Tuesday, July 20, 1999

His steps on the moon were watched by millions who will never forget the “Whoopee” he shouted while promenading on the lunar surface.

It was typical Pete Conrad, friends said, as they buried the man Monday who was the third person to walk on the moon.

Conrad, known for his adventurous spirit, was killed July 8, 1999 when he crashed his Harley-Davidson motorcycle along a winding road in Southern California. He was 69.

“I’m not sure what he’s doing right now but I suspect he’s telling some stories of the old days,” Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk the moon, said, fighting back tears. “Pete was the best man I ever knew. He treated me like a brother.”

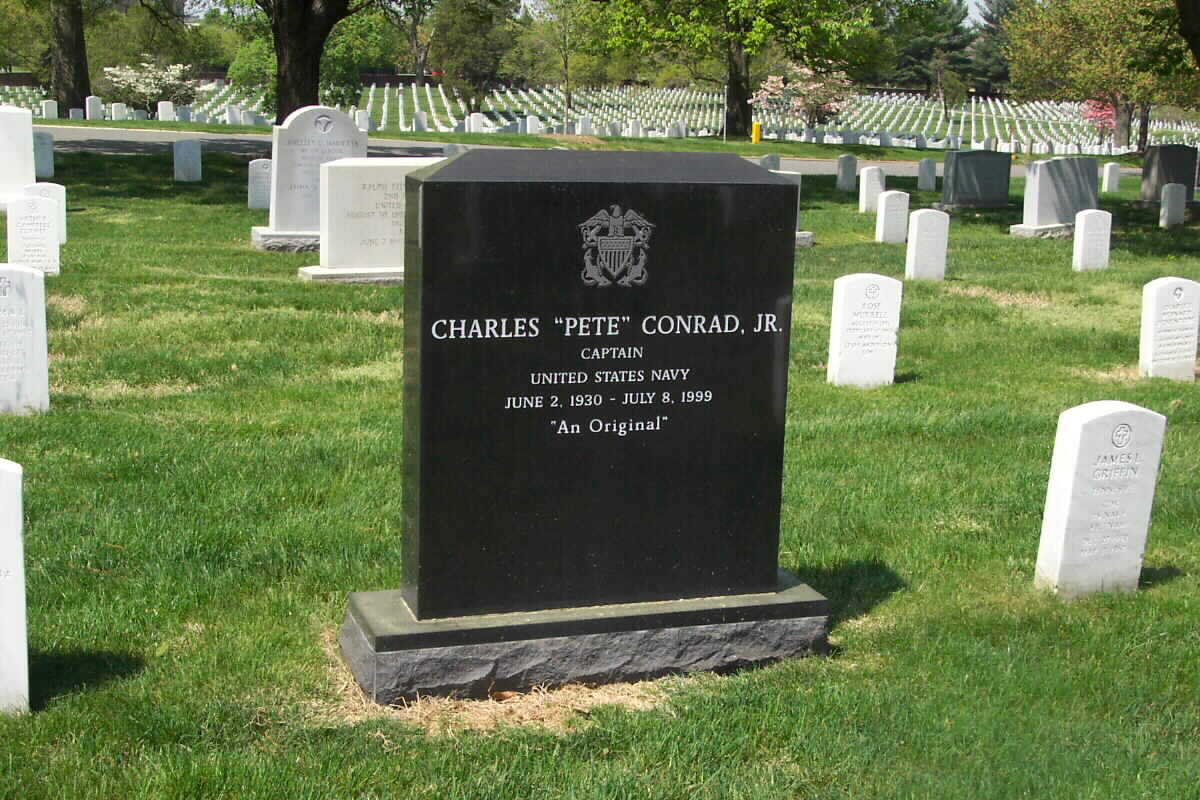

Conrad’s burial at Arlington National Cemetery brought together some of the nation’s space giants, including former Senator John Glenn, who last year made a return trip to space; Apollo 12 astronaut Alan Bean, Apollo 7 astronaut Walter Cunningham and Apollo 8 astronaut James Lovell.

Conrad, an Apollo 12 astronaut and former Navy captain, stepped onto the moon on November 19, 1969 — four months after Armstrong’s historic moonwalk and his “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Today is the 30th anniversary of Armstrong’s feat.

Besides the “Whoopee” remark, the fun-loving Conrad declared, “Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.”

At his burial, a horse-drawn carriage carried Conrad’s casket from a nearby military chapel as his widow, Nancy, sons and other mourners walked behind. A group of F-14 Tomcat aircraft flew over the service and a U.S. Navy firing party fired three shots. A Navy band played “Eternal Father” as the casket was loaded from the caisson.

Daniel Goldin, administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, described Conrad as “a man who had his feet planted firmly on the moon but always kept reaching for the stars.”

Conrad, Goldin said, is probably somewhere now with Apollo 14 astronaut Alan Shepard, who died last year.

“Pete’s star now joins Alan’s and others in that very special constellation,” he said.

The funeral procession of Charles P. Conrad at Arlington National Cemetery.

(Photo Courtesy of the United States Department of Defense).

Navy Ceremonial Team Folds The Flag At The Grave Of CharlesP. Conrad

(Photo Courtesy of the United States Department of Defense)

From Contemporary Press Reports:

Apollo 12 astronaut Pete Conrad, the third man to walk on the moon, will be buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery on July 19, 1999.

Conrad was killed in a motorcycle accident Thursday in Southern California. He was 69.

Several Apollo astronauts plan to attend the graveside service, said Howard Benedict, executive director of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation near Cape Canaveral. Details are still being worked out.

Family members and close friends will gather Sunday at the Conrad home in Huntington Beach, California, said Benedict. The astronaut is survived by his wife, Nancy, three sons and seven grandchildren.

Conrad, a former Navy captain, flew in space four times: twice during the Gemini program in the mid-1960s, as commander of Apollo 12 in November 1969, and as commander of NASA’s Skylab space station in 1973.

This 1969 file photo shows the crew of Apollo XII in

training: (L-R) Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard F. Gordon and Allan L. Bean

Lunar Pioneer Killed in California Accident

July 9, 1999

Courtesy of the Associated Press

Former astronaut Charles P. “Pete” Conrad, who in 1969 became the third man to walk on the moon, uttering an exuberant “Whoopie!” as he stepped on the lunar surface, died in a motorcycle accident. He was 69.

Conrad, who also flew two Gemini missions in the 1960s and commanded first Skylab mission in 1973, crashed on a turn yesterday (July 8, 1999) on Highway 150 near Ojai and died five hours later at Ojai Valley Community Hospital.

Conrad, who lived in Huntington Beach near Los Angeles, was on a trip to Monterey with his wife, Nancy, and friends, Ventura County Deputy Coroner James Baroni said.

Baroni said Conrad’s injuries didn’t initially appear to be severe, but he got worse after arriving at the hospital. He had some chest pain and had more trouble breathing.

“He showed that he had some type of internal bleeding and they needed to do exploratory surgery,” Baroni said. But doctors were unable to revive him.

Just this spring, Conrad joked that he was looking forward to the day he would turn 77.

“I fully expect that NASA will send me back to the moon, as they treated Senator [John] Glenn. And if they don’t do otherwise, why, then I’ll have to do it myself,” he declared.

Glenn became the oldest person in space at age 77 aboard the shuttle Discovery last year. Like Glenn, Conrad’s passion for space exploration never diminished. In 1995, he formed several companies with the goal of commercializing space.

“He was going back to space as an entrepreneur, trying to create ways for rockets to launch inexpensively and manage satellites,” Mrs. Conrad said Thursday evening.

NASA selected Conrad, an aeronautical engineer and Navy test pilot, as an astronaut in 1962, three years after the first seven astronauts were announced. He piloted the eight-day Gemini 5 mission in 1965, which set an endurance record in orbiting the earth. A year later, Conrad commanded Gemini 11, which docked with another craft during orbit and set a space altitude record of 850 miles.

As commander of the Apollo 12 mission in November 1969, Conrad earned the distinction of being the third man to walk on the moon after bringing the lunar module down in the moon’s Ocean of Storms.

The first two moonwalkers were Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, who landed there 30 years ago this month, on July 20, 1969. Armstrong’s first words became famous: “That’s one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind.”

When the 5-foot-6 Conrad stepped onto the surface four months later, he exclaimed with his trademark sense of humor: “Whoopie! That may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.”

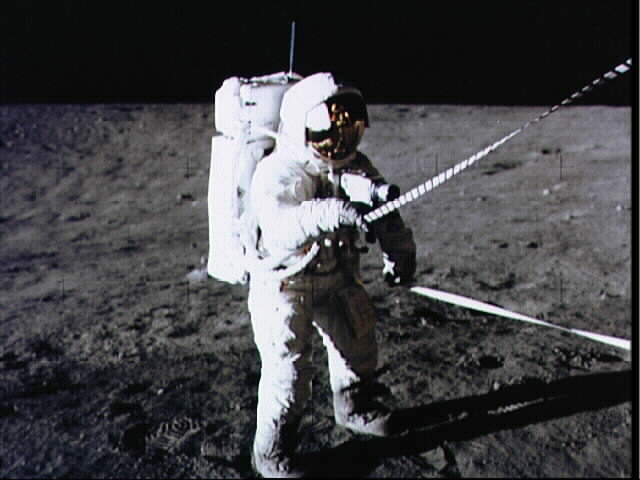

Conrad and astronaut Alan Bean spent seven hours and 45 minutes on the lunar surface. Among their tasks was installing a nuclear power generating station to provide a power source for long-term experiments.

During the 28-day Skylab flight in May-June 1973, Conrad established a personal endurance record for time in space by bringing his total flight time to 1,179 hours and 38 minutes. He called his last mission in space the most satisfying, working to repair the damage Skylab suffered during its liftoff.

After retiring from NASA and the Navy in 1973, he worked as chief operating officer of American Television and Communications Corp. in Denver and later for McDonnell Douglas Corp., the aviation manufacturer.

Among his numerous awards were the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, two NASA Distinguished Service Medals, two NASA Exceptional Service Medals, two Navy Distinguished Service Medals and two Distinguished Flying Crosses. He was enshrined in the Aviation Hall of Fame in 1980.

The Philadelphia native is the third of the 12 original moon walkers to die. James Irwin of Apollo 15 died in 1991 and Alan Shepard of Apollo 14 died a year ago.

In reflecting on the upcoming 30th anniversary of Apollo 11, Conrad recently said, “Time flies when you’re having fun, and I’ve been having fun for the last 30 years.”

Conrad, who divorced his first wife, is survived by his second wife, three sons and seven grandchildren. A son preceded him in death.

Courtesy of the Associated Press

O J A I, California, July 9, 1999 — Charles P. “Pete” Conrad Jr., an American astronaut who was the third man to walk on the moon, died Thursday (July 8, 1999) after a motorcycle accident near Ojai. He was 69.

Conrad was riding his motorcycle with friends when he crashed on a turn, Ventura County Deputy Coroner James Baroni said. Conrad, who lived in Huntington Beach near Los Angeles, died later at an Ojai hospital. As commander of the Apollo 12 mission in 1969, Conrad earned the distinction of being the third man to walk on the moon. Along with astronaut Alan Bean, Conrad spent seven hours and 45 minutes on the lunar surface.

NASA selected Conrad, an aeronautical engineer, as an astronaut in 1962. He was the pilot of the Gemini 5 mission in 1965, which set an endurance record in orbiting the earth. A year later, Conrad commanded Gemini 11, which docked with another craft and featured space walks by another pilot.

Conrad, who was an aviator in the U.S. Navy after graduating from Princeton University, also flew in the first manned Skylab mission, in 1973. During this mission, he established a personal endurance record for time in space, with 1,179 hours and 38 minutes. In an interview with The Associated Press over Memorial Day weekend at Kennedy Space Center, Conrad said he was looking forward to the day he turned 77.

“I fully expect that NASA will send me back to the moon as they treated Sen. [John] Glenn, and if they don’t do otherwise, why, then I’ll have to do it myself,” he declared.

After retiring from NASA and the Navy, he worked as chief operating officer of American Television and Communications in Denver and later for aviation manufacturer McDonnell Douglas. In 1995, he formed his own company called Universal Space Lines and several sister companies with the goal of commercializing space.

“He was going back to space as an entrepreneur, trying to create way s for rockets to launch inexpensively and manage satellites,” said his widow, Nancy Conrad. Conrad is survived by his wife, three sons and seven grandchildren. A son preceded him in death.

Courtesy of The Los Angeles Times:

Charles “Pete” Conrad, the Apollo 12 astronaut who was the third man to set foot on the moon, died Thursday night (July 8, 1999) after losing control of his motorcycle on a mountain road near Ojai, California, authorities said.

Conrad, a Huntington Beach resident whose lifelong aerospace career started with NASA in 1962, died at 5:07 p.m. at Ojai Valley Hospital, five hours after crashing his 1996 Harley-Davidson, said James Baroni, a Ventura County deputy county coroner. Conrad was 69.

Doctors who operated on Conrad to find the source of internal bleeding were unable to revive him, Baroni said.

“Initially it did not appear that he had many injuries,” Baroni said. “But after he was there [at the hospital] for a while, he started having more difficulty breathing and his blood pressure was dropping.”

Conrad’s wife, Nancy Conrad, was riding on another motorcycle when the crash occurred, Baroni said. The couple and several friends, also on motorcycles, had been headed north to Monterey. The group planned to stop at Ojai for lunch, Baroni said.

It was not uncommon for Conrad to be riding. In fact, he was a thrill-seeker. In an interview with The Times several years ago, Conrad said he enjoyed “Fast bikes, fast cars and anything that moves.”

The crash occurred on a slight grade on California 150 about three miles east of Ojai in an unincorporated area of Ventura County. Conrad’s riding buddies, some of whom were bringing up the rear and came upon him seconds after the crash, said it appeared Conrad was traveling under the posted 55 mph speed limit when he took the turn, Baroni said. Conrad, who was wearing a helmet and full riding gear, apparently took the turn wide, lost control and flew off the bike onto the pavement, authorities said. An autopsy is scheduled in Ventura today and funeral arrangements are pending, Baroni said.

Conrad was born June 2, 1930, in Philadelphia. As a child, he built and flew model airplanes. At 15, he swept up scraps in a airfield machine shop to earn flying lessons. In 1946, at 16, he flew solo for the first time. Conrad spent two years at the Darrow School in New Lebanon, New York, before attending Princeton University, where he graduated with a degree in aeronautical engineering and met his first wife, Jane DuBose. They raised four sons before divorcing in 1990. After college, he joined the Navy, became an aviator and attended the Navy Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland, where he served as a test pilot, flight instructor and performance engineer. It was at Patuxent River that Conrad later said he developed “the killer instinct” of a test pilot. Conrad’s career in space began when NASA selected him as part of its second astronaut class in 1962. He and Commander L. Gordon Cooper were launched on the Gemini 5 flight August 21, 1965. Despite mechanical difficulties, near-aborts and physical discomfort, the flight lasted eight days. It was the longest manned space flight to that date. Conrad’s next venture into space travel was the three-day Gemini 11 flight Sept. 18, 1966, which he commanded. The Gemini missions kept pushing the frontier, paving the way for Conrad’s biggest challenge: The Apollo 12 voyage from November 14 to 24, 1969.

It was on that mission that Conrad and astronaut Alan Bean walked on the dusty lunar surface collecting rocks and conducting experiments. In a 1996 interview with The Times, Conrad recalled looking homeward from the lunar surface: “The Earth resembled a beautiful blue marble suspended against a black velvet blanket.” Conrad was later awarded a Space Medal of Honor. He retired from NASA and the Navy in 1973 to enter the business world. He worked at McDonnell Douglas for 20 years before retiring in 1996.

Friends told The Times in 1996 that Conrad always managed to meld knowledge and articulate conversation with stories and humor. They described him as having a zest for learning and exploring.

Over the years, he was involved in projects to get children interested in space. He published spaceman-oriented comic books featuring “Commander Pete,” his cartoon persona. Conrad once said that he had lost friends, test pilots, who were killed on dangerous missions. But he said in his own life no loss had been more painful than the death of son Christopher in 1990 of bone cancer. Conrad is survived by his wife, and three grown children: Peter, Thomas, and Andrew.

Courtesy of The Washington Post

Apollo 12 astronaut Pete Conrad, the third man to walk on the moon and the only one to shout “Whoopee!” as he hopped onto its dusty surface, was killed in a motorcycle accident, leaving life the way he lived it: traveling fast. He was 69.

The fun-loving, irrepressible Conrad crashed his 1996 Harley-Davidson on a curve along a winding mountain road Thursday near Ojai in Southern California and died at a hospital of internal bleeding from chest and abdominal injuries.

Besides Apollo 12 in November 1969, Conrad flew two Gemini missions in the mid-1960s and commanded NASA’s first space station, Skylab, in 1973. He later worked as an aerospace executive and formed a company aimed at making spaceflight as common as a jet ride.

Six weeks ago, in an interview with The Associated Press in advance of this month’s 30th anniversary of the first manned moon landing, by Apollo 11, Conrad said he couldn’t be happier and was looking forward to old age.

“Time flies when you’re having fun, and I’ve been having fun for the last 30 years. I’ve been having fun for a lot longer than that,” said Conrad, who lived in Huntington Beach, California, and went by Pete even though his real name was Charles.

Ever the joker, Conrad couldn’t resist a playful jab at John Glenn, who became the oldest person in space last October: “I am looking forward to when I’m 77. I fully expect that NASA will send me back to the moon as they treated Senator Glenn, and if they don’t do otherwise, why, then I’ll

have to do it myself.”

Flags flew at half-staff at Kennedy Space Center and other NASA installations in observance of Conrad’s death.

“America has lost one of the great aviators and explorers of the 20th century,” NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin said. “He embodied the `can-do’ spirit of NASA, taking on problems and dealing with them without a lot of fuss.”

Apollo 11’s Buzz Aldrin, the second man to walk on the moon, called Conrad a “tireless pioneer … enamored with `pushing the envelope.’ ”

Glenn said that he spoke with Conrad three or four weeks ago and that Conrad was considering buying an executive jet and was excited about it.

“I didn’t know anyone that was filled with more irrepressible enthusiasm and sense of humor and new ideas and general joy of life than Pete,” Glenn said. “He’ll be missed very much.”

Conrad always spoke his mind. To prove that NASA bureaucrats weren’t telling astronauts what to say when they stepped onto the moon, he bet an Italian journalist $500 that he would declare: “That may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a hell of a step for me.”

It was a takeoff on Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong’s line four months earlier, on July 20, 1969: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Once he reached the moon, the 5-foot-6 Conrad cleaned up his language, but the essence remained.

“Whoopee!” Conrad shouted as he descended the ladder of his lunar lander on November 19, 1969. “Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.”

He claimed he never saw the $500.

Howard Benedict, a former Associated Press aerospace writer who is now executive director of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation near Cape Canaveral, said Conrad stood out among the Gemini and Apollo astronauts because of his keen sense of humor.

“He was fun-loving and he always had a smile, that famous gap tooth of his sticking out,” Benedict said. “He always seemed to enjoy life and he also could be very serious.”

Benedict recalled Conrad’s reaction after the Apollo 12 rocket was struck by lightning seconds after liftoff. Most of the electrical power was knocked out but quickly came back on, prompting Conrad to quip that it had looked like a lit-up pinball machine in the cockpit for a while.

Born in Philadelphia, Conrad received a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering from Princeton University in 1953. He then joined the Navy and became a naval aviator. He attended the Navy Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland, and later served there as a test pilot, flight instructor

and performance engineer.

NASA picked him for its second group of astronauts in 1962, three years after the seven original Mercury astronauts were selected.

Conrad served as pilot of Gemini 5 in 1965, flying with Gordon Cooper. He went on to command Gemini 11 in 1966. His crewmate was Dick Gordon.

As commander of Apollo 12, Conrad flew to the moon with Alan Bean and Dick Gordon. Conrad and Bean spent nearly eight hours exploring the lunar surface and 31 1/2 hours on the surface altogether, as Gordon circled the moon in the command module.

The three remained good friends after Apollo 12 — unusual for a space crew — and even called one another on the anniversaries of their flight.

Conrad considered his 28-day Skylab mission the most challenging and satisfying of all because of repairs he and his crew made to salvage the space station, which was crippled during launch.

He retired from NASA and the Navy in 1973.

“The moon didn’t do anything for or against me, didn’t change any of my ideas,” he once said. “I tell you, the most attention I ever got was in 1974 or 1975, right after I retired, when I did one of the original `You don’t know me’ American Express commercials.”

After NASA, Conrad’s passion for space exploration never diminished.

During the mid-1990s, he was flight manager for McDonnell Douglas Corp.’s prototype rocket that took off and landed vertically. NASA passed over it in a competition for a replacement for the space shuttle, instead choosing Lockheed Martin Corp.’s horizontally landing spacecraft.

In 1996, Conrad formed Universal Space Lines Inc. in Newport Beach, Calif., with the hope of making spaceflight available to everyone.

“Forty years after the Wright brothers flew, in 1943, even if we were in the middle of a war, you could go buy an airline ticket, OK? It’s been 41 years now since NASA was formed, and you can’t buy a ticket anywhere in space,” Conrad said. “Commercial space is just barely beginning to be

able to go, but we have wasted 30 bloody years, if you want my take on it.”

Conrad is the third of the 12 moonwalkers to die. Apollo 14’s Alan Shepard died last July following treatment for leukemia. Apollo 15’s Jim Irwin died of a heart attack in 1991.

Conrad is survived by his wife, Nancy, who was riding another motorcycle at the time of the accident; three sons; and seven grandchildren.

Courtesy of The Washington Post:

At 69, he still came across like a kid with a big, mischievous grin. He was a spinner of yarns, a prankster, racing through an active life with a cell phone at one ear and his hand on the controls of some racy vehicle.

Careful not to become trapped in the receding glories of Apollo, Pete Conrad, the third man to set foot on the moon, had kept his life on fast-forward, his focus on the future – until he finally ran out of road hurtling up the California coast Thursday on his Harley-Davidson. It would be sentimental claptrap to suggest that, if he had to go, this is the way he would have wanted it. He didn’t want to go. As a colleague said yesterday, “He took risks, but he wasn’t reckless.” He had too much he wanted to do, much of it in concert with his wife and sidekick, Nancy, another high-energy type. There were kids and grandkids, and he had his own aerospace company to run.

Pete Conrad was one of the most colorful of the early astronauts, one of the most fun to be around, and he was in many ways their minstrel – the man who had an inexhaustible supply of stories about the space age. He became one of the main characters – and was presumably one of the best sources of material – in Tom Wolfe’s epic history, “The Right Stuff.” In the opening scenes, he was a young test pilot at the Patuxent River Naval Air Station, going about the gruesome task of picking up bits and pieces of buddies who have crashed and burned in their jets. By his early thirties, he had established a reputation as a great “stick and rudder” man.

While he always took his work seriously, he wore life like a loose garment. He started riding motorcycles in his teens. He liked to race Formula-V cars. He liked to go fast – but he was not a fool about it. He liked to remember the time in 1964 when he and some friends headed for a Texas ranch three hours away to do some hunting. They formed a parade of Corvettes. Deke Slayton, head of the astronaut office, took the lead. They were doing 100 mph or more on the two-lane road and along the way, he said, “we picked up some poor kid in another Corvette. He was just a teenager who saw us go by and wanted to join the fun.” They were going so fast that even Conrad was concerned, so when they stopped for burgers, he suggested that the quiet, serious Neil Armstrong take the point. That should slow things down, Conrad thought. Instead, Armstrong took off, going faster than Slayton had. Pretty soon, they heard sirens. They all were pulled over and arrested.

Michael Collins, another Apollo astronaut, summed up Conrad this way: “Funny, noisy, colorful, cool, competent; snazzy dresser, race-car driver. One of the few who lives up to the image. Should play Pete Conrad in a Pete Conrad movie.”

Conrad gave his fellow pilots deliberately abusive nicknames, the most famous of which was “Shaky” for Jim Lovell, who would become commander of the nearly tragic Apollo 13 and would be played by Tom Hanks in the hit movie.

Sorely disappointed at not being chosen to be one of the original Mercury astronauts, Conrad speculated that it was because he made sport of the psychologists’ tests. When they showed him a blank card, for example, he stared at it briefly and told them: “It’s upside down.”

Friends say one of Conrad’s finest memorials is a code that would allow astronauts to discuss private matters or say naughty things on the communications loop without outsiders understanding what was going on. And he invented a fictitious astronaut named Walter Frisbee, to whom he referred when talking to reporters. Legend has it that Frisbee was sometimes quoted in print.

He was the sort of man who, as commander of Apollo 12, could sit coolly with his two crew mates as they accelerated toward orbit, realizing that lightning had just struck the fuel-loaded bomb – the giant Saturn 5 moon rocket – atop which they sat. The bolt tripped virtually every circuit breaker on board, but as soon as Conrad was assured the flight did not have to be aborted, he and his crew mates broke out in uproarious laughter. It would make a great war story!

Some Apollo veterans, including Conrad himself, have mused that – for better or worse – the whole tone of the moon landings would have been different if the exuberant Conrad, rather than the taciturn Neil Armstrong, had commanded the first landing.

Conrad provided a sample after his pinpoint landing on the moon, when he took that historic three-foot step from the ladder on November 19, 1969, and became the third man to set foot in the lunar dust. By this time, the United States had won the moon race against the Russians, public scrutiny had relaxed and the need for profundity had diminished.

“Whoopee!” Conrad said as he stepped off, and then, referring to the fact that he was short (5 feet 6): “Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.”

According to an account in “A Man on the Moon,” by Andrew Chaikin, which Conrad recently confirmed in an interview, he said that in order to win a bet. He and his first wife, Jane, had been home in Houston, sitting around the pool with journalist Oriana Fallaci, who was convinced that NASA had scripted Armstrong’s first words on the moon for him. Conrad vowed to prove otherwise by predicting to her at that moment what he would say upon landing. “Impossible,” Fallaci growled. “They’ll never let you get away with it.” Conrad was never able to collect the $500 he won in the bet.

After he left NASA, Conrad devoted his time to developing better ways to get into space, good causes, and fun with friends. He still flew a Cessna Citation business jet. “He loved to be on the cutting edge, no matter where it was,” said 30-year friend, former “Today” show host Jim Hartz.

It was a tenet of the culture of the Right Stuff that one never talked about death or the fear of death. A test pilot always figured if he did everything he was supposed to do, he would never “auger in.”

To the last, Conrad had that to hold on to. There are reports from the scene of the accident that neither Conrad, nor those who were with him, thought his injuries were very serious at first. When he went under the anesthesia, he still thought he’d be coming back.

Charles P. Conrad Portrait Courtesy of NASA

Photo Courtesy of NASA

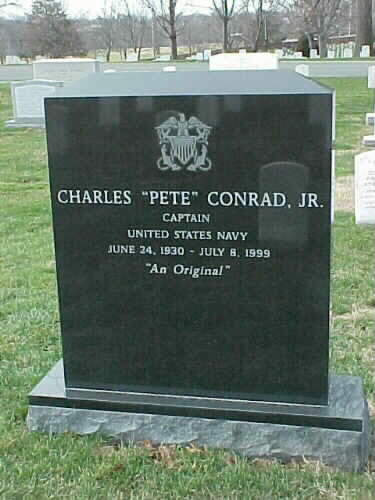

CONRAD, CHARLES JR

CAPT US NAVY

DATE OF BIRTH: 06/02/1930

DATE OF DEATH: 07/08/1999

BURIED AT: SECTION 11 SITE 113-3

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

I was a personal acquaintnce of Captain Conrad (Pete), and left the tribute to him on my website. Shortly after the funeral NASA requested and received my permission to use any or all of the photos from my tribute.

I have just submitted one of my photographs, somewhat touched up with PSP9, to the Photographer’s Workshop.

Having just seen the web page that you have for Pete, I make that offer to you as well.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard