oldest of the six American soldiers who raised the American flag over Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima, in the midst of the bloody fighting there. He was subsequently killed on Iwo Jima by enemy artillery fire.

His body was originally buried on Iwo but was subsequently moved to Section 12, Grave 7179, of Arlington National Cemetery on January 19, 1949.

One of Washington’s premier landmarks is the world’s largest statue, an immense sculpture in bronze, weighing 100 tons and reaching a height of 110 feet. It depicts six Marines–each figure about 32 feet tall–hoisting an American flag on the island of Iwo Jima, a part of the prefecture of Tokyo, located in the Pacific Ocean 650 miles from the Japanese mainland.

The monument memorializes one of the final battles of the 20th century’s Second World War and has become, in the words of an academician, “one of the most charged and powerful cultural symbols of patriotism to mainstream Americans.” It was copied from a photograph made in February 1945 by Joe Rosenthal, an Associated Press photographer. The struggle ended a month or so later with more than 25,000 American Marines dead or wounded. The Japanese garrison of 22,000 was annihilated but for a few prisoners.

The flag-raising image, captured by Rosenthal in 1/400th of a second, had an adrenaline effect on a public tiring of war and haunted by fear that the approaching invasion of Japan would be Armageddon. Critics hailed the picture as a transcendent work of art. It inspired the sale of billions of dollars in war bonds and gave sculptor Felix de Weldon the blueprint for the huge statue that now looms alongside the Arlington National Cemetery. It made Rosenthal famous, brought sculptor de Weldon both fame and wealth, and gave the Marines a semi-religious institutional icon, a triumphant metaphor for the very soul of the Corps.

What has been lost in all this is any collective memory of the six boys who raised the flag and then, after an instant of notoriety, passed into the void of anonymity that, with few exceptions, awaits us all. Who were they? What happened to them?

The most recent of the many books inspired by the battle and by Rosenthal’s sublime image is Flags of Our Fathers, by James Bradley. It is described in a jacket blurb by the prolific military historian Stephen Ambrose as “the best battle book I have ever read.” Others may view it in that light, but that was not the author’s purpose. His principal aim was to rescue these forgotten boys–one of them his father–and transform them from “anonymous representative figures” into individuals.

His profiles of them resemble a cast from the paintings of Norman Rockwell, unfamous, un-celebrified, “ordinary” Americans: —Mike Strank, an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, brought to America in infancy by his father, who had found work digging coal in Pennsylvania for Bethlehem Steel.

Ira Hayes, a “non-citizen” and immigrant of sorts in his native land, a Pima Indian born on a small cotton farm in the Gila River reservation in Arizona–geography his people had occupied for more than 2,000 years.

Harlon Block, born on a farm in the Rio Grande valley of Texas, a superb athlete raised in a pacifist Seventh Day Adventist home where killing and even the possession of weapons were forsworn. “It is doubtful,” Bradley writes, “that in his short life Harlon Block ever kissed a girl.”

Franklin Runyon Sousley, a good old hillbilly boy from Eastern Kentucky, a practical joker who, it was said, would “fight a running sawmill.” His father died when he was 8 years old, leaving him as the man in the family.

Rene Gagnon, child of French Canadian mill workers in Manchester, N.H., a shy, self-conscious “mama’s boy” who “never chummed with the guys” and, like his parents, faced a lifetime in a factory until the Marines got him in 1943.

Jack Bradley, father of the author of this book, an altar boy from a devout Catholic household in Antigo, Wis. His high school ambition (fulfilled after the war) was to be a funeral director, a counselor and friend to the bereaved. He joined the Navy to avoid combat, wound up as a medical corpsman with the Marines and came home with a Navy Cross, an honor unrevealed to his family until after his death.

They were teenagers, Bradley writes, “scarcely out of boyhood when they enlisted. Their lives up till then had been kids’ lives: hunting, fishing, paper routes, the movies, adventure programs on radio . . . first wary contacts with girls . . . Most of them were poor. The Great Depression ran through their lives.” They grew up fast in the war, discovering that doing their duty to God and country involved unimagined pain, terrors and awful deeds.

On February 23, 1945, the fifth day of the battle, they raised the second of two flags planted that morning on the summit of Mount Suribachi, an extinct volcano that overlooked the landing beaches and had been made by the Japanese into a hellish nest of gun emplacements, pillboxes, fortified caves, tunnels and storage depots.

A week later their outfit, Easy Company, Second Battalion, 28th Marines, joined an assault on another ugly, heavily fortified terrain. They came under heavy sniper fire. Mike Strank, now a sergeant, squad leader and father figure to Hayes, Block and Sousley, led them to cover under a rocky outcropping. A shell, almost certainly from an American destroyer lying offshore, exploded and tore out Strank’s heart. Harlon Block took over the squad. A few hours later a mortar round sliced him from groin to neck. As his intestines poured out on the ground he cried out: “They killed me.”

Easy Company moved on, losing men daily. Jack Bradley, the corpsman, was wounded by shrapnel and flown out to a hospital in Guam. Sousley was shot by a sniper. Someone shouted: “How ya doin’?” Sousley replied: “Not bad. I don’t feel anything.” Then he fell and died.

Ira Hayes left Iwo Jima unwounded and nine months later was a civilian again, leaving behind in a mass graveyard on the island the best friends he ever had — Mike and Harlon and Franklin. Back home he found menial jobs on the reservation — cotton picking and other day labor work. He became a drifter, drank a lot, was in and out of jail and died in an abandoned hut on the reservation after an all-night poker game in January 1955, just short of 10 years after the flag-raising. He was 32 and got the biggest funeral in the history of Arizona.

Rene Gagnon survived the war unharmed, tried to exploit his brief fame as a flag-raiser but never “made it” out of the New Hampshire rut into which he was born. He was a janitor at a tourist home when he died in 1979 at the age of 54. Jack Bradley died in 1994, patriarch of a large family, revered town father in Antigo and proprietor of one of the largest funeral businesses in Wisconsin.

None of their names is on the monument. You can find out more about them in James Bradley’s fine book.

Richard Harwood, a veteran of the Iwo Jima battle, is a former reporter, editor and columnist for The Washington Post.

USMC CASUALTY REPORT:

Date: 12 March 1945

Card: No

CAS NO: 024761

NAME: Strank, Michael

Rank: Sgt

Class: USMC

IDENT: 275228

ORGANIZATON: Co E 2nd Bn 28 Mars

Type of Casualty: KIA

Area: Pac

Date of Casualty: 1 Mar 45

DATE APPT/ENLIST: 6 Oct 39

Date of Birth: 10 Nov 19

Place of Birth: Conemaugh, Pa.

Legal Residence: Johnstown, Pa.

Prior Ser: No

Misc. Sta:

Marital: S

Next of Kin: Mr. and Mrs. Charles Strank

Relation: Parents

Address:

Beneficary: DGB: Mrs. Martha Strank Mother

Rear Of Card:

Burial Bulletin #9, fr HQ, 5th Mar Div (reinf) dtd 3 Mar 45 rec’d 17 Mar 45 (bm)

Service Book Received: June 14, 1945 (MK)

Father *Mr. Vasil Strank, req remain ret for burial in Arlington Nat Cem, Ft. Myer, Va. Appl dtd 5 Nov 47 (MEG)

Premanently reburied 13 Jan 49 in Grave #7179, Sec. 12, Arlington Nat Cem, Ft. Myer, Va. (GEO)

(From the collection of M. R. Patterson)

Marine Raised Flag at Iwo Jima And Profile of Immigrants’ Service

By Ben Hubbard

Courtesy of The Washington Post

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

The 1945 photograph of six U.S. servicemen raising the flag over Iwo Jima won a Pulitzer Prize, served as the model for the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington County and has become one of the most enduring images of World War II.

But until this year, the U.S. Marine Corps wasn’t aware of the immigrant background of one of the men in the photograph, Marine Sergeant Michael Strank, thinking he was born in Pennsylvania. He was born in Czechoslovakia.

The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services tried to rectify the oversight yesterday by presenting Strank’s younger sister, Mary Pero, 75, with a certificate of citizenship in a ceremony in front of the statue that bears his likeness. Pero accepted the certificate on his behalf, smiling proudly in front of the towering bronze statue.

Mary Pero says she knew her brother Michael Strank was a citizen, “but I didn’t realize he didn’t have any papers.”

During the ceremony, Jonathan Scharfen, acting director of CIS, said Strank hailed from “a long line of famous American immigrants who served their county in a time of war.”

Strank was born in Jarabenia, Czechoslovakia, and immigrated to the United States in 1922, where he lived with his family in Conemaugh, Pa. Strank became a citizen when his father, Vasil, was naturalized in 1935, although the younger Strank never received a certificate. Strank’s mother, Martha, was naturalized in 1941.

After graduating from high school and spending a year and a half in the Civilian Conservation Corps, Stark joined the Marines and served on various bases in the United States and in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, before sailing for combat in the Pacific in 1942.

Four days after landing on Iwo Jima, Strank, four other Marines and a sailor raised the flag atop Mount Suribachi. Strank’s sister recalled seeing the image in her local paper, although at the time she had no idea her brother was one of the men.

Almost 7,000 U.S. military personnel, mostly Marines, died in the 36-day assault, and nearly 20,000 were wounded, making it one of the war’s bloodiest fights. Strank, 25, died in combat a week after the flag raising, and Pero, who lives in Davidsville, Pa., remembered that her mother knew what had happened as soon as she saw the man with the telegram approaching their house.

The family didn’t learn Strank was one of the men in the photo until after his funeral, Pero said, when reporters called their home. In 1949, Strank was reinterred in Arlington National Cemetery.

The Marine Corps was unaware of Strank’s immigrant history until this year, Scharfen said, when a Marine security guard at the U.S. Embassy in the Slovak Republic who was researching Strank’s background found no record of Strank being a U.S. citizen. This year, he filed an application for posthumous naturalization for Strank, Scharfen said.

CIS investigated, finding that Strank had been naturalized but never received a certificate, Scharfen said.

Marine Sergeant Strank was posthumously awarded a certificate of U.S. citizenship

He said Strank’s story represents the contributions that immigrants have made to the United States throughout its history, adding that new immigrants can apply for citizenship after their first day of military service. He said almost 40,000 people have become citizens this way since the rule was created in 2001.

After the ceremony, Pero posed for photos in front of the monument with her husband and six other family members. The family had always known Strank was a citizen, she said, “but I didn’t realize he didn’t have any papers.”

“I feel so proud,” she said, gazing up at the bronze face of her brother. “It makes me feel that this is history.”

She pointed to her 9-year-old grandson, Tommy Pero, who carried a black-and-white photo of Strank. “I think about as he grows up and has a family,” she said, “this will all still be here.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard