His wartime career began with the repulse of the Japanese advance in New Guinea and ended with the aerial offensive against the Japanese homelands. Following the war he served as Chief of the Air Defense Command in the United States.

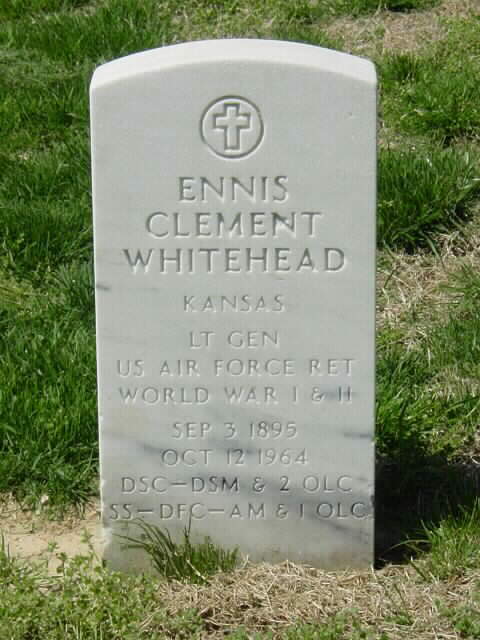

He died at San Antonio, Texas, October 12, 1964 and was buried in Section 34 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Courtesy of the United States Air Force:

Ennis Whitehead is another of the largely forgotten figures of American airpower, although he played an important role at an important time. Enlisting in the Army in 1917, Whitehead quickly joined the Air Service, won his wings, and was sent to France. He was an excellent pilot, but as a result he was made a test pilot and thus saw no combat. After the war, his reputation as an aviator grew within the small coterie of military airmen: he participated in Billy Mitchell’s bombing tests against the Ostfriesland in 1921, joined the Pan American flight of 1927-where he narrowly escaped death in a midair collision over Buenos Aires-and set a speed record from Miami to Panama in 1931. When war came, he was sent to the Pacific where he became George Kenney’s strong right arm. Whitehead stayed in Asia for the next seven years, becoming commander of the Fifth Air Force in 1944; and after Kenney left the theater, he took over the Far East Air Forces. Returning to the States in 1949, Whitehead commanded the shortlived Continental Air Command and then the Air Defense Command until his retirement in 1951.

His story is told by Donald M. Goldstein in “Ennis C. Whitehead: Aerospace Commander and Pioneer” (PhD dissertation, University of Denver, 1970). Goldstein, who later went on to edit the immensely popular histories begun by the late Gordon Prange, argues that Whitehead was a tactical genius and the brains behind such stunning air victories as Wewak, Rabaul, Gloucester, and Bismarck Sea. In addition, although Kenney has received credit for such innovations as skipbombing, parafragbombs, nose cannons in medium bombers, and the use of mass troop transport, Goldstein argues that it was Whitehead who actually pioneered them. The research here is impressive, but he is unable to do more than assert his points rather than prove them. Unquestionably, Whitehead was an outstanding tactician who performed extremely well in the Southwest Pacific theater, but attempting to pinpoint credit is generally far more difficult than assigning blame. Victory does have a thousand fathers. In addition, Goldstein repeatedly states that Whitehead was an outstanding planner, but it is not explained precisely what this means: how did he actually go about the crucial business of determining objectives, allocating resources, anticipating enemy counters, and measuring results? Whitehead himself emerges in this portrait as a hard, uncompromising man with a heavy twinge of antiSemitism and chauvinism; he was a good combat commander who engendered respect rather than admiration among his subordinates. He was also seen by some in the Air Force hierarchy as too attached to Kenney and MacArthur, too political, too outspoken, and too tactically focused. He was disgusted by the appointment of Hoyt Vandenberg rather than Kenney as chief of staff in 1948 and was outraged when the new chief quickly relieved Kenney as commander of Strategic Air Command. Reputedly, he also resented not being named vicechief of staff or receiving a fourth star. These feelings, combined with ill health, caused him to tender his resignation in early 1951. Despite Goldstein’s obvious and exaggerated affection for his subject, this is

a very solid piece of scholarship.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard