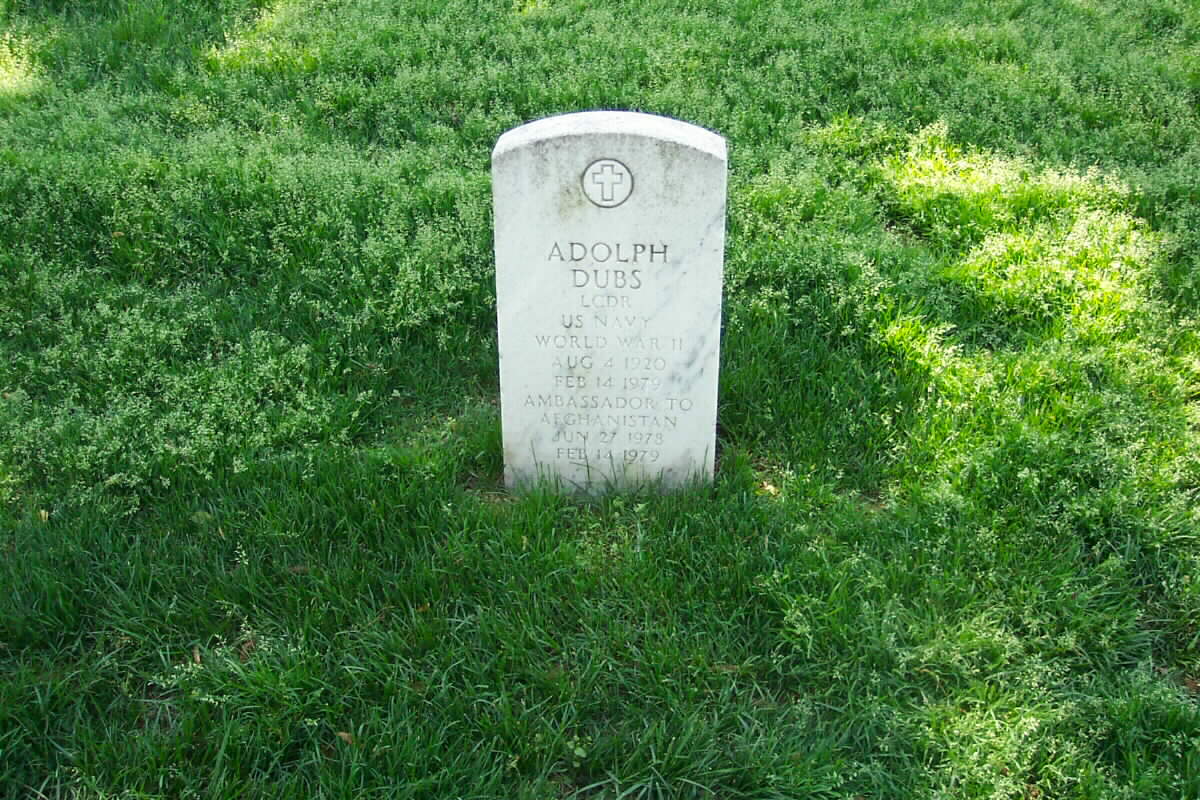

Adolph Dubs (1920-1979) of Maryland. Born in Chicago, Illinois, August 4, 1920. Served in the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II; U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, 1978-79. Assassinated in Afghanistan, February 14, 1979. Interment at Arlington National Cemetery.

Adolph Dubs, the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, was killed in an exchange of gunfire between Islamic extremists who kidnapped him and Afghan security forces.

A top expert in Soviet affairs, Adolph Dubs, was sent out as the U.S. Ambassador on the basis of business as usual. Within months Dubs died in a hail of gunfire from Afghan troops, under Soviet advisers, as they sought to ‘rescue’ him from four kidnappers in a Kabul hotel room. His death merited a weak protest, and the start of the phasing out of the already stagnant U.S. aid program. Nine years later another ambassador was to die violently in suspicious circumstances, again with possible Soviet involvement. This time the reaction was a cover-up.

Assassination of an Ambassador – Afghanistan, 1979

Valentine’s Day 1979 dawned clear and cold for members of U.S. Embassy Kabul. And, as we would see soon enough, it would be a day like no other in our careers. As Press Attache for USIS, I had worked with PAO Roger Lydon and Ambassador Adolph “Spike” Dubs since my arrival in June 1978 to present official U.S. policy to the various ministries of the Marxist-led Afghan government and to help American journalists seeking access to Afghan officials.

Shortly after 8 that morning, Ambassador Dubs, 56, a career FSO, was on his way to the embassy in his bullet-proof vehicle, when men dressed as Afghan police stopped it near the USIS compound. Using a ruse, the armed men persuaded the driver to open his window, forced their way into the car and drove the Ambassador to Kabul Hotel in the city’s center, where they took him hostage in an upper-floor room. The U.S. Embassy driver returned to the embassy to announce the kidnapping.

A stand-off ensued until shortly after noon. Just as U.S. officials believed they had persuaded Afghan Interior Ministry officials not to storm the room, at about 12:30 p.m. a gunshot was heard. Police in the hotel corridor and on rooftops across the street opened up a fusillade into the room that lasted more than a minute. Afterward, silence. Later, Ambassador Dubs was found dead, his body ridden with bullets. None of us at the embassy knew what this event portended or whether it was the beginning of a coup against the government of President Mohammed Tariki, the nominal head of the Khalq Party, a pro-Moscow Marxist organization competing with the rival Parcham organization for control of the Afghan government.

Earlier that morning, when Lydon returned to USIS with news of the Ambassador’s kidnapping, I decided to make an audio record of embassy radio transmissions, using a two-way radio on the embassy’s frequency to monitor and tape transmissions among Kabul Hotel colleagues, and staff at the embassy and in vehicles moving between these locations and the Interior Ministry, where the Afghan government was trying to manage the crisis. Transmission quality varied, but they helped embassy security officers construct a chronology of events for analysis in Washington.

In the hours and days that followed, I worked with Chargé d’Affaires Bruce Amstutz, Political Counselor Bruce Flatin, Public Affairs Counselor Roger Lydon and other embassy colleagues in preparing responses to journalists from the United States, Europe, South Asia and elsewhere. Within 24 hours after the killing, dozens of western journalists had poured into the city and wanted to know what impact the killing would have on U.S.-Afghan relations. I was impressed at the intensity of interest in America about our crisis in Kabul.

It would have been easy for us to hint at links between Soviet KGB and Afghan Interior Ministry officials, but we had to remain absolutely disciplined about information released to the media and the public. The truth was that we had very few hard facts. Any public speculation by embassy officials could have precipitated more dangerous developments in a country whose Marxist-led government was already worried about its survival. The chief responsibility of our embassy was to safeguard the lives of the more than 4,000 Americans living in the country and, especially, those in Kabul.

The kidnapping and murder of Ambassador Dubs remained a mystery for years. We did not know who the hostage takers were, even though three had been taken alive, or what organization they represented, and apparently neither did the Afghan government. The kidnappers had been demanding the release of prisoners who the Minister of Interior claimed were not even in the country.

Through the traumatic days and weeks after the killing, the embassy staff and the international community pulled together. We Americans demonstrated that our mission would not be deterred from its responsibilities to represent our government and our nation in this geostrategically important country. In a simple ceremony in the embassy compound we later honored our fallen ambassador, remembered as a U.S. Marine who had survived the bloody battles of the Pacific in World War II.

As in similar events in other U.S. diplomatic missions – Khartoum, Beirut and Islamabad, to name three – FSOs and their families stood firm in the face of terror and violence and represented the best ideals and values our country offers in the oft dangerous field of international diplomacy. For those who served in Kabul, this is our tribute to “Spike” Dubs.

Bruce K. Byers was USIS Press Attaché at U.S. Embassy Kabul from 1978-79. Byers, who joined the Foreign Service in 1971, also has served in Tehran, Iran; Bombay, India; Vienna, Austria; Bonn, Germany; Washington, D.C.; and Warsaw, Poland.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard