Born at Albany, New York, August 17, 1896, he attended the University of Washington for one year and the Massachuetts Institute of Technology for two years before entering West Point from which he graduated in 1918.

He was commissioned in the Engineers and took courses at the Engineer’s School, Camp Humphreys (now Fort Belvoir), Virginia, 1918-20 and 1921, with time out for brief service in France during World War I. His assignments over the next decade included San Francisco, Hawaii, Delaware and Nicaragua.

In 1931 he was attached to the Office of the Chief of Engineers in Washington and was promoted to Captain in October 1934. In 1936 he graduated from the Command and General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and from the Army War College in 1939, after which he was assigned to the General Staff in Washington.

He was promoted to Major and Temporary Colonel in July and November 1940 and assigned first to the Office of the Quartermaster General and then to the Office of the Chief of Engineers, where his responsibility for the oversight of army construction projects included supervision of the building of the Pentagon building.

In September 1942 he was placed in charge of the Manhattan Engineer Project, established a month earlier, with the rank of Temporary Brigadier General. The Manhattan Engineer Project was the cover name for the atomic bomb project and, under his direction, the basic atomic bomb research was carried out, mainly at Columbia University and the University of Chicago. Project plants were established at the Clinton Laboratory at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the Hanford Engineer Works near Pasco, Washington, and the secluded Los Alamos installation in New Mexico. Much of the $2-Billion expended by him came through blind appropriations. The purchase and transport of materials, the hiring of labor (the force reached 125,000 at its zenith) and construction of plants had all to be carried out with upmost care and secrecy. Not the least of his tasks was to deal successfully with large numbers of civilian scientists and technicians employed in the project. The work culminated in the first successful explosion of a nuclear-fission bomb at Alamogordo, New Mexico, July 16, 1945. In the three years since the project was organized, no major obstacles and no serious breach of security had occured.

He had been promoted to temporary Major General in December 1944, and he continued to head the atomic establishment created during wartime until January 1947. He was then named the Chief of the Army’s Special Weapons Project. Promoted to Lieutenant General (temporary) in January 1948, he retired a month later. From that time until 1961 he worked as Vice President of Sperry Rand Corporation.

He died of heart disease on July 13, 1970 and was buried in Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Grace Hulbert Wilson Groves, whom he married on February 10, 1922, is buried with him.

June 21, 2002, 5:40PM

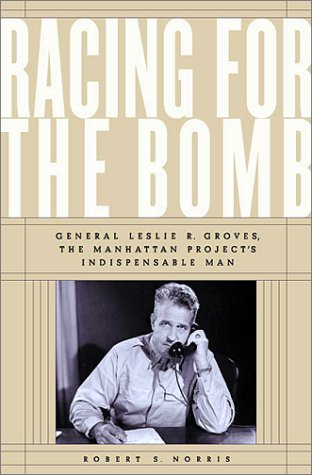

RACING FOR THE BOMB

General Leslie R. Groves, The Manhattan Project’s Indispensable Man

By Robert S. Norris

Steerforth Press

Copyright © 2002 Robert S. Norris.

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1-58642-039-9

Preface:

Nearly sixty years after the end of World War II, the public’s fascination with the Manhattan Project shows no sign of diminishing. The story of developing, testing, and dropping the atomic bomb is an exciting one, filled with the elements of great novels and high drama. The stakes at the time were huge, the political and moral issues profound, the legacy in the decades that followed lasting.

The most glaring omission in the vast literature about the Manhattan Project is the personal history of the key person who made it a success, General Leslie R. Groves. Remarkably, there is no scholarly biography of him, of how he helped shape one of the great events of the twentieth century. Most histories mention Groves, of course, usually having him appear on the scene in September 1942 to take charge. Sometimes passing reference is made to him having overseen the building of the Pentagon, or that he went to West Point and was an engineer, but not much else. His character remains indistinct and out of focus. While he is described as the chief administrator, he is not shown going about his task or depicted as the indispensable figure, integral to the success of the project. In overlooking Groves’s role we lose valuable perspectives on many interesting debates that continue to surround the bomb. To place Groves back at the center of events, where he was and where he belongs, offers new insights into these important issues.

The purpose of this book is to provide a fuller picture of the life and career of Leslie Richard Groves, and his role in the beginnings of the atomic age. What did he do the first forty-six years of his life to prepare him for his most important assignment? Why did the leadership of the army pick him to manage the Manhattan Project, and how did he administer it? What influence did he have on the use of the bomb on Japan at the end of the war? Would the bomb have been ready in time for use without him? What did he do after the war?

Of equal import, and equally neglected, is the question of Groves’s influence in shaping what is sometimes called the national security state. The phrase attempts to define the new governmental departments and agencies that emerged in the aftermath of World War II and evolved throughout the Cold War, and the procedures and practices by which they operated. These features include the widespread concern for security and secrecy, compartmentalization as an organizing scheme, “black” budgets, the reliance on intelligence and counterintelligence, and the interlocking relationship of government, industry, science, and the military. All of them first emerge during the Manhattan Project.

At the center of the Cold War – the thing that made it different from all that came before – was the bomb. Though Groves was not alone in recognizing this, he did understand, long before it was used, how important this weapon was going to be in the new world to come.

I will argue that Groves was the indispensable person in the building of the atomic bomb and was the critical person in determining how, when, and where it was used on Japan. Without Groves’s vision, drive, and administrative ability, it is highly unlikely that the atomic bomb would have been completed when it was. The Manhattan Project did not just happen. It was put together and run in a certain way: Groves’s way. He is a classic case of an individual making a difference. Being in the right place at the right time is the secret of winning a place in history; rarely does a person arrive there by accident.

Though his perspective was always that of an engineer and an administrator, Groves’s grasp of the pertinent scientific principles was more than enough to get the job done. He displayed a remarkable ability to choose among technical alternatives when it was hard to know which path would deliver results, and he did so quickly. He made many crucial decisions that, had they been the wrong ones, would have resulted in failure or delay. His judgment of whom to choose as his subordinates and whom to rely upon for counsel and advice was uncanny. To get such things right once or twice might be considered a matter of luck. To do so over and over speaks to a person having informed judgment and keen instincts. Of all the participants in the Manhattan Project, he and he alone was indispensable.

The way Groves has been depicted in the literature about the Manhattan Project is mostly a collage of inaccuracies, caricatures, or superficialities. Supposedly authoritative sources do not get even the most basic facts of his life correct. An example is the entry in Oxford University Press’s American National Biography. The author has Groves accompanying his father to Cuba and the Philippines, serving a three-month tour of occupation duty in France with the American Expeditionary Force immediately after World War I, having two daughters, winning the Nicaraguan Medal of Merit for his work there on a canal, spending six million dollars a month constructing military facilities on the eve of the war, and assuming control of the Manhattan Project (med) on September 7, 1942. We also learn that by the spring of 1945 there was enough plutonium to create several weapons, that “a 400-pound device” nicknamed Little Boy demolished Hiroshima on August 6, and that four days later Nagasaki was bombed. Just about every “fact” cited here is wrong.

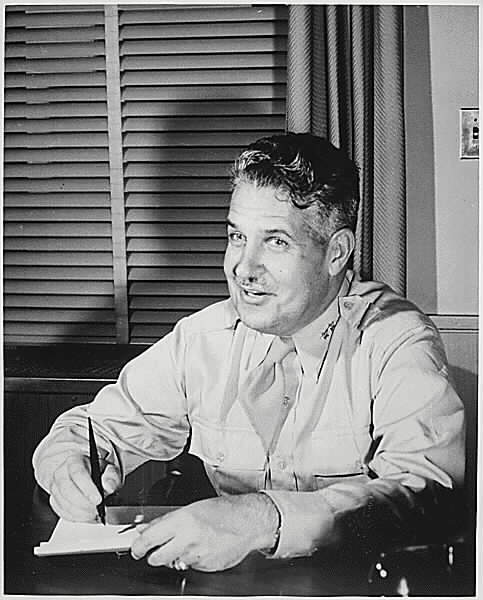

In fact Groves was a larger-than-life figure, a person of iron will and imposing personality who knew how to get things done. He was ambitious, proud, and resolute. From the moment he was appointed to head the Manhattan Project, he was determined that the atomic bomb should be the instrument to end the war. For that to happen required enormous effort constructing and operating industrial plants of unprecedented size and function, with no moment lost.

He was brusque, sometimes to the point of rudeness, and cared little what others thought of him. He expected immediate, unquestioning compliance with his orders, and had little patience with abstract ideas, which might distract from the immediate job at hand. He reacted firmly and defensively to those he judged as threats to the attainment of his goals. His detractors often pointed to his corpulence as a sign of his unsuitability for the post he occupied. Exactly why this was the case is never explained, but it reinforced their negative image of him as arbitrary and ignorant. When he was overweight, which was most of the time, he did not look like what we expect a general to look like, but it had no effect on his ability.

The book is divided into seven parts and is largely chronological. The first three parts – ten chapters in all – cover Groves’s life and career to the point of being chosen to head the Manhattan Project. Groves’s roots are traced back to the mid-seventeenth century. The general’s deep-seated patriotism derives in part from being an eighth-generation American, with special pride reserved for a few military forebears. Son of an army chaplain, Groves grew up on forts and posts all across America amid the military culture and traditions of the early twentieth century. This exposure, plus a highly competitive family situation, set him apart as a self-sufficient and driven young man. For reasons that we will see, his upbringing fostered self-reliance and independent judgment. From an early age he was iron willed and insistent on doing things his way. Self-assured and confident of what he wanted, he had decided by the time he was sixteen that the army would be his calling, and that it was essential to get into West Point. During his years there – abbreviated by the pressure of World War I – Groves earned an excellent record, graduating fourth in his class and choosing the elite Corps of Engineers as his branch.

Over the next twenty-three years, to mid-1942, Groves gained extensive experience participating in, and at times overseeing, a variety of construction and engineering projects. Along the way he met and worked with scores of army officers, corporation executives, architects, engineers, and contractors, many of whom he would later recruit to help him build the bomb. It is crucially important to examine who these people are and the relationships that Groves had with them. In this period we also see Groves’s personality shaped in fundamental ways by the special mores, traditions, and culture of the interwar army and Corps of Engineers.

Just before entering Engineer School in 1919, Groves and his classmates went to Europe for a short summer study tour of the battlefields of France and Germany, his developing engineer’s mind soaking in everything he saw. We also see him express his contempt and distrust of European culture and his belief in the superiority of everything American.

Groves married his longtime sweetheart and started a family. His career advanced steadily as years of hard work increasingly drew the attention of his superiors. A four-year tour in the chief’s office in Washington put him in a small circle of engineers that would have an enormous influence on his career and perspective. Foremost among them was Col. Ernest Graves, the person from whom he probably learned the most. Clearly marked for advancement by senior officers, he was then sent to the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and later the War College, completing the schooling expected of those who hold high positions in the army.

The busy three years prior to being chosen to head the Manhattan Project started with an assignment to the General Staff, then to positions with army construction during the mobilization period for World War II. By the spring and summer of 1942 Groves was basically in charge of all army construction in the United States, overseeing hundreds of projects and expending huge sums of money. One of these many projects was to build the Pentagon.

The core of Groves’s life was the extraordinary experience, beginning in the fall of 1942, of running the Manhattan Project. After the war, one of his aides provided an acute characterization of the different roles that he performed simultaneously: “General Groves planned the project, ran his own construction, his own science, his own army, his own State Department and his own Treasury Department.”

New insights about the Manhattan Project emerge by sharply focusing on Groves’s expanding responsibilities from 1942 to 1945. At the outset he was engineer and builder, charged with constructing the plants and factories that would make the atomic fuels – highly enriched uranium and plutonium. As the project accelerated, Groves came to oversee a vast security, intelligence, and counterintelligence operation with domestic and foreign branches. Through his final-decision-making power he was ultimately in charge of all scientific research and weapon design and kept close watch on the laboratory at Los Alamos. He was involved in many key high-level domestic policy issues, and in several international ones as well. By 1945, in addition to all else, he effectively became the operational commander of the bomber unit he established to drop the bomb, and was intimately involved in the planning, targeting, and timing of the missions. One is struck, in discovering all of his many activities, by just how much power Groves accrued. As a West Point classmate and friend later observed, “Groves was given as much power in that position as any officer ever has had.” A remarkable statement.

Basically Groves made nearly all of the significant decisions having to do with the bomb, from choosing the three key sites – Oak Ridge, Los Alamos, and Hanford – to selecting the large corporations to build and operate the atomic factories. He chose the key military officers who were his subordinates as well as such important figures as Robert Oppenheimer and William S. Parsons, the weaponeer aboard the Enola Gay in charge of dropping the bomb on Hiroshima. We are fortunate to have an extensive record of his daily activities while he ran the Manhattan Project, kept by his trusted secretary, Jean O’Leary. Groves’s detailed appointment book notes thousands of telephone calls, the visitors to his office, the appointments he had outside the office, and even some of what was discussed in calls he made to Washington when he was traveling. It is a valuable contribution toward our understanding of how Groves managed the project day in and day out. The cast of characters is enormous. Familiarity with who they were and what roles they played in building the bomb is essential to understanding Groves’s centrality.

Just as important as building the bomb are the complex and controversial questions surrounding its preparation, its use against Japan, and the immediate aftermath. Groves knew from the outset that the factor setting the pace for the entire project was the availability of the atomic fuels. When there was enough highly enriched uranium and/or plutonium, the use of a bomb would soon follow. In an extraordinary coincidence, there were sufficient amounts of each fuel ready at approximately the same time, and within a matter of days after the material was incorporated into the two types of bombs, they were used to destroy two Japanese cities.

This was essentially Groves’s doing, through his role in the Target and Interim Committees and his supremacy in controlling the test at Trinity and the combat missions to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In most of the vast literature about the decision to use the bomb and the bomb’s role in ending the war, Groves has been slighted or ignored altogether. In fact, given his commanding position at the center of all the activities having to do with the bomb, he actually was the most influential person of all. It was primarily due to him that usable bombs were ready when they were and were employed immediately afterward. Groves alone knew all the details of the bomb and as a result controlled its testing, production, transport to the Pacific, and delivery on Japan. This of course was his job, and he performed it with a fervor and determination that few, if any, could have matched. He was the right man at the right place for the job. His superiors, civilian and military, were in perfect agreement that the bomb should be used when ready. As project head Groves had created a structure of such magnitude and momentum that it was, by mid-1945, unstoppable. By the summer of 1945 a decision not to drop the bomb would have been almost impossible. The “decision” to use the bomb was inherent in the decision made years before, to build it.

Groves’s personal feelings about the bomb were not complicated: He never had any moral doubts, at the time or afterward, about using it. From the outset he believed that the bomb could be decisive in ending the war and saving American lives. As it turned out, with regard to the Pacific war it did both.

Groves never lacked ambition; nor was he modest about his accomplishments. From the outset of war he hoped that his efforts might contribute to winning it. In 1942 he was denied the opportunity to go to the theaters of war overseas. His actions make it clear that after a few moments of disappointment, he decided that building the bomb would be his achievement. Knowing it might end the war was one source of Groves’s extraordinary determination and energy.

But Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not the end of Groves’s job. When the bomb was no longer a secret, a host of new questions quickly emerged. Groves was instrumental in the preparation of much of the initial information released to the public about where and how the bomb was produced and the interesting personalities that were responsible. He did this through overseeing the writing of the president’s and secretary of war’s statements, press releases, and the Smyth Report, as well as allowing New York Times science reporter William Laurence exclusive access to the Manhattan Project.

Groves’s final battles centered on the transfer of the Manhattan Project to the civilian Atomic Energy Commission, his involvement in the questions of international control of atomic energy, and his position as chief of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project. Literally overnight Groves’s situation changed dramatically, and Groves had trouble adjusting to the new rules of the postwar Pentagon and Washington politics. His often high-handed style and treatment of people during the war eventually caught up with him as several of the powerful enemies he made along the way had their revenge. In the end he was forced into early retirement.

After he left the army in 1948, he worked for Remington Rand (later Sperry Rand) and moved to Darien, Connecticut. He remained a public figure throughout the 1950s, speaking and writing on issues of the day, but from the sidelines. Much time was spent overseeing how his major accomplishment, the Manhattan Project, was being dealt with in histories, biographies, newspaper and magazine articles, films, and television. He wrote his own account, Now It Can Be Told, which was published in 1962. He kept up an extensive correspondence, served as president of West Point’s alumni organization, the Association of Graduates, and took charge of building a retirement home for army widows. He retired from Sperry in 1961, and he and his wife moved back to Washington three years later. In his final years he led a quiet life, occasionally visiting his son and daughter, and enjoyed being a grandfather to his seven grandchildren.

General Groves left a deep imprint on the nuclear age that followed, one not always appreciated. Along with his broad influences on domestic institutions and international relations, Groves’s hand is more clearly seen in the direct descendants of the Manhattan Engineer District itself. In many respects the practices and culture of the Manhattan Project carried over to the Atomic Energy Commission and its successors, and have lasted to this day. Hanford, Oak Ridge, and the many other facilities in the nuclear complex always have been run on the government owned-contractor operated (goco) basis that Groves first implemented. The university-laboratory relationship is intact, with the University of California running Los Alamos and Livermore. The AEC from its inception was largely a nonaccountable bureaucracy shielded from the public and most of Congress by layers of classification and secrecy, and the invocation of “national security.” Arguments to build more and more bombs always took precedence over environmental, health, and safety issues, resulting in a troubling and costly legacy.

The Manhattan Project is also periodically held up as a model to emulate whenever the nation decides to undertake a large endeavor. It is worth asking what lessons from the Manhattan Project might be transferable to other large projects, and what was unique to the time.

Counterfactual arguments are popular in the literature about the bomb, and are sometimes useful exercises. One question worth pondering is what would have happened in the decades following World War II if the bomb had never been invented. Would there have been a major conventional war between the Soviet Union and the West? Probably so. As with all counterfactual arguments, however, we will never know. What we do know is that there was not a major war, and the bomb surely had something to do with this. The second half of the twentieth century remained a dangerous time, and the arms race threatened at times to spin out of control, but a major war between the superpowers was averted.

Two basic ways of attempting to live in a world with nuclear weapons confront us today, just as they did Groves. His way – and it is still the way of most – was the unilateral one. In a dangerous world a nation must depend upon itself, just as an individual has to. Trust and cooperation should not be relied upon given figures such as Hitler, Stalin, or their descendants.

The contrary path has its advocates, too. Two of the wiser men of the twentieth century saw early on that the bomb might bring a new type of order into the world. In 1943 Niels Bohr asked Robert Oppenheimer, “Is it big enough?” By this he meant, Was the bomb of such destructive power that it would make war impossible? Einstein’s words convey the same thought: “It may intimidate the human race into bringing order into its international affairs, which, without the pressure of fear, it would not do.” Order we do not have. But peace, of a kind, we do – or at least the absence of major wars between great powers following Hiroshima.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard