Courtesy of the Food & Drug Administration:

Harvey Washington Wiley was born in a log farmhouse in Indiana, in 1844. He served as a corporal in the Civil War and was then a top graduate of Hanover College (1867). Wiley then studied at Indiana Medical College where he received his M.D. in 1871.

After he graduated, Wiley accepted a position teaching chemistry at the medical college, where he taught Indiana’s first laboratory course in chemistry beginning in 1873. Following a brief interlude at Harvard, where he was awarded a B.S. degree after only a few months of intense effort, he accepted a faculty position in chemistry at the newly opened Purdue University in 1874. In 1878, Wiley travelled overseas where he attended the lectures of August Wilhelm von Hoffman the celebrated German discoverer of several organic tar derivatives, including analine. While in Germany, Wiley was elected to the prestigious German Chemical Society founded by Hoffman. Wiley spent most of his time in the Imperial Food Laboratory in Bismarck working with Eugene Sell, mastering the use of the polariscope and studying sugar chemistry.

Upon his return to Purdue, Wiley was asked by the Indiana State Board of Health to analyze the sugars and syrups on sale in the state to detect any adulteration. He spent his last years at Purdue studying sorghum culture and sugar chemistry, hoping, as did others, to help the United States develop a strong domestic sugar industry. His first published paper in 1881 discussed the adulteration of sugar with glucose.

Wiley was offered the position of Chief Chemist in the U. S. Department of Agriculture by George Loring, the Commissioner of Agriculture, in 1882. Loring was seeking to replace Peter Collier, his current Chief Chemist, with someone who could employ a more objective approach to the study of sorghum, the potential of which as a sugar source, was far from proven. Wiley accepted the offer after being passed over for the presidency of Purdue, allegedly because he was “too young and too jovial,” unorthodox in his religious beliefs, and also a bachelor. Wiley brought with him to Washington a practical knowledge of agriculture, a sympathetic approach to the problems of agricultural industry and an untapped talent for public relations. After assisting Congress in their earliest questions regarding the safety of the chemical preservatives then being employed in foods, Wiley was appropriated $5,000 in 1902 to study the effects of a diet consisting in part of the various preservatives on human volunteers.

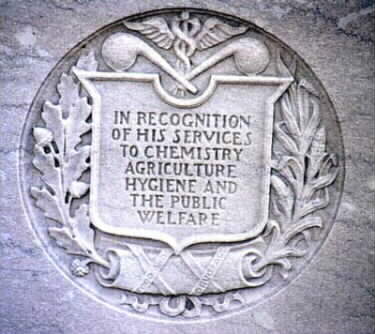

These famous “poison squad” studies drew national attention to the need for a federal food and drug law. Wiley soon became a crusader and coalition builder in support of national food and drug regulation which earned him the title of “Father of the Pure Food and Drugs Act” when it became law in 1906. Wiley authored two editions of Foods and Their Adulteration (1907 and 1911), which detailed for a broad audience the history, preparation and subsequent adulteration of basic foodstuffs. He was also a founding father of the Association of Official Analytic Chemists, and left a legacy to the American pure food movement as its “crusading chemist” that was both broad and substantial.

The fact that enforcement of the federal Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906 was given to the Bureau of Chemistry rather than placed in the Department of Commerce or the Department of the Interior is a tribute to the scientific qualifications which the Bureau of Chemistry brought to the study of food and drug adulteration and misbranding. The first food and drug inspectors were hired to complement the work of the laboratory scientists, and an inspection program was launched which revolutionized the country’s food supply within the first decade under the new federal law. Wiley’s tenure, however, was marked by controversy over the administration of the 1906 statute which he had worked so hard to secure. Concerns over preserving chemicals, which had not been specifically addressed in the law, continued to be controversial. The Secretary of Agriculture appointed a Referee Board of Consulting Scientists, headed by Ira Remsen at Johns Hopkins to repeat Wiley’s human trials of preservatives. The use of saccharin, bleached flour, caffeine, and benzoate of soda were all important issues which had to be ultimately settled by the courts in the early days under the new law. Under Wiley’s leadership, however, the Bureau of Chemistry grew significantly, both in strength and in stature after assuming responsibility for the enforcement of the 1906 Act. Between 1906 and 1912, Wiley’s staff expanded from 110 to 146 and in 1910 the Bureau moved into its own building. Appropriations, which had been only $155,000 in 1906 were $963,780 in 1912. In 1912, Wiley resigned and took over the laboratories of Good Housekeeping Magazine where he established the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval and worked tirelessly on behalf of the consuming public.

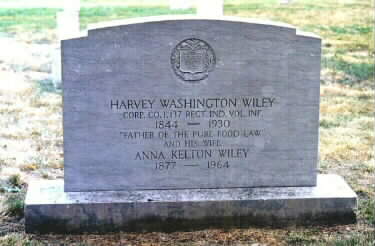

Harvey Wiley died at his home in Washington in 1930, and was buried in Section 13 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Published: Friday, April 28, 2006

A legacy to savor with each bite

Bothell woman proud to be the granddaughter of FDA’s founder

By Kristi O’Harran

Perhaps no one will feel compelled to rush to the June 30 centennial celebration of the Pure Food and Drug Act at the Harvey W. Wiley Federal Building in College Park, Maryland.

Adelaide Wiley Loges of Bothell, the granddaughter of Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley, isn’t planning to attend the event either, but that doesn’t mean that Loges isn’t busting her buttons about her relative, who founded the Food and Drug Administration.

We should thank the FDA for creating standards that prevent bread from containing sawdust, bar butter from being colored with poisonous yellow pigments, and help us feel confident that penicillin is really penicillin.

Bless the FDA for those protections.

Loges never got to meet the father of the Pure Food and Drug Act. In the 1880s, when Wiley began his 50-year crusade for pure food standards, harmful products were sold at most markets. According to his biography, because there were almost no government controls, manufacturers substituted cheap ingredients for those on labels. Honey was diluted, cottonseed was pressed and sold as olive oil, and “soothing syrups” given to babies were laced with morphine.

Wiley was born in a log cabin in 1844 on a farm in Indiana. His father, a schoolteacher, saw to it that his children had a basic education. Wiley went on to earn a degree at Indiana Medical College and a science degree at Harvard University. By his late 30s, he was a professor of chemistry at Purdue University.

In 1883, he moved to Washington, D.C., as chief chemist in what is now the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He continued his private passion of developing tests for food purity.

Through the 1890s, pure-food bills were introduced into Congress largely through Wiley’s work, but all failed. To bring his cause to the public in 1902, Wiley organized a volunteer group called the Poison Squad. They tested chemicals and tainted foods on themselves.

Wiley’s work was acknowledged in 1906 when President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Pure Food and Drug Act, written largely by Wiley, who was hired to run the new FDA.

The battle was won, but not the war. Wiley tired of his adversaries in Congress and the food and patent-medicine industries. In 1912, he left his government post.

A headline of the day read: “Women Weep as Watchdog of the Kitchen Quits.”

Wiley then worked as a chemist in the Good Housekeeping Institute laboratories and continued his fight for pure foods, tougher government meat inspections and butter not adulterated with water.

Wiley was ahead of his time. In 1927, he said any form of tobacco use might promote cancer.

In his last years, he saw to it that refined sugar was pure. When he died in 1930, at age 86, Wiley was given a patriot’s funeral at Arlington National Cemetery.

Wiley’s son, John, was Loges’ father. He attended the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and later worked for the Standard Oil Co. Descendants heard stories about their famous grandfather.

At her Bothell home, Loges cherishes a clock her grandfather received as a wedding present in 1911, a book he wrote and medals he received from France.

And it’s pretty cool to see your grandfather’s face on a 3-cent stamp from 1956.

Loges, 65, became a nurse and married an FDA chemist, Michael. They have one daughter. On the couple’s first date, Michael didn’t believe Loges’ grandfather founded the agency, but he was soon convinced.

Loges remembers writing an essay in school about her famous relative, who has a building in Maryland named in his honor. The Bothell activist has joined demonstrations for the environment and peace.

Showing her beliefs came naturally for Loges. Her grandmother, Anna Kelton, married Wiley in 1911. Kelton Wiley was a suffragette who was jailed after a demonstration to urge that women be given the right to vote.

Anna Kelton Wiley had the full support of her chemist husband, who understood the need to stand tall for principles.

WILEY, HARVEY

CORPL 1 37TH IND INFTY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 06/30/1930

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 07/02/1930

- BURIED AT: SECTION FIELD SITE 6969-B

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

WILEY, ANNA KELTON WIDOW OF HARVEY W

- DATE OF BIRTH: 03/08/1877

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/06/1964

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 01/10/1964

- BURIED AT: SECTION 13 SITE 5959-B

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY - WIFE OF HW WILEY CPL I CO 137 IND INF USA

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard