From a press report: 7 March 2003:

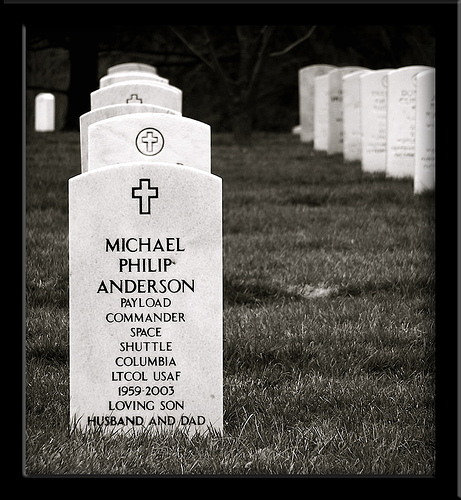

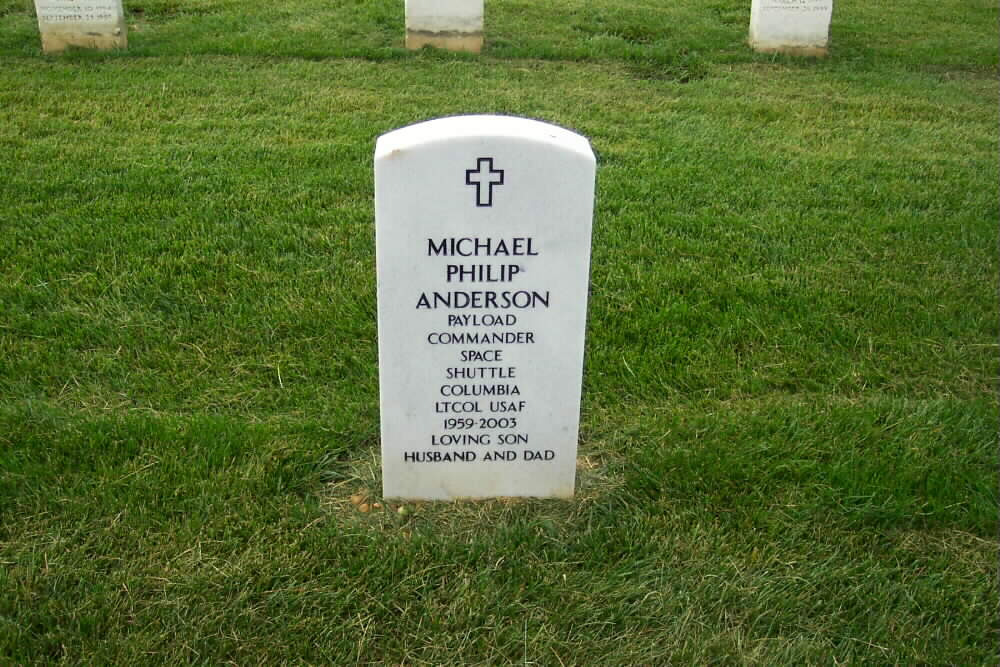

Columbia mission specialist Anderson buried at Arlington

Shuttle crew member Michael P. Anderson had tried to prepare his daughters for his darkest hour, should it come aboard the Columbia. This week, one hugging a teddy bear, they helped lay him to rest.

Anderson, who died February 1, 2003, was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on Friday a few steps from the grave of Dick Scobee, the commander of the shuttle Challenger, which exploded 17 years earlier.

A blustery wind whipped the more than 100 mourners at the hilltop grave site, where Anderson, 43, was given full military honors.

An Air Force Lieutenant Colonel and pilot, he had tried to prepare those close to him for this moment.

“If this thing doesn’t come out right, don’t worry about me; I’m just going on higher,” Anderson is said to have told his minister just before leaving on his second and final visit to space aboard Columbia.

And before blasting off on his second and final space flight, he tried to warn Kaycee, 9, and Sydney, 13, of “all the things that could happen,” mother-in-law Mabel Hawkins told The Columbian newspaper of Vancouver, Washington.

With official funeral duties over and a visit with President George W. Bush and his wife, Laura, still ahead, the graveside service became personal.

One by one, a dozen family members transferred single red roses from their own fingertips to the top of Anderson’s silvery casket.

Anderson had wanted his job since childhood in Spokane, Washington. His sense of wonder took him from there to the University of Washington and Creighton University and pilot training in the Air Force.

By the time NASA selected Anderson in 1994 to train as one of its few black astronauts, he had become an instructor pilot and tactics officer in the 380 Refueling Wing at Plattsburgh Air Force Base.

He visited the Mir space station (news – web sites) in 1998 and afterward declared to his wife, Sandra: “I’m a lifer. I want to go back.”

Mourners wiped away tears as they watched Air Force and NASA officials carry out their official burial duties.

A KC-135 Stratotanker — refueling boom extended — overflew the site in a tribute to Anderson, the same model he piloted as an instructor before taking his NASA assignment in 1995.

Air Force Secretary James G. Roche and NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe presented Anderson’s widow, Sandra, with the Defense Distinguished Service and the NASA Space Flight medals.

Out of the media’s earshot, Lieutenant Colonel Derek Green delivered a brief eulogy, and Chaplain Colonel Richard Hum conducted a short graveside service.

A seven-member firing party rendered a “volley of three” shots in tribute, followed by the sounding of “Taps.”

An Elegy in Air Force Blues

With Martial Precision and Polished Poise, Astronaut Is Laid to Rest

The making of a hero’s funeral is as precise as death is random, a shadow ritual behind the ritual, sorrow choreographing its own secret ballet.

It begins before the first fire of dawn casts a pearly glow over the tombstones at Arlington National Cemetery, before the gates open and the tour buses commingle with hearses, before the ruffle of funeral drums or the rumble of flyovers.

It is a world where pocket mirrors control combat planes, while comfort is taken in tradition and history, and caskets of men who rode rocket ships are borne to the grave by horse-drawn wagons that creak on their wooden wheels.

In their stalls at the Old Guard Caisson Platoon, matching teams of horses, black and dapple-gray, nicker and chuff as the first soldiers arrive at 4 a.m. to prepare for the day’s funerals. Six yesterday with full military honors; Lt. Col. Michael Anderson’s was scheduled for 1 p.m. The gray team would pull the fallen shuttle astronaut’s coffin on the black artillery caisson.

“You already had your grain this morning,” Sgt. James Jones chides a horse named Gerry, who has his feed bucket in his mouth and is thrusting it imploringly toward the 21-year-old lead rider. As more sleepy soldiers report for duty, the gray team clops one by one to the shower room to be hand-washed and dried before getting saddled. Clyde is the escape artist, famed for slipping his halter and wandering off; Salty will lunge for anyone wearing white. The barn is freezing, and steam rises in vapors off the horses’ flanks.

While the horses are bathed, the brass rails of the caisson are polished with Pledge, and the platoon sergeant, Larry Driscoll, checks his computer for the day’s dress code. Overcoats today, but regular service caps instead of the furry ones with earflaps, which the honor guard and 50 foot soldiers will be wearing. “What brainiac came up with that?” he wonders aloud. “The ambient temperature is 23 degrees out there.” The earflaps may look “ridiculous,” he allows, but at least the riders stay warm. Driscoll heads back to the shower room.

“Get a blanket for Salty, he’s shivering,” he orders. A soldier jogs off, then comes back empty-handed.

“The blankets are being professionally cleaned now,” he explains.

“I want a blanket for the damn horse!” Driscoll thunders. The soldier returns this time with a blanket pilfered from the black team.

In the tack room, the soldiers dip bare fingers into brass polish and rub it into the fittings on the black leather saddles and stirrups. Everything must gleam before they leave the barn. By 7 a.m., there will be time for breakfast in the chow hall, then a last-minute steaming of uniforms in the pressing machine before men and horses alike are dressed and ready to head into the cemetery.

Sunrise is Erik Dihle’s favorite time at Arlington, where he has overseen the grounds for nearly two decades, a horticulturist who can tell at a glance that a white oak is 300 years old or that the first of the 15,000 bulbs planted each year are ready to pop up. For a week before the Anderson funeral, Dihle focused on removing snow from Section 46, where members of the Columbia crew will be buried alongside fallen astronauts from the Challenger. Nearly an acre of snow has been cleared from 46, but the ground has been too saturated to dig a grave; the backhoes would chew deep ruts, which cemetery officials don’t want for such a high-profile funeral. Too muddy, too rough and ugly. No hole will be dug until the service is over and the mourners have left.

Five hours before the Anderson funeral, Dihle is inspecting the site again, this time with cemetery Superintendent John Metzler. A coco mat leads from the sidewalk to the grave site, but the ground still sinks underfoot. Metzler orders plywood planks to place under the mat. Dihle stoops to pick up stray twigs from the dead grass; the trees and shrubs on this small plateau were pruned and freshly mulched the day before. These same grounds will be beautiful come spring, when the turf greens up and the double pink blossoms bloom on the nearby Japanese cherry. But today, the landscape remains in winter’s harsh grip, and a cold wind is starting to whip through the naked trees.

At noon, the busloads of Air Force troops in their dress blues assemble in Jackson Circle, over the hill from Section 46. The eight pallbearers rehearse with an invisible casket. The Air Force band warms up. The honor guard runs through its showing of the colors, each of the 102 streamers on the Air Force flag representing a battle fought.

Maj. Dean Wright, a strapping pilot from Langley Air Force Base, heads off to find a hiding place where he can signal in the KC-135 tanker that will perform the flyover honoring Anderson, who flew the same type of plane early in his military career, before becoming an astronaut. Armed with a radio and a 30-page mission booklet with detailed instructions, weather information and map coordinates, Wright also carries a pocket mirror to catch the sun and flash the cortege’s location to the pilot 1,000 feet above.

Wright’s wife and 4-year-old son, Jack, have come along today to pay their respects to Anderson, and the boy tugs at his mother’s sleeve as the hearse bearing Anderson’s coffin pulls up alongside the waiting caisson.

“Mommy, where’s the astronaut?” he wants to know.

She nods toward the flag-draped coffin.

The mourners line up in the road. Anderson’s widow, Sandra, holds the mittened hands of daughters Sydnee, 11, and Kaycee, who is 9. The girls both clutch teddy bears and stare straight ahead.

The pallbearers place the casket on the polished caisson as the band begins to play “God Bless America,” in slow, sorrowful time.

“Mommy, why are the little girls sad?” Jack asks in a small whisper.

The tanker appears overhead, everyone turning their faces to the sky to watch it pass. The chaplain leads the funeral march, the matched horses prancing 24 paces behind, and the mourners follow on foot.

In the silence they leave behind, a small boy’s voice is more urgent now.

“Where is the astronaut? Where is he?”

A few minutes later, the cortege rounds the corner in front of the amphitheater where eternal vigil is kept over the Tomb of the Unknowns. Anderson’s widow and children take their places in the front row of folding chairs, along with his parents, Bobbie and Barbara Anderson. His father gently pats his mother’s knee as she wipes away tears.

The 43-year-old payload specialist is posthumously awarded three medals for his distinguished service to his country, and top NASA and Air Force brass kneel tenderly on the sodden ground to comfort his bewildered children.

He is eulogized by his best friend, who wears Air Force blues and speaks of Anderson’s deep faith. Chaplain Richard Hum, a colonel himself, notes that Anderson had asked his church congregation back home in Houston to pray that his space mission be used “for the glory of God.”

“It is here that for nearly 150 years America has chosen to place their heroes,” Hum tells the 200 mourners.

Beneath the ancient oaks and delicate cherry trees are presidents, and poets, soldiers who rode to battle on horseback, explorers who conquered the North Pole, men who walked on the moon. There are 17 astronauts in all now.

The crack of a rifle salute pierces the funeral hush, and the drums beat fast and low like a quickening heart.

And as the plaintive notes of taps carry on an icy wind, the remains of space shuttle astronaut Michael Philip Anderson are laid to rest in the hallowed ground where heroes sleep at Arlington National Cemetery.

Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Michael P. Anderson, the payload commander on board the Space Shuttle Columbia when it broke apart in flames last month over Texas, was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery yesterday.

As the Air Force Band played “Amazing Grace,” the honor guard lifted Colonel Anderson’s casket off the horse-drawn caisson and carried it to the burial plot. Colonel Anderson’s wife, Sandra, his two young daughters and his parents followed closely behind as a crowd of family and friends watched, saluting or holding their hands over their hearts.

NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe wept as he watched Mrs. Anderson and her daughters place roses on Colonel Anderson’s casket.

Many wiped tears from their eyes as they remembered Colonel Anderson as a man of faith who was committed to his relationship with God and his family more than to his career.

Colonel Anderson’s friend, Lieutenant Colonel Derek Green, said Anderson “gave new meaning to the phrase, ‘If I could be like Mike.'”

“His accomplishments as a Christian, as a father, as a husband and a friend far surpassed his achievements as an astronaut,” Colonel Green said.

Chaplain Colonel Richard Hum tried to comfort Mrs. Anderson and her daughters during the eulogy.

“I know you must have mixed feelings of pride and sorrow today,” he told Mrs. Anderson. “Your husband was a remarkable man. Our country grieves with you.”

“I know you must be hurt and confused right now,” Colonel Hum told Anderson’s daughters. “I want you to know your dad loved you very much.”

As Colonel Hum read a passage from the Bible that talked about God working all things for the good of those who love him, Anderson’s mother, Barbara, slowly nodded her head in affirmation.

Colonel Anderson, 43, received a full military funeral, which was attended by about 200 family and friends. Secretary of the Air Force James G. Roche and General Lance W. Lord, commander of the Air Space Command at Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado, also attended.

The Air Force conducted a flyover and the honor guard fired a three-round volley in salute.

Anderson was born in Plattsburgh, New York, but considered Spokane, Washington, his hometown.

He was the son of an Air Force man and grew up on military bases. He was flying refueling squadrons for the Air Force when NASA chose him in 1994 as one of only a handful of black astronauts. He traveled to Russia’s space station Mir in 1998, and he was in charge of Columbia’s dozens of science experiments.

Anderson is the fifth of the seven Columbia astronauts to be buried. Navy Commander Laurel B. Clark, 41, of Racine, Wisconsin, and Navy Captain David M. Brown, 46, of Arlington, will be buried at Arlington on Monday and Wednesday, respectively.

ARLINGTON, Virginia – One month and six days after the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated during re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, Lieutenant Colonel Michael Anderson, one of the seven crew members who died, was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Anderson, 42, served as Columbia’s payload commander.

His 9-year-old daughter, Kaycee, clutched a brown teddy bear during the service. Her sister, Sydney, 11, looked straight at the coffin or down at the ground most of the time. Anderson’s wife, Sandra, worked to maintain a sad smile, while the astronaut’s mother and father simply cried.

The graveside service lasted just under an hour.

It began with a drum beat. Then gray and white horses made their way down a curving path, pulling a tall, black antique-like wagon carrying Anderson’s flag-draped coffin. A band played “Amazing Grace” as members of a military color guard lifted the casket onto their shoulders and carried it to its resting place.

After words from various speakers, Sandra Anderson accepted a Distinguished Service Medal for her husband’s service to the military and NASA.

Then a 21-gun salute broke the silence, followed by the lonely sound of a single trumpet playing Taps.

Members of the color guard then lifted the American flag that had been draped over Anderson’s coffin, folded it and handed it to the widow.

His parents dotted their eyes with a tissue as another American flag was given to them.

The ceremony drew to a close with the girls and their mother each placing a single, long-stemmed red rose on top of the silver casket. Other friends and family followed, offering condolences as they left.

In all, the seven astronauts left behind 12 children, six spouses, 13 parents and 20 brothers and sisters.

Remains of the astronauts were gathered, in pieces, from the wide area in which debris from the shuttle landed and were identified through DNA analysis.

Michael P. Anderson left this Eastern Washington city for a career in space in 1977, but when he died in the fiery destruction of the space shuttle Columbia, Spokane grieved.

Anderson was Spokane’s astronaut.

He grew up and went to high school in neighboring Cheney, then on to the University of Washington in Seattle before leaving the state for the Air Force, graduate school and NASA. Each step of his career was watched with pride by family and friends back home.

A year after the shuttle disaster, his legacy continues to grow.

Anderson, 43, an Air Force Lieutenant Colonel, was among seven astronauts aboard the shuttle when it disintegrated over Texas minutes before its scheduled landing February 1, 2003.

Since his death, Anderson has been honored by having a 17-mile stretch of highway, an elementary school and a high school math and science wing named for him.

“I just think those are very, very nice tributes,” Anderson’s wife, Sandy, said by telephone from her home in suburban Houston. “The whole Spokane community has helped us and honored the memory of my husband.”

She wrote an open letter to the pupils of the former Blair Elementary, which was renamed this month Michael Anderson Elementary.

“I was thrilled they read it to the students,” she said. “I couldn’t think of a more fitting tribute than to have his name at an elementary school where kids learn they can … achieve their goals, and to set high goals.

“Even that strip of highway for me is a really neat thing,” she said. “Because I know that is a road that Michael traveled a lot.”

The 17-mile stretch of State Highway 904 linking Interstate 90 with Cheney was named for Anderson this year.

There’s also a proposal to name a planned Spokane science center for Anderson.

Anderson’s parents, Bobbie and Barbara Anderson, still live in Spokane. They plan to travel to Washington, D.C., for a February 2, 2004, unveiling of a monument to the Challenger astronauts at Arlington National Cemetery, where their son is buried.

“It makes us feel proud,” Anderson’s mother, Barbara, said recently. “He lived a life that would draw this kind of attention, and that people would want to do something, shows he was an honored person.”

Anderson was raised in the Spokane area while his father was stationed at nearby Fairchild Air Force Base in the 1970s.

The flag-draped casket of Lieutenant Colonel Michael P. Anderson, a crewmember aboard

the Space Shuttle Columbia, is delivered to its resting place at Arlington National

Cemetery by a U.S. Air Force honor guard, March 7, 2003.

The flag draped coffin of Columbia shuttle astronaut Michael P. Anderson is carried by the

U.S. Air Force honor guard during a funeral service at Arlington National Cemetery

in Arlington, Virginia, Friday, March 7, 2003.

The flag-draped casket of Lieutenant Colonel Michael P. Anderson, a crewmember aboard

the Space Shuttle Columbia, is carried to its grace site at Arlington National Cemetery

by a U.S. Air Force honor guard, March 7, 2003.

Sandra Anderson, center, wife of Columbia shuttle astronaut Michael P. Anderson,

carrying a family portrait, arrives with her two daughters, whose identity was withheld,

during a funeral service at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia,

Friday, March 7, 2003.

Sandra Anderson, right, widow of Columbia shuttle astronaut Michael P. Anderson,

receives the NASA Space Flight Medal from NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe, left,

during a funeral service at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, Friday, March

7, 2003.

NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe places his hand over his heart, during the funeral for

Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Michael P. Anderson, a crewmember aboard the Space Shuttle

Columbia, at Arlington National Cemetery, March 7, 2003.

General Lance W. Lord, commander of the Air Force Space Command, left, presents the United

States flag to Sandra Anderson, second right, wife of Columbia shuttle astronaut Michael P.

Anderson, during a funeral service at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia,

Friday, March 7, 2003.

Sandra Anderson (R) widow of Lieutenant Colonel Michael P. Anderson, a crewmember aboard

the Space Shuttle Columbia, receives the flag that was draped over Anderson’s coffin from

Air Force General Lance W. Lord (L), Commander of Air Force Space Command at Arlington

National Cemetery, March 7, 2003.

One of the daughters of Columbia shuttle astronaut Michael P. Anderson, who the family

refused to indentify, holds a teddy bear as she stands over her father’s coffin during a funeral

service at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, Friday, March 7, 2003.

Photos Courtesy of the Associated Press and Reuters Press Service

Department of Defense Photo

Michael P. Anderson, 43, a Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Air Force, was a former instructor pilot and tactical officer, and a veteran of one spaceflight. He served as Payload Commander and Mission Specialist 3 for STS-107. As payload commander he was responsible for the success (management) of the science mission aboard STS-107.

Anderson received a bachelor of science in physics/astronomy from University of Washington in 1981 and a master of science in physics from Creighton University in 1990.

Anderson, as a member of the Blue Team, worked with the following experiments: European Space Agency Advanced Respiratory Monitoring System (ARMS); Combustion Module (CM-2), which included the Laminar Soot Processes (LSP), Water Mist Fire Suppression (MIST) and Structures of Flame Balls at Low Lewis-number (SOFBALL) experiments; Mediterranean Israeli Dust Experiment (MEIDEX); Mechanics of Granular Materials (MGM); and the Physiology and Biochemistry Team (PhAB4) suite of experiments, which included Calcium Kinetics, Latent Virus Shedding, Protein Turnover and Renal Stone Risk.

Selected by NASA in December 1994, Anderson flew on STS-89 in 1998 – the eighth Shuttle-Mir docking mission. Prior to STS-107, Anderson logged over 211 hours in space.

Colonel Anderson was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery on 10 March 2003 (Section 46, Grave 1180-1). He is buried next to fellow Astronaut Captain Laurel Blair Salton Clark.

NASA Photo

From a contemporary press report:

SPOKANE. WASINGTON — Space shuttle astronaut Michael Anderson will get a hero’s burial on March 7, 2003, at Arlington National Cemetery, and a huge memorial service four days later in Spokane.

The memorial service will be at the 2,500-seat Spokane Opera House on March 11, his mother, Barbara Anderson, said this week. The service is at 11 a.m and will be open to the public.

Anderson “was a brave man who worked to achieve his dream and then shared his love for science and space with the children of our community,” Spokane Mayor John Powers said.

“The March 11 memorial service will provide our community an opportunity to recognize and celebrate the many contributions of Lieutenant Colonel Michael Anderson, and for us to support his family,” Powers said.

The city is waiving the normal rental charges for the Opera House, and the mayor’s office will pay for incidental costs of putting on the memorial, Powers’ office said.

Anderson, 43, listed Spokane as his hometown, even though he lived in the space program’s home base of Houston for several years. Anderson’s wife, Sandra, a Spokane native, and his two daughters are expected to attend.

Anderson was among seven astronauts who died when the Shuttle Columbia broke up during re-entry on February 1, 2003.

Governor Gary Locke will speak at the memorial, and the White House has been asked to send a representative.

Anderson served as Columbia’s payload commander, overseeing science experiments during the 16-day mission.

He first flew in space in 1998 aboard the shuttle Endeavour, and then returned to speak to several Spokane-area schools and community groups.

It’s doubtful that Michael Anderson, who despite being a high achiever was noted for his modesty, would have been comfortable with large memorials, those who knew him said. His parents often learned of his promotions in the U.S. Air Force through official newsletters or friends.

But memorials are coming anyway.

On Wednesday, the state Transportation Commission voted unanimously to rename state Route 904, which runs from Interstate 90 to Cheney, in Anderson’s honor.

Barbara Anderson, the mother of Columbia astronaut Michael Anderson raises her arms

in front of a portrait of her deceased son as husband Robert (obscured) puts a hand on

her in comfort during a spiritual song at his memorial service February 5, 2003 at

Grace Community Church in Houston, Texas. A joint memorial service was held at the

church for shuttle commander Rick Husband and fellow Grace Church congregant Anderson.

Remains of Columbia Crew Recovered

While forensics experts said the fragmentary remains could be genetically identified despite the craft’s disintegration 39 miles overhead, details about exactly how the seven astronauts died and how quickly could be elusive.

“We found remains from all the astronauts,” Bob Cabana, director of flight crew operations, said Sunday. “It’s still in the process of identifications, and we’re working closely with representatives of the Israeli government to ensure that everything is done properly.”

Astronaut Ilan Ramon was an Israeli fighter pilot. That country’s U.S. ambassador was in Houston conferring with NASA officials. Under Jewish law, mourners normally must bury their dead within 24 hours, then immediately begin observing a mourning ritual.

The remains may be analyzed at the same center that identified the remains of the Challenger astronauts and the Pentagon victims of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack, the Charles C. Carson Center for Mortuary Affairs at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware.

Officials had initially said identification would be done at Dover, but a base spokeswoman, Lieuenant Olivia Nelson, said Sunday: “Things are a little more tentative now. We’re just not sure at this point.”

She said she didn’t know where else the remains might be sent. Dover is the only such military facility in the continental United States.

Among the remains recovered are a charred torso, thigh bone and skull with front teeth, and a charred leg. An empty astronaut’s helmet also could contain some genetic traces.

“DNA analysis certainly can do it if there are any cells left,” said Carrie Whitcomb, director of the National Center for Forensic Science in Orlando, Florida. “If there is enough tissue to pick up, then there are lots of cells.”

Nor does the DNA have to come from soft tissue.

“Identification can be made with hair and bone, too,” said University of Texas physicist Manfred Fink. “Unless the body was very badly burned, there is no reason why there shouldn’t be remains and it should not hinder the work.”

DNA isn’t the only tool available. Despite the extreme nature of the accident, simpler identification methods, such as fingerprints, can be used if the corresponding body parts survived re-entry through the atmosphere.

Dental records and X-rays from astronauts’ medical files can provide matching information, making the discovery of the skull and the leg particularly valuable, they said.

But forensic experts were less certain whether laboratory methods could compensate for remains that were contaminated by the toxic fuel and chemicals used throughout the space shuttle.

“Those would be new contaminants that we haven’t dealt with before,” Whitcomb said.

Despite the hundreds and hundreds of debris sightings swamping law enforcement officials in Texas, recognizable portions of the crew’s capsule had not yet been found.

“If the bodies had been removed from the safeguard of the cabin, they would have totally burned up and very little could be recovered,” Fink said. If the bodies were shielded by portions of the cabin until impact with the ground, he said, identification would be easier.

Disasters such as the World Trade Center attack pushed the science of identification technologies to use new methods, chemicals and analytical software to identify remains that had been burned or pulverized. Researchers said they can work not only with much smaller biological samples, but smaller fragments of the genetic code itself that every human cell contains.

In the 1986 Challenger explosion, an external fuel tank explosion ripped apart the spacecraft 73 seconds after liftoff from the Florida coast. Questions about the demise of the Challenger crew persisted during the investigation that followed.

Challenger’s nose section, with the crew cabin inside, was blown free from the explosion and plummeted 8.7 miles from the sky. NASA learned from flight deck intercom recordings and the apparent use of some emergency oxygen packs that at least some of the astronauts were alive during Challenger’s final plunge. The capsule shattered after hitting the ocean at 207 mph.

Two years after the disaster, NASA officials said forensic analysis did not specifically reveal conclusive evidence about either the cause or time of the astronauts’ death.

On Saturday, Columbia’s crew had no chance of surviving after the shuttle broke up at 207,135 feet above Earth. The spacecraft was exposed to re-entry temperatures of 3,000 degrees while traveling at 12,500 mph, or 18 times the speed of sound.

After the 1996 crash of TWA flight 800 off Long Island, scientists were able to identify all 230 victims from tissue fragments collected from the ocean. An identification rate of 100 percent was almost unheard of at the time.

Information on The Space Shuttle Columbia

ANDERSON, MICHAEL PHILIP

LTCOL US AIR FORCE

- DATE OF BIRTH: 12/25/1959

- DATE OF DEATH: 02/01/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 46 SITE 1180-1

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard