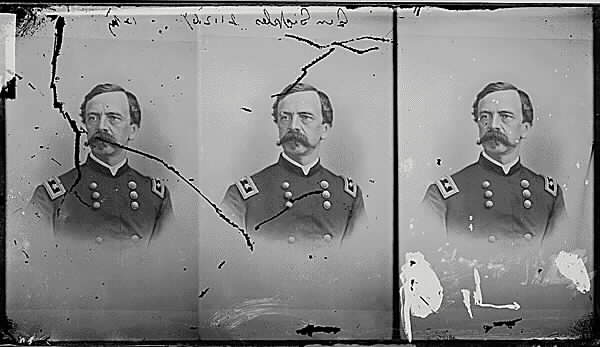

Always a controversial figure, Sickles was born on October 20, 1819 in New York City. After attending New York University and studying law, he appraised his chances for advancement in various fields and quickly chose politics.

As a Tammany Hall stalwart he became the Corporate Consul of the City at the age of 28 but resigned the same year to be Secretary of the U.S. Legation in London. He then served as a New York State Senator and Representative in Congress from 1857 to 1861.

He had first gained national attention when in 1859 he shot and killed, in the very shadow of the White House (on Lafayette Square), his young wife’s lover, Francis Barton Key, the son of Francis Scott Key, the author of the Star Spangled Banner. During the ensuing trial, in which he was represented by Edwin M. Stanton (who would become Lincoln’s Secretary of War), he for the first time in U.S. jurisprudence pleaded the “unwritten law” (self defense of one’s wife as his own property) and was acquitted. He subsequently enraged both critics and fans by publicly forgiving his unfaithful spouse.

As a War Democrat in 1861, his offer of services was quickly accepted by the President and he was soon appointed Brigadier General of Volunteers, ranking from September 1, 1861. He was assigned command of New York’s Excelsior Brigade, which he had been instrumental in recruiting.

His later career as a Division and Corps Commander, with his promotion to Major General to rank from November 29, 1862, found him often at odds with his superiors. However, he demonstrated many soldierly qualities and he was utterly fearless in combat. He fought on the Peninsula and at Sharpsburg in Joseph Hooker’s Division of III Corps; commanded a Division at Fredericksburg; and in the campaign of Chancellorsville commanded III Corps. In the latter battle, elements of his command reported that General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s celebrated flanking march, while it was still in progress, as a retreat. The subsequent advance of 2/3 of the Corps to pursue the “retreating” Rebels left Oliver O. Howard’s XI Corps on its right completely isolated and contributed largely to the ensuing debacle.

At Gettysburg, his men were supposed to cover the Federal left in the vicinity of the Round Tops. Not liking the position and in defiance of direct orders to the contrary, he advanced the Corps into the famous Peach Orchard, creating a salient which was subsequently overrun by General James Longstreet’s assault. The end results were the virtual destruction and disappearance if III Corps, termination of his command in the field by virtue of a serious wound which cost him his right leg, and controversy with his superior, General George Gordon Meade. However, he was subsequently awarded the Medal of Honor for his services at Gettysburg. After his recovery, during which he donated his amputated right leg to the Army Medical Museum in Washington – where it continues on display at that facility located at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, President Lincoln dispatched him on a tour of Union-held Southern territory for an appraisal of the effect of amnesty, Negro progress, and Reconstruction.

He next performed a diplomatic mission to Colombia; served as Military Governor of South Carolina; and in 1869 retired from the Army with the rank of Major General in the Regular Army. At that time, President Grant appointed him Minister to Spain, where he was chiefly distinguished diplomatically by becoming the intimate friend of Isabella, the former Queen of Spain. He served again in Congress from New York, 1893-95; and for many years was the Chairman of the New York State Monuments Commission, a position from which he was removed in 1912 by reason of alleged misuse of funds. However, while in that position, he did much to bring about the National Battlefield Park at Gettysburg, a site he often visited during his life.

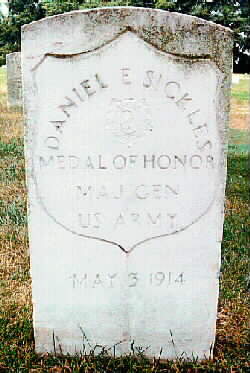

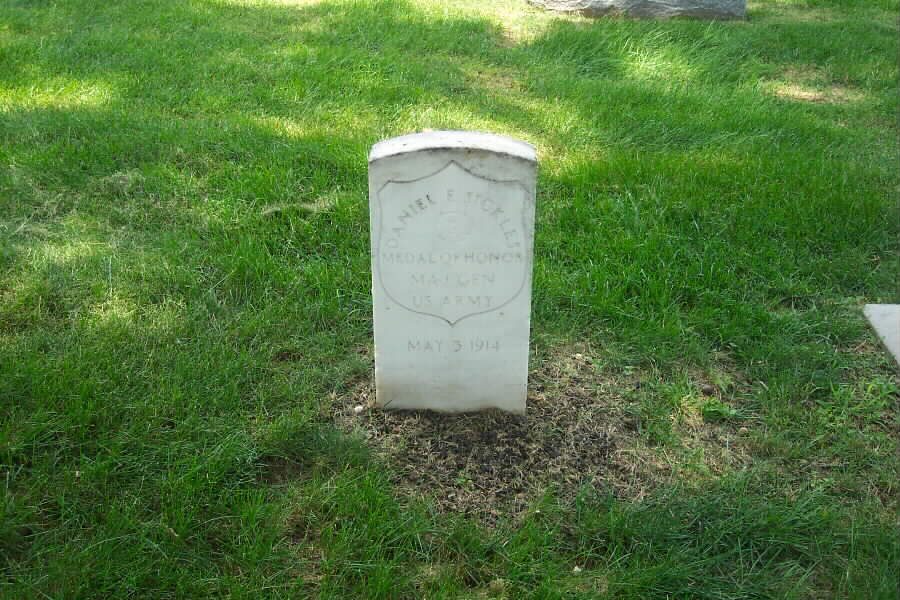

An octogenarian relic of a bygone age, he became separated not only from family but from reality and died irresponsible on May 3, 1914 at his home in New York City. He is now buried in Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Major General Daniel E. Sickles, Union Third Army Corps commander, was struck by a cannonball during

the battle of Gettysburg. Sickles was on horseback when the 12-pound ball severely fractured his

lower right leg. Sickles quieted his horse, dismounted, and was taken to a shelter where Surgeon Thomas

Sims amputated the leg just above the knee. Shortly after the operation, the Army Medical Museum received

Sickles’ leg in a small box bearing a visiting card with the message “With the compliments of Major General D.E.S.”

The leg of General Sickles

On Display At The Walter Reed Army Medical Center

American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles by Thomas Keneally: a review by Marianne Moates

American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles by Thomas Keneally.

If you think scandals at the highest levels of government and a trial of the century are topics just for today’s headlines, think again. America had a genuine scoundrel in the mid 1850s, Congressman Dan Sickles, a decorated war general, who murdered his wife’s lover in front of the White House.

The life of Dan Sickles is explored in the biography, American Scoundrel, by internationally acclaimed author, Thomas Keneally. Keneally is the author of numerous books, the most famous being Schindler’s List.

Keneally came upon information about Dan Sickles while researching the life of Thomas Francis Meagher, charming leader of an Irish uprising who immigrated to America. He then became active in the Democratic Movement known as Tammany Hall. This is where Meagher and Dan Sickles became friends and political leaders.

Sickles was a handsome man, articulate, well known leader in Tammany Hall politics. Though he had many affairs, he did not marry until he met the lovely young Teresa Bagioli whose parents were wealthy.

The Sickles’ moved to Washington where they were heavily involved in the political social swirl. The time was pre Civil-War and at every social gathering there were heard many rumblings of war.

Sickles continued his love affairs, and in the meantime seriously neglected his young wife. It did not take her long to fall into the arms of Phillip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key.

Key followed Teresa everywhere, to her social gatherings, and to her home. Dan Sickles eventually received a poison pen letter informing him of his wife’s infidelity. Like a modern sleuth, Sickles discovered for himself the embarrassment of Teresa’s indiscretions.

Sick with rage, Dan lay wait for Key and murdered him. Dan went to jail, and all of Washington turned out to comfort him. He pled insanity, and it was the first time the insanity defense had been used. It was Dan Sickles, of course, who had been driven insane by his wife’s seduction, and thus was out of his mind when he shot Key. Or so said his lawyer. Sickles was a hero for saving all the other ladies of Washington from this rogue named Key.

Sickles went on to fight in the Civil War, became caught up in a controversial trial over a strategic battle, lived abroad for a time, and had an affair with the deposed Queen of Spain.

Perhaps the most touching scene in the book is Sickles’ return to the battlefield at Gettysburg for the fiftieth anniversary celebration. He and some of the old Confederates embraced each other.

Sickles lived into his nineties. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with the full trappings due his rank as General.

This was a fascinating tale, well researched and documented. Anyone interested in history, especially history of the Civil War, would thoroughly enjoy reading the book.

Marianne Moates is a free lance writer who lives in Sylacauga. Her book reviews appear on Tuesdays.

From a contemporary news report:

“May 1993: The Gettysburg National Military Park, responding to a request for re-burying General Daniel E. Sickles there, says the remains could go in the Soldiers National Cemetery Annex or his ashes could be strewn in the original cemetery which has been closed to burials since 1903. An added section for Civil War and Spanish-American War interments behind the 1863 section would have been available for Sickles at his death in 1914, but he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. The added section was then closed in 1936. Gettysburg officials say that the National Park Service, Arlington National Cemetery and others would have to approve the re-burial proposed by New Yorkers Richard H. Davis and John V. Shad, Sickles’ great-great-nephew and his only known survivor. Davis says that Sickles should be buried in the historic section according to his wishes. They want him buried near the New York Monument.”

November 24, 1995: Sickles, who died in 1914, also was a murderer, a rogue and quite possibly a thief. Davis is a Delmar resident and Civil War aficionado who has taken on a one-man crusade on Sickles’ behalf. And now the twain have met. “He was so bad he was good,” Davis said, adding he has taken on cause because, well, because he felt like it.

Sickles, a Medal of Honor winner who lost a leg in the Battle of Gettysburg, gunned down Philip Barton Key, the son of the author of the Star Spangled Banner, within walking distance from the White House. Key was romancing Sickles’ wife, Davis said. Sickles was acquitted of murder when he used a temporary insanity defense. Sickles also was once censured for bringing a hooker onto the floor of the state Legislature. The general also is considered the “patron saint” of the Gettysburg Battlefield National Military Park The Civil War hero was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia following his death, possibly in contravention of his own and his wife’s wishes that he be interred adjacent to the New York State Monument at Gettysburg, Pa. And that has raised Davis’ hackles. After go-rounds with officials at both Arlington and Gettysburg, he is now seeking the backing of Bernadette Castro, commissioner of the state Department of Park, Recreation and Historic Preservation in his cause.

Davis also has persuaded Sickles only surviving relative, John Shaud of West Hempstead, Long Island, to formally back the moving of Sickles’ body . . . to no avail. “There’s not a chance in hell General Sickles is going to disinterred,” said John Latschar, superintendent of the Gettysburg National Cemetery. “It’s pretty simple, I wouldn’t even call it an issue,” he added. “It would take a court order to get him out of Arlington, I’m certainly not going to support that.”

Quite simply, said Latschar, “Mr. Davis has got some vague circumstantial evidence pointing to the fact that Sickles’ estranged wife may have wanted him at one time to be buried here.” He has a strong case, said Davis, who participated in the annual Remembrance Day Parade marking Abraham Lincoln’s deliverance of the Gettysburg Address, last weekend at Gettysburg while dressed as Sickles. Davis points to a 1914 New York Time article that says Sickles’ widow had asked the federal secretary of war for permission to have her husband buried at the Gettysburg monument. The secretary granted permission. “This disposed of the idea that the body might be brought to Washington for burial at Arlington,” said the Times at the time. He also cites federal records noting that Mrs. Sickles asked that her husband be buried near the New York State Monument. The reply from a Colonel John P. Nicholson to Assistant War Secretary Henry Breckinridge notes: “Cannot be slightest objection to Sickles’ interment as specified.”

“There’s no good paper trail or documentation to detail how that decision was made,” responded Latschar. “General Sickles was very much involved with Gettysburg; he was instrumental getting involved with the national park. We have to make the logical assumption if he wanted to be buried here at the cemetery, it would have been a well-known fact.”

Without that Davis needs either a court order or the request of a blood relative for the disinterment, he said. “Mr. Davis has found some long lost nephew, that just doesn’t cut the ice,” Latschar said. Shaud said he strongly supports the movement of his great grand-uncle to the Gettysburg cemetery. And if the feelings of the only surviving relative carry no weight, what does, he asked? “What does he want? The poor man’s dead for 80 years. Does he want a son? His son died in 1939.”

Sickles, born in 1819, attended a private school in Glens Falls for a short time as a boy, later became a lawyer opening his first law office conveniently before he had even passed the bar. By 1837, he had been indicted for obtaining money under false pretenses. Afterward, Sickles became a politician and was involved with the Line is overdrawn infamous Tammany Hall Democratic bastion in New York City. He was elected to the state Assembly in 1847. He later was censured by that body when he brought well-known New York City bordello operator, Fanny White, onto the chamber floor for a tour. In February 1859 in front of a dozen witnesses in Lafayette Square in Washington, he shot down Key in the dispute over Key’s interest in Sickles’ young wife. “Of course I killed him,” he said at the time. “He deserved it.”

At Gettysburg, he lost his leg when he was hit by a cannon ball, Shaud said. President Abraham Lincoln and his son, Tad, visited the general in a Washington Hospital. During the 1890s, as a federal congressman, he successfully lobbied for the establishment of the Gettysburg battlefield park.

Ironically, the fence along Lafayette Square where the Key killing took place was later moved to the border of the Gettysburg cemetery, said Davis. At last weekend’s Remembrance Parade, Latschar was there, laughed Davis. “He was very somber, never said a word. He looked, I made sure he saw me having a good time.”

So how did Davis become the world’s biggest Dan Sickles backer? Davis said he became interested in Sickles during a Civil War conference several years ago. Davis didn’t like the reaction that followed a discussion on Sickles and his command of the Third Corps during the crucial second day of the Gettysburg battle.

“Everybody was booing Sickles; that made it interesting, so I figured I’d defend him.” Since then, Davis has impersonated Sickles at various occasions and historical reenactments. And his friendship with an elderly retired Army colonel and historian put him on the trail of Sickles’ widow’s telegram and the reply giving her permission to bury dear old Dan at Gettysburg. A spokesman for state Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation said the department is aware of Davis’ October 25, 1995 letter seeking her to join his crusade. No immediate reply was available from the department on its position. Davis said he might seek to bring federal Attorney General Janet Reno into the fray.

“The National Park Service has shafted us,” he complained. “No one in New York state even knows about it.” As for Latschar, Davis has only contempt, noting that Sickles was the driving force behind the establishment of the national battlefield park and at Gettysburg. “He wouldn’t have a job if it wasn’t for Dan Sickles,” he said.

Representative from New York; born in New York City October 20, 1819; attended New York University; apprenticed as a printer; studied law; was admitted to the bar in 1846 and commenced practice in New York City; member of the State assembly in 1847; corporation attorney in 1853; secretary of the legation at London by appointment of President Franklin Pierce 1853-1855; member of the State senate in 1856 and 1857; elected as a Democrat to the Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth Congresses (March 4, 1857-March 3, 1861); was not a candidate for renomination in 1860; served in the Civil War as colonel of the Seventeenth Regiment, New York Volunteer Infantry, and brigadier general and major general of Volunteers; retired with rank of major general April 14, 1869; awarded the Medal of Honor October 30, 1897, for action at the Battle of Gettysburg; entrusted with a special mission to the South American Republics in 1865; chairman of the New York State Civil Service Commission in 1888 and 1889; sheriff of New York City in 1890; elected as a Democrat to the Fifty-third Congress (March 4, 1893-March 3, 1895); unsuccessful for reelection in 1894 to the Fifty-fourth Congress; resided in New York City until his death there May 3, 1914; interment in Arlington National Cemetery.

In 1859, Capital Was a Wild, Wild Washington

Daniel E. Sickles was astonished. When he looked out the window of his mansion at Lafayette Square, the congressman saw his wife’s lover signaling her in broad daylight, waving a white handkerchief toward her bedroom window. Enraged, Sickles grabbed two derringers and a revolver, left the house and strode to the other side of the park, where he found his prey, Philip Barton Key.

“Key, you scoundrel. You have dishonored my home,” Sickles said, according to witnesses. “You must die.”

It was about 2 p.m. Sunday, Feb. 27, 1859, and at least 12 people would witness all or part of the bloody scene between Sickles, a Democratic U.S. representative from New York, and Key, the U.S. attorney for the District.

Sickles fired a gun, the bullet grazing Key. The two men struggled together at the southeast corner of Lafayette Square, right across from the White House, and Key retreated into the street, reached inside his coat and tossed his opera glass at his

pursuer. Sickles, who was within 10 feet of Key, fired a bullet that struck Key below the groin, passing through his thigh. Key staggered over to a tree, leaned against it, then fell. He cried, “Don’t shoot me!” and “Murder!”

But Sickles pulled the trigger. The gun misfired. Sickles fired again, fatally wounding Key in the chest, according to Nat Brandt in his 1991 book “The Congressman Who Got Away With Murder.”

Sickles and Key, both dapper, about 40 years old and part of Washington’s social elite, had been friends before Key, the son of Francis Scott Key, started a torrid and rather public love affair with Sickles’ young wife, Teresa.

The deadly rivalry that evolved between the two men took place only two years before the Civil War pitted brother against brother. But the slaying had nothing to do with the politics of North vs. South. It had a lot to do with the sometimes violent,

frontierlike quality of mid-19th-century Washington.

The capital was a city of contrasts in the decade capped by the slaying case. Elegant balls were held in beautiful houses, yet residents dumped garbage in the alleys, and pigs scavenged freely in the streets. W.W. Corcoran commissioned the design of a splendid gallery for his art collection, yet robbery, assault, thievery and prostitution thrived as the city grew rapidly.

By 1858, a year before the Key slaying, a Senate committee had issued a written report noting that ” ‘riot and bloodshed are of a daily occurrence. Innocent and unoffending persons are shot, stabbed and otherwise shamefully maltreated, and not infrequently, the offender is not even arrested,’ ” according to the 1962 book “Washington Village and Capital, 1800-1878,” by Constance McLaughlin Green.

And it didn’t help that the vast transient population that flooded Washington when Congress was in session “came from states or territories where the border between urbane urban living and rustic rural frontier brushed close,” wrote Brandt.

Violence and other vices were not confined to the lower rungs of society. Members of Congress carried guns (many for protection), gambled heavily, visited bordellos and were frequently drunk. ” ‘While the Democrats and Republicans were in a

deadly struggle on the floor of the House over questions involving the destinies of the Union,” complained Rep. John Kelly of New York, ” . . the [drunk congressmen] were in the [congressional] bar-room drinking, or on the sofas of the lobby dozing in their cups,’ ” according to Brandt.

During congressional sessions, fistfights “more than once ended in duels,” Green wrote. A congressman shot a waiter in a Washington hotel. On the floor of the Senate, an assailant threatened Thomas Benton of Missouri at gunpoint.

And tensions were high in Congress among some Northerners and Southerners, such as when Preston Brooks of South Carolina savagely caned Charles Sumner of Massachusetts.

To many people in the mid-19th century, a man who seduced another man’s wife was asking for it. Today the killing of Key is remembered chiefly because of the 20-day trial in which Sickles was acquitted of murder to the cheers of a crowded

courtroom.

Sickles, whose attorneys argued that he went mad because of anguish over the adultery, was the first defendant to use a “temporary insanity” defense in the United States. The trial, which garnered national press attention, made for juicy copy. Sickles’ formidable team of lawyers essentially put the dead man on trial.

“Whenever [Key] met her, the whole object of his acquaintance was the gratification of his lust,” defense attorney John Graham told the jury, according to an account of the trial published soon after the acquittal. Graham hammered away at Key’s “sin,” citing passages from the Bible, and arguing that Sickles’ “frenzy” was justifiable. The account, by Felix G. Fontaine, called the case “The Washington Tragedy” and sold for 25 cents a copy.

Sickles’ suspicions about his wife’s infidelity were confirmed by an anonymous note he received a few days before the killing. At the trial, lady’s maid Bridget Duffy testified to hearing sobs from the couple the night before the slaying, when Sickles

confronted Teresa in an upstairs bedroom.

Despite his distress, Sickles–who also was a lawyer–had the presence of mind to persuade Teresa to write a detailed confession. It was ruled inadmissible in court but nevertheless was printed in the newspapers. In the extraordinarily candid

document, Teresa described her numerous rendezvous with Key at a vacant home on 15th Street, a house that Key rented.

“There was a bed in the second story. I did what is usual for a wicked woman to do. . . I undressed myself. Mr. Key undressed also.” She described in detail her garments: “As a general thing, have worn a black and white woollen plaid dress,

and beaver hat trimmed with black velvet.”

Teresa also confessed to first having met privately with Key in the Sickles mansion. “Mr. Key has kissed me in this house a number of times. I do not deny that we have had connection in this house–in the parlor, on the sofa.” She signed it with her maiden name, “Teresa Bagioli.”

Teresa was about 20 years old and the beautiful wife of the newly elected congressman when she met the tall, dashing Key at President James Buchanan’s inauguration about two years before the slaying. The two subsequently grew friendlier at parties, which her husband often did not attend.

Key had rented the vacant house for their adulterous meetings in a racially mixed area, possibly as a weak attempt at privacy away from their social milieu. The house was only a few minutes’ walk from the Sickles home, and it was clear to nearby residents what was going on. Nancy Brown, who lived near the vacant house, testified that Key would enter the home and hang a string attached to an upstairs shutter. The string was a signal to Teresa that he was there.

Key was a scion of a prominent Maryland family. His late father, Francis Scott, was a lawyer who was famous for writing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” A widower with four children, Philip Barton Key was a well-known ladies’ man, with sad eyes and a languid charm, according to Edgcumb Pinchon in his 1945 book “Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and ‘Yankee King of Spain.’

” When Teresa met Key, she was enduring her husband’s own infidelities and his frequent absences on political business. Because of the double standard of the era, the well-known fact of Daniel Sickles’ affairs made no difference to much of the

public.

Key and Teresa soon became passionate about each other. Servants testified at the trial about their liaisons in the parlor of the Sickles home. And Teresa Sickles’ coachman, John Thompson, testified that Key (riding his iron-gray horse, Lucifer), would encounter Teresa between almost daily in the afternoon on the street and would frequently enter her carriage.

On several occasions they would visit the Congressional Cemetery on the city’s east side or the burying ground at Georgetown. “They would walk down the grounds out of my sight, and be away an hour or an hour-and-a-half,” Thompson said, according to the trial report.

The affair must have been particularly galling to Daniel Sickles because of his own friendship with Key, which was launched at a stag whist party in 1857, not long after the Sickles couple moved to Washington. Sickles even interceded with the newly elected Buchanan, who was a friend, to ensure that Key would be reappointed as U.S. attorney.

Ironically, Key’s brother, Naval Academy midshipman Daniel Key, had been killed in a duel about 1836 in the village of Bladensburg, just outside Washington. By the time of Barton Key’s slaying a quarter-century later, dueling had long been

outlawed in the District, but the Bladensburg dueling grounds were still being used by “gentlemen” to settle their differences.

Daniel Sickles’ emotional nature was evident throughout the case. Two days before the slaying, he showed the anonymous note about the affair to a friend, congressional clerk George B. Wooldridge, then “put his hands to his head and sobbed in the lobby of the House of Representatives,” Wooldridge testified.

After the slaying, Sickles turned himself in at Attorney General Jeremiah Black’s house a few blocks away on Franklin Square. Sickles initially was placed in a dark, filthy, vermin-infested cell at the Washington jail at Fourth and G streets, but soon was transferred to the jailer’s own office. There Sickles slept on a cot and received meals from home and visits from his 6-year-old daughter, Laura, famous political figures and even his greyhound Dandy, according to Brandt.

Sickles eventually reconciled with his wife, who asked for forgiveness. “God bless you for the mercy and prayers you offer up for me,” she wrote in a letter to her husband after the slaying. The press, which had championed his acquittal, criticized him for forgiving her.

Teresa was about 16 (and probably pregnant with their daughter) when she married Sickles in New York 6 1/2 years before the slaying, according to Brandt. Sickles, a New York assemblyman, was twice her age. He had been a longtime friend of her

parents, the well-known singing teacher Antonio Bagioli and his wife, Maria.

Sickles was a charismatic man who courted controversy throughout his life and held a succession of significant posts.

After the trial, he served as a controversial Union general during the Civil War (he clashed with another general about troop deployment), as a military governor of the Carolinas after the war and later as U.S. minister to Spain. Teresa took ill and died in 1867 at about the age of 31, and Sickles married a Spanish woman, converted to Catholicism and fathered two more children. (He was rumored to have had a romantic involvement with deposed Queen Isabella II.)

He later became sheriff of New York County, then served in Congress again from 1893 to 1895. He was chairman of the New York Monuments Commission from 1886 to 1912, when he was removed after accusations of embezzlement. He died at 94 in 1914 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The most telling story about Sickles’ gritty character stems from the time his leg was struck by a 12-pound cannonball at Gettysburg during the Civil War. He sent his freshly amputated limb to the new Army Medical Museum in Washington with a visiting card reading “with the compliments of Major General D.E.S.”

Two months after the injury, Sickles was back on his horse, and for many years he visited the leg bone on the anniversary of the amputation. It is still on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Northwest Washington.

Perhaps only a larger-than-life character such as Daniel Sickles could have gotten away with killing his wife’s lover in broad daylight. And perhaps it only could have happened when and where it did, in mid-19th-century Washington, a city distracted

by its own growing pains and impending hostilities between North and South.

At the time, though, the public regarded the story as a Victorian morality tale of a wronged husband avenging his wife’s seduction. Brandt’s book cites verses from a song written by an unidentified lyricist:

In the first place this Key he was a false friend, Sickles he thought that on him he’d depend, But the false-hearted villain, his honor betrayed, He took his wife away, and Sickles him he slayed.

- SICKLES, DANL E

- MAJOR GENERAL USA

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/03/1914

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SECTION WEST SITE 1906

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

SICKLES, DANIEL E.

Rank and organization: Major General, U.S. Volunteers. Place and date: At Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 2 July 1863. Entered service at: New York, N.Y. Birth: New York, N.Y. Date of issue: 30 October 1897.

Citation:

Displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.

Coverage By The New York Times

The Death of Major General Daniel Edgar Sickles

GEN. SICKLES DIES;

HIS WIFE AT BEDSIDE

Long Estrangement Ended When Fatal Illness Attacked Veteran

CAREER A STIRRING ONE

Soldier, Politician, and Diplomat

He Lost a Leg at Gettysburg, and Lived to be Almost 91

Major Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, commander of the Third Army Corps on the memorable field of Gettysburg, where one of his legs was shot off, and subsequently the representative of this Government at the Court of Spain, died last night at 9:10 o’clock at his home, 23 Fifth Avenue. Gen. Sickles was in his ninety-first year. At his bedsiade were Mrs. Sickles and his son, Stanton Sickles, who had been with him constantly for nearly two weeks, following a reconciliation that ended an estrangement of twenty-nine years. Also at the deathbed were John J. Kirby of 32 Nassau Street, counsel for Mrs. Sickles, and Miss Higgins, a trained nurse. Gen. Sickles was unconscious when the end came, having relapsed into that state several days ago. He had been ill for about two weeks, following an attack of cerebral hemorrhage. Gen. Sickles passed away just a few minutes before the arrival of his physician, Dr. J.H. Spann of 107 East Eleventh Street, who on Saturday night had entertained fears that the attack from which the famous old veteran was suffering, though slight, would prove fatal to him on account of advanced years.

Until recently Gen. Sickles had borne the weight of his years almost with a sprightliness. On March 29 a rumor was spread that he was at the point of death. Late that night a TIMES reporter called up Gen. Sickles’s house over the telephone to make inquiry about his condition. The voice at the other end of the wire said: “Yes; this is Gen. Sickles. Am I ill? Nonsense. I was never better in my life. There’s nothing to that story. It’s all a lie.”

Reconciled with His Wife

The reconciliation between Gen. Sickles and his wife and son was brought about, it was said, through the efforts of one of the General’s negro servants. Before they went to his bedside, Mrs. Sickles and Stanton Sickles were living at the Hotel Albert, University Place and Eleventh Street. They were unwilling to live with the General as long as Gen. Sickles’s secretary, Miss Eleanora Earle Wilmerding, lived at his home. Miss Wilmerding died recently, and that may have hastened the reconciliation.

Although estranged from her husband, Mrs. Sickles had lived near him with her son. In 1912, when she learned through the newspapers that the General was in financial straits, and that his household goods were about to be disposed of at a Sheriff’s sale, she went to his rescue with $8,000 she obtained by pawning her jewelry. A few days after Mrs. Sickles had rendered her husband this service, he issued a statement attacking her motives for doing so, and asserting that it was not necessary for her to pawn her jewels.

Mrs. Sickles, as Senorita Carmina Creagh, the daughter of Chevalier de Creagh of Madrid, a Spanish Councillor of State, was married to Gen. Sickles on Nov. 28, 1871, at the American Legation in Madrid, when the General was Minister to Spain. She was brought up in the Court, and was the niece of the Marchioness of Novaliches, the Mistress of the Robes of the Court of Queen Isabella. They had a son and a daughter.

The estrangement between Gen. Sickles and his wife has never been fully explained. Their marriage seemed to be a happy one until Gen. Sickles resigned as Minister to Spain and prepared to return to this country. His wife, however, without any explanation whatsoever, suddenly refused to accompany him. Later she reconsidered her determination and rejoined her husband in New York, only to leave him again and return to Madrid. That parting took place twenty-nine years ago. It was in 1908 that she returned to New York for the second time and took up her abode near the home of Gen. Sickles.

Had a Stirring Career

General Daniel E. Sickles was the last of that galaxy of corps commanders who made possible the achievement of Grant and brought our great civil strife to a triumphant close. Fighter, lawyer, politician, and diplomat, his life was a crowded one, and in his closing years he looked back through a vista of decades in which strife and trouble were mixed in greater proportion than triumph.

Daniel Edgar Sickles was born in New York City on Oct. 20, 1823. His grandfather, who was of Knickerbocker stock, retained the name of Van Sickles, but the father of Gen. Sickles dropped the Dutch prefix. Young Sickles was educated in the University of New York. hough his father was wealthy the young man preferred to strike out for himself. He took up the printer’s trade, at which he worked for several years. Then he entered the law office of Benjamin F. Butler, who was at that time Attorney General in President Van Buren’s Cabinet. He was admitted to the bar in 1846. He served in Congress from 1857 to 1861 and again in 1893-94. Butler was a leading Democrat, and he imbued the young law student with an enthusiastic devotion to that party. He was sent to the State Assembly by Tammany Hall in 1847. In 1852 he was a member of the Baltimore convention which nominated Franklin Pierce for the Presidency. For several years he was a member of the Tammany Hall General Committee. He was Corporation Counsel for a time, and in 1855 he went to the State Senate. It was he who obtained for the city its great Central Park.

Enlisted as a Private

The life of a soldier appealed to young Sickles, and he joined the Twelfth Regiment, National Guard, in 1849, as a private. In three years he retired from the organization as a Major. He rose to be a Major General in the United States Army later. In the Fall of 1853 Sickles was commissioned Secretary of Legation in London, under Minister James Buchanan. After serving two years abroad he returned to enter into the bitter political fight that sent him into the State Senate. Before his Senatorial term was out Sickles was elected to Congress. It was during his stay in Washington that an event occurred which became the sensation of the day. His ambition to fit himself for the diplomatic service had led him to take up the study of French and Italian, and in this way he met Therese Bagioli, daughter of an Italian music teacher. She was 17 when he married her. Their daughter, Laura, was born in 1854, on the old Sickles estate at Bloomingdale, while he was abroad as Secretary of Legation. When her husband went to Congress Mrs. Sickles accompanied him. Philip Barton Key, United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, son of Francis Scott Key, the author of “The Star Spangled Banner,” paid attention to Mrs. Sickles, and Sickles shot and killed Key on the street in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 27,1859. Sickles declared Key had misled Mrs. Sickles. His trial, which lasted twenty days, ended in the acquittal of Sickles, the defense being temporary abberation of mind, and this was the first case in which that plea was set up as defense. After his acquittal Sickles took his wife back.

Forgave His First Wife.

“I am not aware of any statute or code of morals,” said Sickles to his critics, “which makes it infamous to forgive a woman. I can now see in the almost universal denunciation with which she is followed to my threshold the misery and perilfrom which I have rescued the mother of my daughter. I shall strive to prove to all that an erring wife and mother may be forgiven and redeemed.” Mrs. Sickles died a few years later.

When Sickles went to Madrid years later his daughter Laura accompanied him. She fell in love with a young Spaniard. Her father objected to the match and brought her back to New York, where she died. Retiring from Congressin March, 1861, Sickles was one of the first to anticipate a need of soldiers. At the outbreak of the civil war, the young politician, then 38 years old, went to Lincoln to offer his services. “You have been a leader in New York Democratic politics,” said the President. “If you kept your end up at that game surely you’ll do to take command of men in the field.” The retired Congressman returned to this city and organized the Excelsior Brigade of Volunteers in New York, and was commissioned Colonel of one of the five regiments. He was nominated Brigadier General in September, 1861, but was not confirmed by the Senate until March, 1862. Gen. Sickles served under Gen. Hooker with distinction at Fair Oaks, and Malvern Hill. He was in the seven days’ fighting before Richmond and also participated at Antietam. He succeeded Gen. Hooker in command of the division, and took a conspicuous part in the engagement at Fredericksburg. He was appointed Major General of Volunteers in 1862, but his commission dated from the year previous.

Lost His Leg at Gettysburg

At Chancellorsville, commanding the Third Army Corps, to which he had been promoted, he was highly commended for gallant conduct, and his courage and activity at Gettysburg are matters of history. All authorities accord him a very important part in that great battle, some contending that his was the master stroke that saved the day. It was at Gettysburg that he lost a leg. In March, 1865, he was brevetted a Major General of the regular army for bravery and meritorious service at Gettysburg.

President Lincoln and Secretary Seward sent Gen. Sickles on a confidential mission to Colombia and other South American States early in 1865. He negotiated an important treaty regarding rights of transit over the Isthmus of Panama. Immediately upon his return to this country he was selected to play an important part in the task of reconstruction. He commanded the Military Department of the Carolinas in 1865-7 and performed his duties in a manner that elicited the cordial commendation of Secretary Stanton and Gen. Grant. The views of President Johnson differed from those of Gen. Sickles, however, and the President relieved Sickles of his command, and after first offering him the mission to the Netherlands, which he declined. He was mustered out of the service Jan. 1, 1868, and was placed on the retired list with the full rank of Major General April 14, 1869. In the Spring of 1869 President Grant having tendered to Gen. Sickles the mission to Mexico, which was declined, appointed him United States Minister to Spain, a post which he retained until March 20, 1874. After relinquishing that office to his successor Gen. Sickles continued to reside abroad, chiefly in France, until 1880.

Second Marriage in Spain

At the Court of Spain Sickles became a dominating figure. Four years of brilliant diplomacy brought him the title: “The Yankee King of Spain.” Here he contracted his second marriage with Senorita Creagh in 1877. This romance was followed by estrangement which was to last more than a quarter of a century. A son, Stanton, and a daughter, Edna, were the result of this marriage. The General returned to New York alone and reentered politics. He served as Sheriff of New York County and at the age of 67 was re-elected to Congress.

Trouble came to him in his last years.In June, 1911, his daughter, Mrs. Edna Sickles Crackenthorpe, wife of a British diplomat, sued to prevent a disposal of certain properties to which she believed she was entitled. In December, 1912, the General was deposed as Chairman of the New York Monuments Commission, which had headed during the twenty-six years of its existence. There was a shortage of $27,000, and there was some talk of arresting the old soldier, but nothing came of it. Another trouble came in 1911, when the New York Commandery of the Loyal Legion refused to admit Gen. Sickles to membership. He faced bankruptcy in the last years of his life, and several attempts were made to sieze the art treasures in his Fifth Avenue home because of debt. It was in his extremity that his estranged wife and son came to his aid on several occasions.

His last days were spent at 23 Fifth Avenue, surrounded by war relics and attended by his faithful negro servant/

From The New York Times, May 5, 1914:

EDITORIAL

DANIEL E. SICKLES

Nobody with warm blood flowing through his veins can read the obituary notices of Gen. SICKLES without a certain thrill of admiration. His was truly the adventurous spirit. Under the right inspiration, he might have been an intrepid explorer or a founder of thriving colonies. As it was, he filled many important positions in civil and military life and was always conspicuous in the minds of his contemporaries. He was in turn printer and lawyer, legislator and politician, an officer of militia, a Secretary of Legation, a volunteer soldier, rising rapidly to the rank of Major General and corps commander, and brevetted Major General in the regular army at the close of the war between the States; Minister to Spain, a post which he filled with distinction almost equal to that he achieved as a soldier; Sheriff of New York, and a Representative in Congress, for the second time, at 67, an age when most men are ready to retire.

He lived for nearly thirty years after that and many of them were years of activity. He was long a prominent figure in the social life of New York; until the decline of theglory of Wallack’s, no “first night” at that historic playhouse would have been complete without his presence. At the opera, in the era of STRAKOSCH and MAPLESON, he was always a conspicuous figure. He served on many public committees and was an appreciable force in civic development. His domestic life was marred by calamities which, unhappily, were always themes of public talk. He never quite lived down the effects of his mad action in 1859. Public sympathy at the time was largely with his victim, PHILIP BARTON KEY. But there was no disposition to withhold frank acknowledgement of his gallantry and military skill in the service of his country, and the loss of one of his legs in battle helped to keep the heroic side of his character in the public mind.

Men of his aggressive and impetuous nature seem to be barred from domestic contentment. DAN SICKLES, as he was called popularly for half a century or more, by friends and enemies alike, certainly had more than one man’s share of family troubles. It is all the more gratifying to know that his last hours were preceded by reconciliation, and that he died with his wife and son by his bedside. He was assuredly a picturesque and interesting character, and his long life was marked by many noteworthy achievements.

From The New York Times, May 6, 1914:

BURY SICKLES AT ARLINGTON

General Left Note Expressing Preference for National Cemetry

Major Gen. Daniel E. Sickles will not be buried at Gettysburg, but in Arlington National Cemetery, according to a statement made yesterday by his attorney, Daniel P. Hays. In April, 1910, Gen. Sickles visited Arlington with the late Major A.J. Zabriskie, at that time Secretary of the New York Monuments Commission, and expressed a desire to be buried there. Major Zabriskie made a note of this and informed his son, who told Mr. Hays. Confirmation is given in a note which Gen. Sickles left for Mr. Hays, in which he expressed a preference for Arlington. The funeral services will take place on Friday morning at 11 o’clock in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Mgr. Lavelle will officiate.

The body will escorted to the Cathedral from the residence at 23 Fifth Avenue by the Twelfth Regiment, New York National Guard, of which Gen. Sickles was once a member, twotroops of cavalry, and the First Battery, Field Artillery. Members of Phil Kearny Post, G. A.R., will also be in the escort, and other Grand Army men will be in line. Regular troops from Governors Island may also be in the guard of honor.

From The New York Times, May 8, 1914:

COMRADES IN ARMS MOURN GEN. SICKLES

Men Who Fought with Him Hold Simple Memorial Service Over His Coffin.

PLACE FLAG AND FLOWERS

Today They Serve as Pallbearers

At Service in Cathedral — Burial in Arlington.

White-haired comrades in arms of Major Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, commander of the Third Army Corps at the battle of Gettysburg held a memorial service last night over his bier in the Sickles home at 23 Fifth Avenue. Fifteen of the forty surviving members of the Phil Kearney Grand Army Post, to which he belonged, which was 500 strong at the close of the civil war, brought a last tribute to their late comrade, and the same fifteen old men will be the pallbearers in a more ceremonious memorial procession from the Sickles home to St. Patrick’s Cathedral this morning.

At the far end of the back parlor on the ground floor of the home, which was filled with friends and admirers of the late General, lay the mahogany coffin in which his body was reposed. Candles burned at the head and feet, and a flag was draped across his chest. A silver name-plate bore the words:

DANIEL E. SICKLES

Major General of the United States

Army

Born Oct. 10, 1820; Died May 3, 1914

The walls of the room were banked with floral tributes from hundreds of friends and admirers of the dead soldier. Mrs. Sickles and Stanton, her on, sat near the head of the bier. The fifteen old comrades of Phil Kearney Post sat around it with the post flag, the golden eagle of which was draped in black. The General’s old war cap, his sword, his golden epaulettes, lay at the foot of the bier. Gen. Edward Hetherton, Commander oif Phil Kearney Post, stood beside the coffin with the Memorial Committee of the Grand Army, consisting of Capt. William F. Kirchner, Grand Marshal; Adj. Gen. Isador Isaacs of McQuade Post 556, and Gen. John W. England of Hancock Post 259.

The memorial service was begun by Col. John R. Silliman of Aspinwall Post 600. The Chaplain of H.P. Clafin Post 558, Past Commander Thomas Robertson, delivered the prayer, and the memorial address was spoken by Gen. George B. Loud of W.S. Hancock Post 250. Col. Silliman read the simple but impressive ritual of the Grand Army, calling back to the assembled veterans the time when they stood shoulder to shoulder with their departed comrade in defense of their native land, reminding them that his and their devotion to duty would serve as an incentive to the youth f the land in ages to come, and warning them that soon they, too, would be called to join their late comrade at the Grand Encampment.

Then he called upon one of the comrades, and Col. Thomas M. Valleau, First Comrade, stepped to the coffin and laid a red rose, emblematic of friendship, upon the glass covering Gen. Sickles’s face. As he did so, he said simply: “In behalf of Phil Kearney Post, I lay this tribute on my comrade’s bier.”

Second Comrade, Col. John Rudmen, laid a laurel wreathe, symbol of fraternity, on the bier, repeating the formula of the First Comrade. Col. Henry G. Kopper, as Third Comrade, laid a white rose on the bier, as a token of purity, and repeated the formula. Then Col. Silliman laid a small silk flag upon the coffin, saying as he did so: “In behalf of the grand republic, in whose defense our beloved comrade, Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, devoted his life, I lay this flag upon his bier.”

All present then joined in the Lord’s Prayer.

In delivering the memorial address Gen. Loud explained that he was following the wish expressed by Gen. Sickles himself. “We stand by this coffin to-night,” he said, “and think of the heroic achievement of this man in the greatest battle of the world’s greatest war, of his heroic courage and sublime patriotism. He was a man of charming cheeriness, the memory of which will long survive in his comrades and friends. He had always a window open in his soul for humor and tenderness. Sunshine and shadow blended in his life. Melancholy and morbidness grasped at his soul, and in the twilight of his life he became in truth a man of sorrows. But the keynote of his career was ever an indomitable courage. He was a faithful friend and a generous foe. Anger, hatred, and revenge had no lodgement in his soul, but friendship, tenderness, and love blossomed there.”

At the conclusion of the memorial services the assembled veterans filed past the coffin, took a last look at the face of their old comrade, and passed out of the house. As they reached the street 100 boys of Alexander Battalion of United States Boy Scouts, led by Maj. James C. Smith, filed past and saluted solemnly. Mrs. Sarah F. Loomis, President of Lafayette Circle 3 of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic, of which Gen. Sickles was an honorary member, tendered to his widow the sympathy of her organization, as did also Mrs.Laura D. Prisk, District Instructor of the city for the G.A.R.

Among those present in the house were Daniel P. Hays, who has charge of the funeral for the family, and former Gov. William Sulzer, who lives on the top floor of the Sickles home.

At 10:15 o’clock this morning the coffin bearing the body of Gen. Sickles will be placed upon a gun caisson by the pallbearers, and the funeral procession will move up Fifth Avenue to St. Patrick’s Cathedral, escorted by the Twelfth Regiment, N.G.N.Y.; the Old Guard, Grand Army Posts, and a batalion of regular troops from Governor’s Island. A solemn requiem mass will be celebrated at the cathedral at 11:00 o’clock, Mgr. M.J. Lavelle officiating. After the services the troops will escort the body down Fifth Avenue to Thirty-sixth Street, west on Thirty-sixth Street to Seventh Avenue, and down Seventh Avenue to the Pennsylvania Station, where, at 3:34 o’clock in the afternoon, it will be taken with the funeral party in a special train to Washington. At Washington the body will be received by a special guard of the regular army, dispatched by Secretary of War Lindley M. Garrison, and will be guarded over night. In the morning a military guard, consisting of a firing squad and a chaplain, will escort the body to the National Cemetery at Arlington, Va., where it will be buried among many of Gen. Sickles’s old comrades of the Third Army Corps.

From The New York Times, May 10, 1914:

BURY SICKLES AT ARLINGTON

General’s Riderless Horse Follows

Caisson in Solemn Procession

WASHINGTON, May 9.–All the honors of war were paid to the late Major Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, who was buried in Arlington National Cemetery here today. The body of the veteran corps commander was carried in solemn procession from the Union Station, where it lay in state through the night, to the cemetery, accompanied by an escort of cavalry and field artillery. Following the caisson which bore the body, was led the General’s riderless horse. As the procession passed through the grounds of Fort Myer, a Major General’s artillery salute was fired, and at the grave three salvos of rifle shots and another artillery salute marked the placing of the body in its last resting place. The Rev. Father J.D. Houlihan, chaplain at Fort Myer, read the funeral service.

In addition to the regular army escort, a large number of civil war veterans marched in the procession.

The Controversy Continues: Where Should Daniel Edgar Sickles Be Buried?

Editorial note: The writer (see below) conveniently fails to mention that it was the request of General Sickles that he be buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Per the New York Times article of May 6, 1914, the General expressed this wish to the Chairman of the New York State Monuments Commisssion. This information was relayed to both the General’s son and his attorney. Accordingly, the arrangements were made for an Arlington burial at the time of the General’s death.

Would like Sickles’ to be buried here

Editor, Gettysburg Times:

Is the Pennsylvania Pillow Tax going to include the 867 New York veterans using the Gettysburg National Cemetery as their final resting place?

I read your Web site every day. I am a member of Civil War Matters, a non-profit New York State organization dedicated to the preservation of New York State’s involvement during and after the Battle of Gettysburg.

After reading all the articles about your “pillow tax” I would be remiss if I did not have opinion as a New York State historian, regarding New York at Gettysburg today.

There were 27,692 New Yorkers engaged in the battle, 5,063 were killed or wounded and 867 are buried there. That was New York State’s contribution in the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg.

In May of 1872, New York State contributed the largest sums of money, more than any other state, in establishing and maintaining the Gettysburg National Cemetery. In 1895 New York General Daniel Edgar Sickles established the Gettysburg National Military Park when he was the New York Congressman from the 10th New York Congressional District.

In 1998 the tourism in Gettysburg-Adams County contributed $275 million to the economic impact of Pennsylvania which included a state sales tax and will eventually, a “pillow tax.”

Every year, New Yorkers have been Gettysburg’s most frequent “tourist” according to the 1998 survey and “contributed” these taxes to the state of Pennsylvania and not to the Gettysburg National Military Park or the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

The Friends of National Parks at Gettysburg have two donation boxes, one of the Visitor Center and the other in the Cyclorama building fitted with see-through chambers for each state to make donations for monument restoration. New York and Pennsylvania receive the most donations, with New York averaging $9,000/year. This started over 10 years ago when milk bottles were used.

These donations by New Yorkers never reached the New York Monument for its restoration/preservation.

In 1990 “Civil War Matters” sent “NPS-DOI-Gettysburg” (National Park Service-Department of Interior) $7,072.83 for “cleaning/restoring the New York Monument in the Gettysburg National Cemetery.” These were the proceeds from the “West Point Civil War Seminar – 1990.” The $7,072.83 was stolen and N.P.S.-Gettysburg was very much involved in the theft. To date, the New York Monument has yet to be restored.

On “Monday, May 4, 1914”, a Colonel Nicholson of the Gettysburg National Cemetery and Secretary of War Garrison granted “Mrs. Sickles request General Sickles be buried near the New York Monument.”

On Dec. 7, 1992, the Sickles family requested that the General be reinterred in the Gettysburg National Cemetery as was originally “granted” in 1914. “That the expenses of this disinterment will be borne by the Sickles family.” The U.S. Army of Arlington National Cemetery (where Sickles was buried) approved of the Sickles disinterment provided “General Sickles be buried near the New York Monument.” Since the New York Monument in the Gettysburg National Cemetery is on the New York Plot (owned by New York State), New York Governor Mario Cuomo gave permission to the Sickles family to reinter the General in the New York plot on Nov. 14, 1989. General Sickles will be the only General who fought in the Battle of Gettysburg to be laid to rest close to the graves of his 867 comrades who he had led in the Gettysburg battle. Only veterans of the battle of Gettysburg were to be buried in the Civil War section of the Gettysburg National Cemetery which was closed in 1904.

The only opposition to General Sickles’ reinterment in the New York plot has been a National Park Service employee who ironically owes his employment to General Sickles when he established the Gettysburg National Military Park, in 1895, and a “historian” who has made his entire income from New York et. al. participation in the battle and President Lincoln. This “pseudo historian’s” income has only been from the contributions of others. And he opposes the reinterment of General Sickles!!!

It’s my opinion the time has come for New York’s Major General Daniel Edgar Sickles to be reinterred in the New York Monument plot on Monday, July 2, 2001, with the full military honors deserved for a Major General buried in a National Cemetery.

Richard H. Davis

Civil War Matters

Delmar, N.Y.

Family wants Sickles at Gettysburg

Editor, Gettysburg Times:

I attended the ceremonies prior to the demolition of the Gettysburg Tower on July 3.

I had heard or already read about Secretary Babbitt’s, Director Stanton’s and Superintendent Latschar’s views regarding “their obligation in preserving this sacred landscape.” That, “This is sacred ground. Americans come here to learn their past.”

The preservation of the Gettysburg battlefield began when New York Congressman Daniel E. Sickles established the Gettysburg National Military Park on Feb. 11, 1895.

On May 4, 1914 the War Department approved of Mrs. Sickles’ request of General Sickles being buried near the New York Monument in the Gettysburg National Military Cemetery, but on May 9, 1914, General Sickles was buried in the wrong National Cemetery, Arlington National Cemetery.

On Dec. 7, 1992, Arlington National Cemetery approved of the Sickles family (John Shaud’s) request for the disinterment of the General’s remains provided the General is reinterred “near the New York Monument” as Mrs. Sickles requested.

On Jan. 12, 1993, the then-Superintendent of the Gettysburg National Cemetery, Jose A. Cisneros, informed the Sickles family that there was room for General Sickles’ reinterment “near the New York Monument” but the burial permit will not be issued until July 3, 1995, the centennial year of General Sickles establishing the Gettysburg National Military Park.

In October 1994, John Latschar became the Superintendent of the Gettysburg National Cemetery and would not issue the burial permit for General Sickles reinterment “near the New York Monument.”

On July 3, 2000, Interior Secretary Babbitt, Director Stanton and Superintendent Latschar were on “the sacred landscape, fulfilling their obligation in preserving it by restoring it, as closely we can to the landscape of those days, for Americans to come here to learn about their past” or, restoring the battlefield back to the same way it was when Sickles preserved it in 1895.

Babbitt, Stanton and Latschar have refused to honor the Sickles family’s request for reinterment by not issuing the burial permit in the Gettysburg National Cemetery even after the U.S. Army of Arlington National Cemetery had approved of the General’s disinterment. The Sickles family is paying for the transfer of the General’s remains.

I believe that before Babbit et.al. continue with their approach on the preservation of the Gettysburg Battlefield they issue a burial permit now for General Sickles reinterment on Monday, July 2, 2001.

Richard H. Davis

Delmar, N.Y.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard