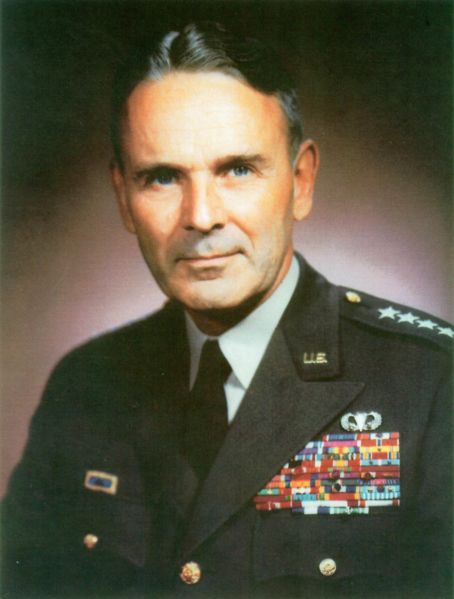

General Maxwell Davenport Taylor (August 26, 1901 – April 19, 1987) was an American soldier and diplomat of the mid-20th century.

Taylor was born in Keytesville, Missouri and graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1922.

World War II

Taylor’s rise to the highest echelons of U.S. government began under the tutelage of General Matthew B. Ridgway in the US Army’s 82nd Airborne Division when Ridgway commanded the division in the early part of World War II. In 1943, his diplomatic and language skills resulted in his secret mission to Rome to coordinate an 82nd air drop with Italian forces. He met with the new Italian Prime Minister, Marshal Pietro Badoglio. The air drop near Rome to capture the city was called off at the last minute, when Taylor realized that it was too late. German forces were already moving in to cover the intended drop zones. Transport planes were already in the air when Taylor’s message cancelled the drop, preventing the suicide mission. These efforts behind enemy lines got Taylor noticed at the highest levels of the Allied command.

After the campaigns in the Mediterranean, Taylor was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division, which was training in England. After the 101st’s founder and commander Major General Bill Lee suffered a heart attack, Taylor was given command of the division.

Taylor jumped into Normandy on June 5, 1944 with his men. He was the first Allied general to land in France on D-Day. He held command of the 101st Airborne Division for the rest of the war, but missed out leading the division during its most famous conflict, the Battle of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge, because he was attending a staff conference in the United States. General Anthony McAuliffe was there and assumed command. Some of the paratroopers resented Taylor for this later.

[ From 1945 to 1949 he was superintendent of West Point, afterwards he was the commander of allied troops in Berlin from 1949 to 1951.

In 1953, he was sent to the Korean War. From 1955 to 1959, he was the Army Chief of Staff, succeeding his former mentor, Matthew B. Ridgway. During his tenure as Army Chief of Staff, Taylor attempted to guide the service into the age of nuclear weapons by restructuring the infantry division. Observers such as Colonel David Hackworth have written the effort gutted the role of US Army company and field grade officers, rendering it unable to adapt to the dynamics of combat in Vietnam.

During 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered General Taylor to deploy 1,000 troops from the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock, Arkansas to enforce Federal court orders to desegregate Central High School during the Little Rock Crisis.

As Army Chief of Staff, Taylor was an outspoken critic of the Eisenhower Administration’s “New Look” defense policy, which he viewed as dangerously over-reliant on nuclear arms and neglectful of conventional forces; he also criticized the inadequacies of the Joint Chiefs of Staff system. Frustrated with the administration’s failure to heed his arguments, General Taylor retired from active service in July of 1959. He campaigned publicly against the “New Look,” culminating in the publication in January 1960 of a highly critical book entitled “The Uncertain Trumpet.”

As the 1960 presidential campaign unfolded, Democratic nominee John Kennedy criticized Eisenhower’s defense policy and championed a muscular “flexible response” policy intentionally aligned with Taylor’s views as described in “The Uncertain Trumpet.” After the April 1961 failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy, who felt the Joint Chiefs of Staff had failed to provide him with satisfactory military advice, appointed Taylor to head a task force to investigate the failure of the invasion.

Both President Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, had immense regard for Taylor, whom they saw as a man of unquestionable integrity, sincerity, intelligence and diplomacy. The Cuba Study Group met for six weeks from April to May 1961 to perform an ‘autopsy’ on the disastrous events surrounding the Bay of Pigs invasion. In the course of their work together, Taylor developed a deep regard and a personal affection for Robert F. Kennedy, a friendship which was wholly mutual and which remained firm until Kennedy’s assassination in 1968.

Taylor spoke of Robert Kennedy glowingly, “He is always on the lookout for a ‘snow job’, impatient with evasion and imprecision, and relentless in his determination to get at the truth.” Robert Kennedy named one of his sons Matthew Maxwell Taylor Kennedy (better known as an adult as “Max”).

Shortly after the investigation concluded, the Kennedys’ warm feelings for Taylor and the president’s lack of confidence in the Joint Chiefs of Staff led John Kennedy to recall Taylor to active duty and install him in the newly-created post of “Military Representative to the President.” His close personal relationship with the President and White House access effectively made Taylor the president’s primary military advisor, cutting out the Joint Chiefs. On 1 October 1962, Kennedy ended this uncomfortable arrangement by appointing Taylor as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a position in which he served until 1964.

Taylor was of crucial importance during the first weeks and months of the Vietnam War. Whereas initially President Kennedy had told Taylor that “the independence of South Vietnam rests with the people and government of that country,” Taylor was soon to recommend that 8,000 American combat troops be sent to the region at once. After making his report to the Cabinet and the Chiefs of Staff, Taylor was to reflect on the decision to send troops to South Vietnam that, “I don’t recall anyone who was strongly against, except one man, and that was the President. The President just didn’t want to be convinced that this was the right thing to do…. It was really the President’s personal conviction that U.S. ground troops shouldn’t go in.”(Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy: His Life and Times)

Taylor received fierce criticism in Major (now Colonel) H.R. McMaster’s book “Dereliction of Duty”. Specifically, General Taylor was accused of intentionally misrepresenting the views of the Joint Chiefs to Secretary of Defense McNamara, and cutting the Joint Chiefs out of the decision making process. Whereas the Chiefs felt that it was their duty to offer unqualified assessments and recommendations on military matters, Gen. Taylor was of the firm belief that the Chairman should not only support the President’s decisions, but also be a true believer in them. This discrepancy manifested itself during the early planning phases of the war, while it was still being decided what the nature of American involvement should be. McNamara and the civilians of the Office of the Secretary of Defense were firmly behind the idea of graduated pressure, that is, to escalate pressure slowly against the N. Vietnam, in order to demonstrate US resolve. The Joint Chiefs, however, strenuously disagreed with this, and believed that if the US got involved further in Vietnam, it should be with the clear intention of winning, and through the use of overwhelming force. Using a variety of political maneuvering, including liberal use of outright deception, McMaster contends that Gen. Taylor succeeded in keeping the Joint Chief’s opinions away from the President, and helped set the stage for McNamara to begin to dominate systematically the US decision making process on Vietnam.

He again retired and became Ambassador to South Vietnam from 1964 to 1965, succeeding Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. He was Special Consultant to the President and Chairman of the Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (1965–1969) and President of the Institute for Defense Analyses (1966–1969).

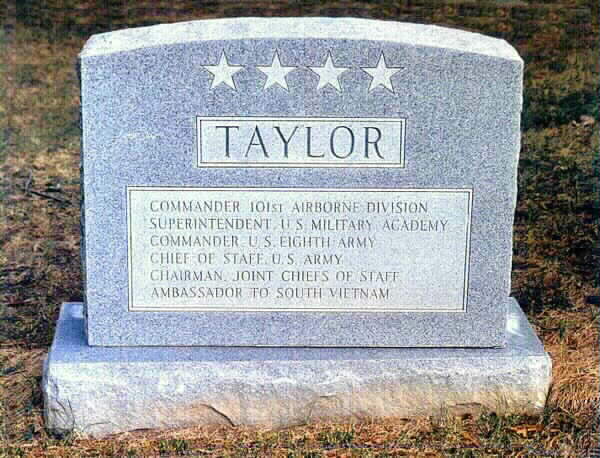

General Taylor died in Washington, D.C. on 19 April 1987 of Lou Gehrig’s Disease. He was interred at Arlington National Cemetery

Awards:

- Distinguished Service Cross

- Distinguished Service Medal

- Silver Star

- Legion of Merit

- Bronze Star

- Purple Heart

Maxwell Davenport Taylor was born in Keytesville, Missouri, on 26 August 1901.

He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1922 and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant of Engineers in June 1922, and then attended his branch course. He served in Hawaii with the 3d Engineers, 1923–1926, and married Lydia Gardner Happer in 1925.

He transferred to the Field Artillery and served with the 10th Field Artillery, 1926–1927. He was promoted to First Lieutenant in February 1927. He studied French in Paris and was instructor in French and later Spanish at West Point, 1927–1932; he graduated from the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 1933, and from the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1935.

He was promoted to Captain in August 1935 and was a student of Japanese at the American embassy in Tokyo from 1935 to 1939, with detached military attaché duty at Peking, China, in 1937. He graduated from the Army War College, 1940, and was promoted to permanent Major in July 1940. He then served in the War Plans Division and on a Hemisphere defense mission to Latin American countries in 1940. He then commanded the 12th Field Artillery Battalion, 1940–1941; and served in the Office of the Secretary of the General Staff, 1941–1942.

He received temporary promotions to Lieutenant colonel in December 1941, to Colonel in February 1942, and Brigadier General in December 1942. He was then Chief of Staff of the 82d Airborne Division in 1942, then its artillery commander in operations in Sicily and Italy in 1942 to 1944. He received temporary promotion to Major General in May 1944 and commanded the 101st Airborne Division in the Normandy invasion and the Western European campaigns, 1944–1945; He was promoted to permanent Lieutenant Colonel in June 1945, and Brigadier General in January 1948.

He was chief of staff of the European Command in 1949, and commander of the United States forces in Berlin, 1949–1951; He was promoted to temporary Lieutenant General and permanent Major General in August 1951; He was then Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations, G–3, and Deputy Chief of Staff for operations and administration, 1951–1953; He was promoted to temporary General in June 1953. The then was commander of the Eighth Army in the final operations of the Korean War in 1953 and then initiated the Korean armed forces assistance program, in 1953 and 1954. He commanded United States Forces, Far East, and the Eighth Army 1954–1955, and was Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, 1955; He was Chief of Staff of the United States Army, 30 June 1955–30 June 1959 and opposed dependence upon a massive retaliation doctrine, pushing for an increase in conventional forces to ensure a capability of flexible response, guided the transition to a “pentomic” concept, and directed Army participation in sensitive operations at Little Rock, Lebanon, Taiwan, and Berlin.

General Taylor retired from active service in July 1959 and was recalled as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1962–1964. He again retired and became Ambassador to South Vietnam, 1964–1965; he was Special Consultant to the President and Chairman of the Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, 1965–1969; was President of the Institute of Defense Analysis, 1966–1969.

General Taylor died in Washington, D.C., on 19 April 1987.

To fellow cadets at West Point, where he graduated in 1922, and to contemporaries during World War II, he was an “intellectual,” a scholar who had an affinity for foreign languages. That may have been one reason he was called upon in 1943 for one of the war’s most unusual missions, a daring trip by patrol boat to the Italian coast near Rome, then by Red Cross ambulance into the capital for what turned out to be a futile attempt to gain Italian complicity in a landing of U.S. airborne divisions to occupy Rome coincident with the Italian surrender.

One of the United States Army’s airborne enthusiasts, he fought in Sicily and Italy as the Artillery Commander of the 82nd Airborne Division. He commanded the 101st Airborne Division in airborne assaults in France on D-Day (June 6, 1944), in Operation Market in the Netherlands and in ground operations during the Battle of the Bulge and the drive through Germany.

His post-World War II career involved many major assignments: Superintendent of West Point; Commander of the Eighth Army in Korea; Army Chief of Staff; Special Military Advisor to President John F. Kennedy and President Lyndon B. Johnson; Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; and Ambassador to Vietnam.

He died on April 19, 1987 at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. In announcing his death, the Pentagon said that he had been admitted to the hospital in mid-January and that he died of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, a degenerative disease of the nerve cells that is better known as Lou Gerhig’s Disease. He was buried in Section 7-A of Arlington National Cemetery, just a short distance from the Memorial Amphitheater and the Tomb of the Unknowns.

His wife, Lydia Happer Taylor, died on April 22, 1997 at the age of 95, of cardiac arrest at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C. She accompanied her husband to assignments in Germany, Vietnam and Japan. She was the co-founder of the Army Distaff Foundation, which later became Knowllwood, a military retirement facility in Northwest Washington.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard