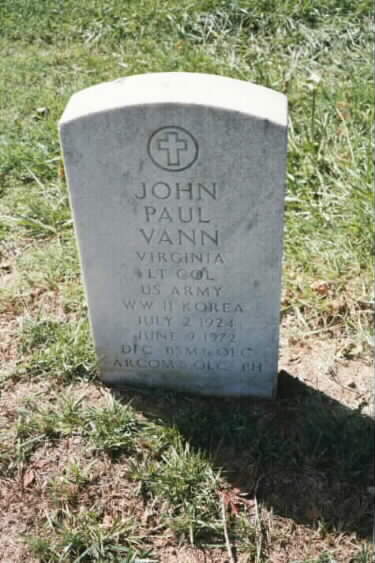

Born at Norfolk, Virginia, July 2, 1924, he was killed in the crash of a helicopter in Vietnam on June 9, 1972.

He was a career Army officer who served also in the Korean War. He was forced from the Army because he was critical of the way that the war in Vietnam was being conducted. He returned to Vietnam as an official of the Agency for International Development (AID), and he was acting in that capacity when killed.

He was buried on June 16, 1972 in Section 11 of Arlington National Cemetery.

For more about him, read the book “A Bright And Shining Lie.”

John Paul Vann (July 2, 1924 – June 9, 1972) was a Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Army, later retired, who became well-known for his role in the Vietnam War.

Vann was born in Norfolk, Virginia, and grew up in near-poverty. Through the patronage of a wealthy member of his church he was able to attend boarding school at a junior college. With the onset of World War II, Vann sought to become a pilot.

In 1943, at the age of 18, he earned a degree and managed to enlist in the Army Air Corps. Vann underwent pilot training, then transferred to navigation school, and graduated as a second lieutenant in 1945. The war ended before he could see action, however. He married Mary Jane Allen at the end of that year; they would go on to have five children together.

When the Air Corps broke away from the Army in 1947 to form the separate Air Force, Vann chose to remain in the Army and transferred to the infantry. He was assigned to Korea, and then Japan, as a logistics officer. When the Korean War began in June 1950, Vann coordinated the transportation of his 25th Infantry Division to Korea. Vann joined his unit, which was placed on the critical Pusan Perimeter until the amphibious Inchon landing relieved the beleaguered forces. In late 1950, in the wake of China’s entrance into the war and the retreat of allied forces, now-Captain Vann was given his first command, a Ranger company. He led the unit on reconnaissance missions behind enemy lines for three months, before a serious illness in one of his children resulted in his transfer back to the US.

In 1954 Vann joined the 16th Infantry Regiment in Schweinfurt, Germany, becoming the head of the regiment’s Heavy Mortar Company. In 1955 he was promoted to Major and transferred to Headquarters US Army Europe at Heidelberg where he returned to logistics work. In 1957 Vann returned to the US to attend the Command and General Staff College, a requirement for promotion to Lieutenant Colonel, and in 1961 Vann was promoted.

Vann was assigned to South Vietnam in 1962 as an advisor to Col. Huynh Van Cao, commander of the ARVN 7th Division. In the thick of the anti-guerrilla war against the Viet Cong, Vann became cognizant of the ineptness with which the war was being prosecuted, in particular the disastrous Battle of Ap Bac, Jan. 2, 1963. Vann, directing the battle from a spotter plane overhead, earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for his bravery in taking enemy fire. He attempted to draw public attention to the problems, through press contacts such as New York Times reporter David Halberstam, focusing much of his ire on the US commander in the country, MACV chief Gen. Paul D. Harkins. Vann was forced from his advisor position in March 1963 and left the Army within a few months.

Vann returned to Vietnam in March 1965 as an official of the Agency for International Development (AID). After an assignment as province senior adviser, Vann was made Deputy for CORDS in the Third Corps Tactical Zone of Vietnam, which consisted of the twelve provinces north and west of Saigon– the most important part of South Vietnam. CORDS (Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support)was an integrated group that consisted of USAID, US Information Service, CIA, and State Department along with U.S. Army personnel to provide needed manpower. Among other undertakings, CORDS was responsible for the Phoenix program, which involved the assination of the Viet Cong infrastructure.

Vann served as Deputy for CORDS III (i.e., commander of all civilian and military advisers in the Third Corps Tactical Zone)until November, 1968 when he was assigned to the same position in Four Corps, which consisted of the provinces south of Saigon in the Mekong Delta.

Vann was highly respected by a large segment of officers and civilians who were involved in the broader political aspects of the war because he favored small unit, aggressive patrolling over grandiose, large unit engagements. He was respectful of the Vietnam soldiers notwithstanding their frequent lackluster performance and he was committed to training and strengthing the morale and committment of the Vietnamese troops. He encouraged his personnel to engage themselves in Vietnamese society as much as possible, and he constantly briefed that the Vietnam war must be envisaged as a long war at a lower level of engagement rather than a short war at a big-unit, high level of engagement.

On one of his trips back to the U.S. in 1968, Vann was asked by Eugene Rostow, an advocate of more troops and higher levels of engagement and one of President Johnson’s senior Whitehouse advisors,whether the war would be over in six months: “No,” replied Vann, “I think we can last a lot longer than that!” Vann’s wit and iconoclasm did not endear him to many military and civilian careerists, but he was a hero to many young civilian and military officers who understood the limits of conventional warfare in the irregular environment of Vietnam.

After his assignment to IV Corps, Vann was assigned as the senior American advisor in II Corps Military Region in the early 1970’s when the war was winding down and troops were being withdrawn. For that reason, his new job put him in charge of all United States personnel in his region, where he advised the ARVN Commander to the region and became the first American civilian to command U.S. regular troops in combat. His position was the job of a two-star General. After the Battle of Kontum, he was killed when his helicopter was shot down.

Vann was buried on June 16, 1972 in Section 11 of Arlington National Cemetery. His funeral was attended by such notables as Major General Edward Lansdale, Lieutenant Colonel Lucien Conein, Senator Edward Kennedy, and Daniel Ellsberg.

On June 18, 1972, President Richard Nixon posthumously awarded Vann the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian citation, for his ten years of service as a top American in South Vietnam. For his actions from April 23 & April 24, 1972, Vann, ineligible for the Medal of Honor as a civilian, was also awarded (posthumously) the Distinguished Service Cross, the only civilian so honored in Vietnam.

Journalist Neil Sheehan wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnam history and biography of Vann, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam.

Vann, John Paul

U.S. Civilian

Agency for International Development, United States Department of State

Date of Action: April 22 & 23, 1972

Citation:

The Distinguished Service Cross is presented to Mr. John Paul Vann, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service as a United States civilian working with the Agency for International Development, United States State Department, in the Republic of Vietnam.

Mr. Vann distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism in action during the period 23 April to 24 April 1972.

During an intense enemy attack by mortar, artillery and guided missiles on the 22d Army of the Republic of Vietnam Division forward command post at Tan Canh, Mr. Vann chose to have his light helicopter land in order to assist the Command Group.

After landing, he ordered his helicopter to begin evacuating civilian employees and the more than fifty wounded soldiers while he remained on the ground to assist in evacuating the wounded and provide direction to the demoralized troops. With total disregard for his own safety, Mr. Vann continuously exposed himself to enemy artillery and mortar fire. By personally assisting the wounded and giving them encouragement, he assured a calm and orderly evacuation. As the enemy fire increased in accuracy and tempo, he set the example by continuing to assist in carrying the wounded to the exposed helipad. His skillful command and control of the medical evacuation ships during the extremely intense enemy artillery fire enabled the maximum number of soldiers and civilians to be safely evacuated. On the following day the enemy launched a combined infantry tank team attack at the 22nd Division Headquarters compound.

Shortly thereafter, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam defense collapsed, enemy tanks penetrated the compound, and the enemy forces organized .51 caliber anti-aircraft positions in and around the compound area. To evade the enemy the United States advisors moved under heavy automatic weapons fire to an area approximately 500 meters away from the compound. Completely disregarding the intense small arms and .51 caliber anti-aircraft fire and the enemy tanks, Mr. Vann directed his helicopter toward the general location of the United States personnel, who were forced to remain in a concealed position. In searching for the advisors’ location, his helicopter had to maintain an altitude and speed which made it extremely vulnerable to all forms of enemy fire. Undaunted, he continued his search until he located the advisors’ position. Making an approach under minimal conditions he landed and quickly pulled three United States advisors into the aircraft. As the aircraft began to ascend, five Army of the Republic of Vietnam soldiers were clinging to the skids. Although the total weight far exceeded the maximum allowable for the light helicopter, Mr. Vann chose to save the Army of the Republic of Vietnam personnel holding on to the skids by having the helicopter maneuver without sharp evasive action. Consequently, the aircraft sustained numerous hits.

In order to return to Tan Canh as soon as possible to save the remaining advisors and to save the soldiers clinging to the skids, Mr. Vann detoured his aircraft from Kontum to a nearby airfield. Throughout this time Mr. Vann was directing air strikes on enemy tanks and anti-aircraft positions. While en route back to Tam Canh, Mr. Vann’s helicopter was struck by heavy anti-aircraft fire, which forced it to land.

Throughout the day Mr. Vann assisted in extracting other advisors and soldiers in the Dak To area. On one such occasion another group of army of the Republic of Vietnam soldiers attempted to cling to one side of his helicopter, caused it to crash. Undaunted by these occurrences, Mr. Vann continued directing air strikes and maneuvering friendly troops to safe areas. Because of his fearless and tireless efforts, Mr. Vann was directly responsible for saving hundreds of personnel from the enemy onslaught. His conspicuous gallantry and extraordinary heroic actions reflect great credit upon him and the United States of America.

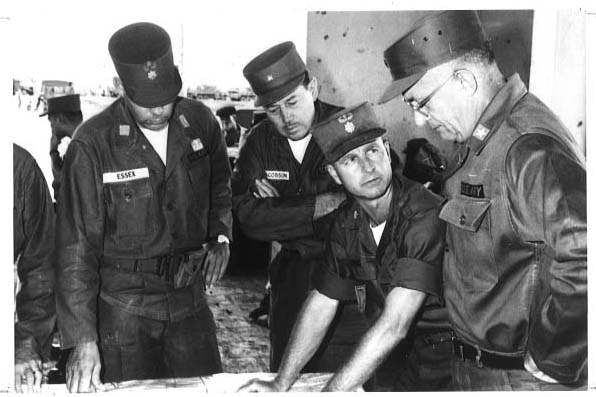

John Paul Vann, Second From Right.

A BRIGHT SHINING LIE John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. By Neil Sheehan. Illustrated. Random House.

Some wars are known for their heroes. Our parks are populated with statues of stalwart generals on rearing horses. But the war in Vietnam is known for its victims: the Americans who died and were maimed there for ”reasons of state” that few can now remember, the Vietnamese casually sacrificed by rival military machines. It is fitting that our monument to the dead of this war should be a slash in the earth with a roll call of the fallen.

But there were, of course, heroes in Vietnam, men who fought and died bravely and were loyal to their comrades; men who thought they were upholding an ideal, whether or not their leaders at home really believed in it. The effort to connect the struggle and sacrifice of these men with the politics of the war, the truth of the battlefield with the evasions and delusions of the policy makers, is the difficult work of literature.

Our war in Vietnam continues to haunt our consciousness. This is not only because of the 58,000 American lives lost, for both world wars took more. Nor is it because we were defeated, for most Americans eventually came to prefer even that to the endless bleeding for a cause their own leaders could not explain. Rather it is because Vietnam is the graveyard of an image we held of ourselves: America as the defender of the oppressed. In Vietnam we were confronted with ourselves as an imperial power, fighting not for democracy but to demonstrate that Communist-led ”wars of national liberation” were not the wave of the future.

Thus so much of the literature on Vietnam is one of disillusion: in the Vietnamese, in our leaders, in ourselves. ”A Bright Shining Lie,” as its very title suggests, is rooted in that disillusion. It vividly dramatizes and holds up to merciless scrutiny the Washington geopoliticians who ”wanted native regimes that would act as surrogates for American power,” a United States military leadership marked by ”professional arrogance, lack of imagination, and moral and intellectual insensitivity,” an American elite ”stupefied by too much money, too many material resources, too much power, and too much success” and an admired protagonist who turns out to be something other than he seemed.

As with most works of disillusion, the power of this compelling book lies in its anger. This anger infuses the extraordinary descriptive passages of battle, the machinations of confused or venal men in Washington and Saigon, and above all the account of the man who serves as both its hero and antihero. Immensely long, enormously ambitious, told with an emotion that bursts through its pages, this is an impressive achievement. If there is one book that captures the Vietnam War in the sheer Homeric scale of its passion and folly, this book is it.

Through the personality of John Paul Vann, a man of great courage and also of great cunning, Neil Sheehan orchestrates a great fugue evoking all the elements of the war: the conflict of wills and the self-deceiving illusions of the American military and civilian bureaucracy, the historical forces that brought the two sides into conflict; the terrible battles in which they sacrificed so many of their best; and the men who gave the struggle its meaning.

When a 26-year-old Sheehan first arrived in Saigon as a reporter in April 1962, there were only a dozen full-time resident correspondents and fewer than 5,000 United States military men in the country. At that time the war was still an adventure, and the Communist-led Vietcong seemed a nuisance that the Army of South Vietnam, with American guidance, could easily subdue. The Pentagon’s worst-case scenario called for victory by 1965 at the latest, with no more than 1,600 Americans still in the country. (By 1965 there would be almost 185,000, and by 1969 543,000.) But not all the American advisers to the South Vietnamese Army shared this optimism. Among the most outspoken of the skeptics was John Paul Vann, a lieutenant colonel who had served with distinction in the Korean War and arrived in Vietnam shortly before Mr. Sheehan.

Vann thought he had been sent to help a beleaguered democracy defend its freedoms. What he encountered was a South Vietnamese Army that would not fight, an officer corps mired in the corruption of Saigon politics, a military strategy based on the indiscriminate bombing and shelling of peasant hamlets and a feudal social system that surrendered the banner of reform to the Communists.

Vann was a dedicated and gung-ho officer. He had no quarrel with the war itself, any more than did the mostly young journalists who had been sent to report it. ”We regarded the conflict as our war too,” Mr. Sheehan says of himself and his colleagues. ”We believed in what our government said it was trying to accomplish in Vietnam, and we wanted our country to win this war just as passionately as Vann and his captains did.”

But it was a war that the Saigon Government was losing. A frustrated and angry Vann tried to tell his superiors that the attrition strategy was a failure, that the devastation of the countryside was winning converts to the Vietcong, that the South Vietnamese Army commanders cared more about pleasing their protectors in Saigon than in defeating the Communists, and the country’s leaders saw American involvement in their war as a way to line their pockets.

Unsurprisingly, few in Saigon were interested in what he had to say. With his pleas for a change in strategy ignored, Vann took a lesson from the Washington bureaucracy and began leaking information to the media. He formed a tacit alliance with the reporters, telling them the truth about the war in order to break through to the upper brass in Saigon and Washington. ”Vann taught us the most, and one can truly say that without him our reporting would not have been the same,” Mr. Sheehan writes. ”He gave us an expertise we lacked, a certitude that brought a qualitative change in what we wrote. . . . He transformed us into a band of reporters propounding the John Vann view of the war.”

Mr. Sheehan draws a compelling portrait of Vann, one that makes us feel his energy, commitment, idealism, bravery and charisma – all the things that made him a legend in Vietnam. For the reporters who gathered admiringly around him, and the younger officers who respected his courage in battle and his willingness to confront the generals in Saigon, he was a figure bigger than life, one whose ”moral heroism became the core of his legend.”

When the 39-year-old Vann left Vietnam in April 1963, his year’s tour of duty finished, a dedicated band of admirers came to see him off, ”proud for the man and what he had sought to achieve,” but sad because they were sure he would be punished for breaking the rules. For them he was ”the one authentic hero of this shameful period. . . . The David who had stood up to the Goliath of lies and institutional corruption.” Their fears for his future were confirmed when he resigned from the Army in July after the Pentagon seemed intent on punishing him for his assertiveness.

But Vann could not keep himself away from Vietnam. Two years later he returned, not as an officer, for the Army would not give him back his commission, but as a civilian pacification officer for the Agency for International Development. The very month of his return President Lyndon Johnson launched a major expansion of the war by bombing North Vietnam and sending United States Marines to defend the air base at Danang. As the Americans took over the war, in Saigon a succession of military officers curried favor with Washington and divided up the spoils brought by American largesse.

Vann had no illusions about the generals in Saigon, nor about the contempt in which they were held by the peasantry. ”If it were not for the fact that Vietnam is but a pawn in the larger East-West confrontation, and that our presence here is essential to deny the resources of this area to Communist China, then it would be damned hard to justify our support of the existing government,” he wrote an Army friend in 1965. ”. . . I am convinced that, even though the National Liberation Front is Communist-dominated, that the great majority of the people supporting it are doing so because it is their only hope to change and improve their living conditions and opportunities. If I were a lad of eighteen faced with the same choice – whether to support the GVN – Government of Vietnam – or the NLF – and a member of a rural community, I would surely choose the NLF.”

For Vann the problem was Saigon, not the war itself. With American casualties in Vietnam mounting, he thought that Washington could be forced to confront its mistakes by short-circuiting Saigon and sponsoring a social revolution that would win the peasants away from the Communists. ”What is desperately needed,” he wrote his friend Daniel Ellsberg in 1967, ”is a strong, dynamic, ruthless colonialist-type ambassador with the authority to relieve generals, mission chiefs and every other bastard who does not follow a stated, clear-cut policy which, in itself, at a minimum, involves the U.S. in the hiring and firing of Vietnamese leaders.”

But it was the American leaders who went first. In 1968 Gen. William Westmoreland, whose ”war of attrition” strategy was discredited by the Communists’ Tet offensive that winter, was relieved of command and sent home. Lyndon Johnson was also a victim of Tet, and announced that he would not run for re-election. Americans were beginning to look for a way out of Vietnam.

But for Vann the war had become an emotional commitment. In Mr. Sheehan’s words it ”satisfied him so completely that he could no longer look at it as something separate from himself.” The high number of casualties the Vietcong had paid for their psychological victory at Tet persuaded him that the war could still be won. The United States, he wrote President-elect Richard Nixon in 1968, ”could be eminently successful in South Vietnam at a cost of around five billion a year by 1975.”

Mr. Nixon’s policy of withdrawing American troops while stepping up the air war enhanced the importance of Vann’s pacification program. In 1971 he was made senior adviser for the Central Highlands, with authority over all United States military forces in the area. Although technically a civilian, he had the equivalent rank of a major general in the United States Army. His influence over the United States military-civilian mission and the Saigon Government made him ”the most important American in the country after the ambassador and the commanding general in Saigon.”

The Americans, having decided that Vietnam was not so crucial after all, would sign a peace treaty with Hanoi in 1973, and by 1975 the Communists would control the entire country. But for Vann the war ended on June 9, 1972, when his helicopter crashed and burned in a grove of trees. ”John Vann was not meant to flee to a ship at sea, and he did not miss his exit,” Mr. Sheehan tells us in a kind of epitaph. ”He died believing he had won his war.”

Vann was given a state funeral, posthumously awarded the nation’s highest civilian medal, and buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Among those who came to pay their respects were General Westmoreland, Mr. Ellsberg, Edward Lansdale, the C.I.A.’s roving honcho of counterrevolution who blocked the Vietcong from taking over South Vietnam in the 1950’s; Joseph Alsop, a pro-war columnist; William Colby, the C.I.A. director for covert operations; Robert Komer, the C.I.A. operative who orchestrated the Phoenix assassination squads; and Senator Edward Kennedy, one of the few legislators who shared Vann’s concern for refugees of the war.

What kind of man could bring together such disparate mourners: those who thought the war a noble cause, those who considered it politically disastrous or morally corrupting and those for whom it was just a job to be done? Clearly a man of many parts. Or perhaps one who was all things to all men.

Vann died a hero as he lived a hero, ”one of the authentic heroes of a grim and unpopular war,” in Mr. Komer’s salutation. But for Mr. Sheehan he was a hero with clay feet. Halfway through this very long book he confronts us with a person different from the exemplary figure to which we had been introduced. In a hundred-page section focusing on Vann’s origins and personal life, we discover a self-made man who could have stepped from the pages of a Dreiser novel: a man born into poverty and illegitimacy, a social climber, a dissimulator, an exploiter of women, an obsessive sexual athlete.

In Mr. Sheehan’s presentation this comes with the force of revelation. What he previously considered to be Vann’s moral heroism in risking his career to tell the truth, now seems to have been a cost-free gesture when he learns that Vann’s road to military promotion was probably blocked by one of his sexual indiscretions. Instead of unalloyed courage and integrity, he finds in Vann both ”a duality of personal compulsions and deceits that would not bear light and a professional honesty that was rigorous and incorruptible.”

Dramatically this is an effective device and makes the hitherto saintly Vann both more human and more interesting. It is presented in almost novelistic form, and reads as compellingly as any fiction. However, the reader may be somewhat less than shocked by Vann’s transgressions. It seems not so remarkable, nor so contemptible, after all, that a man who had surmounted a childhood of deprivation and cruelty by sheer force of will should be not only brave, resourceful and incorruptible, but also selfish and duplicitous.

What works well as a structural device – the good Vann and the bad Vann – is not developed psychologically. The fascinating and complex personality Mr. Sheehan has created defies such rigid categories. Rather than taking us inside Vann’s mind to make his motivation credible, Mr. Sheehan views him from too great a distance. Although Mr. Sheehan has graphically shown us the duality of Vann, he has not fully come to terms with it.

But the discovery of Vann’s other life provides the perfect counterpoint to the book’s theme of political deception. Just as Mr. Sheehan felt deceived by Vann, who had more complex motives than he revealed, so he had been deceived in once believing that America had gone selflessly to Vietnam ”to promote nationalism.” The truth he learned about the war was that ”the United States was a status quo power with a great capacity to rationalize arrangements that served its status quo interests.” The truth he learned about Vann was that in his personal life he would twist reality to suit his purposes. For him the admired Vann became, like the war itself, another ”bright shining lie.”

The parallel, if a bit forced, brings together what are really two books: a graphic history of the war and the story of John Paul Vann. They do not fully overlap, for at times Vann is the story, while at other times he fades away completely. This book is not so much a biography as it is a montage.

But a dazzling montage it is: vividly written and deeply felt, with a power that comes from long reflection and strong emotions. The dramatic scenes of lonely men locked in combat, the striking portraits of those who made and reported the conflict, the clash of wills and egos, the palpable touch and feel of the war, the sensitivity to the politics and psychology behind the battles, the creation of a memorable, though still mysterious, man – all these combine in a work that captures the Vietnam War like no other. Mr. Sheehan has created in John Paul Vann a man as complex and ambiguous as the war itself, a brave man of decent instincts in the grip of a compulsion that defied, and ultimately overwhelmed, reason.

THE HIDDEN SIDE OF A HERO

John Paul Vann’s funeral at Arlington National Cemetery in 1972 was the impetus that plunged Neil Sheehan into a 16-year ordeal of investigation and soul-searching that has finally brought forth his new book, ”A Bright Shining Lie.” In a telephone interview from his home in Washington, Mr. Sheehan described that funeral as a ”strange class reunion” at which ideological enemies joined under a flag of truce to mourn the man whose friends they had been.

Mr. Sheehan had been steeped in Vietnam from 1962 onward, when he first arrived in the country to cover the war for United Press International. Two years later he joined The New York Times, with assignments in Indonesia, Vietnam and Washington. In 1971, as an investigative reporter, he obtained the Pentagon Papers for The New York Times; for their publication the newspaper was awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

Mr. Sheehan had known Vann well in the early Vietnam years, and had often accompanied the flamboyant soldier in combat. But after the Arlington funeral he was to learn of another side of the celebrated hero from Vann’s former wife, Mary Jane.

”She agreed right away to talk to me about Vann’s past,” Mr. Sheehan said, ”and after I’d spent a couple of days interviewing her, I realized I had never really known the man.” Among the seamier episodes Mrs. Vann revealed was a charge of statutory rape the Army had brought against her husband. He eventually cleared himself, she said, by teaching himself how to fool the officials who administered his lie-detector test.

For Vann and many other Americans in and out of uniform, Vietnam provided a sorely needed righteous cause. But the war also held a visceral lure familiar to soldiers since the dawn of civilization. For some of those who went to Vietnam, muddy boots and M-16’s offered a liberating state of grace, in which the rules of behavior enforced back home were suspended, and in which a man could feel worthy even while burning villages and whoring around.

Mr. Sheehan, a former G.I. himself, learned that Vann, like any lesser mortal, had been driven by ambition, lust and rage as well as idealism. How did the discovery affect Mr. Sheehan’s personal feelings?

”After so many years as a reporter I became accustomed to suspending judgment,” he said. ”Even now, I have ambivalent feelings about Vann, but on the whole, I find him a sympathetic character. If our national leadership had listened to Vann, we might still be in Vietnam, for better or worse.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard