Wednesday, June 28, 2000

Courtesy of the Boston Herald

Local, state and national veterans representatives are expected to attend a hero’s funeral tomorrow for Charles A. MacGillivary, who earned the Medal of Honor for saving his unit in the Battle of the Bulge during World War II.

Tom Lyons, executive director of the Homeless Veterans Shelter in Boston, said,”`Given Charlie’s reputation, I can’t see it being nothing short of a complete representation of all the veterans organizations in the state.

“It should be a heck of a showing to Charlie for what he did for veterans and his country,” Lyons added.

MacGillivary, 83, who lost his left arm in France when he earned the nation’s highest honor, died Saturday in the VA Hospital in Jamaica Plain. He had lived in Braintree for the past 43 years.

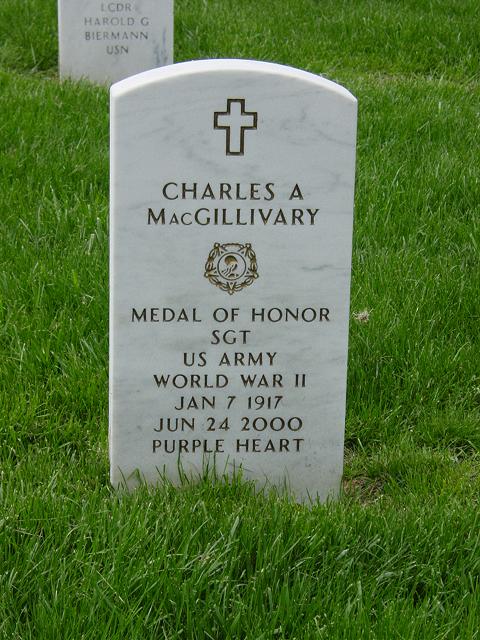

State Veterans Commissioner Thomas Kelley said MacGillivary’s burial will be planned at a date to be named later in a resting place for heroes at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

“I’m sure there will be a number of other Medal of Honor winners there along with federal and state dignitaries,” said Kelley, himself a recipient of the medal. The Bay State’s other living Medal of Honor recipient and former State Veterans Commissioner Thomas Hudner is expected to attend tomorrow’s 10 a.m. Mass at St. Francis Church in Braintree. He could not be reached for comment yesterday.

Governor Paul Cellucci will be in attendance at the funeral.

MacGillivary was waked yesterday afternoon and evening and will also be waked today from 2 to 4 and 7 to 9 p.m., in the Keohame Funeral Home in Quincy.

MacGillivary earned the Medal of Honor Jan. 1, 1945, when his unit was surrounded by an elite SS Panzer Division in Woelfling, France.

MacGillivary, then 27, picked up a machine gun and knocked out four German machine gun nests, killing 36 Nazi soldiers.

After he returned from the war, MacGillivary worked tirelessly for veterans causes. Lyons said, “Over the years, Charlie was a mentor to young veterans like myself and he would show us how to work the system.

“He was someone I could rely on for advice and experience,” Lyons said.

Charles Andrew MacGillivary died on 24 June 2000 at the Brockton, Massachusetts VA Medical Facility. He is to be buried beside his wife, Esther, in Section 48 (grave 568) of Arlington National Cemetery, 13 July 2000.

Friday, June 30, 2000

Courtesy of the Boston Herald

Charles MacGillivary, who lost an arm on a French battlefield during the Battle of the Bulge, was praised yesterday during his funeral Mass in Braintree as being “just what a Medal of Honor recipient should be.”

“He was a great patriot,” said William Wilson, commander of Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 299 in Cambridge.

“A lot of people drove here from everywhere, just because of the decency of

this man,” he said.

MacGillivary, 83, of Braintree died Saturday in the VA Hospital in Jamaica Plain, after a lengthy battle with cancer.

On January 1, 1945, MacGillivary single-handedly killed 36 SS troops and saved his unit from capture or death. He lost his left arm in the process.

His fellow veterans turned out yesterday to help fill St. Francis of Assisi Church for his funeral. The old soldier will be buried with full military honors on July 13 in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

The Rev. Philip Salois, who received a Silver Star during the Vietnam War, told the throng that MacGillivary’s service continued through his entire life.

“Charlie did not let his injury keep him from living a full life and people looked up to him,” Salois said. “He became the hope of the disabled veterans and was a beacon of light for many veterans.”

“Charlie gave of himself and he gave selflessly to the homeless veterans and never stopped giving.”

MacGillivary’s wife, Esther, died last year and the couple had three daughters.

He worked as a special agent for the city of Boston’s Treasury Department and later for the Customs Department, retiring in 1975.

At the end of the service, his granddaughter, Charlene Carmichael, told the mourners, “Charlie was the most generous man I have ever known and he has impacted so many lives with his support and kindness.”

She said her grandfather was a man “determined, diligent” and especially patient.

“If you ever have seen a man with one arm put swimmies (trunks) on a 7-year-old who wants nothing more than to be in the pool, then you have seen a man with endless patience,” she said.

Medal of Honor Citation:

Rank and organization: Sergeant, U.S. Army, Company I, 71st Infantry, 44th Infantry Division.

Place and date: Near Woelfling, France, 1 January 1945.

Entered service at: Boston, Massachusetts.

Birth: Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada.

General Orders Number: 77, 10 September 1945.

He led a squad when his unit moved forward in darkness to meet the threat of a breakthrough by elements of the 17th German Panzer Grenadier Division. Assigned to protect the left flank, he discovered hostile troops digging in. As he reported this information, several German machineguns opened fire, stopping the American advance.

Knowing the position of the enemy, Sergeant MacGillivary volunteered to knock out one of the guns while another company closed in from the right to assault the remaining strong points. He circled from the left through woods and snow, carefully worked his way to the emplacement and shot the two camouflaged gunners at a range of three feet as other enemy forces withdrew.

Early in the afternoon of the same day, Sergeant MacGillivary was dispatched on reconnaissance and found that Company I was being opposed by about 6 machineguns reinforcing a company of fanatically fighting Germans. His unit began an attack but was pinned down by furious automatic and small arms fire. With a clear idea of where the enemy guns were placed, he voluntarily embarked on a lone combat patrol.

Skillfully taking advantage of all available cover, he stalked the enemy, reached a hostile machinegun and blasted its crew with a grenade. He picked up a submachine gun from the battlefield and pressed on to within 10 yards of another machinegun, where the enemy crew discovered him and feverishly tried to swing their weapon into line to cut him down. He charged ahead, jumped into the midst of the Germans and killed them with several bursts. Without hesitation, he moved on to still another machinegun, creeping, crawling, and rushing from tree to tree, until close enough to toss a grenade into the emplacement and close with its defenders. He dispatched this crew also, but was himself seriously wounded.

Through his indomitable fighting spirit, great initiative, and utter disregard for personal safety in the face of powerful enemy resistance, Sergeant MacGillivary destroyed four hostile machineguns and immeasurably helped his company to continue on its mission with minimum casualties.

Sergeant Charles A. MacGillivary, Customs Special Agent, Congressional Medal of Honor Recipient

He wasn’t American by birth. He’d come to the States when he was 16, from Prince Edward Island, Canada, to live with his older brother in Boston. When Pearl Harbor was bombed, he decided the right thing to do was to volunteer for the army of his adopted country. As he told the United States Senate Subcommittee on Immigration 50 years later, when he was in boot camp in Massachusetts, “an officer asked me and two other immigrants … whether we wanted to become U.S. citizens. [They took us] to a federal courthouse and [swore us] in before a judge. I thought that if I was going to fight for this country, I should be a U.S. citizen.”

The path to Woelfling, France

He landed at Omaha Beach, Saving Private Ryan’s beach, in 1944. From there, “we fought our way through France, taking back towns from the Germans,” and finally reaching the town of Woelfling, a village so tiny it isn’t even on the map, by December of that year. It was, recalled one soldier, the coldest, snowiest winter in memory, with Allied soldiers out-manned and out-gunned by eight German Panzer divisions, 13 German infantry divisions, more than 600 light, medium, and heavy guns and howitzers, and 340 multiple-rocket launchers, all trained on American positions.

It was the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last-ditch attempt to salvage a war he was by then clearly losing.

On New Year’s Day 1945, Sergeant MacGillivary’s company, pinned down in that European permafrost by a Panzer division, running out of ammunition and talking of surrender, lost its commander. MacGillivary was next in line to take his place.

He had been assigned to protect his company’s left flank, so he knew precisely where the enemy’s guns were; he also knew his men were surrounded by nests of vipers armed with machine and submachine guns. When several German machine guns opened fire to stop an American advance, MacGillivary volunteered for a lone combat patrol to knock out the guns menacing his troops.

Circling through woods and snow, he managed to shoot two camouflaged German gunners from three feet way as other German forces withdrew. Later that day, he found his company facing yet another hive of at least six machine guns buttressing a company of German soldiers who clearly meant not to be stopped. They began to drench MacGillivary’s unit in a flood of automatic and small-arms fire. Taking advantage of available cover and armed with two machine guns — his own and another he’d picked up from the battlefield — he stalked the enemy.

Perhaps only a soldier knows what fortifies a hero in battle, but whatever it is, it pushed MacGillivary onward as he hurled grenades and killed or wounded German soldiers defending their positions. Ultimately, single-handedly, he took out four German machine-gun emplacements.

At the last emplacement, a wounded German soldier tried to retaliate with his own machine-gun fire and hit MacGillivary in the left side. Almost simultaneously, MacGillivary fired back and killed the man. Then, as MacGillivary recalled for a Boston Globe reporter in 1995, “I looked down and my right arm wasn’t there.

“When you get hit by a machine gun, it’s like somebody put a hot poker in you.” Those permafrost conditions that had made fighting so treacherous also saved his life. “I stuck the stump of my arm into the snow, but the warm blood melted the snow. I figured I was dying. When they rescued me, my arm had a cake of bloody ice frozen around it, sealing the wound. If it had been summer, I’d [have been] dead.”

U.S. Customs, privileged beneficiary

A man can work a lifetime and not achieve the glory, accomplishments, or recognition that Charles MacGillivary did before he turned thirty. Nonetheless, honor in battle had not exactly been a career choice, and once the war ended, he had to make a living.

He returned home to Boston, where he worked briefly as a special agent for the Treasury Department. He joined the Customs Service in 1950, starting as a warehouse officer, but soon went on to become a special agent for what is now the Office of Investigations, conducting investigations in several areas of interest to Customs. An old friend, Bernard Crowley, who knew Charlie from their early days and who retired as chief inspector at Logan Airport, remembers his friend as a gentle, patient, humble man who took great pride in his service with Customs and was highly regarded by his co-workers. His daughter Charlene Corea recently remembered him as being particularly busy in the winter inspecting Christmas trees that entered the country from Canada (and who better to do that?). He retired from the Customs Service in 1975.

Charlie MacGillivary died Saturday, June 24, at the age of 83. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in a funeral reserved for only military heroes: His flag-draped casket was borne to the gravesite by a horse-drawn caisson accompanied by a military honor guard and followed by five older men in business suits, each wearing his own Congressional Medal of Honor. Young solders folded the flag, gave a 19-gun salute, and played Taps.

More than 500 years ago, Shakespeare wrote of a beloved fallen king, “He was a man, take him for all in all, [we] shall not look upon his like again.”

And so it is for those referred to as “the greatest generation.”

And so it is for Sergeant Charlie MacGillivary.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard