John Wyer Summerhayes of New York

Appointed from New York, Private, Corporal, Sergeant and Sergeant Major, 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 9 September 1861 to 14 March 1863

Appointed Second Lieutenant, 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 14 March 1863

Promoted to First Lieutenant, 8 September 1863

Promoted to Captain, 10 October 1863

Breveted Major of Volunteers, 9 April 1865 for meritorious service in the campaign terminating with the surrender of the insurgent army under General R. E. Lee

Honorably mustered out of the volunteer service, 6 June 1865

Appointed Second Lieutenant, 33rd United States Infantry, 22 January 1867

Transferred to the 8th United States Infantry, 3 May 1869

Promoted to First Lieutenant, 15 December 1874

Regimental Adjutant, 1 January 10 19 May 1886

Regimental Quartermaster, 20 May 1886 to 9 March 1889

Captain, Assistant Quartermaster general, 25 February 1889

Major, Chief Quartermaster of Volunteers, 12 May 1898

Honorably discharged from the volunteer service, 2 December 1898

Major, Quartermaster, 11 November 1898

Retired 6 January 1900

Breveted First Lieutenant, United States Volunteers, 2 March 1867., for gallant and meritorious service in the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, Virginia, and Captain, United States Volunteers, 2 March 1867, for gallant and meritorious service in the battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia

John W. Summerhayes, survived the war and made a career of the United States S Army. He died in 1911 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

John Wyer Summerhayes Died on 29 September 1918

His wife, Martha Summerhayes, died on 11 May 1926

Both are buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Section 1, Grave 153C

Among the wounded, Brigadier General Pettigrew of SC & Lieutenant Colonel Bull of the 35th Georgians. Pettigrew had given up all his side arms to some of his people before they ran away, in anticipation of being taken prisoner, & had only his watch, which of course I returned to him. Pettigrew will get well. Bull had his side arms, of which I allowed Corporal Summerhayes, his captor, to keep his pistol, an ordinary affair, while I kept his sword, an ordinary U.S. infantry sword, which I intended to send as a present to you, but the Colonel, knowing [p.129] his family’s address, wants me to send it to them, & as the poor fellow is dead, of course I can’t hesitate to do any thing which would comfort his family. His scabbard, however, I found very convenient, as mine got broken in the battle and I threw it away. I am going to send you, instead, a short rifle which I took from a Hampton’s] Legion fellow, who were all around with them & the sword bayonet. The rest of the rifles we of course turned over to the col., as in duty bound, except one revolving Colt’s rifle, 5 barrels, worth $60 or $70 apiece …which one of my men took from a dying officer, & which I let him keep as a reward of valor.”

–Robert Garth Scott, ed., Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Major Henry Livermore Abbott (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991) pp. 128-129.

20th Massachusetts: Corporal John W. Summerhayes’ account:

“Lieutenant Abbott ordered me into the woods, with a file of men, to bring out all the wounded, and rebels, that could be found. As I started, seven came out, belonging to the Hampton Legion, S.C., the finest brigade in the rebel service. After coming in with them, I advanced into the woods, and hearing a groaning, walked up and there found Lieutenant Colonel Bull of the 34th Georgia [sic]. I took his sword and revolver, and sent him in. After taking several more, I fell in with one, whom I knew, although his side arms were gone, was of some high rank, and so he proved to be. Although he would not give me any answers, the Colonel was more fortunate, for he found out that it was Brigadier General Pettigrew, of the State of South Carolina.”

–Richard F. Miller and Robert F. Mooney, The Civil War: The Nantucket Experience (Nantucket: Wesco Publishing, 1994) pp. 187.

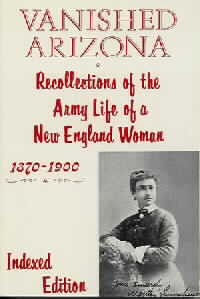

VANISHED ARIZONA is a look at the old West by someone who lived through the hardships and privations of Army life on the frontier. As a young bride, Martha Summerhayes joined her Second Lieutenant husband, Jack Summerhayes, at Fort Russell in Wyoming Territory in 1874. She had grown up in the civilized East at Nantucket, and nothing there prepared her for life on the frontier. With no doctor and no woman on base to help her, Mattie had her baby, and barely survived.

Before she fully recovered from the birth of her son, they were transferred to Camp Ehrenburg in Arizona, a place as harsh and desolate as any place could be. They traveled overland by Army ambulance, not the most comfortable of conveyances. They were in constant danger from Indian attacks, and ran short of food while they followed their guide to their new home. In Arizona, the bitter cold winters of the north were replaced by the scorching heat of the desert in summer. The climate was good for sick children, but it took its toll on Mattie.

You will laugh with her, though, as she sees the reaction of the officer’s wives to their “butler,” a Maricopa Indian named Charlie, who wore a G-string and nothing else. You will smile as she bemoans the lack of servants, something most of us know how to do without, and you will sympathize as she recounts her desire to shuck the dresses of the “civilized” East for the cooler and more comfortable dress of the Mexican women. Truly, Martha Summerhayes is a living voice from the past.

Vanished Arizona: Recollections of the Army Life by a New England Woman

CHAPTER XXXIII

DAVID’S ISLAND

At Davids’ Island the four happiest years of my army glided swiftly away.

There was a small steam tug which made regular and short trips over to New Rochelle and we enjoyed our intercourse with the artists and players who lived there.

Zogbaum, whose well known pictures of sailors and warships and soldiers had reached us even in the far West, and whose charming family added so much to our pleasure.

Julian Hawthorne with his daughter Hildegarde, now so well known as a literary critic; Henry Loomis Nelson, whose fair daughter Margaret came to our little dances and promptly fell in love with a young, slim, straight Artillery officer. A case of

love at first sight, followed by a short courtship and a beautiful little country wedding at Miss Nelson’s home on the old Pelham Road, where Hildegarde Hawthorne was bridesmaid in a white dress and scarlet flowers (the artillery colors) and many famous literary people from everywhere were present.

Augustus Thomas, the brilliant playwright, whose home was near the Remingtons on Lathers’ Hill, and whose wife, so young, so beautiful and so accomplished, made that home attractive and charming.

Francis Wilson, known to the world at large, first as a singer in comic opera, and now as an actor and author, also lived in New Rochelle, and we came to have the honor of being remembered amongst his friends. A devoted husband and kind father, a man of letters and a book lover, such is the man as we knew him in his home and with his family.

And now came the delicious warm summer days. We persuaded the Quartermaster to prop up the little row of old bathing houses which had toppled over with the heavy winter gales. There were several bathing enthusiasts amongst us; we had a pretty fair little stretch of beach which was set apart for the officer’s’ families, and now what bathing parties we had! Kemble, the illustrator, joined our ranks–and on a warm summer bring the little old Tug Hamilton was gay with the artists and their families, the players and writers of plays, and soon you could see the little garrison hastening to the beach and the swimmers running down the long pier, down the run-way and off head first into the clear waters of the Sound. What a company was that! The younger and the older ones all together, children and their fathers and mothers, all happy, all well, all so gay, and we of the frontier so enamored of civilization and what it brought us!

There were no intruders and ah! those were happy days. Uncle Sam seemed to be making up to us for what we had lost during all those long years in the wild places.

Then Augustus Thomas wrote the play of “Arizona” and we went to New York to see it put on, and we sat in Mr. Thomas’ box and saw our frontier life brought before us with startling reality.

And so one season followed another. Each bringing its pleasures, and then came another lovely wedding, for my brother Harry gave up his bachelor estate and married one of the nicest and handsomest girls in Westchester County, and their home in New Rochelle was most attractive. My son was at the Stevens Institute and both he and Katharine were able to spend their vacations at David’s Island, and altogether, our life there was near to perfection.

We were doomed to have one more tour in the West, however, and this time it was the Middle West.

For in the autumn of ’96, Jack was ordered to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, on construction work.

Jefferson Barracks is an old and historic post on the Mississippi River, some ten miles south of St. Louis. I could not seem to take any interest in the post or in the life there. I could not form new ties so quickly, after our life on the coast, and I did not like the Mississippi Valley, and St. Louis was too far from the post, and the trolley ride over there too disagreeable for words. After seven months of just existing (on my part) at Jefferson Barracks, Jack received an order for Fort Myer, the end, the aim, the dream of all army people. Fort Myer is about three miles from Washington, D. C.

We lost no time in getting there and were soon settled in our pleasant quarters. There was some building to be done, but the duty was comparatively light, and we entered with considerable zest into the social life of the Capital. We expected to remain there for two years, at the end of which time Captain Summerhayes would be retired and Washington would be our permanent home.

But alas! our anticipation was never to be realized, for, as we all know, in May of 1898, the Spanish War broke out, and my husband was ordered to New York City to take charge of the Army Transport Service, under Colonel Kimball.

No delay was permitted to him, so I was left behind, to pack up the household goods and to dispose of our horses and carriages as best I could.

The battle of Manila Bay had changed the current of our lives, and we were once more adrift.

The young Cavalry officers came in to say good-bye to Captain Jack: every one was busy packing up his belongings for an indefinite period and preparing for the field. We all felt the undercurrent of sadness and uncertainty, but “a good health” and “happy return” was drunk all around, and Jack departed at midnight for his new station and new duties.

The next morning at daybreak we were awakened by the tramp, tramp of the Cavalry, marching out of the post, en route for Cuba.

We peered out of the windows and watched the troops we loved so well, until every man and horse had vanished from our sight. Fort Myer was deserted and our hearts were sad.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

My sister Harriet, who was visiting us at that time, returned from her morning walk, and as she stepped upon the porch, she said: “Well! of all lonesome places I ever saw, this is the worst yet. I am going to pack my trunk and leave. I came to visit an army post, but not an old women’s home or an orphan asylum: that is about all this place is now. I simply cannot stay!”

Whereupon, she proceeded immediately to carry out her resolution, and I was left behind with my young daughter, to finish and close up our life at Fort Myer.

To describe the year which followed, that strenuous year in New York, is beyond my power.

That summer gave Jack his promotion to a Major, but the anxiety and the terrible strain of official work broke down his health entirely, and in the following winter the doctors sent him to Florida, to recuperate.

After six weeks in St. Augustine, we returned to New York. The stress of the war was over; the Major was ordered to Governor’s Island as Chief Quartermaster, Department of the East, and in the following year he was retired, by operation of the law, at the age limit.

I was glad to rest from the incessant changing of stations; the life had become irksome to me, in its perpetual unrest. I was glad to find a place to lay my head, and to feel that we were not under orders; to find and to keep a roof-tree, under which we could abide forever.

In 1903, by an act of Congress, the veterans of the Civil War, who had served continuously for thirty years or more were given an extra grade, so now my hero wears with complacency the silver leaf of the Lieutenant-Colonel, and is enjoying the quiet life of a civilian.

But that fatal spirit of unrest from which I thought to escape, and which ruled my life for so many years, sometimes asserts its power, and at those times my thoughts turn back to the days when we were all Lieutenants together, marching across the deserts and mountains of Arizona; back to my friends of the Eighth Infantry, that historic regiment, whose officers and men fought before the walls of Chapultepec and Mexico, back to my friends of the Sixth Cavalry, to the days at Camp MacDowell, where we slept under the stars, and watched the sun rise from behind the Four Peaks of the MacDowell Mountains: where we rode the big cavalry horses over the sands of the Maricopa desert, swung in our hammocks under the ramadas; swam in the red waters of the Verde River, ate canned peaches, pink butter and commissary hams, listened for the scratching of the centipedes as they scampered around the edges of our canvas-covered floors, found scorpions in our slippers, and rattlesnakes under our beds.

The old post is long since abandoned, but the Four Peaks still stand, wrapped in their black shadows by night, and their purple colors by day, waiting for the passing of the Apache and the coming of the white man, who shall dig his canals in those arid plains, and build his cities upon the ruins of the ancient Aztec dwellings.

The Sixth Cavalry, as well as the Eighth Infantry, has seen many vicissitudes since those days. Some of our gallant Captains and Lieutenants have won their stars, others have been slain in battle.

Dear, gentle Major Worth received wounds in the Cuban campaign, which caused his death, but he wore his stars before he obeyed the “last call.”

The gay young officers of Angel Island days hold dignified commands in the Philippines, Cuba, and Alaska.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

My early experiences were unusually rough. None of us seek such experiences, but possibly they bring with them a sort of recompense, in that simple comforts afterwards seem, by contrast, to be the greatest luxuries.

I am glad to have known the army: the soldiers, the line, and the Staff; it is good to think of honor and chivalry, obedience to duty and the pride of arms; to have lived amongst men whose motives were unselfish and whose aims were high; amongst men who served an ideal; who stood ready, at the call of their country, to give their lives for a Government which is, to them, the best in the world.

Sometimes I hear the still voices of the Desert: they seem to be calling me through the echoes of the Past. I hear, in fancy, the wheels of the ambulance crunching the small broken stones of the malapais, or grating swiftly over the gravel of the smooth white roads of the river-bottoms. I hear the rattle of the ivory rings on the harness of the six-mule team; I see the soldiers marching on ahead; I see my white tent, so inviting after a long day’s journey.

But how vain these fancies! Railroad and automobile have annihilated distance, the army life of those years is past and gone, and Arizona, as we knew it, has vanished from the face of the earth.

THE END.

APPENDIX.

NANTUCKET ISLAND, June 1910.

When, a few years ago, I determined to write my recollections of life in the army, I was wholly unfamiliar with the methods of publishers, and the firm to whom I applied to bring out my book, did not urge upon me the advisability of having it

electrotyped, firstly, because, as they said afterwards, I myself had such a very modest opinion of my book, and, secondly because they thought a book of so decidedly personal a character would not reach a sale of more than a few hundred copies at the farthest. The matter of electrotyping was not even discussed between us. The entire edition of one thousand copies was exhausted in about a year, without having been carried on the lists of any bookseller or advertised in any way except through some circulars sent by myself to personal friends, and through several excellent reviews in prominent newspapers.

As the demand for the book continued, I have thought it advisable to re-issue it, adding a good deal that has come into my mind since its publication.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

It was after the Colonel’s retirement that we came to spend the summers at Nantucket, and I began to enjoy the leisure that never comes into the life of an army woman during the active service of her husband. We were no longer expecting sudden orders, and I was able to think quietly over the events of the past.

My old letters which had been returned to me really gave me the inspiration to write the book and as I read them over, the people and the events therein described were recalled vividly to my mind–events which I had forgotten, people whom I had forgotten–events and people all crowded out of my memory for many years by the pressure of family cares, and the succession of changes in our stations, by anxiety during Indian campaigns, and the constant readjustment of my mind to new scenes and new friends.

And so, in the delicious quiet of the Autumn days at Nantucket, when the summer winds had ceased to blow and the frogs had ceased their pipings in the salt meadows, and the sea was wondering whether it should keep its summer blue or change into its winter grey, I sat down at my desk and began to write my story.

Looking out over the quiet ocean in those wonderful November days, when a peaceful calm brooded over all things, I gathered up all the threads of my various experiences and wove them together.

But the people and the lands I wrote about did not really exist for me; they were dream people and dream lands. I wrote of them as they had appeared to me in those early years, and, strange as it may seem, I did not once stop to think if the people and the lands still existed.

For a quarter of a century I had lived in the day that began with reveille and ended with “Taps.”

Now on this enchanted island, there was no reveille to awaken us in the morning, and in the evening the only sound we could hear was the “ruck” of the waves on the far outer shores and the sad tolling of the bell buoy when the heaving swell of the ocean came rolling over the bar.

And so I wrote, and the story grew into a book which was published and sent out to friends and family.

As time passed on, I began to receive orders for the book from army officers, and then one day I received orders from people in Arizona and I awoke to the fact that Arizona was no longer the land of my memories. I began to receive booklets telling me of projected railroads, also pictures of wonderful buildings, all showing progress and prosperity.

And then came letters from some Presidents of railroads whose lines ran through Arizona, and from bankers and politicians and business men of Tucson, Phoenix and Yuma City. Photographs showing shady roads and streets, where once all was a glare and a sandy waste. Letters from mining men who knew every foot of the roads we had marched over; pictures of the great Laguna dam on the Colorado, and of the quarters of the Government Reclamation Service Corps at Yuma.

These letters and pictures told me of the wonderful contrast presented by my story to the Arizona of today; and although I had not spared that country, in my desire to place before my children and friends a vivid picture of my life out there, all these men seemed willing to forgive me and even declared that my story might do as much to advance their interests and the prosperity of Arizona as anything which had been written with only that object in view.

My soul was calmed by these assurances, and I ceased to be distressed by thinking over the descriptions I had given of the unpleasant conditions existing in that country in the seventies.

In the meantime, the San Francisco Chronicle had published a good review of my book, and reproduced the photograph of Captain Jack Mellon, the noted pilot of the Colorado river, adding that he was undoubtedly one of the most picturesque characters who had ever lived on the Pacific Coast and that he had died some years ago.

And so he was really dead! And perhaps the others too, were all gone from the earth, I thought when one day I received a communication from an entire stranger, who informed me that the writer of the review in the San Francisco newspaper had

been mistaken in the matter of Captain Mellon’s death, that he had seen him recently and that he lived at San Diego. So I wrote to him and made haste to forward him a copy of my book, which reached him at Yuma, on the Colorado, and this is what he wrote:

YUMA, Dec. 15th, 1908.

My dear Mrs. Summerhayes:

Your good book and letter came yesterday p. m., for which accept my thanks. My home is not in San Diego, but in Coronado, across the bay from San Diego. That is the reason I did not get your letter sooner.

In one hour after I received your book, I had orders for nine of them. All these books go to the official force of the Reclamation Service here who are Damming the Colorado for the Government Irrigation Project. They are not Damming it as we formerly did, but with good solid masonry. The Dam is 4800 feet long and 300 feet wide and 10 feet above high water. In high water it will flow over the top of the Dam, but in low water the ditches or canals will take all the water out of the River, the approximate cost is three million. There will be a tunnel under the River at Yuma just below the Bridge, to bring the water into Arizona which is thickly settled to the Mexican Line.

I have done nothing on the River since the 23rd of last August, at which date they closed the River to Navigation, and the only reason I am now in Yumai s trying to get something from Government for my boats made useless by the Dam. I expect to get a little, but not a tenth of what they cost me.

Your book could not have a better title: it is “Vanished Arizona” sure enough, vanished the good and warm Hearts that were here when you were. The People here now are cold blooded as a snake and are all trying to get the best of the other fellow.

There are but two alive that were on the River when you were on it. Polhemus and myself are all that are left, but I have many friends on this coast.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The nurse Patrocina died in Los Angeles last summer and the crying kid Jesusita she had on the boat when you went from Ehrenberg to the mouth of the River grew up to be the finest looking Girl in these Parts; She was the Star witness in a murder trial in Los Angeles last winter, and her picture was in all of the Papers.

I am sending you a picture of the Steamer “Mojave” which was not on the river when you were here. I made 20 trips with her up to the Virgin River, which is 145 miles above Fort Mojave, or 75 miles higher than any other man has gone with a boat: she was 10 feet longer than the “Gila” or any other boat ever on the River. (Excuse this blowing but it’s the truth).

In 1864 I was on a trip down the Gulf of California, in a small sail boat and one of my companions was John Stanton. In Angel’s Bay a man whom we were giving a passage to, murdered my partner and ran off with the boat and left Charley Ticen, John Stanton and myself on the beach. We were seventeen days tramping to a village with nothing to eat but cactus but I think I have told you the story before and what I want to know, is this Stanton alive. He belonged to New Bedford–his father had been master of a whale-ship.

When we reached Guaymas, Stanton found a friend, the mate of a steamer, the mate also belonged to New Bedford. When we parted, Stanton told me he was going home and was going to stay there, and as he was two years younger than me, he may still be in New Bedford, and as you are on the ground, maybe you can help me to find out.

All the people that I know praise your descriptive power and now my dear Mrs. Summerhayes I suppose you will have a hard time wading through my scrawl but I know you will be generous and remember that I went to sea when a little over nine

years of age and had my pen been half as often in my hand as a marlin spike, I would now be able to write a much clearer hand.

I have a little bungalow on Coronado Beach, across the bay from San Diego, and if you ever come there, you or your husband, you are welcome; while I have a bean you can have half. I would like to see you and talk over old times. Yuma is quite a place now; no more adobes built; it is brick and concrete, cement sidewalks and flower gardens with electric light and a good water system.

My home is within five minutes walk of the Pacific Ocean. I was born at Digby, Nova Scotia, and the first music I ever heard was the surf of the Bay of Fundy, and when I close my eyes forever I hope the surf of the Pacific will be the last sound that will greet my ears.

I read Vanished Arizona last night until after midnight, and thought what we both had gone through since you first came up the Colorado with me. My acquaintance with the army was always pleasant, and like Tom Moore I often say:

Let fate do her worst, there are relics of joy Bright dreams of the past which she cannot destroy! Which come in the night-time of sorrow and care And bring back the features that joy used to wear. Long, long be my heart with such memories filled!

I suppose the Colonel goes down to the Ship Chandler’s and gams with the old whaling captains. When I was a boy, there was a wealthy family of ship-owners in New Bedford by the name of Robinson. I saw one of their ships in Bombay, India,

that was in 1854, her name was the Mary Robinson, and altho’ there were over a hundred ships on the bay, she was the handsomest there.

Well, good friend, I am afraid I will tire you out, so I will belay this, and with best wishes for you and yours,

I am, yours truly, J. A. MELLON.

P. S.–Fisher is long since called to his Long Home.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I had fancied, when Vanished Arizona was published, that it might possibly appeal to the sympathies of women, and that men would lay it aside as a sort-of a “woman’s book”–but I have received more really sympathetic letters from men than I have from women, all telling me, in different words, that the human side of the story had appealed to them, and I suppose this comes from the fact that originally I wrote it for my children, and felt perfect freedom to put my whole self into it. And now that the book is entirely out of my hands, I am glad that I wrote it as I did, for if I had stopped to think that my dream people might be real people, and that the real people would read it, I might never have had the courage to write it at all.

The many letters I have received of which there have been several hundred I am sure, have been so interesting that I reproduce a few more of them here:

FORT BENJAMIN HARRISON, INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA. January 10, 1909.

My dear Mrs. Summerhayes:

I have just read the book. It is a good book, a true book, one of the best kind of books. After taking it up I did not lay it down till it was finished–till with you I had again gone over the malapais deserts of Arizona, and recalled my own meetings with you at Niobrara and at old Fort Marcy or Santa Fe. You were my cicerone in the old town and I couldn’t have had a better one–or more charming one.

The book has recalled many memories to me. Scarcely a name you mention but is or was a friend. Major Van Vliet loaned me his copy, but I shall get one of my own and shall tell my friends in the East that, if they desire a true picture of army life as it appears to the army woman, they must read your book.

For my part I feel that I must congratulate you on your successful work and thank you for the pleasure you have given me in its perusal.

With cordial regard to you and yours, and with best wishes for many happy years.

Very sincerely yours, L. W. V. KENNON, Maj. 10th Inf.

HEADQUARTERS THIRD BRIGADE, NATIONAL GUARD OF PENNSYLVANIA, WILKES-BARRE, PENNSYLVANIA. JANUARY 19, 1908.

Dear Madam:

I am sending you herewith my check for two copies of “Vanished Arizona.” This summer our mutual friend, Colonel Beaumont (late 4th U. S. Cav.) ordered two copies for me and I have given them both away to friends whom I wanted to have read your delightful and charming book. I am now ordering one of these for another friend and wish to keep one in my record library as a memorable story of the bravery and courage of the noble band of army men and women who helped to blaze the pathway of the nation’s progress in its course of Empire Westward.

No personal record written, which I have read, tells so splendidly of what the good women of our army endured in the trials that beset the army in the life on the plains in the days succeeding the Civil War. And all this at a time when the nation and its people were caring but little for you all and the struggles you were making.

I will be pleased indeed if you will kindly inscribe your name in one of the books you will send me.

Sincerely Yours, C. B. DOUGHERTY, Brig. Gen’l N. G. Pa. Jan. 19, 1908

SCHENECTADY, N. Y. June 8th, 1908.

Mrs. John W. Summerhayes, North Shore Hill, Nantucket, Mass.

My Dear Mrs. Summerhayes:

Were I to say that I enjoyed “Vanished Arizona, “I should very inadequately express my feelings about it, because there is so much to arouse emotions deeper than what we call “enjoyment;” it stirs the sympathies and excites our admiration for your courage and your fortitude. In a word, the story, honest and unaffected, yet vivid, has in it that touch of nature which makes kin of us all.

How actual knowledge and experience broadens our minds! Your appreciation of, and charity for, the weaknesses of those living a lonely life of deprivation on the frontier, impressed me very much. I wish too, that what you say about the canteen could be published in every newspaper in America.

Very sincerely yours,

M. F. WESTOVER, Secretary Gen’l Electric Co.

THE MILITARY SERVICE INSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES.

Governor’s Island, N. Y. June 25, 1908.

Dear Mrs. Summerhayes:

I offer my personal congratulations upon your success in producing a work of such absorbing interest to all friends of the Army, and so instructive to the public at large.

I have just finished reading the book, from cover to cover, to my wife and we have enjoyed it thoroughly.

Will you please advise me where the book can be purchased in New York, or otherwise mail two copies to me at 203 W. 54th Street, New York City, with memo of price per copy, that I may remit the amount.

Very truly yours,

T. F. RODENBOUGH, Secretary and Editor (Brig. Gen’l. U. S. A.)

YALE UNIVERSITY, NEW HAVEN, CONN.

May 15, 191O.

Dear Mrs. Summerhayes:

I have read every word of your book “Vanished Arizona” with intense interest. You have given a vivid account of what you actually saw and lived through, and nobody can resist the truthfulness and reality of your narrative. The book is a real contribution to American history, and to the chronicles of army life.

Faithfully yours, WM. LYON PHELPS,

[Professor of English literature at Yale University.]

LONACONING, MD., Jan. 2, 1909.

Col. J. W. Summerhayes, New Rochelle, N. Y.

Dear Sir:

Captain William Baird, 6th Cavalry, retired, now at Annapolis, sent me Mrs. Summerhayes’ book to read, and I have read it with delight, for I was in “K” when Mrs. Summerhayes “took on” in the 8th. Myself and my brother, Michael, served in “K” Company from David’s Island to Camp Apache. Doubtless you have forgotten me, but I am sure that you remember the tall fifer of “K”, Michael Gurnett. He was killed at Camp Mohave in Sept. 1885, while in Company “G” of the 1st Infantry. I was five years in “K”, but my brother re-enlisted in “K”, and afterward joined the First. He served in the 31st, 22nd, 8th and 1st.

Oh, that little book! We’re all in it, even poor Charley Bowen. Mrs. Summerhayes should have written a longer story. She soldiered long enough with the 8th in the “bloody 70’s” to be able to write a book five times as big. For what she’s done, God bless her! She is entitled to the Irishman’s benediction: “May every hair in her head be a candle to light her soul to glory.” We poor old Regulars have little said about us in print, and wish to God that “Vanished Arizona” was in the hands of every old veteran of the “Marching 8th.” If I had the means I would send a copy to our 1st Serg’t Bernard Moran, and the other old comrades at the Soldiers’ Home. But, alas, evil times have fallen upon us, and–I’m not writing a jeremiad–I took the book from the post office and when I saw the crossed guns and the”8″ there was a lump in my throat, and I went into the barber shop and read it through before I left. A friend of mine was in the shop and when I came to Pringle’s death, he said, “Gurnett, that must be a sad book you’re reading, why man, you’re crying.”

I believe I was, but they were tears of joy. And, Oh, Lord, to think of Bowen having a full page in history; but, after all, maybe he deserved it. And that picture of my company commander! [Worth]. Long, long, have I gazed on it. I was only

sixteen and a half years old when I joined his company at David’s Island, Dec. 6th, 1871. Folliot A. Whitney was 1st lieutenant and Cyrus Earnest, 2nd. What a fine man Whitney was. A finer man nor truer gentleman ever wore a shoulder strap. If he had been company commander I’d have re-enlisted and stayed with him. I was always afraid of Worth, though he was always good to my brother and myself. I deeply regretted Lieut. Whitney’s death in Cuba, and I watched Major Worth’s career in the last war. It nearly broke my heart that I could not go. Oh, the rattle of the war drum and the bugle calls and the marching troops, it set me crazy, and me not able to take a hand in the scrap.

Mrs. Summerhayes calls him Wm. T. Worth, isn’t it Wm. S. Worth?

The copy I have read was loaned me by Captain Baird; he says it’s a Christmas gift from General Carter, and I must return it. My poor wife has read it with keen interest and says she: “William, I am going to have that book for my children,” and

she’ll get it, yea, verily! she will.

Well, Colonel, I’m right glad to know that you are still on this side of the great divide, and I know that you and Mrs. S. will be glad to hear from an old “walk-a-heap” of the 8th. I am working for a Cumberland newspaper–Lonaconing reporter–and

I will send you a copy or two of the paper with this. And now, permit me to subscribe myself your

Comrade In Arms,

WILLIAM A. GURNETT.

Dear Mrs. Summerhayes:

Read your book–in fact when I got started I forgot my bedtime (and you know how rigid that is) and sat it through. It has a bully note of the old army–it was all worthwhile–they had color, those days.

I say–now suppose you had married a man who kept a drug store–see what you would have had and see what you would have missed.

Yours, FREDERIC REMINGTON.

Among the wounded, Brig. Gen. Pettigrew of SC & Lt. Col. Bull of the 35th Georgians. Pettigrew had given up all his side arms to some of his people before they ran away, in anticipation of being taken prisoner, & had only his watch, which of course I returned to him. Pettigrew will get well. Bull had his side arms, of which I allowed Corp. Summerhayes, his captor, to keep his pistol, an ordinary affair, while I kept his sword, an ordinary US infantry sword, which I intended to send as a present to you, but the Col., knowing [p.129] his family’s address, wants me to send it to them, & as the poor fellow is dead, of course I can’t hesitate to do any thing which would comfort his family. His scabbard, however, I found very convenient, as mine got broken in the battle and I threw it away. I am going to send you, instead, a short rifle which I took from a Hampton’s] Legion fellow, who were all around with them & the sword bayonet. The rest of the rifles we of course turned over to the col., as in duty bound, except one revolving Colt’s rifle, 5 barrels, worth $60 or $70 apiece…which one of my men took from a dying officer, & which I let him keep as a reward of valor.”

–Robert Garth Scott, ed., Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Major Henry Livermore Abbott (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991) pp. 128-129.

20th Mass. Corporal John W. Summerhayes’ account:

“Lieutenant Abbott ordered me into the woods, with a file of men, to bring out all the wounded, and rebels, that could be found. As I started, seven came out, belonging to the Hampton Legion, SC, the finest brigade in the rebel service. After coming in with them, I advanced into the woods, and hearing a groaning, walked up and there found Lieut. Col. Bull of the 34th Georgia [sic]. I took his sword and revolver, and sent him in. After taking several more, I fell in with one, whom I knew, although his side arms were gone, was of some high rank, and so he proved to be. Although he would not give me any answers, the Colonel was more fortunate, for he found out that it was Brigadier General Pettigrew, of the State of South Carolina.”

–Richard F. Miller and Robert F. Mooney, The Civil War: The Nantucket Experience (Nantucket: Wesco Publishing, 1994) pp. 187.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL JOHN W. SUMMERHAYES

May 9, 1911

Lieutenant Colonel John W. Summerhayes, U.S.A., retired, who served through two wars and the Indian Campaigns, died yesterday at his home in Nantucket, Rhode Island, of heart disease. He was in his seventy-fifth year. The interment will take place on Saturday at the National Cemetery in Arlington.

Colonel Summerhayes was born in Nantucket. He enlisted when Fort Sumter was fired upon and served through the Civil War, having attained the rank of Captain of Company L, Twentieth Massachusetts Infantry, when its close came. He was brevetted Major of Volunteers for gallantry. After the mustering our of the volunteer army, he served with the Eighth and Twenty-third Infantry on the frontier. He was brevetted Captain for bravery at Balls’s Bluff and Cold Harbor, and in 1899 was attached to the Quartermaster’s Department with the rank of Captain. During the Spanish-American War he inspected and outfitted the ships that were purchased by the Government for transport, supply and hospital ships. Before this he had been in command at David’s Island, Long Island Sound. During this war he was commissioned Major of Volunteers and assigned to New York State.

SUMMERHAYES, MARTHA W W/O JOHN W

DATE OF DEATH: 05/11/1926

DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

BURIED AT: SECTION WE SITE 153-6

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

WIFE OF JOHN W. SUMMERHAYES CAPT ASST QM

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard