Arctic explorer. Born: Charles County, Maryland, 1866. Died: March 9, 1955, he accompanied United States Navy Commander Robert Peary on an expedition to the North Pole. Henson, Peary, and 4 Eskimos are generally credited to be the first people to reach the pole, on April 6, 1909.

Henson accompanied Peary on each of his eight Arctic voyages and was noted for his technical skills and his ability to communicate with the Eskimo.

The son of a tenant farmer, Henson went to sea at the age of 12. His long association with Peary began in 1887, on a surveying mission to Nicaragua.

His account of the famous final dash to the pole, “A Negro at the North Pole”, was published in 1912. Henson later became a member of the Explorers Club and received honorary degrees from Howard University and Morgan College. Born: August 9, 1866 and died in New York City on March 10, 1955. The man Robert Peary termed indispensable in his final 5-day dash to North Pole.

Press ReportL 27 February 2004

A hero finally gets his due

By Ross Atkin

Reaching the North Pole for the first time in history was success enough for anybody. But for African-American Matthew Henson it was a double victory: a triumph over both a hostile land and the prejudices of a white-dominated society. Today, achievements such as Mr. Henson’s are widely celebrated, especially in February, which is Black History Month.

But things were quite different in 1909. That’s when Henson and Robert Peary reached the Pole. Henson may even have gotten there first. (More on that later.)

The feat brought Peary global recognition, though not immediately, because Frederick Cook claimed to have arrived a year earlier. Eventually, though, Cook’s story was viewed suspiciously, while the Explorers Club, the United States Congress, and others acknowledged Peary as the pioneer.

Henson, though, was cast into the shadows. His recognition was largely confined to the black community. A huge gathering was held for him at the Tuxedo Club in Harlem, attended by educator Booker T. Washington, among others.

White society ignored him. Only in recent times has he received his due, thanks in part to people who championed him after his death.

Honors came later

In 1988, at the urging of Harvard professor Allen Counter, President Ronald Reagan granted a petition to move Henson’s remains to Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C., where many American heroes and soldiers are buried.

In 1996, a Navy ship, the USNS Henson, was named for him. And in 2000, the National Geographic Society gave him its highest honor: the Hubbard Medal for distinction in exploration, discovery, and research.

These are impressive honors, made all the more so by Henson’s uphill climb. He was born in Maryland in 1866, a year after the Civil War ended. By the time he was 11, both his parents had died, and he was entrusted to the care of relatives. At 13, he intrepidly set out on his own, mostly walking 40 miles to Baltimore, where he became a ship’s cabin boy.

That meant peeling potatoes in the galley. During the five years he spent sailing around the world, however, he learned geography, history, and seamanship.

He encountered racial hostility on a subsequent ship job, though, and turned to other work. He became a bellhop, dock worker, messenger, and night watchman.

Then, while working in a Washington, D.C., hat shop, Henson met Peary.

Peary, an engineer and explorer, came in looking for a sun helmet for a trip to Nicaragua. The United States government was sending him to search for a canal route. When the store owner learned that Peary needed a valet, he recommended Henson. The clerk was bright and, at 21, had been around the world already. Peary hired him. In Nicaragua, Henson used the mapmaking skills he’d learned aboard ship to help Peary.

When the trip ended, Peary approached Henson about joining him on a far different adventure: a quest for the North Pole.

As mysterious as the moon

At the time, the North Pole was as mysterious and unattainable as the moon. Little was known about it, other than that it was very cold.

No airplane had flown over the Pole – that wouldn’t happen until 1926. The polar ice field kept ships from sailing there. Some people saw the glow of the northern lights and though Eskimos were burning logs on the “top of the world.” (The aurora borealis, as it’s called, is caused by charged particles from the sun colliding with Earth’s atmosphere.)

By the 1870s, a race had sprung up. Who would be first at the North Pole? It wasn’t a head-to-head race, but a series of expeditions over many years by Americans, Italians, and Norwegians.

Henson had become Peary’s right-hand man, and the two made a number of trips to Greenland and the Arctic beginning in 1891. They covered thousands of miles on dog sleds. After being stymied by blizzards and drifting, cracking ice on six occasions, they mounted a seventh expedition.

‘I cannot make it without him’

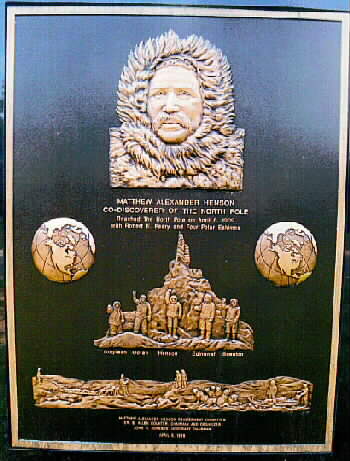

The trek north began after anchoring their ship at Ellesmere Island, at the edge of what is now the Canadian territory of Nunavut. Henson led construction of an igloo base camp, and on March 1, 1909, a relay-style assault on the Pole commenced. It was a major team effort, enlisting about 20 Inuit (also called Eskimos), more than 250 dogs, and large quantities of supplies.

Henson often helped to break the trail during the 475-mile journey and was selected by Peary to join him on the final leg, along with a few Eskimos.

“Henson must go with me,” Peary said. “I cannot make it without him.”

Peary could have chosen one of his white assistants, but he wanted the best man, regardless of race. Henson was a proven leader, skilled at repairing sledges and driving the dog teams. He was also the only American on the expedition who spoke the Inuit language fluently.

The details on what happened next are not clear. According to Harvard University’s Dr. Counter, a Henson historian, Henson was expected to take the lead but stop short of the Pole to let Peary reach it first. Instead, he and two Eskimos inadvertently arrived before realizing their mistake, then waited 45 minutes for Peary to catch up. (Peary, who had frostbitten feet, was being pulled in a sled.)

When Peary realized what had happened, he was so angry that he refused to speak to Henson on the return trip and thereafter maintained a distant relationship more common between blacks and whites of that era.

The expedition’s navigational equipment was not as precise as today’s satellite-based GPS. Today, however, most experts are convinced that Peary and Henson got there before anybody else. (A respected navigation society studied photos Peary’s group took at the Pole. From the angle of the shadows cast, they concluded that the explorers had, indeed, reached the North Pole.

As the leader of the expedition, Peary naturally received major credit. Changing racial attitudes and research, however, have established Henson as a remarkable explorer as well.

A cable-TV movie about Henson’s exploits, “Glory and Honor,” came out in 1997/ A Hollywood version, starring Will Smith, is in the planning stages. A handful of books, including several for young readers, chronicle Henson’s life and polar adventures.

After returning from the Pole, Henson led a quiet existence. He worked for many years in the US Customs Bureau. Before his death in 1955, though, he had the satisfaction of shedding his “unsung hero” status. In 1937 he was elected to the international Explorers Club in New York. In 1945 the US Navy awarded him a medal. And in 1954, President Eisenhower invited him to the White House.

95 years later, you can phone home from the top of the world

Christopher Sweitzer has been to the North Pole twice. The first time hardly counts, though, since he was only 18 months old. As a fifth-grader last April, he returned with his dad, Rick, whose adventure travel business has been offering North Pole trips since 1993.

On his latest journey, a 5-1/2-day trip, he arranged to call his classmates at Highcrest Middle School in Wilmette, Ill., on a satellite phone.

“The connection was pretty good,” says Chris, an outdoorsy 12-year-old who likes to play soccer and baseball when not skiing.

Their trip was far shorter, faster, and more comfortable than the one Robert Peary and Matthew Henson took in 1909. Chris traveled mostly by air.

He and his dad flew to Spitzbergen, an island north of Norway. From there they took a Russian charter flight (in a special plane designed to land on ice) to a base camp on the frozen Arctic Ocean, 60 miles from the Pole. A helicopter took them to within five miles of the Pole. They cross-country skied the rest of the way. It took three hours.

The skiing was a lot tougher than Chris was used to. He often had to get over tall pressure ridges of ice. Another surprise was where they stayed. ‘I never thought about having a base there, with big tents,’ he says.

Tents are used at the oddly named Camp Borneo (the island of Borneo is very hot and humid). The camp is temporary. The Russians who run it set it up for several weeks, usually in April. The camp requires a large, flat stretch of solid ice at least three feet thick, so planes can land.

The tent Chris and his dad stayed in was about 20 feet long, 10 to 15 feet high, and heated. “It was pretty nice,” he says, surely more comfortable than outside, where the temperature was about minus 10 degrees F. (and minus 25 at the Pole).

When Chris called his classmates, they wanted to know what animals he’d seen. On the entire trip, Chris saw only one seal. He didn’t see any polar bears, which was probably just as well, since they have been known to attack humans.

Chris worked so hard skiing the last miles to the Pole that his perspiration froze on his face. Because it’s so cold, rest stops are short and infrequent. On the trips he leads, Rick Sweitzer says the group stops about once an hour just long enough for a little nourishment. ‘Every time you stop,’ Rick says, ‘it takes 15 minutes to warm up when you start again.’

When the Sweitzers’ GPS unit told them they had arrived at the “Pole,” (there’s no actual marker), they found they had company. A group of runners was competing in an extreme marathon, running (well, mostly walking) around a one-kilometer loop. There was a five-hour limit, and only a few contestants finished the race.

Chris watched – from inside the heated helicopter that shuttled him and his dad back to base camp.

From a press report: April 7, 1988: Washington, DC

79 years to the day after he reached the North Pole with Commander Robert E. Peary, Matthew Alexander Henson received a hero’s burial Wednesday in Arlington National Cemetery.

Relatives, friends and admirers, some of them Eskimos who had come from Greenland, laid him to rest beside Peary, hailing the interment not only as the righting of a historical wrong but also as an affirmation that a “new day” in race relations had dawned.

Henson was black and had spent most of his life in historic oblivion. He died in 1955 at the age of 88 and was buried in a simple grave at Woodlawn Cemetery in the New York borough of the Bronx, having spent most of his post-Arctic years obscurely as a clerk at the Customs House in New York City.

Peary died in 1920. He originally hired Henson as a valet and then came to rely upon him as a navigator and Arctic expert. By then Peary was an admiral and ranked among Marco Polo, Magellan and Columbus as a great explorer. Peary is buried under a globe-shaped monument on the crest of an Arlington hill that commands a sweeping view of Washington, DC. Wednesday’s re-interment of Henson, with military honors, concluded a long effort by his admirers and family to win him recognition and burial next to Peary.

A key figure in that effort, S. Allen Counter, a Harvard professor of neurophysiology and a student of the lives of major black figures, said at graveside that Henson had been denied proper recognition in life “because of the racial attitudes of his time.”

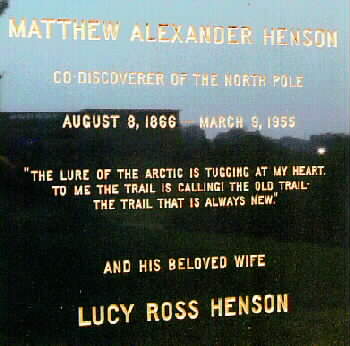

Henson’s wife, Lucy Ross Henson, was re-interred beside him Wednesday. She died in 1968 and was buried at Woodlawn.

Among those at the graveside were 4 Eskimos, descendants of Anaukaq Henson, a son Henson fathered by an Eskimo woman in the Arctic. Qitdlag Henson spoke for the Greenland branch of the family. “We are very proud,” he said in his native tongue, relying upon a translator. “This is a very great day for us.”

Officials who oversaw the re-interment said descendants of Peary had been invited to attend but were unable to.

From a contemporary press report: March 1998:

At the turn of this century, the idea of a man reaching the North Pole was a very big deal. It was so big that some 756 men had died trying to get there.

Then along came Robert E. Peary, a civil engineer with a burning desire to secure a place in the history of exploration by being the first man to stand where there is no east or west.

A key member of Peary’s party was a black man, Matthew Henson. Mainstream American history tended over the years to overlook his role in the success of the expedition that, after several failed attempts, reached the North Pole on April 6, 1909.

In recent years, Henson’s contribution has been put into a clearer perspective, with the man whom Peary hired as a valet in the 1890s getting credit for coming up with key ideas that helped make the polar quest successful. In 1988 his body was moved to Arlington National Cemetery and buried near Peary’s, with a plaque acknowledging him as “co-discoverer of the North Pole.”

This week, TNT offers a two-hour digest of this sprawling story, beginning Sunday at 8 on the cable network. The film, “Glory & Honor,” repeats at 10 and midnight the same evening, then on Tuesday and Saturday, and next Sunday, Monday and Thursday.

The movie attempts to profile the two men and detail the attempt to reach the North Pole, including earlier unsuccessful expeditions.

We are introduced to a driven, self-centered Robert Peary, portrayed by Henry Czerny. Matthew Henson, played by Delroy Lindo, plays a more outwardly directed individual — he’s the one who makes valuable friendships with the native Inuits whom Peary largely ignores.

So much story to tell in so little time, some 92 minutes of narrative. Both lead actors lobbied for fuller portrayals of their characters than that span would permit. Add to that the perils of filming in locations similar to the ones in which the original drama played out — there was at least one heart-stopping mishap on a frozen waterway — and you’ve got quite a handful for executive producer Bruce Gilbert.

In the end, are both historic figures treated fairly? Is one diminished to make room on the screen for the other? Long after the shooting stopped, Lindo still expresses disappointment that the treatment of Henson — so rarely, if ever, treated in dramatic productions — wasn’t more detailed.

Gilbert, meanwhile, points out that choices had to be made in terms of snipping away various details of the story and cutting away some elements entirely. And he sees the story in terms beyond Peary vs. Henson.

“One of the things that attracted me to the story was that it seemed to encapsulate a kind of parable about how to live your life,” said Gilbert.

“By that I mean, Peary represented a way of leading your life that is completely goal-directed. A lot of this is relevant today. Sometimes people think they want to become rich or famous, no matter whether they are a rock star or an investment banker. Often they find if they are successful it feels kind of empty at the end of the day.

“A character like Henson, who starts out kind of undirected, going where the wind blows him, ends up getting the best of what people want from their lives, to live in the moment, to be more process-oriented, to take what life presents them and savor it.”

Henson was no less compelled to get to the Pole than Peary, said Gilbert. But in terms of motive, he took a different path.

“Henson became goal-directed, he wanted to get to the North Pole as much as Peary did,” said Gilbert. “But the added quality he brings to it, that he develops, is he’s able to live every moment along the way and learn what life has to present him.”

So, when the Peary party finds itself base-camped among the Inuit people, Peary is indifferent to them. Henson, meanwhile, makes friends, learns their language and customs and acquires some of the Inuit skills that prove to be keys to a successful expedition.

The diverse motives and styles of the two men make up the show’s title, “Glory & Honor.”

“I’ve always thought,” said Gilbert, “that if Henson had not succeeded in getting to the Pole, he would have been disappointed, for sure, but he would not have been crushed. He would have lived a rich and full life.

“If Peary had not succeeded, he would have been totally defeated. It’s those lessons, I think, that is what the movie is about for me. It is told against the backdrop of reaching the Pole, but it could speak to any of life’s endeavors.”

Meanwhile, one of Lindo’s endeavors was to tell an audience more about Henson than he feels “Glory & Honor” does. From the beginning, he said, and still, he had problems with the treatment given Henson in the script credited to Jeffrey Lewis and Susan Rhinehart.

“When TNT approached me,” said Lindo, “they did not say they were doing the Matthew Henson story. They said they wanted very much to illuminate from his point of view for the audience just what his role had been in the Arctic expeditions.

“We all agreed he’d been historically ignored, and they wanted to change that. Maybe I took that too literally. But the fact is, I took them at their word. That actually is not what the film is. Nominally, maybe, because my character narrates it, but it’s about Henson and Peary.”

Late in the program, in a swift, kiss-less but romantic sequence of scenes, Henson meets Lucy, played by Kim Staunton, courts and marries her.

“I thought it was critical that the two women most important to Matthew Henson’s life, that they be given equal illumination,” said Lindo, who did extensive research on Henson, reading books, visiting locales where Henson had lived and contacting descendants.

The other woman in his life, Lindo said, was an Inuit woman, with whom he fathered a child.

“Both he and Peary had sons by Inuit women,” said Lindo. Henson’s relationship “is not at all in this film. I think that’s something fundamental to who he was as a man.”

Indeed, Peary’s involvement with an Inuit woman is told very pointedly when the explorer’s manor-born wife, played by Bronwen Booth, shows up at a camp and finds him with the heavily pregnant woman.

A sequence involving Henson and an Inuit woman was shot, said Gilbert, but had to be edited out. He noted that Henson had been married before his exploits with Peary, a union that was ending at the point where the movie begins. “If you look closely you’ll see he’s wearing a wedding ring,” said Gilbert.

“There are always aspects of the story you can’t get into,” he said. “You have to make editorial choices as to what’s going to be excised and what’s going to remain. . . . Often in the mechanics of movie-making it comes to taking out a sequence rather than a few seconds here and a few seconds there.”

Time constraints impose a form on movies, Gilbert observed. “Sometimes that’s good — it’s like haiku poetry, there’s a discipline that goes with that.”

The writer-producer has faced the same predicament in other films, he said, including “Coming Home” and “The China Syndrome.” For the controversial “China Syndrome,” centered on a mishap at a nuclear power facility, “you couldn’t believe the research that was piled up concerning nuclear power that did not make it into the movie. You hope to get enough of the essence of the characters to inspire people to look for more information, or for other movie makers to make another treatment of the subject. That’s about the best you can hope for, to give a full presentation being cognizant that in 90 minutes you can’t deal with the character’s entire life.”

Gilbert said he did indeed hear Lindo’s concerns, “and Henry Czerny was just as vocal about his character and trying to make sure that the Peary character from his point of view did not become one-dimensional.

“There was a healthy give and take between actors, producers, writers and directors that is a good thing and a healthy thing because it keeps you on top of the game and gives you the best chance of insuring that the characters stay rich and full-bodied.” The discussions, he said, got heated at times, but never ugly.

The hazards of filming on Baffin Island, however, might well have gotten ugly.

Gilbert and director Kevin Hooks took a cast and crew of more than 150 people to the island off the northeast coast of Canada and shot outdoor scenes near the Arctic Circle.

They went there, Gilbert said, to have a location that offered the variety of landscapes Peary and Henson had encountered, from the mountainous coastline and permanent icecap of Greenland, to vast expanses of frozen ocean. Home base was a now-abandoned air station.

With the forbidding territory came danger. Inuits helped them cope. “I can’t underestimate the effect of being around the Inuit people,” said Gilbert. “This is their environment, they’ve been there far longer than most civilizations on Earth. . . . They’re incredibly warm and open, but they are still this hunter-gatherer society. They savor life and have a respect for nature and animals and you come to respect it too. A small mistake can mean your life.”

Each day, the cast and crew set out in convoys of snowmobiles and sleds to reach shooting locations. “We listened to our guides, who were very knowledgeable,” Gilbert said. “It’s easy to get lost — you go over a rise and can quickly lose perspective.”

On the way back to the base one day, two snowmobiles and the crew on them plunged through the ice. “But the people were fished out, and we saved the snowmobiles too,” recalled Gilbert. “The crew members were cold and scared — but unhurt.”

Contemporary press report:

Thursday, April 7, 1988 – The black co-discoverer of the North Pole got what one supporter called ”long-overdue recognition” as his remains were reinterred with full military honors Wednesday at Arlington National Cemetery.

The black explorer, Matthew Alexander Henson, was the first to reach the North Pole and planted the American flag there during a trek with Admiral Robert E. Peary and four Eskimos in 1909.

Peary was buried at Arlington in 1920 and a monument to him was erected at his grave. But when Henson died in 1955, his body ended up in a shared grave at Woodlawn Cemetery in New York because his wife was unable to afford a separate grave site.

”He was denied proper recognition because of the racial attitudes of his time,” said S. Allen Counter, a Harvard professor who successfully petitioned President Ronald Reagan to allow Henson’s reinterment at Arlington.

Counter previously brought together Henson’s and Peary’s part-Eskimo offspring. He told about 100 relatives and admirers at the hilltop burial site that the reinterment of Henson and his wife, Lucy Ross Henson, was ‘long-overdue recognition for our hero . . . (that would) right a tragic wrong.”

Henson’s remains now rest alongside Peary’s, with the remains of their wives on either side.

Descendants of Matthew and Lucy Henson were joined at the ceremony by Henson’s part-Eskimo descendants who were fathered when he was in the Arctic.

”Now, finally, Matthew Henson and Robert Peary can talk about old days out there,” a grandson, Qitdlaq Henson of Qaanaaq, Greenland, said through a translator at a news conference after the ceremony.

Counter said the cost of the reinterments – including exhuming the Hensons from the cemetery in New York, the two bronze caskets, the monument, bringing Henson’s offspring from Greenland and the rest of the arrangements – ran into the thousands. But he refused to be more specific or say exactly who paid for what.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard