Another of my personal heroes

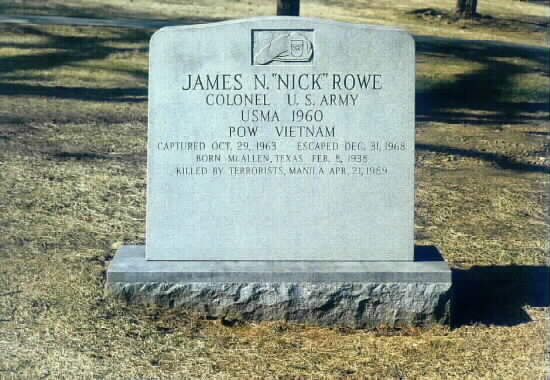

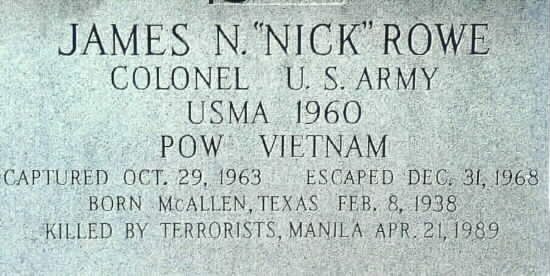

Colonel “Nick” Rowe graduated from West Point in 1960 and made the Army his career. When his country became engaged in Vietnam, he served there as a Special Forces Officer (Green Beret) and was captured by enemy forces on October 29, 1963. He struggled against the depravity of the prison camps, never giving up hope, until finally on December 31, 1968 he escaped his captors and made his way back to allied lines.

Sadly, he was killed by Communist guerrilas in Manila, Philippines, on April 21, 1989 and was buried in Section 48 of Arlington National Cemetery.

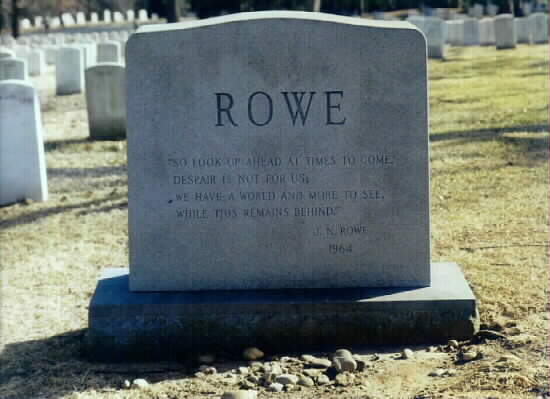

He had once written, “So look up ahead at times to come, despair is not for us. We have a world and more to see, while this remains behind.” This is enscribed on his gravestone and is a fitting memorial for yet another American Hero who left us entirely too soon.

From a contemporary press report:

Sunday, April 23, 1989 McALLEN, Texas – The Viet CONG kept James N. ”Nick” Rowe in a bamboo cage in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta for five years, but they couldn’t break his spirit with a constant barrage of propaganda and daily death threats.

Instead, hooded gunmen in the Philippines took the life of the 51-year-old Army colonel. Rowe was shot to death Friday as he drove to work at the Joint U.S. Military Advisory Group headquarters outside Manila.

In the fall of 1963, Rowe, then a first lieutenant in the Special Forces serving as an adviser to South Vietnamese irregulars, was captured by Viet Cong guerrillas in the Mekong River delta.

He was held in jungle camps, from which he tried repeatedly to escape. Word reached U.S. intelligence officers that he was known to his captors as ”Mr. Trouble.”

For much of his captivity, he was held in a bamboo cage and allowed to venture only 40 yards during the day.

He busied himself chopping firewood and setting traps to capture small animals to supplement his diet of rice and fish.

Rowe finally escaped from his cage on New Year’s Eve, 1968 – and was nearly killed by U.S. forces who thought the black-pajama-clad Special Forces officer was a Viet Cong. He had sighted a U.S. Cobra helicopter and ran into a clearing, signaling for help.

The first impulse of the men in the helicopter was to shoot the man, because he was dressed like the Viet Cong. But Army Major Dave Thompson ordered the men to hold their fire because he wanted to take him prisoner.

Rowe was only one of 34 Americans who escaped captivity during the Vietnam War.

He came home to McAllen to a hero’s welcome. He had graduated from West Point in 1960.

In his book, ”Five Years To Freedom,” Rowe describes approaching McAllen in a helicopter. ”I was totally absorbed with my thoughts as I watched the towns pass below, bringing me miles closer to my home; it had been such a long, long journey both in time and space.”

At his parents’ home, the young officer dashed from the car to the front porch, where his father, Lee Rowe, opened the door. ”Dad, dad, I’m sorry I didn’t get home sooner; they just wouldn’t let me go.” He hugged his mother, Florence.

James Rowe recalled: ”The three of us stood for a long moment, touching, communicating without speaking. My world was complete; I had reached out and touched the light.”

A few weeks later, Rowe made a speech at McAllen High School’s football stadium, and a parade was held. Thousands turned out for a glimpse of the hometown hero.

His father died in 1973, his mother in 1982. Rowe left the Army in 1976 but returned to the Special Forces as a lieutenant colonel in 1981 to become chief of a Green Beret training program at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

In 1985, Rowe was placed in command of the First Special Warfare Training Battalion at Fort Bragg. He held that post until last May, when he went to the Philippines.

John Ford, one of Rowe’s cousins, remembered him as a brave man who knew what he was getting into when he was sent to the Philippines. Ford said Friday: ”He knew it was a hot spot when he went over there. He knew he had to be careful. He walked like an Army officer, he talked like one and he died like one.”

In Washington, Army Chief of Staff General Carl Vuono, a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called Rowe ”a personal friend, a selfless and faithful soldier who served his country in accordance with the finest traditions of the American Army.”

”All of us who are left behind must take stock in the courageous and determined examp le of service that Nick has given us and redouble our efforts to protect democracy and freedom at home and around the globe.”

Rowe’s second wife, Mary, and their two sons, Stephen and Brian, live in Manila. Two daughters by a previous marriage, Deborah and Christina, live in Middleburg, Virginia.

His body will be returned to the United States early this week for burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Name: James Nicholas “Nick” Rowe

Rank/Branch: O2/US Army Special Forces

Unit: Detachment A-23, 5th Special Forces Group

Home City of Record: McAllen TX (res. Potomac Maryland in 1973)

Loss Date: 29 October 1963

Country of Loss: South Vietnam

Loss Coordinates: 092626N 1050917E (WR170435)

Status (in 1973): Escaped POW

Category: Acft/Vehicle/Ground: Ground

Other Personnel in Incident: Humberto R. Versace (missing); Daniel L. Pitzer

(released 1967); At Hiep Hoa: Claude D. McClure; George E. Smith (released

1965); Issac Camacho (escaped 1965); Kenneth M. Roraback (missing).

Source: Compiled by HOMECOMING II from one or more of the following: raw

data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA

families, published sources, interviews. Updated by the P.O.W. NETWORK May

1997.

REMARKS: 681231 ESCAPED

SYNOPSIS:

The U.S. Army Special Forces, Vietnam (Provisional) was formed at Saigon in 1962 to advise and assist the South Vietnamese government in the organization, training, equipping and employment of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) forces. Total personnel strength in 1963 was 674, all but 98 of whom were TDY from 1st Special Forces Group on Okinawa and 5th and 7th Special Forces Groups at Ft. Bragg. USSF Provisonal was given complete charge of the CIDG program, formerly handled by the CIA, on July 1, 1963.

The USSF Provisional/CIDG network consisted of fortified, strategically located camps, each one with an airstrip. The area development programs soon evolved into combat operations, and by the end of October 1963, the network also had responsibility for border surveillance. Two of the Provisional/CIDG camps were at Hiep Hoa (Detachment A-21) and Tan Phu (Detachment A-23), Republic of Vietnam. Their isolated locations, in the midst of known heavy enemy presence, made the camps vulnerable to attack.

On October 29, 1963, Captain “Rocky” Versace, First Lieutenant “Nick” Rowe, and Sergeant Daniel Pitzer were accompanying a CIDG company on an operation along a canal. The team left the camp at Tan Phu for the village of Le Coeur to roust a small enemy unit that was establishing a command post there. When they reached the village, they found the enemy gone, and pursued them, falling into an ambush at about 1000 hours. The fighting continued until 1800 hours, when reinforcements were sent in to relieve the company. During the fight, Versace, Pitzer and Rowe were all captured. The three captives were photographed together in a staged setting in the U Minh forest in their early days of captivity.

The camp at Hiep Hoa was located in the Plain of Reeds between Saigon and the Cambodian border. In late October 1963, several Viet Cong surrendered at the camp, claiming they wished to defect. Nearly a month later, on November 24, Hiep Hoa was overrun by an estimated 400-500 Viet Cong just after midnight. Viet Cong sympathizers in the camp had killed the guards and manned a machine gun position at the beginning of the attack. The Viet Cong climbed the camp walls and shouted in Vietnamese, “Don’t shoot! All we want is the Americans and the weapons!” Lieutenant John Colbe, the executive officer, evaded capture. Captain Doug Horne, the Detachment commander, had left earlier with a 36 man Special Forces/CIDG force. The Viet Cong captured four of the Americans there. It was the first Special Forces camp to be overrun in the Vietnam War.

Those captured at Hiep Hoa were Sergeant First Class Issac “Ike” Camacho, SFC Kenneth M. Roraback (the radio operator), Sergeant George E. “Smitty” Smith and Specialist 5th Class Claude D. McClure. Their early days of captivity were spent in the Plain of Reeds, southwest of Hiep Hoa, and they were later held in the U Minh forest.

“Ike” Camacho continually looked for a way to escape. In July 1965, he was successful. His and Smith’s chains had been removed for use on two new American prisoners, and in the cover of a violent night storm, Camacho escaped and made

his way to the village of Minh Thanh. He was the first American serviceman to escape from the Viet Cong in the Second Indochina War. McClure and Smith were released from Cambodia in November 1965.

Rocky Versace had been torn between the Army and the priesthood. When he won an appointment to West Point, he decided God wanted him to be a soldier. He was to enter Maryknoll (an order of Missionaries), as a candidate for the priesthood, when he left Vietnam. It was evident from the beginning that Versace, who spoke fluent French and Vietnamese, was going to be a problem for the Viet Cong. Although Versace was known to love the Vietnamese people, he could not accept the Viet Cong philosophy of revolution, and spent long hours assailing their viewpoints. His captors eventually isolated him to attempt to break him.

Rowe and Pitzer saw Rocky at interludes during their first months of captivity, and saw that he had not broken. Indeed, although he became very thin, he still attempted to escape. By January 1965, Versace’s steel-grey hair had turned

completely white. He was an inspiration to them both. Rowe wrote:

..The Alien force, applied with hate,

could not break him, failed to bend him;

Though solitary imprisonment gave him no friends,

he drew upon his inner self to create a force so strong

that those who sought to destroy his will, met an army his to command..

On Sunday, September 26, 1965, “Liberation Radio” announced the execution of Rocky Versace and Kenneth Roraback in retaliation for the deaths of 3 terrorists in Da Nang. A later news article stated that the executions were faked, but the Army did not reopen an investigaton. In the late 1970’s information regarding this “execution” became classified, and is no longer part of public record.

Sergeant Pitzer was released from Cambodia November 11, 1967.

First Lieutenant Nick Rowe was scheduled to be executed in late December 1968. His captors had had enough of him – his refusal to accept the communist ideology and his continued escape attempts. While away from the camp in the U Minh forest, Rowe took advantage of a sudden flight of American helicopters, struck down his guards, and ran into a clearing where the helicopters noticed him and rescued him, still clad in black prisoner pajamas. He had been promoted to Major during his five years of captivity.

Rowe remained in the Army, and shared his survival techniques in Special Forces classes. In 1987, Lieutenant Colonel Rowe was assigned to the Philippines, where he assisted in training anti-communists. On April 21, 1989, a machine gun sniper attacked Rowe in his car, killing him instantly.

Of the seven U.S. Army Special Forces personnel captured at Hiep Hoa and Tan Phu, the fates of only Versace and Roraback remain unknown. The execution was never fully documented; it is not known with certainty that these two men died. Although the Vietnamese claim credit for their deaths, they did not return their remains. From the accounts of those who knew them, if these men were not executed, they are still fighting for their country.

NICK ROWE: U.S. KNEW INDEPENDENTLY OF THREAT TO HIS LIFE

INTELLIGENCE WAS NEVER PASSED ON

Special to the U.S. Veteran

by James Neilson

In the Fall prior to Colonel Nick Rowe having been gunned down on April 21, 1989 by members of the communist New Peoples’ Army (NPA) in the Philippines, the U.S. State Department’s Intelligence and Research Bureau had assimilated reliable information on the Communist Party’s intensified efforts to ferret out and execute “deep penetration agents” working for the CIA inside the Philippines’ communist organization, U.S. Veteran News and Report has learned.

The seriousness of this threat contrasted significantly with the State Department’s having ignored Rowe’s own warnings that the NPA, the Philippine equivalent of the Vietcong, was planning major terrorist acts against U.S. military advisors.

A highly decorated Green Beret and Vietnam veteran who survived five years of captivity in a Viet Cong prison camp, Rowe was chief of the army division of the Joint U.S. Military Advisory Group (JUSMAG) providing counter-insurgency training for the Philippine military. In this capacity, he worked closely with the CIA, and was involved in its nearly decade-old program to penetrate the NPA and its parent communist party in conjunction with Philippine’s own intelligence organizations.

Rowe was killed instantly by one of a volley of bullets that were fired from an M-16 and a .45-caliber pistol from the hooded NPA occupants of a small white car that had pulled alongside Rowe’s unarmored chauffeur-driven limousine in the Manila suburb of Quezon City.

By the time Rowe was killed, however, the State Department had known for months about the Philippine Communist Party’s efforts to identify CIA-backed agents which had been infiltrated into the party’s ranks since the early 1980’s. The State Department also knew that “a number” of these agents had already been captured, interrogated and executed. For almost a year prior to Rowe’s assassination by the NPA, the State Department had been monitoring the communist’s counter- intelligence efforts, and knew that the CIA’s assets in the party were in jeopardy as a result.

By February, 1989, Rowe had developed his own intelligence information which indicated that the communist were planning a major terrorist act. As a result of the intelligence and his analysis of the situation in the Philippines, Rowe wrote Washington warning that a high-profile figure was about to be hit and that he, himself, was No.2 or No.3 on the terrorist list.

The State Department ignored Rowe’s letter and apparently never warned him about the seriousness of the threat. Intelligence sources say Rowe was a “classic expendable;” that he was not warned because he likely would have tried to safely get out any agents he personally knew of inside the NPA or communist party.

“Undoubtedly there were some who didn’t want to loose those assets,” an intelligence source said.

One reason such assets may have been deemed important enough not to alert Rowe to the threat was that the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) was receiving information on possible growing Cuban involvement with the NPA.

Six months before Rowe’s murder, the DIA had learned that Cuban advisors appeared to be assisting the NPA in the South-Central Luzon province, one of the two provinces where the NPA was focusing on ferreting out CIA agents within its ranks.

Neither the DIA or the State Department would comment on any of the intelligence it has collected on the NPA or Communist Party. Although Rowe was a visible military official and certainly a target for the communist terrorists, some intelligence sources believe his assassination resulted from his having been fingered as a possible control officer or trainer of agents inside the NPA or Communist Party who had been identified and interrogated.

Evidence suggests that Rowe’s Vietnam experience was not coincidental to his selection as a target. In June of 1989, from an NPA stronghold in the hills of Sorsogon, a province in Southern Luzon’s Bicol region, senior cadre Celso

Minguez told the Far Eastern Economic Review magazine that the communist underground wished to send “a message to the American people” by killing a Vietnam veteran.

“We want to let them know that their government is making the Philippines another Vietnam,” Minguez, a founder of the communist insurgency in Bicol and participant in the abortive 1986 peace talks with President Corazon Aquino’s

government told the REVIEW.

In May 1989, U.S. Veteran News and Report reported that according to a source who had served under Rowe, the Vietnamese communist also wanted Rowe dead and very likely collaborated with the Philippine insurgents to achieve that goal.

The source who wished to remain anonymous said that prior to Rowe being assigned to the Philippines in 1987, at one point in Greece while Rowe was on assignment, Delta Force, the U.S. anti-terrorist organization, moved in,

secured the area and relocated Rowe. They had received reports that Vietnamese communist agents were planning an action against Rowe.

“He was a target when he went over there because of his dealings with the North Vietnamese and his time as a prisoner,” Robert Mountel, a retired Special Forces colonel and former commander of the 5th Special Forces Group, subsequently explained, confirming what the other source had said. “They had him on their list.”

Despite the clear danger especially posed to Rowe and other intelligence operatives, Rowe was not given a heavily armored car to travel in. One reason for this, U.S. Veteran News and Report has learned, is that budget cuts for the Defense Attache System (DAS) for 1989 had resulted in a 72 percent cut in the DAS’s vehicle armoring program, causing the program to be canceled entirely last year (except for a skeleton infrastructure maintained to handle basic functions). This had a direct impact on the DAS’s ability to provide adequate security to U.S. personnel abroad, according to a well-placed intelligence source.

The book “Pacific Stars and Stripes, VIETNAM Front Pages” published in 1986

states:

Five Star Edition

Vol. 19, No. 304

Friday, November 1, 1963

3 Aides Seized in Vietnam Battle

Saigon (AP) Communist guerrilas smashed a Republic of Vietnam task force after disrupting its radio communication Tuesday, and probably captured all three U.S. Army advisers with the 120-man Saigon outfit.

The three Americans listed as missing and believed captured were two officers and an enlisted medic. Stragglers returning from the rout said both officers had been wounded early in the fight — one in the head and one the other in the leg.

The Army identified the three as Captain Hubert R. Versace, Baltimore; First Lieutenant James M. Rowe, McAllen Texas; and Sergeant Daniel L. Pitzer, Spring Lake, North Carolina.

A second government force of about 200 men operating only a few thousand yards from the main fight, learned of the disaster too late to help. U.S. authorities said the communist radio jammers had knowcked out both the main channel and the alternate channel on all local military radios.

Five Star Edition

Vol 21, No. 270

Tuesday, September 28, 1965

Report 2 Advisers Executed

Saigon (UPI) — The viet Cong executed two captive servicemen Sunday morning, the clandestine Liberation Radio said late Sunday night.

The communist radio identified the two Americans as Captain Albert Rusk Joseph and Sergeant Kenneth Morabeth (as received phonetically).

American authorities in Saigon were comparing the names with a list of missing American servicemen to determine if any such individuals were, indeed, communist captives. The reported executions came less than three days after the Vietnamese government’s execution of three convicted Viet Cong terrorists in Da Nang.

In revenge for the last previous execution of a Viet Cong by the government. the communists announced that they had executed Sgt. Harold Bennett, of Arkansas, on June 24.

Colonel Rowe is buried in Section 48 lot 2165-A of Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard