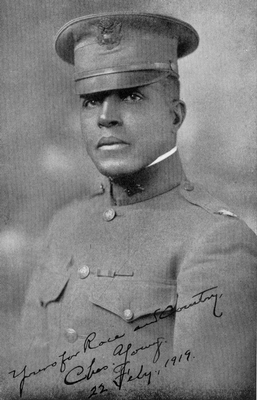

“January 12, 1922 – The passing of a picturesque and interesting figure in U.S. Army life was recorded in a cablegram to the State Department from Monrovia, Liberia, which recorded the death of Colonel Charles Young, formerly of the 10th United States Cavalry, who commanded a squadron in Pershing’s Punitive Expedition into Mexico against Pancho Villa, and the only member of the Negro race to reach the rank of Colonel in the Regular Army. What mission took him to Nigeria and how he met his death has not been reported to the U.S. government.

“While a Major he was in command of a squadron of the famous 10th Cavalry. He and his squadron rode to the relief of Major Tompkins when the latter and his men were ambushed at Parral in an affair that nearly brought the American and Mexican governments to the verge of hostilities. Besides commanding troops in Mexico, he served in the field with Cavalry units as a line officer in the Far West and on two tours of duty in the Philippines.

“A native of Kentucky he graduated with the class of 1889, 49th out of 49 graduates, at West Point, and reached his Majority in 1912. He was retired for physical disability early in World War I, with the rank of Colonel.”

He died on January 8, 1922 and his funeral was one of only a handful in history to be held at the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. He is buried in Section 3 of the cemetery.

Charles Young was born March 12, 1864, in Mayslick, Kentucky, the son of former slaves. His father enlisted as a private in the Fifth Regiment of the Colored Artillery (Heavy) Volunteers. When Young’s parents moved across the river to Ripley, Ohio, he attended the white high school. He graduated at the age of 16 and was the first black to graduate with honors. Following graduation, he taught school in the black high school of Ripley.

While engaged in teaching, he had an opportunity to enter a competitive examination for appointment as a cadet at West Point. Young was successful, making the second highest score, and in 1883 reported to the military academy. Young graduated with his commission, the third black man to do so at that time. He was assigned to the Tenth and the Seventh Cavalry where he was promoted to first lieutenant. His subsequent service of 28 years was with black troops — the Twenty-fifth U.S. Infantry and the Ninth U.S. Cavalry.

In 1903 Young served as captain of a black company at the Presidio, San Francisco. He was appointed acting superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant national parks, thus becoming the first black superintendent of a national park. He was responsible for the supervision of payroll accounts and directed the activities of rangers. Young’s greatest impact on the park was road construction that helped to improve the underdeveloped park.

Due to his work ethic and perseverance, Young and his troops accomplished more that summer than the three military officers who had been assigned the previous three years. Captain Young and his troops completed a wagon road to the Giant Forest, home of the world’s largest trees, and a road to the base of the famous Moro Rock. By mid-August, wagons of visitors were entering the mountaintop forest for the first time.

Young was transferred on November 2, 1903, and reassigned as troop commander at the Presidio. In his report to the secretary of the interior, he recommended the government acquire patented lands in the park. This recommendation was mentioned in legislation introduced in the House of Representatives. The Visalia, California, Board of Trade showed appreciation of his performance as the park’s acting superintendent by presenting him with a citation.

On other military assignments, Young continued to persevere in a world of obstacles in his path. He attained the rank of lieutenant colonel, the first black to do so in the U.S. Army. He died in 1922, while detailed in Nigeria. Colonel Young was given a hero’s burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

In both military and civilian activities, Young demonstrated qualities of character during a time when prejudice was a way of life. As mentioned in the 53rd Annual Report of the Association of West Point Graduates, “. . . in all his relations with society, both as a citizen and soldier, his constructive influence with his people was ever a potent factor along the troublous highway of enlightened progress.”

Black officer built an Army career only to become a victim of bigotry

22 Febriary 2004

By Elizabeth Sullivan

Cleveland Plain Dealer Staff Writer

The vast sweep of history often masks the small dramas that define it. Such is the case with Colonel Charles Young, a now-obscure American military officer whose brilliant career-against- the-odds 100 years ago spanned the era from slavery to empire. His story illuminates the best and worst of this time, when men such as himself, who were born into slavery and rose to prominence in every field, were denied their rightful places in an America beginning to flex its muscles in the world.

Young’s career was glittering but unfulfilled. With a general’s star in grasp, bigotry ended his advancement as surely as a bullet would have. The nation that deemed Young too sick to serve in World War I sent him on a military intelligence assignment to Liberia as soon as the war was over. It was a mission his closest friends knew he wouldn’t survive. Young died in Nigeria in 1922, leaving his wife and two kids to scrape by in southern Ohio by selling much of their property. The justifiable outcry from black America meant Young was buried at Arlington National Cemetery the following year. But soon his exceptional career and contributions were forgotten.

Young today is not nearly as well known as other pioneering black military figures, including Henry O. Flipper, the first black to graduate from West Point, who was drummed out of the service in 1882 on questionable charges that President Bill Clinton pardoned in 1999, and Benjamin O. Davis, America’s first black general. Yet it was Young who spanned the era between these two men, who had the lifelong military career that Flipper was denied and who kept the possibilities alive for all who followed, including Davis, one of many black soldiers he mentored.

One of the problems in writing about Young has been the lack of a coherent, comprehensive archive. His personal papers were scattered after relatives auctioned off many items 23 years ago when the family home in Wilberforce was sold. Most of his Army file had gone up in smoke in a 1973 St. Louis fire, while his pioneering military intelligence studies from Haiti were largely destroyed in a State Department housecleaning in the 1920s.

Now, thanks to the dogged research skills and vision of a talented young historian in West Virginia, a just-published biography fills the gaps, plus some. While not precisely a page-turner, David Kilroy’s book, “For Race and Country,” is well-written, fast-paced, positively dripping with new information, yet economical of word.

More importantly, Kilroy, an associate professor of history at Wheeling Jesuit University, pieces together a readable story out of the most far-flung bits of evidence. Kilroy also has found the mother lode that eluded earlier researchers: A private collection in Akron holds the bulk of Colonel Young’s posthumously auctioned personal papers, including diary entries, letters and even musical scores, as well as the biographical contributions of Young’s wife and son.

The book is copiously footnoted, but apart from an awkward construct in which each chapter opens with a summary of itself, the scholarly dressing doesn’t appreciably slow this tale. In fact, Kilroy hoped to have his first book rated as general nonfiction. No such luck. The “academic” tag it carries reflects in the forbidding all- black cover and an eye-popping suggested retail price of $67.95.

That’s too bad. Young’s story deserves the widest possible telling. The injustice done him should not be forgotten.

Through pioneering military intelligence work in Haiti and Liberia, and combat in the Philippines and Mexico, Young directly contributed to the beginnings of the American empire. Likewise, through his dedication to race and his conviction that the “talented tenth” of black America could pull up not only other blacks, but also blacks throughout the world, Young contributed to a renaissance in American cultural life. His military, literary and anthropological studies all show a prescient sense of how small the world really is.

Sadly, these accomplishments, patriotism and self-sacrifice were for naught. On the eve of U.S. entry into World War I, Young was forced into retirement by a White House that would not accept the possibility of a black Army general, and so it made sure he was out of commission for the duration of the war.

Young had managed to overcome years of slights and discrimination through the sheer power of his good humor, charm, talent and dedication to country. But he could not prevail over the racism of an American president, Woodrow Wilson.

At first, Young, who in 1917 was fresh from a field promotion to lieutenant colonel during action against Pancho Villa’s forces in Mexico, couldn’t believe that he was being thrown “on the scrap heap of the U.S. Army,” as he later put it in a bitter letter to a young Cincinnati man contemplating a military career. He ached to serve his country. And for many, many months, he still thought he would be able to. The reality was crushing.

Young died with his boots on, but it was not the just finish to his exemplary life that he deserved. It is a life that comes alive again in Kilroy’s 183 pages.

Sullivan is an associate editor for The Plain Dealer’s editorial pages.

To reach her: books@plaind.com

Black officer’s park role honored 100 years later

By Fahizah Alim

Courtesy of the Sacramento Bee

5 March 2004

The massive trees of Sequoia National Park are so imposing and impressive that over the years, people have been compelled to give them names. These giants – the largest sequoia is more than 100 feet in circumference at the base and 275 feet tall – are named after great generals, national organizations, even a president.

Thanks to the efforts of a Sacramento man, this summer another massive sequoia will be named after an eminent American: Colonel Charles Young, the son of slaves who became the first African American to become the superintendent of a national park.

In 1903, Young, then a captain leading the U.S. Army’s all-black 9th Cavalry – the famed “buffalo soldiers” – played a critical role in helping preserve the groves of Sequoia and making them accessible to the millions of people who visit the park in the southern Sierra Nevada each year.

Until recently, the contributions of Young, who in 1889 became only the third African American to graduate with a commission from West Point, had been largely overlooked. That has changed thanks to George Palmer, who began a letter-writing campaign to gain Young a place in history books.

“It’s important to know about this man,” Palmer says, “not only because of his service to this country and his role in the development of this park, but also because his environmental attitude was far ahead of his time.”

Palmer, a retired San Francisco sheriff’s captain who moved to Sacramento three years ago, says Young’s legacy deserves to be preserved.

“When I found out about the contributions that Colonel Young had made, I couldn’t allow them to continue to be ignored,” he says.

“One of my former teachers told me, ‘If they haven’t recognized him in 100 years, what makes you think they are going to do it now?’ I said, ‘Because I’m not going to quit until it’s done.'”

Longtime park enthusiasts, Palmer and his wife have visited a national park or a national monument every year since 1969.

In 1997, Palmer was volunteering as a docent at Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park north of Bakersfield, which preserves the only California town to be founded, financed and governed by African Americans.

A teacher visiting the site asked Palmer why a street in the state park was named after Charles Young. Who was he?

“I had to sheepishly admit that I didn’t know,” Palmer recalls.

In an encyclopedia, Palmer found a small item about Young that placed him at West Point and mentioned that he had a role at some national park, but not which one, Palmer says.

He did more research on Young in a Visalia library. He learned that in 1903, Young had been superintendent of Sequoia National Park.

“I drove to Sequoia to see what I could find out,” Palmer says. “I found that he had finished the road into the Giant Forest and built the road to Moro Rock. He put the first protective fence around the General Sherman Tree and the General Grant Tree.

“But when I visited the park, it had no recognition in its museum of what Colonel Young had contributed,” he says.

Starting in 1998, Palmer wrote letters to politicians and others requesting that funds be provided to give recognition to Young and the 9th Cavalry for the work they performed.

Both President Clinton and Senator Diane Feinstein responded to his letters and said they had forwarded his requests to the National Park Service for investigation.

However, it wasn’t until President Bush visited the park in 2001 that things started moving.

“I wrote him a three-page letter telling him what he didn’t see when he had visited the park,” Palmer says. “Nine months later, I got a letter from the National Park Service, inviting me to sit down with them and help plan the centennial celebration.”

Finally, in August 2003, 100 years after Young and his buffalo soldiers rode into Sequoia National Park, the park service unveiled a mural honoring Young and the 9th Cavalry.

A ceremony was also held to rededicate a tree that Young had named for African American educator Booker T. Washington during the summer of 1903. Eighteen of Washington’s descendants and 11 of Young’s descendants were on hand for the festivities, which included re-enactments of buffalo soldier camps and activities. Donald Murphy, deputy director of the National Park Service, was among the keynote speakers.

So was William Tweed, chief naturalist for Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks.

“In one summer, Young and his black soldiers succeeded in accomplishing more work in the park than had been done in the three years prior,” Tweed says.

“From 1891 to 1913, troops of soldiers came to protect the park during the summer,” he says. “But the most significant year was 1903.”

In addition to opening the parks to public use, Tweed says, the troops focused on resource protection. They curtailed illegal grazing in the mountain meadows. Recognizing the damage being done to the sequoias by the trampling of tourists’ feet, they put the first fences around the most-abused trees.

“What makes 1903 stand out is not only that so much was accomplished, but also … that it was accomplished by buffalo soldiers under Captain Young. … Everything Young did in life was to show people what African Americans could accomplish,” Tweed says.

Palmer’s research found that Young’s contributions extended far beyond his summer assignment in the Sierra.

During his 37 years of military service, Young served in the Philippines, Haiti, Liberia and Mexico. He died on a military mission in Nigeria and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Clearly, Young believed America was worth fighting for and its beauty worth preserving, Palmer says.

Young’s strong advocacy was evident from his comments in his final official report upon completing his stint at Sequoia National Park:

“Indeed a journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are.”

Courtesy of Buffalo Soldiers:

Colonel Charles Young is remembered and honored as a man of unique courage and inspiration. This was especially true for those of “goodwill”, who knew him, and for those who followed him into battle. He stands honored both as an African-American and in the history of African-Americans in the U.S. military.

Young was born March 12, 1864 to exslaves in the little hamlet of MaysLick, Kentucky. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1889. This gave him the honor of being the third African-American to do so, in spite of the hatred, bigotry and discrimination he encountered as an undergraduate.

His first assignment after graduation was with the Buffalo Soldiers in the 10th Cavalry in Nebraska, and then in the 9th and 10th Cavalries in Utah. With the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, he was reassigned as Second Lieutenant to training duty at Camp Algers, Virginia.

Young was then awarded a commission as a Major in the Ninth Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Later, during the Spanish-American War, he was in command of a squadron of the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers in Cuba.

After the war with Spain, Young was reassigned to Fort Duchesne in Utah where he successfully arbitrated a dispute between Native Americans and sheep herders. He also met one of the many soldiers who would eventually benefit from his encouragement, Sergeant Major Benjamin O. Davis. Later, Davis would became General Benjamin O. Davis, the first African-American to reach the rank of General in the U.S. army.

Charles Young distinguished himself throughout his military career with the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th Cavalries, and the 25th Infantry. He also served as Professor of Military Science at Wilberforce University, Ohio.

With the creation of the army’s Military Information Division (MID), came his assignment as one of the army’s first military attachés, in Port Au Prince, Haiti. His job was to observe the training and exercises of foreign armies and make reports on their relative strengths and weaknesses. United States intelligence was desperate for new maps and information about groups struggling for political power in Haiti. Young risked his life to fulfill his assignments, only to have his maps and reports stolen and sold to the Haitian government.

In 1903 Captain Young was in command of the 10th Cavalry, who were segregated at the Presidio of San Francisco. He was assigned “Acting Superintendent” of Sequoia National Parks in California for the summer. The management of the park was the responsibility of the army, which had very little Congressional funding. This problem and the fact that no “Acting Superintendent” of Sequoia National Parks ever stayed at this assignment for more than two consecutive summers resulted in the construction of less than five miles of roads within the park. The lack of a wagon road severely limited the number for people who visited the Giant Forest of Redwoods, which are the largest trees in the world.

Young and his troopers arrived in Sequoia after a 16-day ride. Their first priority was the extension of the wagon road. As always, Young’s aggressive style of leadership, produced results. A road longer than all previous roads combined was produced, ending at the base of Moro Rock. This opened up the park to a the public who was clamoring to experience Sequoia National Parks. Soon wagons and automobiles were winding their way to the mountain-top forest for the first time.

Young was sent to the Philippines to join his 9th regiment and command a squadron of two troops in 1908. Four years later he was once again selected for Military Attaché duty, this time to Liberia. For his service as adviser to the Liberian Government and his supervision of the building of the country’s infrastructure, he was awarded the Springarn Medal, an award that annually recognized the African-American who had made the highest achievement during the year in any field of honorable human endeavor.

During the 1916 Pershing’s Punitive Expedition into Mexico, Young was praised for his leadership in the pursuit of the bandit Pancho Villa, who had murdered American citizens. Commanding a squadron of the 10th United States Cavalry, he led a cavalry pistol charge against the Villista forces, routing the opposing forces without losing a single man. The swift action saved the wounded General Beltran and his men, who had been outflanked.

On another occasion, Young was credited with averting disaster when he and his men came to the relief of the 13th U.S. Cavalry squadron who were fighting a heavy rear guard action.

Because of his exceptional leadership of the 10th Cavalry in the Mexican theater of war, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and was briefly Fort Huachuca’s commander in Texas.

Young was devoted to his wife Ada and their two children; son, Charles Jr. and daughter Marie. He was sure to have played the piano, and at least a few of his compositions, when he was home between assignments. Being versatile, he also played the violin and guitar. Linguistically, he spoke several languages.

Colonel Charles Young was the highest ranking African-American officer in the army when WW1 started. He was also the first African-American to reach that rank in the army.

With the explosive arrival of WW1, the public, and especially African-Americans considered the possibility of Young receiving a major leadership role in the war. He had met challenges of racism, bigotry, and discrimination embedded within society and within the military. He had shown himself to be exceptional, not only as an military officer, but also as a leader of men.

But justice and the rule of equality in the military were not for Lt. Colonel Charles Young. When he took his scheduled army physical, the doctors said his blood pressure was too high. Young and his comrades, his supporters, and the African-American news media believed otherwise. On June 22, 1917, Young was retired, under protest.

On a day in June, 1918 retired Lt. Colonel Charles Young, made his way on horseback, 500 miles from Wilberforce, Ohio to this nation’s capital, to show he was as always, fit for duty. There, he petitioned the Secretary of War (now called Secretary of Defense) for immediate reinstatement and command of a combat unit in Europe. The ride from Ohio to Washington D.C. brought bittersweet results. Young was reinstated and promoted to full Colonel, but he was assigned to duty at Camp Grant, Illinois. By the time his reinstatement and promotion were in effect the war was near its end.

Too weak to command in France they said, but not too weak to traverse and suffer the swamps of West Africa, Colonel Charles Young, was once again, assigned to Liberia as Military Attaché. He died at that post on January 8, 1922, while on a research expedition in Lagos, Nigeria.

Colonel Charles Young’s funeral service was one of the few ever held at the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. He is buried in Section 3 of the cemetery.

Today, Colonel Charles Young’s home is scheduled to become the future site of the National Museum of African American Military History. Its unique history relives the days when it was a way station for the Underground Railroad.

NEGRO OFFICER BURIED

Body of Colonel Young Placed in Arlington With Military Honors

WASHINGTON, June 1, 1923 – The body of Colonel Charles Young, the only negro officer ever to reach that rank in the United States Regular Army, was buried in Arlington National Cemetery today with military honors. He died more than a year ago while on duty as Military Attache to the Liberian Republic and the body was temporarily interred at that time.

Services were held at Arlington in the Memorial Amphitheater, which had not been used for a like service of an individual officer or man since the burial of America’s Unknown Dead. The Negro population of Washington made the occasion of Colonel Young’s funeral one of demonstration in respect for his memory, Negro school being closed for the day, and thousands gathered along Pennsylvania Avenue and at Arlington. Many veterans’ organizations one the Negro High School Cadets participated in the funeral parades.

Colonel Young was born in Kentucky and appointed to the Military Academy from Ohio. He serves successively through various grades in the Tenth Cavalry, Thirty-Fifth Infantry, Ninth Cavalry and finally reaching the rank of Lieutenant Colonel on active service to be retired as a Colonel. He served as a Major of the Ninth Ohio Infantry during the Spanish War.

YOUNG, CHARLES

- COL US ARMY

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/08/1922

- BURIED AT: SECTION 3 SITE 1730-B

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard