He served on various vessels, including the USS Charleston in Commodore George Dewey’s fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War, and by 1905 had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Commander.

He was promoted to Commander in 1911 and took command of the USS Chester in late 1913. He was aboard it, in Admiral Henry T. Mayo’s Division, when the Tampico Incident occurred on April 9, 1914, and he took part in the occupation of Vera Cruz, Mexico, that followed on April 21-22, winning the Medal of Honor for a daring and unguided night entry into the inner harbor to land a force of Marines and Seamen.

In 1914-18, he commanded Great Lakes Naval Training Center and the 9th, 10th, and 11th Naval Districts, receiving promotion to Captain in August 1916. During 1918-21, he commanded the USS Mississippi and in March 1921 was appointed Director of Naval Aviation with the temporary rank of Rear Admiral (made permanent in 1923).

Too old for flight training, he had qualified in June 1921 as an aerial observer and the creation of the Navy’s Aviation Bureau owes much to his influence. He organized the Navy’s aviation program, exterted influence for the expansion and experimentation, oversaw the selection of sites and building of Naval air stations and accomplished the installation of aircraft landing catapults on all battleships and cruisers of the Fleet.

He was particularly enthusiastic about the use of dirigibles, both in Naval operations and more generally, secured for the Navy the airships Los Angeles, Akron and Macon. He was reappointed to head the Bureau in 1925 and again in 1929.

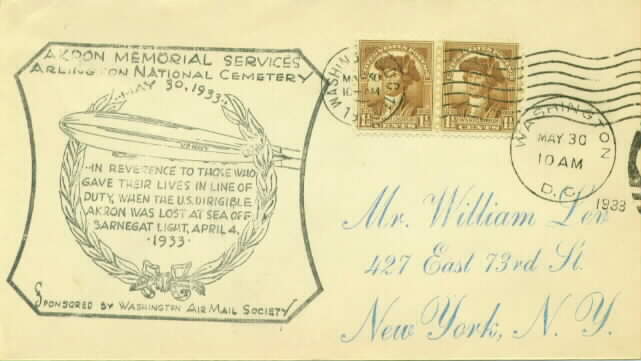

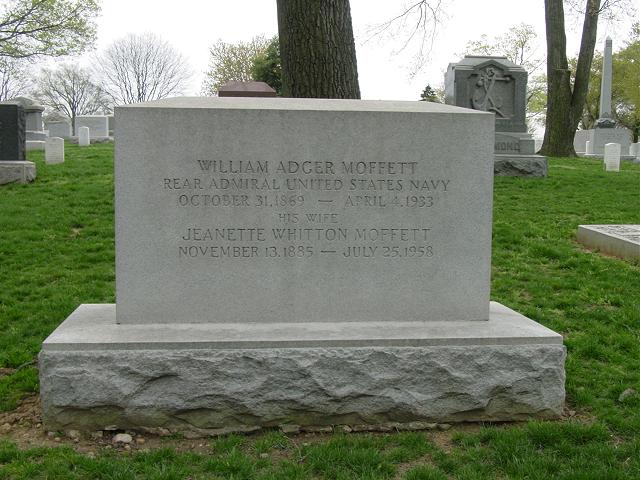

He died on April 4, 1933 in the crash of the Akron in a storm off the New Jersey coast. He was subsequently buried in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.

NOTE: His son, William Adger Moffett, Jr., Rear Admiral, United States Navy, died on 23 July 2001 and is also buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

On April 3, 1933 the Akron, under command of Commander Frank McCord was off the cost of New Jersey, fighting its was through a thunder storm. Because of the winds, heavy cloud cover and ground fog the navigator was unable to determine their drift rate and could therefore not approximate how far off their course they really were.

The weather reports from the wireless radio told of low pressure over Washington D.C. and this was mistakenly assumed to be the center of the storm. In reality, the storm that the ill-fated ship was flying through was actually an entire storm front and one of the worst that the New Jersey coast had seen in years.

The Captain decided to turn back to shore but apon arrival of the coast no break in the storm could be seen. The order was given to head back out to sea and simply ride out the weather. After several hours the Akron found some calm air. Even though the storm could be seen flashing all around, it looked as though everything was going to turn out all right. This was no doubt a relief to the ship’s Captain.

On board were two very important men, Rear Admiral William Moffett, Chief of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, and Commander Fred Thomas Berry, Commander of the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, and he was hoping to impress them with his ability to command an airship.

At a quarter past midnight the Akron was rocked by a horrific blow. The calm that the unfortunate air ship had felt was in fact the eye of the storm system. As it emerged from the other side of the eye, fierce winds caused the massive airship to buck wildly. Suddenly the ship hit an enormous downdraft and was sucked down almost a thousand feet. Only by dropping most of the water ballast and full power to the engines could the decent be stopped. The Akron was able to gain altitude briefly but was pushed down again and again until finally the force of the storm started to rip the ship apart.

With loss of control of the fins the Akron smashed into the freezing water of the Atlantic. Because the Akron carried no life vests and there hadn’t been enough time to lower her one life raft, seventy two of her seventy six man crew drowned, including Rear Admiral Moffett and Commander Berry.

The tragic end of the Akron shocked the world and the U.S. NAVY. In this one crash, the airship had lost much of its support in the military and civilian world. The death of the Macon on February 12 ,1935 would be once again due to high winds but not only. This time structural integrity would be its failing as well. After a day of military simulations with other navy sea ships, the Macon had run into a viscous wind storm.

As the captain of the ship tried to control his ship in the thrashing winds, a solid blow hit the upper fin of the ship and ripped it from its mounts. To save weight, the Macon’s fins had been attached to only two main rings instead of three as had been done in the past. This savings in weight cost the ship her life. As helium poured out of her torn rear cells, the Macon dropped all water ballast she could in an attempt to maintain altitude. The Ship immediately rocketed skyward out of control and soon had exceeded her pressure height. Helium screamed out of her emergency valves in an automated attempt to keep them from exploding form the change in pressure.

Soon the ship, with much of its helium gone, spiraled into the ocean below. Luckily, the Navy had learned from the disaster of the Akron , and the Macon carried a full compliment of life vests and inflatable rafts. Because of this, all but two of the eighty-three man crew survived. The trust of the American public in rigid airships however, did not.

MOFFETT, WILLIAM A.

Rank and organization: Commander, U.S. Navy. Entered service at: Charleston, S.C. Born: 31 October 1869, Charleston, South Carolina. G.O. No.: 177, 4 December 1915. Other Navy award: Distinguished Service Medal.

Citation:

For distinguished conduct in battle, engagements of Vera Cruz, 21 and 22 April 1914. Comdr. Moffett brought his ship into the inner harbor during the nights of the 21st and 22d without the assistance of a pilot or navigational lights, and was in a position on the morning of the 22d to use his guns at a critical time with telling effect. His skill in mooring his ship at night was especially noticeable. He placed her nearest to the enemy and did most of the firing and received most of the hits.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard