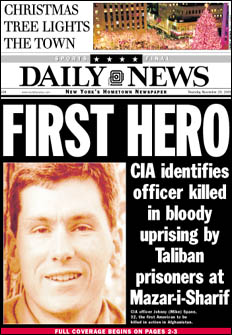

Central Intelligence Agency Officer

An American Hero

WINFIELD, Alabama — The CIA man was being brought to a funeral home near Arlington National Cemetery, so the distraught father shuttered his realty office in this three-stoplight town and flew up to the nation’s capital.

Running through his mind, he would say later, was Mike’s admonition, “Daddy, don’t ever believe I’m dead till you see my body.”

There in the casket lay Mike, and the father reached in and ran his hands across his son’s forehead. He remembered pulling up Mike’s head and peering at the back of his skull. He saw what appeared to be two exit wounds. He felt along his arms and legs and found bruising. It looked to him as if death came with a shot to each temple.

“I wanted to know: How did he die? Was he broken up? Was he tortured?” the father recalled.

More than three years have passed since Johnny “Mike” Spann, a CIA operative working in Afghanistan, became the first U.S. combat fatality in the war on terrorism. In that time, his father, Johnny Spann, a small-town real estate agent unversed in the ways of Washington and foreign intrigue, has undertaken an international odyssey to learn how his son died, to quell rumors and maybe to hold someone responsible for the death.

Mike Spann, a member of the CIA’s paramilitary Special Activities Division, was among those dispatched to Afghanistan in the weeks following the Sept. 11 attacks to track down Osama bin Laden. He was shot to death during an uprising by Taliban prisoners on Nov. 28, 2001, near Mazar-i-Sharif.

But the father needed to know more about what happened to his son that day. He has lobbied the Department of Justice, the Pentagon and the CIA. He has questioned Special Forces soldiers who were in Afghanistan when his son died. He has met with then-CIA Director George J. Tenet. And he has traveled to Afghanistan to interview some of the people who last saw his son alive.

At a campsite in the desert, the 56-year-old father broke bread with once-feared Afghan warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum, whose Northern Alliance soldiers worked with the CIA in the early days of the U.S. incursion into Afghanistan and were on the scene when the 32-year-old American was killed.

He persuaded Dostum to give him a videotape of the activity at the courtyard leading up to his son’s death. Securing the tape was a major victory for Johnny Spann, and it has spurred him to keep digging.

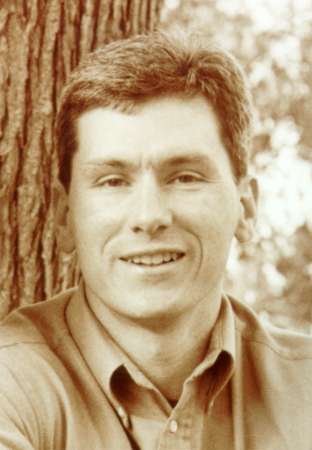

Three generations of Spanns have lived in Winfield, a town of about 4,700 northwest of Birmingham. Mike’s grandfather worked in the cotton mill, and his father was born here. Mike went to Winfield High, graduated from Auburn University and joined the Marines.

Today there is a memorial to Mike next to town hall. They named one of the main thoroughfares after him too. His father’s office is virtually a shrine to him, complete with his boyhood baseball cap, displayed on a shelf behind the desk. Someday the hat will be a gift for Mike’s son, now 3.

Mike is also known well beyond Winfield. For some, his standing as the first American to die in combat after the Sept. 11 attacks makes him a symbol of the struggle against terrorism.

In the courtyard where he died, the new Afghan government erected its own memorial to Mike.

Recently, his father received an e-mail from an American soldier who had visited the site.

“I felt a great admiration for this man I had never met,” wrote Army Staff Sgt. Jim McCool. “Even after having been there several times, I still get this feeling of great importance about this place. It’s like a ‘walking in the footsteps of a legend’ kind of a feeling.”

Mike’s father wants to preserve that image, even to the point where CIA and other government officials have cautioned him about becoming obsessed with how Mike met his end.

“I’ve been told that none of this matters any more,” Spann said. “I was told that things happened, and that Mike was dead now and that it didn’t matter any more. But everything matters to me.”

At home, he often plays the Dostum video on the living room TV, next to the U.S. flag that covered his son’s casket. He often slows and rewinds the tape at crucial scenes.

By the time terrorists hit New York and suburban Washington, Mike had already left the Marine Corps for the CIA. He was a father of three. Yet after the devastation at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, he volunteered to go to Afghanistan and search for Bin Laden.

“There was no way he wasn’t going to go,” his father said.

Accompanied by other CIA operatives and Special Forces soldiers, Mike joined with Northern Alliance troops in late November 2001 for their siege of Mazar-i-Sharif. Several hundred Taliban prisoners were taken and herded into the “Pink House,” a low-slung fort in nearby Qala-i-Jangi.

Among the prisoners, it was later learned, was John Walker Lindh, a young Northern California man who had traveled to the Middle East on a religious odyssey and ended up with the Taliban.

On Nov. 25, Mike went to the Pink House hoping to find captives with information about Bin Laden. Late that morning, the prisoners revolted.

It would be several days later that CIA officials visited Winfield to tell Spann that his son had been killed in the uprising while “fighting hand-to-hand.”

Mike’s death made headlines. His father remembers watching news video that showed Mike questioning a young American less than two hours before the uprising.

The man was soon identified as Lindh, who was dubbed the “American Talib” and taken into U.S. custody.

Almost immediately, Mike’s father suspected that Lindh had something to do with his son’s death.

Spann feared the CIA would never divulge the full story. He recalled Mike’s warning to believe nothing until “you see my body.” He pressed the CIA for the autopsy report, but it took a personal visit with Tenet to obtain a copy. He found the military doctor in Germany who had examined Mike’s body. He lobbied for photographs.

Other than confirming that the younger Spann suffered two gunshots to the head, the evidence was neither consistent nor conclusive. He could not tell whether Mike was shot from above or at close range.

He did not know whether Mike had been tortured or executed in cold blood, or neither or both.

He arranged a visit with Special Forces soldiers in Norfolk, Va., who told him Mike had gone down firing his AK-47, and when the rifle emptied, he turned his 9-millimeter pistol on the rioters rushing in and out of the Pink House.

As Spann conducted his investigation, Lindh was being prosecuted in the U.S. courthouse in Alexandria, Va. He was facing a possible life sentence for taking up arms with the Taliban. In Lindh, Spann found someone to hold responsible for his son’s death.

Spann theorized that the prisoner revolt was carefully planned and that Lindh was aware of it but failed to warn Mike, a fellow American.

Spann became a fixture at the courthouse, demanding justice. At one point, Lindh’s father, Frank, approached him at the close of a pretrial hearing and said something to the effect of “John had nothing to do with Mike’s death.”

Spann bristled and walked away.

“I should have taken out some of my revenge on him,” he recalled.

George C. Harris, one of Lindh’s attorneys, said Frank “was just trying to reach out his hand and be friendly.”

Then the two sides agreed to a 20-year plea deal for Lindh. Spann said he learned of it during a cellphone call in the drive-through lane at the McDonald’s in Winfield. He had to pull over to calm down.

Spann was convinced the Justice Department had caved in rather than allow U.S. intelligence officers or enemy combatants to testify at a trial, something they have blocked in numerous Sept. 11-related cases.

Federal prosecutors in the Lindh case denied such assertions, saying 20 years was an appropriate sentence.

At his sentencing, Lindh stated that he “had no role” in Mike’s death.

Spann spoke too, for about 18 minutes, telling the judge of the autopsy report and the trajectory of the bullets.

He suggested that Mike had been shoved to his knees and executed, close to where Lindh would have been.

In late 2002, several months after the case was settled, Spann attended the dedication of the Afghan government’s marble memorial to his son. While there, he interviewed two doctors who said they were standing with Mike when the riot broke out and that he had tried to fight back. Spann found a Northern Alliance soldier who said prisoners discussed what to do with Mike’s body and agreed that it meant a “sure trip to heaven” for whoever had killed him.

He met Dostum, now the Afghan government’s chief of staff for military affairs. The former warlord once allegedly sealed hundreds of Taliban captives in transport containers until they suffocated.

Over an evening meal of chicken and fruit at a campground, Spann said Dostum politely thanked him for Mike’s sacrifice. Spann, who had heard of a videotape of the events that day in the courtyard, said he asked Dostum about it.

The general initially denied it existed but eventually turned it over. For Spann, that was a breakthrough. The video, believed to have been recorded by a Northern Alliance commander, covered the two hours leading up to the riot.

Mike’s father, along with much of the nation, had seen some of the footage before, when a seven-minute version was aired on television.

In that portion, a handcuffed Lindh is escorted out of the house and onto his knees in the dirt courtyard and repeatedly refuses to respond to questions from Spann and another CIA operative, Dave Tyson.

Much of the rest of the tape shows several hundred cuffed prisoners being marched out of the Pink House and forced to sit on the ground in rows. Mike can be seen in the background, in blue jeans and a blue pullover sweater, an AK-47 slung over his back.

The tape convinced Spann that the prisoners plotted the uprising the night before. He believes they waited until half were out in the courtyard, giving them better position. He is certain that Lindh must have known what was about to happen.

But Harris, Lindh’s defense lawyer, denied that his client knew about the riot. He said it was hatched by a small group of Uzbek prisoners and that Lindh did not understand their language.

Harris also noted that Mike never identified himself to Lindh as a U.S. official, which appears to be true from the tape, and that Lindh assumed Mike was working with Dostum, which was correct because the U.S. was aligned with the Northern Alliance.

“That was John’s greatest fear, of being in Dostum’s custody and knowing how he treated prisoners,” Harris said. “Being in Dostum’s custody seemed to be sure death.”

The last two minutes of the tape show Mike behind the doctors, away from the Pink House. When the riot’s first grenade goes off, the tape abruptly stops. The video does not show what happened to Mike.

Harris said Lindh, hands still cuffed, was shot in the leg. Dozens of prisoners were killed, but about 80, including the wounded Lindh, returned to the Pink House for cover until they were routed by Dostum’s troops three days later. Lindh was turned over to U.S. forces.

Although the tape does not implicate Lindh in Mike’s death, it appears to counter recent allegations by Taliban soldiers now held at the U.S. prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, who claim that Mike sparked the riot when he killed one of the prisoners in the courtyard.

Those allegations are contained in FBI documents obtained through a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union of New York aimed at documenting prisoner abuse by the U.S. military.

Spann says the video shows the prisoners are lying, but he is not sure how much of the public believes him — especially in light of the outrage over prisoner torture and abuse in Afghanistan and Iraq.

So Johnny Spann continues his quest. He is working behind the scenes to quash an effort by the imprisoned Lindh for a presidential commutation of his sentence and says he is thinking of talking to Yaser Hamdi, another American citizen captured at the Pink House with Lindh.

Hamdi has since been returned to his family in Saudi Arabia, and Spann says he is looking into another trip to that part of the world.

CIA death in Afghanistan spurs dad’s quest

Johnny Spann, father of slain CIA officer Mike Spann of Alabama, who was the first American to die in Afghanistan, pauses at his son’s gravesite at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. in this February 28, 2005 file photo. There is no greater objective for the grieving father these days than gathering the facts behind the prison uprising in Afghanistan where his son became the first American casualty of the Afghan war

Johnny Spann stood in gently falling snow and wistfully recalled the day his son, CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, lingered among the tombstones at Arlington National Cemetery, studying each inscription and testing his sister Tanya’s patience.

“Mike, let’s go,” she implored. “They’re all the same.”

“No, Tanya, they’re not,” the younger Spann replied. “There are stories behind them.”

It is Mike Spann’s story that draws Johnny Spann to Arlington now.

There is no greater objective for the grieving father these days than gathering the facts behind the uprising on Nov. 25, 2001, at the makeshift prison in Afghanistan where his son became the first American casualty of the Afghan war.

Spann, a 56-year-old real estate company owner from Winfield, Alabama, visited Mike Spann’s grave last month for the third time in as many days. The elder Spann placed flowers and contemplated the chain of events that put his son in a national cemetery.

Upon returning to his rental car at the roadside, he wiped tears from his eyes.

“Even after four years, it doesn’t get any easier,” Spann said.

Articulate and folksy, with combed-back hair that is two shades of gray, Spann thumbs through a sheaf of documents and explains his son’s last living moments with methodical calm. It is the same trait he displayed daily at the trial of John Walker Lindh, the American fighting alongside the Taliban.

Spann is conducting his own investigation into the origins of the riot at the prison in Mazar-e-Sharif where suspected Taliban supporters were held.

U.S. government agencies, Spann said, are not inclined to piece together the entire story.

By investigating for himself, “No lies get told and nothing gets covered up,” he said in an interview. “I’ve got more at stake than they have. I want to know.”

During his visit to Washington, Spann shared with The Associated Press a videotape that shows the two hours leading up to the fateful riot.

Spann contends the last two minutes of footage prove the uprising began with a planned grenade attack inside the prison building rather than a spontaneous scuttle outside where his son was interviewing prisoners, including Lindh.

The distinction could be critical in Lindh’s quest to get clemency for his 20-year prison term. One of the most serious charges against Lindh was that the uprising was planned the night before, yet he did not warn Spann.

At one point, the younger Spann is seen with Lindh a short distance away from the other prisoners – a moment at which his father says Lindh had a chance to disclose the riot plot.

At trial, Lindh claimed no knowledge of the riot plot. The judge seemed to agree. If there were evidence that Lindh was responsible for the younger Spann’s death, the judge said, then a plea bargain would not have been accepted that spared Lindh more serious charges, such as murder or treason.

Spann’s father is convinced that such evidence exists. He refers to Lindh as “hard core al-Qaida” and says if Lindh really wanted to help a fellow American, he would have spoken up that morning.

Because he did not, Spann contends, Lindh was complicit in the younger Spann’s death. Some day, the father is hoping to prove this legally, in an attempt to get Lindh’s plea bargain thrown out.

“As soon as the grenade went off, they attacked Mike because that was their cue to do that,” Spann said. “It was a premeditated event.”

An intelligence official, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said the circumstances surrounding the incident at the prison were reviewed. The official said some prisoners burst out of the building firing weapons while Spann and a colleague were interviewing prisoners outside.

In the videotape, which Johnny Spann says he obtained from a Frenchman after the U.S. government initially denied him a copy, Mike Spann is last seen walking away from the prison building one minute before the uprising apparently began.

The next several seconds show a Taliban suspect being interviewed with his back to the building. There is a muffled noise and a series of screams. The suspect appears to twist his head to look over his left shoulder, toward the noise.

At that moment, the film cuts off. The videographer dropped the camera and ran, according to Spann.

In 2002, Spann went to Afghanistan to speak with some witnesses to the uprising. He talked to a Northern Alliance leader and two Afghan doctors who were treating Taliban soldiers.

Spann said the doctors told him that his son charged toward the prison building – right into a trap – when the grenade went off.

Later, Spann said, he reviewed autopsy reports that showed his son had two bullet wounds to the head. That indicates a method of death consistent with an execution-style slaying, Spann said.

“That doesn’t sound like two people in a fight getting shot,” Spann said. “That sounds like one guy is on his knees or something getting shot.”

Questions about the circumstances of the prison uprising surfaced in December with the disclosure of testimony by several Taliban prisoners who were at the Afghanistan prison on the day Spann died. They are now being held in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

One inmate acknowledged the explosion in the prison building but went on to suggest that a skirmish outside between Spann and a prisoner may have started the uprising. Spann “was jumped by an Arab or Pakistani male, but the armed man (Spann) shot the prisoner. People began running and chaos ensued,” according to the testimony, released by the American Civil Liberties Union as part of its investigation into alleged abuse of prisoners by American soldiers.

Spann does not dispute that his son probably killed some Taliban prisoners during a gunfight. But the father insists it was in self-defense and came after the grenade blast.

He also insists that the video proves there was no abuse of prisoners that day. The testimony from Guantanamo does not seem to imply there was, although one prisoner claimed he was threatened with a beating if he didn’t stay quiet.

“I wish Mike had been treated as well as they had been treated,” Spann said. “He’d probably be alive today.”

Spirit Fest helps Spann widow deal with loss of event honoree

The Fourth of July was Michael Spann’s favorite holiday long before that afternoon when Shannon Spann returned his smile.

But the CIA agent, who was killed in Afghanistan and will be honored at this year’s Spirit of America Festival, had to admit that the day he first celebrated America’s independence with Shannon stood above all others.

“He said that was the best Fourth of July he ever had,” Mrs. Spann said, recalling the time that she and her then-future husband truly began their relationship.

“That was before we started dating. Mike and I wound up at the same party on the Fourth of July. I don’t think he knew I was going to be there and I didn’t know he was going to be there.

“He was getting ready to leave just as I came, but then he stayed.” Other partygoers kidded them about how he suddenly changed his mind. “That was the first time we really talked and got to know each other.”

She said her husband would have loved to attend the Spirit of America Festival at Point Mallard Park that will honor him with the Barrett Shelton Freedom Award. But the CIA agent was killed Nov. 25, 2001, during a bloody prison uprising in northern Afghanistan at the hands of pro-Taliban fighters. Because the Fourth was Spann’s favorite holiday, Mrs. Spann, 32, said it will be difficult to celebrate without him, but getting to come to Decatur will ease the pain.

“We sure are blessed that there are Americans who take such care in setting up a celebration of that magnitude. Mike used to always say he didn’t think people did enough to take and mark days like Memorial Day and the Fourth of July,” she said.

The Freedom Award recognizes the outstanding achievements of Alabamians. Spann was a Winfield native and 1991 graduate of Auburn University before joining the Marines.

In 1999 he joined the Central Intelligence Agency, where he met Shannon. Both were training to become agents. She became a counter-terrorism officer. He served in the agency’s Special Activities Division, known as its paramilitary wing.

Similar to Jack Ryan

Spann’s CIA life was much like that of Jack Ryan from the Tom Clancy novels. Part intelligence operative, part combat trooper, he was among the first Americans to cross the border into Afghanistan after the Sept. 11 attack — even before military commandos began reconnaissance missions.

Spann was trained to supply and support local dissident groups and friendly governments. Officers like Spann can operate almost any kind of vehicle. They can infiltrate hostile countries and rescue U.S. officers or friendly foreign agents.

On the day he died, Spann was interrogating prisoners near Mazar-i-Sharif. The prisoners revolted and were able to seize rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. He was 32.

It didn’t take Spann long to impress his CIA directors while in training, Mrs. Spann said.

CIA Officer Killed in Afghanistan Buried

A CIA officer, who was the first known American combat death in Afghanistan was eulogized on Monday at a ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery as a hero who died serving his country “in the quest for right.”

Johnny Micheal Spann, known as “Mike,” was killed in a firefight at a fortress in northern Afghanistan on November 25 after pro-Taliban prisoners seized weapons from their Northern Alliance captors and sparked a bloody revolt.

Shannon Spann spoke at the service in section 34 of the cemetery where her husband’s grave will be marked by a simple white headstone similar to the rows around it.

She said her husband had always spoken from the heart and she would try to do the same, although hers had broken. “It broke when it fell to the ground two Sundays ago in a place really far from here,” she told the gathering of family, friends, and CIA colleagues.

“My husband is a hero, but Mike is a hero not because of the way that he died but rather because of the way that he lived,” she said. “Mike was prepared to give his life in Afghanistan because he already gave his life every day to us at home,” she said.

Spann, 32, a former Marine, received a full honors burial including a horse-drawn caisson that carried the flag-draped casket, three volleys of rifle shots by seven Marines, and a procession led by a Marine band and honor guard.

The covert CIA operative was a member of the paramilitary ”Special Activities Division,” the spy agency’s version of the military’s special forces units, and was involved in the interrogation of prisoners at the 19th century Qala-i-Jangi fortress near Mazar-i-Sharif when he died.

CIA Director George Tenet, at the ceremony, said Spann went to Afghanistan “in the quest for right.”

“To that place of danger and terror, he sought to bring justice and freedom,” Tenet said. “And to our nation — which he held so close to his heart — he sought to bring a still greater measure of strength and security,” he said.

Spann, in Afghanistan for about six weeks, was captured on videotape hours before he died at the fortress interviewing John Walker, an American fighting with the Taliban.

The videotape, first reported by Newsweek, showed Spann wearing blue jeans and a black sweater with a Kalashnikov rifle strapped across his back trying to get Walker to talk, but the prisoner stayed unresponsive.

“He served his country by being good. Not everyone is skilled or has the desire to go to faraway places to fight in wars but all of us have the skills and should have the desire to serve our country by being good,” Shannon Spann said.

“So we know that he was in the right place, at the right time and doing the right thing,” she said.

The United States has waged a war on terrorism since the September 11 attacks that killed thousands of people in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania. It has bombed Afghanistan since October 7 in retaliation to destroy Osama bin Laden and his al Qaeda network, who the United States blames for the attacks.

Shannon Spann told mourners about separate journals the couple had been writing while Spann was in Afghanistan and read an entry she made in October telling him he was her “favorite person” and she missed him. At the end of her remarks, she blew a kiss to her husband’s casket.

The Marines ceremonially folded the flag that covered Spann’s casket and handed it to her.

After most of the gathering had left, the family stayed for a private moment. Shannon Spann knelt by the casket, spoke a few words, and placed a kiss on it with her hand. Spann’s father carried the couple’s infant son to the casket, talking to the baby.

The CIA said it dispensed with its usual secrecy and publicly confirmed Spann’s death because it would not endanger covert operations and the media had already identified him.

Spann, who joined the CIA in June 1999, was expected to be memorialized with a star on the wall at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, that commemorates employees who died in the line of duty. The wall currently has 78 stars, 43 of which are publicly identified.

Spann is survived by his wife Shannon, an infant son, two daughters aged 4 and 9, two sisters, and parents Johnny and Gail Spann of Winfield, Alabama.

Remarks by the Director of Central Intelligence

George J. Tenet

Funeral of Johnny Micheal Spann

Arlington National Cemetery

Here today, in American soil, we lay to lasting rest an American hero. United in loss and in sorrow, we are united, as well, in our reverence for the timeless virtues upon which Mike Spann shaped his life—virtues for which he ultimately gave his life.

Dignity. Decency. Bravery. Liberty.

From his earliest days, Mike not only knew what was right, he worked to do what was right. At home and school in Alabama. As a United States Marine. As an officer of the Central Intelligence Agency. And as the head of his own, young family.

And it was in the quest for right that Mike at his country’s call went to Afghanistan. To that place of danger and terror, he sought to bring justice and freedom. And to our nation—which he held so close to his heart—he sought to bring a still greater measure of strength and security.

For Mike understood that it is not enough simply to dream of a better, safer world. He understood that it has to be built—with passion and dedication, in the face of obstacles, in the face of evil.

Those who took him from us will be neither deeply mourned nor long remembered. But Mike Spann will be forever part of the treasured legacy of free peoples everywhere—as we each owe him an immense, unpayable debt of honor and gratitude.

His example is our inspiration. His sacrifice is our strength.

For the men and women of the Central Intelligence Agency, he remains the rigorous and resolute colleague. The professional who took great pride in his difficult and demanding work. The patriot who knew that information saves lives, and that its collection is a risk worth taking.

May God bless Mike Spann—an American of courage— and may God bless those who love and miss him, and all who carry on the noble work that he began.

Slain CIA Officer Hailed As Hero

CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann was remembered as an American hero Monday as he was buried with full military honors amid the white grave markers of Arlington National Cemetery.

“From his earliest days … he worked to do what was right,” CIA Director George J. Tenet told those gathered, including many members of the CIA. “It was in the quest for right that Mike at his country’s call went to Afghanistan. To that place of danger and terror he sought to bring justice and freedom.”

The only American to die fighting enemies inside Afghanistan is “an American hero,” Tenet said.

Spann knew that “information saved lives, and that collection is a risk worth taking,” Tenet said.

Spann’s widow, Shannon, carried her infant son, wrapped in a white blanket against the chilly day, to the coffin, draped in an American flag. Spann’s two young daughters and other family members stood nearby.

Speaking after Tenet, she told the mourners her husband “served his country by being good.” She said her heart was broken two weeks ago “in a place really far from here.”

Spann, a paramilitary officer with the CIA’s Special Activities Division, was receiving full military honors from the Marine Corps, where he was a captain of artillery before joining the intelligence service 21/2 years ago.

He was shot and killed at the Taliban prison uprising at Mazar-e-Sharif on November 25 by rioting prisoners. He had been interviewing Taliban and al-Qaida fighters, including American John Walker, captured after their surrender in the nearby city of Kunduz, a former stronghold for the Islamic fundamentalists.

Tenet and other senior CIA officials attended Spann’s burial, along with many of Spann’s colleagues in the Directorate of Operations, the clandestine service. The agency allowed covert officers – who try to keep their identities secret – to decide whether to attend.

The CIA will hold a private service for him Tuesday, spokesman Mark Mansfield said. He described employees as saddened but resolute in the agency’s counterterrorism effort.

“The importance of the mission is what keeps people energized and focused,” Mansfield said.

The length of Spann’s military service did not qualify him for burial at Arlington. At his family’s request, President Bush signed a waiver allowing him to be buried there, a White House spokesman said. Of the 260,000 people buried at Arlington, only a few hundred were buried there after receiving a waiver.

A memorial service for him was held in his hometown of Winfield, Alabama, last week. Spann, 32, lived in a Virginia suburb of Washington.

A graduate of Auburn University, Winfield joined the CIA from the Marine Corps in June 1999.

Eight other Americans, all military personnel, have died in connection with the fighting in Afghanistan. Three Green Berets were killed by an errant U.S. bomb near Kandahar. Four U.S. personnel died in accidents; a fifth committed suicide.

The CIA is heavily involved in the Afghanistan conflict, working covertly alongside the more public military effort. CIA officers have been providing weapons, money and intelligence to rebel groups opposing the Taliban and al-Qaida, as well as interrogating prisoners captured during the fighting.

Spann is the 79th CIA employee to die in the line of duty. The first 78 have a star on the wall in the lobby of the agency’s main building in suburban Virginia. Spann’s will be added in the coming months.

Slightly more than half of the stars include names. The identities of the rest are kept secret. CIA officials said they had no compelling reason to keep Spann’s identity secret, and wanted to honor his sacrifice.

Two CIA officers died in the line of duty in 1998. No information has been released about their deaths. Some of the better-known include Robert Ames, who died in the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, and William Buckley, who was killed in 1985 after being kidnapped the previous year in Lebanon.

CIA’s Spann to be buried at Arlington

Johnny “Mike” Spann, the CIA agent from Alabama killed in Afghanistan, did not qualify for burial at Arlington National Cemetery but was granted a waiver after Senator Richard Shelby intervened.

Shelby, R-Ala., said he called the White House late last week when Spann’s family asked for help to have the Winfield native buried at Arlington. Shelby, ranking Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee, said Spann was “absolutely” worthy of the honor.

“Obviously, at the end of the day, the Department of Defense felt the same way,” Shelby said. “Not only did he die in service to his country, before then he had eight years with the U.S. Marines.”

Spann will be interred Monday with full military honors.

Veterans of the armed forces qualify for burial at Arlington, provided they are retired from active duty. Spann, 32, left the Marines in 1999 to join the CIA.

“Arlington is a very important place as a burial ground to honor our soldiers. But the land is scarce, and they have regulations. But there is also a provision for the Secretary of the Army to waive those regulations,” Shelby said.

The Director of Central Intelligence, George Tenet, also supported the

waiver, a spokesman said.

“There were many people who were very supportive of this,” spokesman Mark Mansfield said.

After hearing from Spann’s father, Johnny Spann of Winfield, Shelby called Nicholas Calio, the director of legislative affairs for the White House.

“I thought it was important to the Spann family that he be buried there and I was glad to do whatever I could do to accomplish that goal,” Shelby said.

Spann was the first American combat casualty in the war against terrorism. He was interviewing Taliban supporters held in a fortress near Mazir-e-Sharif and was killed November 25 when the prisoners rioted.

Also, the newly created CIA Officers Memorial Foundation plans to open the Mike Spann Fund to raise money for Spann’s survivors. He leaves a wife, Shannon, who also works at the CIA, and three young children.

Contributions can be made to The Mike Spann Fund, c/o Jeffrey H. Smith at Arnold & Porter, 555 12th Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20004.

Contributions are tax-exempt and tax-deductible. Jack Downing, former Deputy Director of Operations at the CIA, is a trustee.

President Bush had signed a waiver to have CIA paramilitary officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, the first U.S. combat death in Afghanistan, buried at Arlington.

The term of Spann’s service as a Marine Corps officer did not earn him a burial in Arlington, so his family asked the Bush administration for the waiver, a cemetery spokeswoman said.

Spann will be buried with full military honors on Monday. He was shot and killed by rioting Taliban prisoners on November 25 at Mazar-e-Sharif.

In Alabama, Family and Friends Mourn Agent Killed in Afghanistan Friday, December 7, 2001.

WINFIELD, Alabama, December 6 — Alison Spann, 9, a small girl with a brown ponytail and a red blouse, stood quietly beside her grandfather in the Winfield Church of Christ as he read the last letter she had written to her father, the one she wants placed in his casket.

“Dear Daddy, I will miss you dearly,” she wrote. “Thank you, Daddy, for making the world a better place.”

Here in this four-stoplight town of 4,500 people, hundreds came today to remember a hometown boy who is now being hailed as a national hero. Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, 32, a CIA intelligence officer who was the first American killed in the line of duty in Afghanistan, will be buried Monday in Arlington National Cemetery. But today was a time for those who knew him as a small boy at church, a high school football player who loved the fighter pilot movie “Top Gun,” and a gung-ho Marine Captain.

Spann’s former Sunday school teacher, Mildred McGuire, recalled how the youth “wanted to know everything about God.” His high school football coach, Joe Hubbert, told how, even as a teenager, he had his future precisely mapped out — first, a criminal justice degree from Auburn University, then a stint in the Marine Corps and finally, a career as a CIA or FBI agent.

“Most kids today don’t know who they are at that age or where they’re going, but Mike did,” Hubbert said.

Spann’s father, Johnny, a prominent real estate agent whose office is on the town’s main street, read aloud the last e-mail, dated September 19, he received from his oldest child and only son.

“What everyone needs to understand,” Mike Spann wrote, “is these fellows hate you — that’s right, they hate you, because you are an American.”

He went on to urge his family to write their congressmen to show their support for the war against terrorism. “Support your government and your military,” he wrote, “especially when the bodies start coming home.”

Spann, who had been in Afghanistan about six weeks, no longer qualifies as the only U.S. fatality in that faraway conflict; on Wednesday, the U.S. government announced the deaths of three American soldiers there from friendly fire.

Before last week, few people in Winfield, about 80 miles northwest of Birmingham, knew that Mike Spann worked for the CIA. They were aware only that he was employed by the federal government and lived in Manassas Park, Virginia, with his young family. And no one could have envisioned that, with his death during a prison uprising in Mazar-e Sharif, the streets of Winfield would suddenly be swarming with news reporters and satellite trucks.

“We have been unwittingly and somewhat unwillingly thrown under the national microscope,” James Wyers, the family minister, wrote in the program for today’s memorial service. “Not that any of our citizens are surprised that one of its own possessed the kind of ‘stuff’ that makes heroes. We believe in our town. And we believe our town is but an example of the real America that is out there.”

And so it was not only a deeply sad day for Winfield, but a proud one. American flags were interspersed among the Christmas street decorations; holiday lights in front of city hall spelled out “God Bless America.” Marquees in front of churches and small businesses summed up the town’s philosophy on the war: “Our prayers are with the Spann family,”

“One nation under God.”

Inside the Church of Christ, many among the more than 500 people present quietly wiped tears as they listened to the speakers, who sometimes fought hard to maintain their own composure.

Family friend Kelley Riley read several of the “thousands” of notes, cards and e-mails the Spann family has received in the past week, including one from Spann’s graduating class, the Winfield City High School class of ’87: “To our class, you will always be a hero,” it said. “Thanks, Mike.”

Spann had returned only occasionally to Winfield in the years since leaving for college, but townspeople here still recalled vividly the quiet youth with the distinctive smile who was a tough competitor on the playing fields and in the classroom.

Donations have poured in from here and around the country to the Mike Spann Memorial Fund at the local Citizens Bank, which will go to his three children — Alison, and Emily, 4, from his first marriage, and Jacob Micheal, six months, from his second marriage to wife Shannon, also a CIA employee.

It is a double tragedy for Spann’s daughters; their mother, Spann’s first wife, is suffering from cancer, family members said. But Spann’s father has stated publicly that his granddaughters will be well taken care of.

At the service, the tributes continued to be heard: Spann’s executive officer from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.; a military chaplain who was his boyhood friend; a representative from Governor Don Siegelman’s office. A Marine Corps color guard presented the flags and the congregation sang what were described as Spann’s two favorite hymns — “To Canaan’s Land” and “I’ll Fly Away.”

“We know from his quiet disposition that he wouldn’t want all this attention,” Pastor Wyers said. “But we also know he is an example for other young people.”

Arlington Burial for Afghanistan CIA Officer

A CIA Officer who was the first American combat death in Afghanistan will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery on Monday with full military honors, a CIA spokeswoman said on Wednesday.

Johnny Micheal Spann, a former Marine, was killed during a bloody prison uprising in northern Afghanistan last month in which pro-Taliban prisoners grabbed weapons from their Northern Alliance captors.

Spann, 32, was expected to be buried with full honors including a horse-drawn carriage to carry the casket, a 21-gun salute, and a Marine honor guard.

Spann died in a firefight that erupted when pro-Taliban fighters being held prisoner at the 19th century Qala-i-Jangi fortress near Mazar-i-Sharif seized rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers from their captors.

The CIA officer, who was part of the spy agency’s paramilitary “Special Activities Division,” was believed to have been involved in the interrogation of prisoners at the fort being conducted by the Northern Alliance.

Hundreds of pro-Taliban prisoners were killed during several days of U.S. airstrikes and Northern Alliance ground attacks that eventually quelled the revolt.

Somewhere between America’s spies and commandos is a small group of men and women like Johnny “Mike” Spann, the CIA paramilitary officer killed by rioting prisoners in Afghanistan.

Part intelligence operative, part combat trooper, these officers were among the first Americans to cross the border into Afghanistan after the September 11 – even before military commandos began reconnaissance missions.

“This is America’s secret warfare,” said Loch Johnson, a CIA expert at the University of Georgia, of the agency’s paramilitary force.

U.S. officials will not say how many are in Afghanistan and the surrounding countries, except that the contingent is much smaller than the hundreds of U.S. military special operations forces.

They are believed to be supplying weapons, training and intelligence to rebels fighting the Taliban. They are gathering information on their own, interrogating prisoners and defectors. Some are working alongside the Army’s Green Berets and other special operations forces, while others are on their own.

They come from within the CIA’s Directorate of Operations, whose primary mission is to conduct clandestine intelligence-gathering. This includes traditional case officers, who work out of U.S. embassies, trying to make sources out of foreign government officials.

One branch, the Special Activities Division, is home to the CIA’s offensive punch. Officers in this division are called upon when the president wants covertly to advance U.S. foreign policy, influencing a foreign government without any signs of U.S. action.

Inside the division are intelligence officers who can create economic and political disruptions in foreign countries. Others write propaganda to influence foreign elections.

The division also contains the Special Operations Group, which is the agency’s elite paramilitary cadre.

Similar to the Green Berets, these officers can train and supply local dissident groups and friendly governments. They are capable of more direct action, as well, including breaking into secure buildings to steal information.

Within this group are land, sea and air divisions, whose officers can operate almost any kind of vehicle. They can infiltrate hostile countries and rescue U.S. officers or friendly foreign agents.

“These intelligence officers relish the peril of unmarked air flights behind enemy lines and the command of speedboats in hostile waters,” wrote Johnson in “Bombs, Bugs, Drugs and Thugs,” a book published last year about the U.S. intelligence community.

They also provide combat training to regular CIA case officers.

Unlike the Green Berets, these officers can operate without uniform or identification as an officer of the U.S. government. If one is caught or killed, the government can plausibly deny their use. Unlike most military special operations forces, there are women among the CIA’s paramilitary ranks.

In recent decades, the paramilitary force has seen heavy use in Central America, Angola and Afghanistan. In Nicaragua, they mined the harbors and armed the Contra rebels during the Reagan administration. In Afghanistan, they helped the mujahedeen fight the Soviet invasion. During the Vietnam War, they ran “Air America” – the CIA’s covert effort in Laos.

In times of relative peace, the CIA’s paramilitary force is kept to a small cadre, but it can quickly surge during a conflict. To fill out the force’s ranks, the agency hires contractors – usually U.S. special operations forces troopers recently retired from the military. Active-duty commandos are also detailed to the agency.

Their use for offensive action requires a presidential “finding,” such as the wide-ranging finding signed by President Bush authorizing the CIA to make war on al-Qaida following the September 11 attacks.

Such findings lay out what activities are permitted, and senior congressional leaders must be informed of the covert action as well.

Spann, 32, joined the CIA about two years ago and was a paramilitary trooper. He was killed late last month by rioting prisoners at a compound in Mazar-e-Sharif in northern Afghanistan, the agency said. Spann was at the compound to interrogate prisoners.

His body was returned to the United States on Sunday.

PUBLIC ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF CIA OFFICER KILLED IN LINE OF DUTY

STATEMENT BY CIA SPOKESMAN BILL HARLOW

Several self-described experts have appeared on television recently criticizing the CIA’s decision to publicly identify Johnny Micheal Spann, the CIA officer who was killed in the line of duty in Afghanistan. These individuals have claimed that the decision was “unprecedented” and have even suggested that the Agency was exploiting Mr. Spann’s death in an effort to garner positive publicity. Nothing could be further from the truth. Such comments are irresponsible and do a great disservice to the Agency, the people who work for it, and Mr. Spann’s family.

We generally don’t respond to outrageous remarks made by uninformed critics. But these claims, which have been aired on several national television networks, are so reckless, malicious, and cynical that we believe it is necessary and appropriate to respond.

The protection of sources, methods, and the identities of officers serving under cover is essential to the Agency and we go to great lengths to preserve operational security.

Over the years, however, when circumstances permit, the CIA has publicly identified Agency officers who have been killed in the line of duty. There are currently 78 stars etched on CIA’s Memorial Wall for Agency employees who have died in the line of duty, and of those, fully 43 have been identified publicly and are included in CIA’s Book of Honor. Of those 43 brave Americans, more than 30 served in the Directorate of Operations, the Agency’s clandestine service. Among the heroes named in the Book of Honor are Richard Welch, the CIA official assassinated in Athens in 1975, and William F. Buckley, the Agency officer who was tortured and died in captivity in Beirut in 1985. When an officer under cover dies in the line of duty and there is no capability or reason to preserve their anonymity their names have been released.

As Director of Central Intelligence George J. Tenet has said, Johnny Micheal Spann was an American hero, a man who showed passion for his country and his Agency through his selfless courage. The circumstances surrounding his service at the CIA and his tragic death were such that his entire chain of command concurred that his name could be released without compromising security or any current intelligence activities. Moreover, the Spann family strongly supported the decision to publicly acknowledge Mike’s affiliation with the Agency and concurred with the text of our public announcement before it was released.

It also is worth noting that several media organizations published Mr. Spann’s name and affiliation with the Agency before his body had been recovered and death had been confirmed. Others had staked out the Spann family home prior to the Agency’s announcement, which was not made until after the body was recovered.

We may never be able to reveal the name of every CIA officer who dies in the line of duty. We will remain silent when we must but we will honor the names publicly when we can.

Johnny Micheal Spann was a true patriot whose heroic contributions to keeping America safe and free deserve the public’s recognition and gratitude.

(Note: “Micheal” is the correct spelling of Mr. Spann’s name)

CIA Operative Becomes First Combat Casualty

Johnny “Mike” Spann, a CIA paramilitary operations officer, was killed this week during a riot in a fortress in the Afghan city of Mazar-e Sharif where he was interviewing captured soldiers allied with the Taliban militia, the CIA announced today.

Spann, a former Marine captain, is the first American killed in action inside Afghanistan since the war on terrorism began and the 79th CIA officer to have died in the line of duty since the agency’s founding in 1947.

After extensive media speculation during the past three days that a CIA officer had been killed in the riot, CIA Director George J. Tenet confirmed Spann’s death in a closed-circuit television address this morning to all CIA employees and called Spann “an American hero, a man who showed passion for his country and his agency through his selfless courage.”

While many of the agency’s dead have never been publicly identified to protect the CIA’s sources and methods, Tenet decided that it was “fitting and appropriate” to identify Spann and honor his service, CIA spokesman Mark Mansfield said.

Tenet ordered the flag outside CIA headquarters to be flown at half mast and released a statement that outlined Spann’s career but provided only a brief description of the circumstances surrounding his death.

“Mike was in the fortress of Mazar-e Sharif, where Taliban prisoners werebeing held and questioned,” Tenet said in the statement. “Although these captives had given themselves up, their pledge of surrender – like so many other pledges from thevicious group they represent – proved worthless. Their prison uprising – which had murder as its goal – claimed many lives, among them that of a very brave American, whose body was recovered just hours ago.”

The riot erupted Sunday at the fortress outside Mazar-e Sharif, where hundreds of non-Afghan fighters allied with the Taliban from Pakistan, Chechnya and other Middle Eastern countries had been taken after surrendering at the northern city of Kunduz. Those fighters overpowered their captors from the Northern Alliance, stormed an armory and began fighting.

U.S. and British special forces helped put down the riot, calling in U.S. air strikes. But the fighting continued until early today. Five U.S. soldiers were seriously wounded Monday when a bomb dropped during one of those air strikes went astray. All five are now receiving medical care in Germany.

The New York Times reported today that Northern Alliance soldiers said that the riot erupted after Americans arrived and began interviewing the prisoners, who feared they were about to be executed. The Northern alliance troops said that one American intelligence officer was killed almost immediately on Sunday, The Times reported.

Spann, who lived in Manassas Park, Va., joined the CIA in 1999 after serving in the Marine Corps, Tenet said in his statement. Spann is survived by his wife, Shannon Spann, an infant son and two young daughters. He grew up in Winfield, Alabama, the son of Johnny and Gail Spann.

CIA Operative Dies in Prison Riot

CIA officer Johnny “Mike” Spann was killed in a prison riot at Mazar-e-Sharif in northern Afghanistan the CIA said Wednesday, the first American known to be killed in action inside the country since U.S. bombing began.

U.S. officials recovered his body Wednesday, several hours after northern alliance rebels backed by U.S. airstrikes and special forces quelled rioting by Taliban and al-Qaida prisoners.

The CIA provided no details on the circumstances of Spann’s death.

CIA Director George J. Tenet addressed agency employees Wednesday morning. He called Spann an American hero and said his fellow officers should “continue the mission that Mike Spann held” sacred.

“And so we will continue our battle against evil with renewed strength and spirit,” Tenet told colleagues, according to a CIA statement.

The flag outside CIA headquarters at McLean, Virginia, flew at half-staff.

Spann, 32, of Winfield, Alabama, joined the CIA in June 1999 and had served in the Marine Corps. He left behind a widow and three children.

Four Americans, all military personnel, have been killed in connection with the fighting in Afghanistan, but not in combat situations. All died in accidents outside the country. Two were killed in a helicopter crash in Pakistan. Eight journalists have also died.

The CIA has also been running covert operations in Afghanistan alongside the more public military effort in the 7-week-old war. CIA officers are believed to have been providing weapons, money and intelligence to rebel groups opposing the Taliban and al-Qaida, as well as interrogating prisoners captured during the fighting.

The riot at the prison began Sunday when hundreds of Pakistanis, Chechens, Arabs and other non-Afghans, who had fought with the Taliban, were brought to the fortress after the weekend surrender of Kunduz, the Islamic militia’s last stronghold in the north.

Once inside, the men broke loose, stormed the armory and rose up against their alliance captors.

Spann was in the complex where Taliban prisoners were being held and questioned, the CIA said.

Hundreds of inmates held out for days, despite U.S. bombing and assault by thousands of alliance fighters. U.S. special forces and other troops, believed to be British, took part in the battle and coordinated airstrikes.

Five U.S. soldiers were seriously wounded Monday when a U.S. bomb went astray, exploding near the Americans. They were evacuated to a U.S. military hospital in Germany.

The alliance recaptured most of the prison by Tuesday, but a last few fighters were holding out in the deepest recesses of the prison. Hundreds of prisoners and dozens of alliance fighters were believed dead.

Two CIA officers died in the line of duty in 1998, previously the most recent deaths of agency employees. No information has been released about their identities or the circumstances of their deaths.

Since the agency’s creation, 78 CIA officers and employees have died or been killed in the line, agency spokesman Mark Mansfield said. Each has a star on the wall in the lobby of the agency’s main building.

Slightly more than half of the stars have a name tied to them. The identities of the rest are kept secret.

The most recent acknowledged death was that of analyst John Celli, who died in a car accident while working in the Middle East in November 1996.

Some of the better-known include Robert Ames, who died in the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, and William F. Buckley, who was tortured and killed by Hezbollah in 1985 in Lebanon.

Two employees, Lansing Bennett and Frank Darling, were shot and killed outside agency headquarters by a Pakistani who claimed the shootings were his “moral duty.”

WINFIELD, Alabama – Johnny “Mike” Spann craved the anonymous grunt work no one else wanted – covertly serving his country far away from this sleepy town that he once called home.

Spann was fulfilling his duties as a CIA officer when he was killed in Afghanistan, becoming the first American known to die in combat there.

“He gave his life in the line of work – in the line of duty,” Spann’s father, Johnny Spann, said Wednesday after the CIA confirmed his son’s death. He said Osama bin Laden was to blame.

Rioting prisoners killed Mike Spann at a compound in Mazar-e-Sharif in northern Afghanistan, the aency said. Officials recovered his body from the prison after northern alliance rebels backed by U.S. airstrikes and special forces quelled an uprising by Taliban and al-Qaida prisoners.

The riot began Sunday when hundreds of prisoners stormed an armory for weapons. By the time the fortress was recaptured on Wednesday, hundreds of prisoners and dozens of alliance fighters were dead.

In his hometown of Winfield, in northwestern Alabama, Spann was remembered by friends and relatives as a goal-oriented ex-Marine who always wanted to do the right thing without drawing attention to himself.

His father said it was those traits that made him a natural for the CIA, where Spann had wanted to work since he was a teen-ager.

Spann joined the CIA about two years ago. He was a paramilitary trooper in the agency’s commando arm, which is equipped to arm and train local forces and to conduct covert assaults.

When Spann joined the CIA he told his family, “Someone has got to do the things no one else wants to do,” his father recalled.

“That is exactly what he was doing in Afghanistan,” his father said.

Spann, who lived in Virginia, was survived by a wife and three children, aged 4, 9 and 6 months. His father said he had been in Afghanistan for about six weeks.

In Washington, Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama said he had spoken to

Spann’s widow, Shannon.

“She said that when I saw people, I should tell them her husband cared about America, cared about the future of America and cared about the security of Americans,” said Shelby, fighting back tears.

President Bush said through a spokesman that he regretted Spann’s death.

“The president understands that this battle began September 11,” White House press secretary Ari Fleischer said. “There may be more injuries, there may be more deaths, and the president regrets each and every one.”

Spann graduated in 1987 from Winfield City High School, where he played football. He earned a degree in criminal justice and law enforcement at Auburn University.

Like many in this sleepy town of about 4,500, Spann set his sights on something bigger. After serving with the Marines, he earned a post in America’s foreign intelligence agency.

Danny Little, an insurance agent who watched Spann grow up, said he was proud to have been acquainted with a man who gave his life helping others.

“Lord knows how many people will benefit, because those people he was fighting are evil,” he said.

The CIA has been conducting covert operations in Afghanistan alongside the more public military effort. CIA officers are believed to have been providing weapons, money and intelligence to rebel groups opposing the Taliban and al-Qaida.

CIA officers also interrogated captured prisoners – the very duty that brought Spann to the prison where he was killed.

Four other Americans other than Spann, all military personnel, have been killed in connection with the fighting in Afghanistan. All died in accidents outside the country.

Spann was the 79th CIA employee to have died in the line of duty.

Major Mike Mullins, who was Spann’s commanding officer on Okinawa from 1994 to 1995, said he wasn’t surprised that Spann found himself in the middle of a fight.

“He was very serious – and his main concern was that his Marines were prepared to go to battle,” said Mullins, now at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. “That’s the kind of guy he was. He told you straight and stuck to it. He was focused on the mission.”

CIA HERO’S BODY RETURNS TODAY

December 2, 2001 — The remains of the heroic CIA agent killed during bloody riots with Taliban prisoners returns home from Afghanistan today, a day after four soldiers wounded during the uprising were honored with Purple Hearts.

The body of Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, the first American to die in action in Afghanistan, will be brought to Andrews Air Force Base, where CIA chief George Tenet will join the slain man’s family to honor him.

Spann, whose wife gave birth to a boy just six months ago, will become the 79th star in the lobby of the CIA building to hail the memory of agents who died in the line of duty, although officials said that could take a few months.

His name will be written next to the star. Forty-three stars have names, while the others remain clandestine even in death.

The 32-year-old Spann was killed by al Qaeda thugs during prison riots outside Mazar-e-Sharif.

The horrible discovery came three days after 500 prisoners of war seized the Qalai Janghi complex. The riots were quelled by Northern Alliance forces, along with commando raids and U.S. airstrikes.

Spann’s funeral arrangements are pending.

Yesterday, four U.S. soldiers were awarded Purple Heart medals for injuries they sustained during the uprising.

During the ceremony at a U.S. military hospital in Germany, Major General Geoffrey C. Lambert said the four GIs “have given their blood fighting in the war against terrorism.”

“We’ll do everything we can to stamp it out,” he pledged, as about 20 people, including a handful of the soldiers’ relatives, looked on.

The four men were wounded by a stray missile while advising alliance fighters trying to put down the riots.

The coffin containing the body of CIA agent Johnny “Mike” Spann is carried at Andrews Air Force

Base outside of Washington D.C. Devember 2, 2001. Spann, the first American

to die in combat in Afghanistan, was killed in a prison uprising by captured Taliban militiamen.

The body of CIA officer Johnny Mike Spann is carried by a Marine honor guard

from an Air Force aircraft December 2, 2001 at Andrews Air Force Base.

Shannon Spann, right, carrying her infant son Jake, is escorted by Brigaider General

Glenn Spears as the coffin containing the body of CIA agent Johnny “Mike” Spann

is carried at Andrews Air Force Base outside of Washington Sunday, Dec. 2, 2001.

CIA Director George J. Tenet (L) pats Jake Spann, infant son of CIA Officer Johnny Mike Spann, at Andrews Air Force

Base, December 2, 2001. Spann was the first known American combat death in the U.S. military campaign in Afghanistan,

which is aimed at destroying Osama bin Laden, his al Qaeda network and the Afghan Taliban movement, which sheltered him.

Johnny Spann, father of CIA Officer Johnny Mike Spann, holds hands with his wife Gail, (R) and daughter Tonya Ingram (L)

after viewing his son’s casket aboard an Air Force aircraft, December 2, 2001 at Andrews Air Force Base.

Alison Spann, the daughter of CIA Officer Johnny Micheal Spann is comforted by Stephanie Glakas Tenet,

wife of CIA director George J. Tenet, as the remains of CIA officer Spann, killed during a prison uprising in

northern Afghanistan, returned to Andrews Air Force Base, December 2, 2001.

CIA Director George J. Tenet embraces Shannon Spann, the widow of CIA Officer Johnny Mike Spann, at Andrews Air Force Base, December 2, 2001.

Shannon Spann, wife of CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, follows her husband’s casket to the grave side as she

holds her 6-month old son Jake, at his funeral in Arlington National Cemetery, Monday, December 10, 2001

Shannon Spann, wife of CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, holds her son Jake, 6 months old, at the graveside of her

husband’s funeral at Arlington National Cemetery, Monday, December 10, 2001. With her from left in the front

row are CIA Director George Tennet and his wife Stephanie Glakas-Tennet, Johnny and Gail Spann, father and mother

of Mike Spann, Shannon Spann and Micheal’s sister Tonya Ingram. They are watching the casket as it is moved to the grave.

The casket of Johnny Micheal Spann, the CIA officer killed during a violent prison uprising in Afghanistan, is carried by an

honor guard of U.S. Marines during a funeral ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, December 10, 2001.

The flag-drapped casket of Johnny Micheal Spann, the CIA officer killed during a violent prison uprising in

Afghanistan, is carried by an honor guard of U.S.Marines during a funeral ceremony at Arlington

National Cemetery, December 10, 2001.

Shannon Spann, seated left, wife of CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, and Spann’s mother Gail Spann, seated right,

watch the folding of the flag that covered his casket as he was honored at a burial ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, Monday, December 10, 2001 in Arlington, Virginia.

Shannon Spann, wife of CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, stands beside her husband’s

casket as he was honored at a burial ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, Monday, December

10, 2001 in Arlington, Virginia. Seated right is his sister, Tammy Spann, holding Micheal’s daughter, Emily Spann.

Shannon Spann, widow of Johnny Micheal Spann, the CIA officer killed during a violent prison uprising

in Afghanistan, attends his funeral ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, December 10, 2001

Shannon Spann, wife of CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, stands by her husband’s coffin as the honor

guard folds the flag that covered his casket as he was honored at a burial ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery,

Monday, December 10, 2001 in Arlington, Virginia. Spann was remembered as an American hero as he was buried with full military honors.

CIA Director George Tennet wipes his eye and stands beside his wife Stephanie Glakas-Tennet as Shannon Spann

gives her graveside remarks at the funeral for her husband CIA officer Johnny Micheal “Mike” Spann, at Arlington National

Cemetery, Monday, December 10, 2001 in Arlington, Virginia.

Shannon Spann, wife of CIA officer Johnny “Mike” Spann, sits beside his grave at Arlington National

Cemetery on Memorial Day, Monday, May 27, 2002

Shannon Spann, widow of CIA officer Johnny “Mike” Spann, and her three children,

from left, Emily, 4, Alison, 10, and Jake, 11 months, visit her husband’s

grave at Arlington National Cemetery on Memorial Day, Monday, May 27, 2002

Shannon Spann, widow of Johnny ‘Mike’ Spann, the CIA officer who was the first American killed by the enemy in the war on

terrorism in Afghanistan, and their son Jacob pause at a marker after a wreath-laying ceremony at

Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, Monday, October 7, 2002, to remember those

who died in Operation Enduring Freedom in the year since the war in Afghanistan began.

SPANN, JOHNNY MICHEAL

CAPT US MARINE CORPS

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 06/26/1993 – 06/26/1999

- DATE OF BIRTH: 03/01/1969

- DATE OF DEATH: 11/25/2001

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 12/10/2001

- BURIED AT: SECTION 34 SITE 2359

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard