Members of the 1st Lt. James Reese Europe American Legion Post 5 in Washington honor their namesake with a wreath at his grave in Arlington National Cemetery, Va. Europe was a World War I hero and famous ragtime musician and military bandmaster. Photo by Rudi Williams.

By Rudi Williams

American Forces Press Service

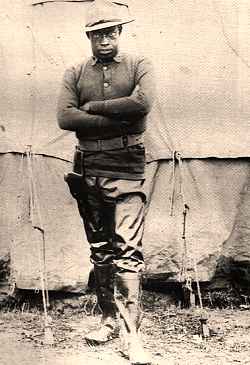

WASHINGTON, June 5, 2000 — The name “Lt. James Reese Europe” etched into a graying, weathered tombstone doesn’t mean anything to most visitors to Arlington National Cemetery. It’s just an obscure name among thousands on grave markers throughout the huge military burial ground.

Of Europe, the late ragtime and jazz composer and performer pianist Eubie Blake once said, “People don’t realize yet today what we lost when we lost Jim Europe. He was the savior of Negro musicians … in a class with Booker T. Washington and Martin Luther King Jr.”

Europe is credited with bringing ragtime out of the bordellos and juke joints into mainstream society and elevating African American music into an accepted art form. He was an unrelenting fighter for the dignity of African American musicians and for them to be paid on the same scale as their white peers.

The French government called him a battlefield hero. Before the war, however, he was a household name in New York’s music world and on the dance scene nationwide. According to books about ragtime and early jazz, James Reese Europe was the most respected black bandleader of the “teens” when the United States

entered World War I. Both his battlefield heroism and his music fell into obscurity after his untimely and tragic death at 39 on May 9, 1919.

The son of a former slave father and a “free” mother, Europe was born in Mobile, Ala., on Feb. 22, 1881. Lorraine and Henry Europe were both musicians and encouraged their children’s talents.

When he was about 10, the family moved to Washington and lived a few houses from Marine Corps bandmaster John Philip Sousa. He and his sister, Mary, took violin and piano lessons from the Marine band’s assistant director, Enrico Hurlei. Europe won second place in a music composition contest at age 14. Mary captured first place.

Europe moved to New York City in 1903 to pursue a musical career. Work as a violinist was scarce, so he turned to the piano and found work in several cabarets. He helped found an African American fraternity known as “the Frogs,” and, in 1910, established the Clef Club, the first African American music union and booking agency.

His popularity soared as a bandleader and arranger for the internationally acclaimed dance duo Irene and Vernon Castle. The Castles and Europe helped pioneer modern dance by popularizing the foxtrot and other dances.

On May 2, 1912, Europe’s Clef Club Orchestra became the first African American band and the first jazz band to play in New York City’s famous Carnegie Hall. The orchestra’s debut there was so well received that it was booked for two more engagements in 1913 and 1914.

Europe’s compositions and arrangements of familiar tunes were played with a jazz twist long before the “Jazz Age.” His style was between the syncopated beat of ragtime and the syncopated improvisation of jazz. He became popular in France using that same style as leader of the 369th Infantry Regiment band during World War I.

He enlisted as a private in the 15th Infantry, a black New York National Guard outfit, on Sept. 18, 1916. Europe accomplished something only a few African Americans did in those days: He attended officers training and was commissioned a lieutenant.

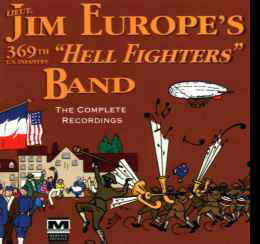

The 15th Infantry was later redesignated the 369th Infantry, which the French nicknamed “The Harlem Hellfighters” after the black soldiers showed their mettle in combat.

Europe’s regimental commander, Col. William Hayward, asked the new lieutenant to organize “the best damn brass band in the United States Army.” With the promise of extra money to attract first-class musicians, Europe recruited musicians from Harlem and reportedly put together one of the finest military bands that ever existed. He even recruited woodwind players from Puerto Rico because there weren’t enough in Harlem. Europe also recruited singers, comedians, dancers and others who could entertain troops. He recruited the best drum major he could find — Harlem dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

When the 369th and its band arrived in France, they were assigned to the 16th “Le Gallais” Division of the Fourth French Army because white U.S. Army units refused to fight alongside them. Trained to command a machine gun company, Europe learned to fire French machine guns and became the first American officer and first African American to lead troops in battle during the war.

The Harlem Hellfighters would serve 191 days in combat, longer than any other U.S. unit, and reputedly never relinquished an inch of ground. The men earned 170 French Croix de Guerres for bravery. One of their commanding officers, Col. Benjamin O. Davis Sr., would become the Army’s first black general in 1940.

Europe was gassed while leading a daring nighttime raid against the Germans. While recuperating in a French hospital, he penned the song “One Patrol in No Man’s Land.”

Europe and his musicians were ordered to the rear in August 1918 to entertain thousands of soldiers in camps and hospitals. They also performed for high-ranking military and civilian officials and for French citizens in cities across France. After Germany surrendered, the Hellfighters Band became popular performing throughout Europe. When the regiment returned home in the spring of 1919, it paraded up New York’s 5th Avenue to Harlem led by the band playing its raggedy tunes to the delight of more than a million spectators.

Back in America, Europe found himself even more popular than before he went to war. He recorded “One Patrol in No Man’s Land”; it became a nationwide hit.

Europe ironically survived being shot at and gassed in the trenches of France only to die on May 9, 1919, at the hands of one of his own men. A deranged drummer named Herbert Wright cut Europe’s jugular vein with a penknife while the bandleader was preparing for a show at Mechanics Hall in Boston. Wright had been angry because he thought Europe favored his twin brother over him.

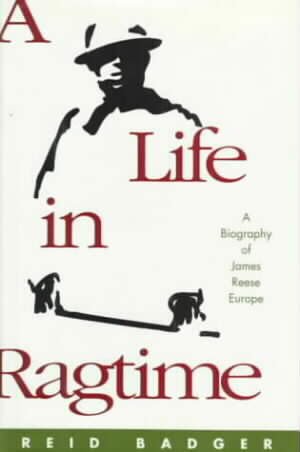

R. Reid Badger noted in his book “A Life in Ragtime” that Europe received the first public funeral for a black man in New York City on May 13, 1919. Thousands of fans, black and white, turned out to pay their respect.

In late February 2000, a busload of aging legionnaires of the 1st Lt. James Reese Europe American Legion Post 5 in Washington carefully ambled up a slippery, wet grassy hill at Arlington National Cemetery. Reaching a weathered headstone engraved with “Lt. James Reese Europe – Feb. 22, 1881 – May 14, 1919,” they laid a wreath at the grave. Europe has a larger headstone than most — it was erected in July 1943 to replace a small government-issued 1919 grave marker.

“Our post was named in honor of James Reese Europe in 1919, but to my knowledge, no one ever stopped to put a flower on his grave,” said post commander Thomas L. Campbell. “Frankly, we didn’t know much about him until we read a story about him in the American Legion magazine about a year ago. I thought it was time we did something to show some appreciation for the man whose name is on our post.”

Campbell said the French government bestowed one its highest military awards on Europe and the 369th Infantry. The Dec. 9, 1918, citation to the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Star reads in part:

“This officer (Lt. James Reese Europe), a member of the 369th Infantry Regiment of the 93rd Infantry Division, American Expeditionary Forces, was the first black American to lead United States troops in battle during World War I. The unit, under fire for the first time, captured some powerful and energetically defended enemy positions, took the village of Bechault by main force, and brought back six cannons, many machine guns and a number of prisoners.”

After their wreath-laying ceremony, the legionnaires attended a jazz concert performed by the Army Band’s jazz ensemble at Fort Myer, Va., in Europe’s honor.

Europe’s only child, James R. Europe Jr. of North Bellmore, Long Island, N.Y., had been invited to the ceremony, but was unable to attend. The 83-year-old told the legionnaires his health made the trip inadvisable.

The younger Europe, a World War II Merchant Marine lieutenant, is a former member of the New York police and fire departments, served as chairman of the Nassau County Human Rights Commission from 1962 to 1975. The World War I bandleader’s descendants include four granddaughters and a grandson, five great- grandchildren and seven great-great-grandchildren.

Interest has grown in Europe’s music in recent years and his recordings are being remastered and reissued on CDs. The Internet is loaded with material about James Reese Europe. Using the search engine, key in James Reese Europe.

Courtesy of the American Legion

James Reese Europe was born in Mobile, Ala., in 1880. His family moved to Washington, D.C. when James was nine years old.

Europe enlisted in the Army in 1916 and helped organize a band for the 15th Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard—a black regiment for a segregated force. As a soldier, Europe performed valiantly. In the spring of 1918 he led troops under fire. The 15th became the storied 369th “Harlem Hellfighters,” who never relinquished an inch of ground they were expected to hold. He also participated in a daring night raid on German positions and was himself gassed in the course of battle. But Badger says his main value to the Army and the war effort was as a band leader and role model.

Col. William Hayward, the 369th’s CO, made it possible for Europe to form the band and allowed Europe to recruit musicians from Puerto Rico. Under Europe’s leadership they became a top-flight military band that played familiar tunes with a unique jazz twist. “Responses to Europe’s band were so strong, they were sent all around France to perform for troops,” Badger says.

The French people heard an earful, but perhaps not as much as they wanted. A story in the June 10, 1918, edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported, “The ‘jazz germ’ hit them, and it seemed to find a vital spot, loosening all muscles and causing what is known in America as an ‘eagle rocking it,’” the article read. “All through France the same thing happened. Troop trains carrying Allied soldiers from everywhere passed us en route, and every head stuck out a window when we struck up a good old Dixie tune. Even German prisoners forgot they were prisoners, dropped their work to listen and pat their feet to the stirring American tunes…I was satisfied that American music would someday be the world’s music.”

While recuperating in a French hospital after being gassed, Europe wrote “On Patrol in No Man’s Land,” which quickly became popular in the United States. Europe perhaps sensed the response his band provoked overseas would follow them home.

He returned home with his fellow veterans to a ticker tape parade in Manhattan in February 1919. The parade created such enthusiasm that newspapers reported the event as a ‘near riot.’ ”

On May 9, Europe was preparing for a performance at Mechanics Hall in Boston. Governor Calvin Coolidge had invited Europe perform on the steps of the State House the next day.

Europe’s promise was never brighter and his popularity never greater. But Herbert Wright, one of Europe drummers, harbored a rage against the band leader unleashed with little warning. After a rehearsal, Wright claimed the bandmaster had been showing favoritism to his twin brother, who was another percussionist with the band. Wright suddenly, and in full view of witnesses, stabbed Europe in the neck with a pen knife and left what appeared to be a superficial wound.

But the bleeding wouldn’t stop. Europe died that day at a local hospital.

He received the first public funeral for a black man in New York City on May 13, according to Reid in his Europe biography, “A Life in Ragtime.”

Thousands of people, black and white, turned out to pay their respects in a procession that was his final parade before burial at Arlington. A movement for a “National Musical Memorial Day” in his honor faded, as did the effort to fund a Harlem music school intended to carry his name.

But in Pennsylvania Railroad boxcar 10196, on June 14, a month and a day after Europe’s death, James Reese Europe Post 5 was organized at Washington Navy Yard. There are 275 current members of the Post, which was once noted for the

magnificent bands it sponsored and for the battles it waged for civil rights and working for integration of the armed forces during the 1930s, finally realized a decade later.

Music was always important at the Post. In 1935 a member dropped dead during a parade in Washington, and his widow asked that he be buried in his drum and Bugle Corps uniform. The commander granted the request.

It was the sort of honor James Reese Europe would have understood.

Courtesy of the Washington Post, 26 February 2000:

Jazz Pioneer Remembered

Lieutenant James Reese Europe, the D.C. musician who helped introduce jazz to

the continent of Europe just after World War I, was remembered Friday, February 25, 2000, with a memorial service at Arlington National Cemetery, where he is buried.

The service, organized by the American Legion, was a bit abbreviated by the cold, wet weather, but the part Europe would have liked was the tribute concert that followed at Fort Myer’s Brucker Hall.

The U.S. Army band Pershing’s Own entertained the audience with a selection of music associated with Europe.

After the armistice was signed, Europe, a jazz band leader known as “Big Jim,” formed the 369th Infantry’s Hell Fighters Band that toured France. Europe, who was born in Alabama but raised in Washington, died in 1919.

From Booklist: December 1, 1994

James Reese Europe was a pivotal composer-conductor who helped jazz’s evolution away from ragtime–a significant-enough accomplishment, especially considering Reese’s relatively short life (he was murdered at 39 in 1919). But Badger’s engrossing biography proves that Europe was an American hero both in front of and far away from an orchestra. Badger’s analyses of Europe’s compositions are well-informed and suitably augmented with commentary from such notable collaborators as Eubie Blake. Badger shows, too, that Europe helped restyle modern dance through his collaborations with Vernon and Irene Castle; and he includes chapters on the Clef Club, one of the earliest African American musicians’ unions, which Europe helped create. Europe’s career took an incredible turn during World War I, an episode Badger carefully details: while the triumphs of the all-black 369th Infantry Regiment are legendary, few know that Europe was the first African American officer to lead troops in combat during the war. A Life in Ragtime is one of the most important works of jazz scholarship to emerge in quite some time.

From Kirkus Reviews , October 15, 1994:

Badger (American Studies/University of Alabama) restores an important, forgotten chapter in African-American musical history. Europe was one of the pioneering omposers, bandleaders, and musical factotums in turn-of-the-century America. Raised in Washington, D.C., he was exposed to a rich musical life in church, home, and public concerts. Around 1903, he left the capital for New York City (where his older brother was established as a theatrical pianist) and was soon working as a bandleader, arranger, and composer. Europe was a born organizer, helping to found a black theatrical fraternity known humorously as “The Frogs” and then, in 1910, the famous Clef Club, the first union of African-American musicians. In 1914, he joined forces with Vernon and Irene Castle, who were just beginning to perform the new black-influenced dances for high society. He introduced them to W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues,” suggesting they create a new dance to accompany its changing meters; the result was the fox-trot, the popular dance team’s most enduring legacy.

During WW I, Europe was a machine- gunner with the 369th Regiment, an all-black company that fought as part of the French army (because the Americans feared integrating their ranks). Ironically, after surviving front-line duty, Europe was knifed by a disgruntled band member in 1919; he died at age 39. Europe, like Handy, his near-contemporary, hoped to mold a black concert music, drawing on 19th-century European roots, that would “uplift his race.” Although elements of ragtime and jazz crept into his music, he favored the sentimental parlor style of playing and singing that was the rage in late Victorian days. His musical legacy has been more or less forgotten, although without his pioneering work the success of Paul Whiteman’s orchestra in the 1920s (and Duke Ellington’s in the ’30s) surely couldn’t have occurred. Will appeal to fans of early jazz, African-American history, and 20th-century culture.

EUROPE, JAMES REESE

- FORMERLY 1ST LT 15 NY NG SUBSEQUENTLY WORLD 369 US INF

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/09/1919

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SECTION E DIV SITE 3576

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard